15 Notorious Medieval Knights Who Broke the Code of Chivalry

The romantic image of the medieval knight is one of honor, loyalty, and chivalry. Tales of legendary knights who defended the weak, upheld justice, and fought bravely for their lord and their faith fill the pages of literature. However, there were also men in armor who became the very antithesis of what chivalry stood for. These knights betrayed their code, brandishing their swords not in defense but in pursuit of cruelty, greed, or power. They were not the paragons of virtue that tales would make them out to be but instead left behind a legacy of treachery and violence.

Let’s take a look at some of the real villains in the age of chivalry- notorious medieval knights. From Gilles de Rais, a knight who started his career as a hero fighting alongside Joan of Arc but descended into madness and murder, to Reynald of Châtillon, whose bloody campaigns in the Holy Land earned him the wrath of Saladin, these men were all power-hungry tyrants. Their stories serve as a stark reminder that beneath the shining armor, these were men whose personal failings all too often shaped the course of history.

15 Notorious Medieval Knights Who Broke the Code of Chivalry

Gilles de Rais (1405–1440)

Gilles de Rais was a French war hero and the friend of Joan of Arc. A wealthy nobleman, Rais excelled on the battlefield during the Hundred Years’ War and was a national hero in his prime. He had been at the forefront of France’s darkest hour and fought bravely to keep the country united. But when the war was over, his riches faded, and he began to behave as a monster. As his veneer of nobility was slowly stripped away, Rais became one of the most dishonored knights in medieval Europe.

During peacetime, Gilles engaged in debauchery. He staged theatrical spectacles and squandered his fortune, living in luxury until he was bankrupt. Rumors of more sinister misdeeds began to circulate: alchemy, black magic, ritual human sacrifice, and the murder of children. By the late 1430s, complaints had reached local authorities.

In 1440, Gilles de Rais was arrested. Eyewitnesses and co-conspirators testified that Rais had kidnapped, sodomized, tortured, and murdered untold numbers of children. The details are gruesome, even by medieval standards, and are recorded in the chronicles of the time.

However, some modern historians dispute the extent of Gilles’s crimes. Others even go so far as to allege that he was falsely accused of these crimes as a way to take his land. Gilles was convicted of heresy, sodomy, and murder and hanged, drawn, and quartered.

Reynald of Châtillon (c. 1125–1187)

Reynald of Châtillon was a French knight who journeyed to the Holy Land in the Second Crusade and gained a reputation as an unscrupulous warmonger. He eventually became the Prince of Antioch through marriage, but ruled with an iron fist and was said to be cruel and arrogant. The chroniclers noted how he once had the Patriarch of Antioch dragged through the streets for refusing to finance one of his military campaigns. Even the other Crusaders were appalled by this, and it showed how little respect Reynald had for the code of chivalry.

He would continue to behave brutally and provocatively once he became a lord in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Reynald would repeatedly violate truces with Muslim leaders by attacking caravans and disrupting trade routes, sometimes even when they were carrying pilgrims to Mecca. These raids earned him great wealth, but also undermined fragile peace treaties. The chronicler William of Tyre described Reynald as a reckless and thuggish figure whose greed threatened the whole Crusader kingdom.

In 1187, Reynald’s raids would finally bring retribution from the Muslim leader Saladin, who declared a full-scale war on the Crusaders as a result. After being defeated at the Battle of Hattin, Reynald was captured and paraded before Saladin. Rather than being given a chance to redeem himself, he was executed on the spot by being beheaded at the command of Saladin, who is said to have taken a personal interest in killing him due to his history of treachery. His death was seen as poetic justice for a man who had brought so much suffering and betrayal over the years.

Reynald of Châtillon’s life is a cautionary tale of how the ambitions of one knight could lead to the downfall of many. He was anything but a chivalrous figure; he was greedy, violent, and shamelessly defiant. His actions helped set in motion the eventual fall of the Crusader states and left a legacy of infamy rather than glory.

