15 of History’s Biggest Betrayals

Throughout history, betrayal has been one of the most devastating forces shaping nations, wars, and personal destinies. From whispered conspiracies in royal courts to military officers switching sides on the battlefield, acts of treachery have toppled empires and rewritten the course of history. Julius Caesar’s fateful cry, “Et tu, Brute?” as he fell under the daggers of his allies in 44 BC, still echoes as a symbol of ultimate political backstabbing. Betrayals like these remind us that trust, once broken, can change the fate of entire civilizations.

The stories of history’s greatest betrayals are not merely tales of treason; they are windows into ambition, fear, and the fragile bonds of loyalty. Figures like Benedict Arnold, once hailed as a hero before turning against the American cause, or Kim Philby, whose decades as a double agent compromised countless operations, show how betrayal often carries consequences far beyond the moment of treachery. These infamous acts reveal both the high cost of broken trust and the enduring human struggle between loyalty and self-interest.

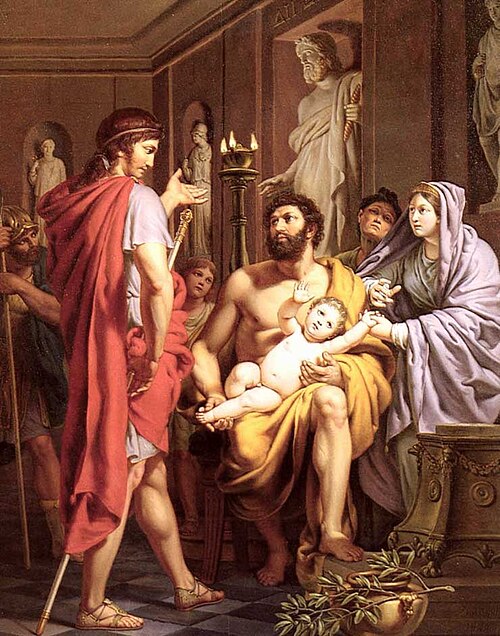

Julius Caesar and Brutus (44 BC)

Marcus Junius Brutus was a close friend and ally of Julius Caesar. In 44 BC, Brutus betrayed Caesar by conspiring with other senators to murder him. The motivations behind Brutus’ betrayal were complex and rooted in both personal and political factors. Many senators, including Brutus, were concerned about Caesar’s growing power and influence and his recent appointment as “dictator for life.” They feared that Caesar’s rule would spell the end of the Roman Republic.

Brutus, who was born into a family with connections to the Republic’s founders, was also convinced by political rivals that he must kill Caesar to preserve the Republic’s ideals. Despite Caesar’s trust and support, Brutus ultimately turned on him for what he believed was the greater good.

The image of Brutus stabbing Caesar on the Ides of March, surrounded by other assassins, is one of history’s most iconic betrayals. The ancient writer Suetonius recorded Caesar’s famous last words: “Et tu, Brute?” as Brutus and the other conspirators assassinated him. This moment captured the deep sense of personal betrayal that Caesar must have felt as a friend and former ally murdered him. The political and social ramifications of Caesar’s assassination were profound. Instead of restoring the Republic, it plunged Rome into a series of civil wars and led to the rise of the Roman Empire under Augustus Caesar. Brutus’s betrayal, meant to preserve the Republic, ultimately hastened its end.

Benedict Arnold (1780)

Benedict Arnold began the Revolutionary War as a celebrated and audacious military leader. He was instrumental in the American triumph at Saratoga in 1777. However, Arnold faced accusations of greed from political adversaries and was reprimanded rather than rewarded for his efforts. Personal financial difficulties and resentment over being overlooked for advancement contributed to his growing disillusionment. By 1779, he began corresponding with the British, believing his contributions had been unrecognized and unrewarded.

Arnold’s treason materialized when he was given command of the West Point fortress on the Hudson River. He made arrangements to hand over the fort to the British in return for a bribe and a commission as a general. His co-conspirator, Major John André, was apprehended with documents that revealed the plan. Arnold managed to escape and returned to the British side, but his reputation as a hero was irrevocably tarnished.

Arnold’s defection sent shockwaves through the colonies and highlighted the precarious nature of trust in the Revolutionary War. George Washington, who had been a supporter of Arnold, lamented, “Whom can we trust now?” The plot against West Point was foiled, but the event illustrated the vulnerability of the Patriot cause. Arnold continued to serve the British, but in America, his name became emblematic of treason. His betrayal did not alter the course of the war, but it intensified the determination of the American cause and remains one of the most infamous acts of political and military treachery in history.

Ephialtes of Trachis (480 BC)

The 480 BC Battle of Thermopylae is primarily associated with the heroic stand of King Leonidas and his Spartans against the invading Persian army of Xerxes I. However, the Phalanx of 300 Spartans and their 7000-strong army did not meet their end at the hands of the Persian forces but were betrayed by a local man. Ephialtes of Trachis showed the Persians a mountain path around the narrow pass where the Greeks had been resisting and was therefore, ultimately, responsible for the defeat of the Greeks. The precise motivation of Ephialtes’ betrayal is still debated, with the ancient sources ascribing it either to a personal grudge or the hope of reward from Xerxes.

Ancient Greek historian Herodotus’ account of the battle is the main source of information about the event, though he wrote it many years after it happened. On his account, when Leonidas received word of the path, he dismissed most of his allies and stayed with his Spartans, and 400 Thespians and Thebans to guard the rear at the pass. Leonidas’ decision allowed his Greek allies to escape, and his Spartan army died fighting to the last man, their action becoming a legend.

Ephialtes was thus responsible for the Persian victory. In the years following, Herodotus described his betrayal of the Greeks as infamous. Ephialtes’ name in antiquity was hence associated with treachery, and “Ephialtes” in Greek soon after came to mean “nightmare”.

Thermopylae, despite being a defeat, was used as a call to arms by Greek forces in later battles, and as such was critical in the Greek victory at the Battle of Salamis and Plataea. Ephialtes’ betrayal of his countrymen overshadowed all else, and as a result, he is remembered only as a traitor.

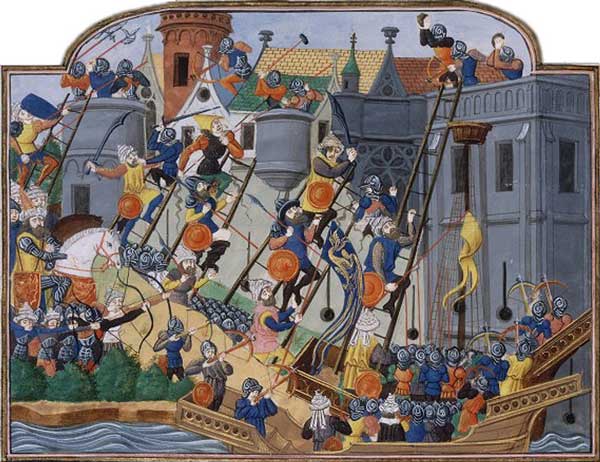

The Fall of Constantinople and the Genoese Defection (1453)

By 1453, the Byzantine Empire had shrunk to the city of Constantinople and its immediate surroundings. The Ottomans had been besieging the city for months, under the leadership of their Sultan Mehmed II. Inside the city walls, the Byzantines numbered only a few thousand soldiers and relied on foreign aid for support. Their allies included a number of Genoese mercenaries who were stationed at the walls. However, there was tension between the Byzantines and their allies, who had often been distrusted and even mistreated. The constant bombardment had taken its toll on morale, and the defenders knew they were