Ulrich von Hutten (1488–1523)

Ulrich von Hutten was a German knight, humanist, and writer whose life and career exemplify the shifting worlds of the late medieval and early modern eras. Educated as a man of letters, he wielded the sword as easily as the pen. He was known for his hot temper, biting satires, and bellicose attacks on papal and imperial interference in German affairs. Hutten was far from the ideal of the courteous knight. He was a rabble-rouser, a controversialist, and a swordsman who died not in a glorious field of honor but in a noisome inn bed in poverty and ill health.

Hutten became an ardent supporter of the Reformer Martin Luther and used his pen to excoriate the abuses of the Catholic Church. He took up arms in support of Luther and the Saxon elector against their spiritual and temporal foes. Hutten joined Franz von Sickingen’s “Knights’ Revolt” of 1522–1523. It was an uprising of German nobles against bishops and princes. The revolt was ostensibly undertaken to defend reform and the traditional privileges of knights, but it quickly degenerated into marauding and bloodshed.

Ulrich von Hutten was no ideal knight, but a renegade who died in exile. Instead, his involvement in both uprisings branded him a revolutionary and a traitor to the old order of Christendom. His books were placed on the church’s index of banned works, he was put under arrest by the emperor, and he spent much of his last years on the run through Germany and Switzerland as a hunted outlaw. He died of illness and malnutrition in 1523, his once-promising career in ruins. Hutten’s life was not an example of the stability of knightly honor and faith. It was the opposite, a portrait of a world in chaos and the implosion of the old order.

Ulrich von Hutten’s swordsmanship may have been real, and he was lionized in his time and later as a forerunner of the Reformation. Nevertheless, he broke the medieval ideal of knighthood as the defense of Christian peace and unity. His swordsmanship, along with his rebellion, violence, and polemics, align him with those who perverted chivalry and knighthood not for glory but for selfish and ideological warfare.

Robert Guiscard (1015–1085)

Robert Guiscard was a Norman knight from the Hauteville dynasty who built a reputation as a pirate, mercenary, and a ruthless power-grabber in southern Italy and the Mediterranean Sea. Nicknamed Guiscard, “the cunning”, he started as a minor adventurer, but ended up as the Duke of Apulia and Calabria. His path to power, however, was less characterized by knightly honor and more by bloody opportunism. Chroniclers of the time were quick to point out his tendency to switch sides every time an ally grew too weak, even to the point of betraying the papacy when it suited his purposes.

Guiscard’s campaigns against Lombards, Byzantines, and Muslims were both brilliant and notorious for their barbarism. He sacked and plundered towns, burned and razed villages, and used large numbers of mercenaries to build his mercenary armies. He is rightfully celebrated as a military genius, but he was no standard-bearer of knightly honor and left a trail of blood and misery in his wake. The Byzantine princess and historian Anna Komnene called him a “most cunning man, a fox by nature,” and the appellation was well deserved.

Robert Guiscard even extended his habit of betrayal to the papacy, at times fighting under the pope’s banner and at others sacking Rome in 1084, reducing the city to ashes and looting it with his Norman army. The sacrilege sent shockwaves throughout Europe, revealing Robert Guiscard’s utter disdain for the knightly codes of chivalry and Christian behavior when they interfered with his goals of conquest and expansion. His victories in war did much to expand the Norman presence in Italy, but not without a considerable moral price.

Robert Guiscard’s legacy is mixed; he is to be both admired and remembered with infamy. He was one of the first Norman warlords to build a small kingdom in the southern regions of Italy and Sicily. He laid the foundation on which later prosperous Norman leaders could build, but he achieved this through deception, broken oaths, and violence. In the eyes of many of his contemporaries, he was less a knight than a warlord.

Guy de Lusignan (c. 1150–1194)

Guy de Lusignan was a French knight of low birth who became the King of Jerusalem through marriage, not military prowess. In 1180, he married Sibylla, the sister of the reigning Baldwin IV. Guy’s rise to power was controversial from the start, as many saw him as a weak and unworthy leader. Chroniclers like William of Tyre criticized him for being inexperienced and rash, hardly the qualities needed to rule a kingdom in a state of perpetual war with Saladin.

The moment Baldwin IV died and Sibylla ascended to the throne, Guy became King of Jerusalem. His reign was a disaster, as he bungled and divided the kingdom at a time when it needed unity. He chose to lead the Crusader army in person, against the counsel of his seasoned generals. He faced Saladin’s army at Hattin in 1187, and the result was a total rout: the Crusaders were massacred, the True Cross was lost, and Jerusalem fell to Saladin just a few months later.

Guy’s incompetence did not only cost the kingdom its capital, but also its reputation as a credible power in the region. He refused to give up his title even after many of his barons abandoned him, prolonging the divisions among the Crusader states. His stubbornness was not due to any strategic vision, but rather to personal pride and a thirst for power. He managed to acquire Cyprus later in his life, but he never regained his reputation as a knight.

Guy de Lusignan is often remembered not as a warrior, but as a warning. His career shows how ambition, foolishness, and lack of tact can pervert the ideals of chivalry. Instead of defending Christendom with honor, he was one of the main architects of one of the most humiliating defeats in Crusader history.

Eustace the Monk (1170–1217)

Eustace the Monk was born into a monastery in northern France. However, he broke his vows and began a life that was the antithesis of piety. He became a knight first in the service of the Count of Boulogne. He earned a reputation as a trickster and a turncoat. Contemporary chroniclers wrote that he would frequently change sides to best serve his own interests. He also conducted his life of crime both on land and at sea.

By the early 13th century, Eustace was well known as a pirate in the English Channel. He sold his services to both England and France, who were constantly in competition with each other. He would serve King John of England, or at other times the French crown, depending on who would pay more. He raided coastal towns, and his men would board merchant vessels to loot their goods, caring little about the rules of honor for men of chivalry.

He met his end during the Battle of Sandwich in 1217. The English fleet ambushed and decisively defeated the French forces under his command. Eustace was captured alive. He was shown no quarter. According to chroniclers, he pleaded with his English captors to spare him in exchange for a ransom. However, they instead struck off his head on the deck of his own vessel, much to the approval of the other English knights. He was anathema to even his fellow knights, who responded to his betrayal of his vows and his lord with violence and contempt.

Eustace the Monk serves as one of the most well-known examples of a knight who turned his back on all of the tenets of chivalry. A monk, a mercenary, a pirate, he demonstrates how easily the concepts of fealty and honor could be thrown aside in the ruthless quest for power and riches.

Sir John Hawkwood (1320–1394)

Sir John Hawkwood was an English knight who amassed a considerable fortune by selling his sword to the highest bidder, rather than serving a king or a country. Having served in the Hundred Years’ War, he crossed the Alps and entered the service of various city-states in Italy, eventually rising to command the notorious mercenary army known as the White Company. Renowned for their discipline and ruthless efficiency, Hawkwood’s forces were feared throughout the peninsula, with many towns offering him tribute simply to leave them in peace.

While he was admired for his military acumen, Hawkwood was not often seen as chivalrous. Loyal only to gold, he fought for Florence, Milan, and the Papacy at different times, frequently switching sides as contracts expired or better offers came along. Chroniclers accused him of extortion, as cities were forced to pay exorbitant fees or face his wrath. His campaigns often resulted in scorched fields and abandoned villages.

Nonetheless, Hawkwood became a celebrated figure in Italy. The Florentines eventually managed to secure his services, showering him with wealth, land, and honors in return for his protection. However, this arrangement too was based on pragmatism rather than any admiration for his knightly behavior. To his contemporaries, Hawkwood represented both the potential and the corruption of the mercenary trade: a knight who held immense power but was devoid of any loyalty or honor.

Hawkwood’s career demonstrates how far removed the medieval knight could become from the chivalric ideal. Rather than defending the weak or serving a cause greater than himself, he turned warfare into a business. Remembered as both a military genius and a mercenary predator, Hawkwood’s legacy is one of pragmatism over principle, where the sword was often more faithful to coin than to any vow.

Fulk III Nerra (970–1040)

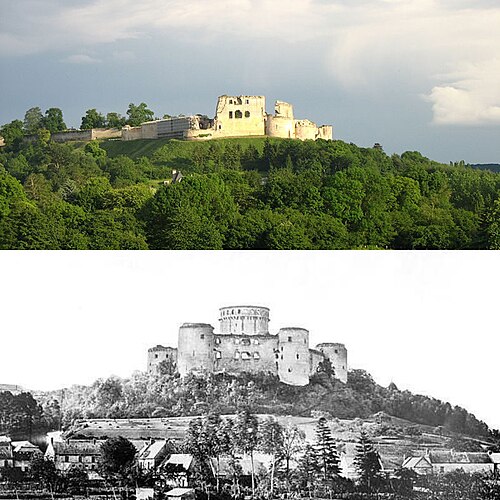

Fulk III Nerra, the Count of Anjou, was a powerful knight in the early medieval era. He is also considered one of the most cruel knights of this period. His epithet, “the Black,” was well-earned. Fulk ravaged his neighbors for decades, first Brittany, then Blois, waging nearly constant warfare to increase his power and prestige.

Fulk was a hated figure according to many chronicles. He had no qualms of burning entire villages, even churches, in order to break the resistance of his opponents. For a knight, both the safety of the people and the protection of churches were expected to be sacred.

Fulk III was a highly effective and efficient military leader. He built dozens of castles throughout Anjou to hold his newly conquered territory, but his enemies had to pay a terrible price. One chronicler claims that Fulk had a rebellious nobleman roasted alive on a spit. On other occasions, he simply had the men of a town beheaded in order to terrify his opponents.

A man who would personally kill his enemies with such savagery was not the noble, protective ideal of a knight for those who were on the receiving end of his ire. Fulk III was almost paradoxically pious as well; he would later make three pilgrimages to Jerusalem to atone for his sins.

A man of such violence seeking to atone for his sin seems an almost comical contradiction, but this is exactly what many chroniclers of the day recorded. Fulk III remains a prime example of a time in which chivalry was often not followed.

Enguerrand de Coucy VII (1340–1397)

Coucy VII, also known as Enguerrand de Coucy VII, was one of the richest and most influential French knights of the fourteenth century. He was known for his impressive collection of lands and estates, as well as his formidable fortress of Coucy. However, Coucy was not a paragon of virtue or a champion of justice. In fact, he was quite the opposite. Chroniclers of the time describe him as a greedy and oppressive lord who exploited his peasants and overtaxed his subjects. He was also known for his cruelty towards those who dared to oppose him, earning him a reputation as a tyrant among his neighbors and rivals.

Coucy VII also had a checkered history when it came to his military service. He fought on both sides of the Hundred Years’ War, serving both the French and the English at different times. This opportunistic behavior earned him the reputation of a mercenary and a turncoat. He was more interested in maintaining his power and influence than in serving the interests of either side, which may have been beneficial for his own estates but did little to enhance his honor or reputation.

Coucy’s military campaigns were also marked by a certain degree of brutality and violence. He was known for leading raids into enemy territory, sacking villages and burning crops as he went. The suffering of the common people was of little concern to him, and his actions were often more about personal gain and aggrandizement than any broader strategic objectives. In this sense, Coucy VII can be seen as an example of the darker side of chivalry and knightly warfare, where power and wealth were valued above all else.

In conclusion, Coucy VII may have been a respected and influential nobleman and lord, but his legacy is not one of honor or chivalry. Instead, his life and actions show how ambition, greed, and cruelty can tarnish the reputation of even the most powerful of knights.

André de Chauvigny (12th century)

A French knight of Poitevin descent, André de Chauvigny became prominent in the Crusades. By marrying a member of the Plantagenet family and acquiring vast estates, he secured a reputation as a wealthy and influential lord. While he adopted the veneer of a noble crusader, his actions frequently contradicted the chivalric ideals of loyalty and honor that knights aspired to uphold. Many of his contemporaries and chroniclers criticized him as a mere opportunist, willing to betray his own allies if it furthered his interests.

Chauvigny’s reputation in the Holy Land is even more notorious. He was often accused of excessive cruelty toward both his enemies and towards civilian populations. This, while a relatively common occurrence during the Crusades, was still far outside the bounds of the unwritten rules knights agreed to among themselves. He often took advantage of negotiated truces with his rivals to pillage their land and make a profit, undermining the noble ideal of defending Christendom against its enemies.

In Europe, his reputation as an opportunist and switcher of sides in regional power struggles made him a man of suspicion. His willingness to side with the party that would make him more powerful the fastest marked him as a man more interested in power than in upholding the feudal order. He was feared and admired as a warrior, but left a reputation as a schemer and opportunist.

André de Chauvigny’s life and actions exemplify some of the hypocrisy that riddled the knightly class in the Crusading era. While his life was characterized by the very excesses he later would have been celebrated for, André de Chauvigny was one of the more visible examples of crusaders who placed ambition and greed before chivalry. He was less a shining example of what a noble crusader was supposed to be than an example of the other side of the coin.

William de la Pole (1396–1450)

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, was born into a family of knightly servants during the Hundred Years’ War. He went on to become one of the most powerful figures in late medieval England during the reign of Henry VI, becoming a political figure in his later life after a career as a soldier. By then a baron and an earl, the duke was among the first to be accused of exploiting his influence over the young king.

Chroniclers accused him of corruption, mismanagement, and putting personal interests before the security of the kingdom, not, as was expected of knights, of upholding the dignity of the royal office. His actions, particularly during his fall from grace, earned him the reputation of being less a knight than a betrayer of the entire country of England for his own ends.

The Duke of Suffolk’s main point of contention was with his involvement in diplomatic negotiations with France. His arrangement of the marriage between Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou was marred by the cession of the rich French county of Maine. To his detractors, this was high treason. Added to a litany of poor military campaigns in France, which were humiliating defeats for England, this move drew ire from the nobility and commoners alike, all of whom thought that he had subverted the cause of England in the war against France.

Anger against the duke reached its peak in the late 1440s. He was impeached in parliament and accused of treason, extortion, and the embezzlement of wealth for his own use. Although Henry VI protected him, William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, was forced into exile in 1450. He never reached the Continent: on his way across the English Channel, he was intercepted by a group of sailors who beheaded him before throwing his headless body overboard to wash up on the shore. The end of William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, was as bloody and tragic as his time as a statesman had been to the people of late medieval England.

William de la Pole was a prime example of a knightly class so ravenous in their appetite for wealth and power that it corrupted the knightly ethos of service and honor. He was more or less forgotten as a statesman and quickly became among the most hated figures of the late medieval period. His downfall was an indicator of the volatility of the times, which would soon explode into the Wars of the Roses.

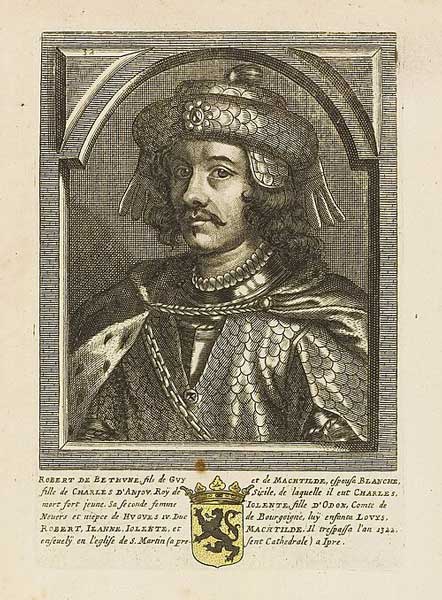

Robert de Béthune (13th century)

Robert de Béthune was a 13th-century Flemish knight who became infamous for his role in the long and bitter wars between Flanders and France. He was born into a noble family and rose to prominence through his military service. However, far from being a noble knight fighting for his kingdom, he became notorious for his treatment of civilians during his campaigns. Chroniclers reported that his troops were known for pillaging towns and villages, terrorizing the population, and carrying out acts of violence that were at odds with the chivalric ideals of protecting the weak.

In his conflicts with the French crown, Robert’s actions were brutal and opportunistic. He imposed heavy taxes on those who fell under his control and authorized raids that devastated farmland and left families destitute. His reputation was not only marred by the enemies of Flanders but also by those within his own realm who suffered under his rule. His conduct mirrored the realities of feudal warfare, where ambition and power often overshadowed any sense of justice or compassion.

Robert de Béthune is remembered as a capable warrior and a shrewd strategist, but his legacy is marred by the suffering he caused. His use of intimidation and brutality may have secured short-term victories, but it also left a legacy of resentment and animosity. Far from being a protector of Christendom, he was a knight who used his power to dominate and exploit. Robert’s career is another reminder that beneath the pomp and ceremony of knighthood, cruelty and exploitation were all too common.

Thomas de Marle (c. 1070–1130)

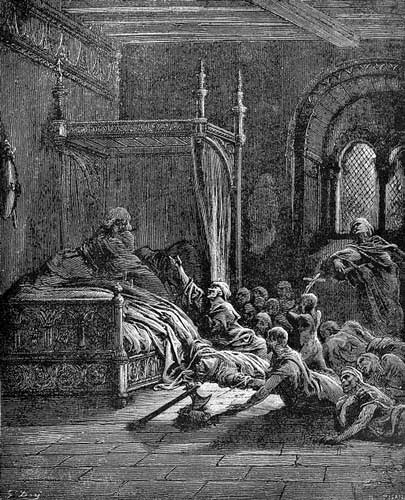

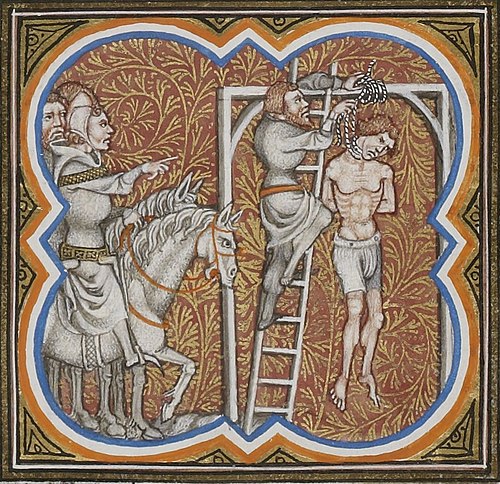

Hanging of the supporters of Thomas de Marle, Lord of Coucy, following their revolt against King Louis VI the Fat. Illumination from the Great Chronicles of France, circa 1375-1380. Paris, National Library of France, Manuscripts Department, French 2813, folio 200 recto.

Thomas de Marle, Lord of Coucy, was one of the most notorious knights in 12th-century northern France. He was the opposite of a knight protector. He was a brigand lord, and he pillaged the countryside. Chroniclers of the time accused him of robbing travelers, holding hostages, and ransoming merchants and peasants.

His castle was not a place of justice, but a den of thieves. Thomas did not protect the weak, he exploited them. He was known for his harsh punishments against those who dared to defy him. Rumors of his cruelty towards his captives were widespread. His actions were condemned by both secular and ecclesiastical authorities, who saw him as a violator of the knightly code.

Knights were supposed to be Christian soldiers, sworn to protect the innocent and serve their lord with loyalty and valor. But Thomas showed the other face of knighthood. He was a predator who preyed on the defenseless. His violence eventually led him into open conflict with his neighbors and the king. Campaigns were launched against him, but his castle and his hired mercenaries allowed him to hold out for years.

He was eventually killed around 1130, which ended his campaign of terror. Even in his own time, his name was a byword for infamy, a cautionary tale of what could happen when a lord was left unchecked. Thomas de Marle’s legacy is a perfect example of what a knight should not be. He turned knighthood into something more akin to organized banditry.

Sir Hugh le Despenser (1286–1326)

Sir Hugh le Despenser the Younger was a favorite of King Edward II. He used his influence and position for personal gain, earning the ire of many. Rising to prominence through marriage to Eleanor de Clare, granddaughter of Edward I, he amassed lands and titles. Despenser exploited his position, seizing estates, disinheritances, and wealth. Chroniclers depicted him as avaricious and violent, exploiting both friends and enemies alike.

His actions and treatment of the English nobility generated great resentment. He extorted wealth from powerful barons, manipulated justice, and even encroached on the lands of Edward II’s queen, Isabella. Despenser’s abuses threatened the stability of the realm, violating the chivalric duty to maintain harmony. Many viewed Despenser not as a knightly protector but as a predatory opportunist.

Resistance and rebellion were inevitable. In 1326, Edward II’s queen, Isabella, invaded England with her lover Roger Mortimer to depose the king. Despenser fled with Edward but was captured soon after. Tried for treason, theft, and a litany of offenses, he was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. His execution was gruesomely theatrical, a reflection of the rage against his abuses.

Sir Hugh le Despenser’s career exemplifies the corruptive potential of ambition and greed. Instead of defending the weak and serving honorably, he sought power at the expense of justice and loyalty. Remembered as one of the most hated men of Edward II’s reign, his life stands as a cautionary tale of knighthood perverted into tyranny.

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, “El Cid” (1043–1099)

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, the Cid, was a Spanish national hero and the paragon of chivalry. However, this idealized image should not obscure some harsh truths. Rodrigo was a military commander who defied the codes of knighthood, and his behavior often contradicted the values of loyalty and honor associated with medieval chivalry. Born into the Castilian aristocracy, Rodrigo began his career serving King Sancho II and then Alfonso VI. The chronicles condemn his lack of loyalty, accusing him of readily changing sides.

Banished by Alfonso VI, Rodrigo went into exile and offered his military skills to Muslim princes of al-Andalus, fighting alongside them against Christians. For Rodrigo, these alliances were a means to amass wealth and power, demonstrating a pragmatism that was not uncommon in the shifting allegiances of 11th-century Spain. However, they were at odds with the ideal of a knight whose primary duty was to serve his lord.

Rodrigo went on to establish his own principality in Valencia, where he ruled as a semi-independent warlord, waging campaigns of conquest and pillage. His campaigns, while militarily successful, were characterized by a ruthless pragmatism and opportunistic alliances with both Christian and Muslim powers. While he was admired for his military prowess, his actions often prioritized personal ambition over the chivalric ideals of Christian knighthood.

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar is remembered in the chronicles as a skilled and courageous warrior, but one whose shifting loyalties and pragmatic alliances were viewed with suspicion.

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, the Cid, would come to be venerated in later centuries as the personification of Spanish unity and the ideals of chivalry. However, in life, he was a more contradictory figure. A knight who was brave and militarily adept, but also self-serving and politically opportunistic, Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar is a reminder that the reality of medieval knighthood often fell short of its own lofty ideals.

The tales of these notorious medieval knights reveal that the age of chivalry was as much myth as reality. For every story of noble service and loyal devotion, there were men like Gilles de Rais, Reynald of Châtillon, or Hugh le Despenser, who twisted their power toward cruelty, greed, or treachery. Their lives remind us that the knightly code was often more aspirational than practiced, and that the line between hero and villain could be perilously thin.

By examining these figures, we see that medieval knighthood was far from a uniform path of honor. Some knights betrayed their lords, preyed on the weak, or sought only wealth and glory. Their legacies, steeped in infamy, serve as cautionary tales of how ambition and brutality often outweighed the virtues of loyalty and justice.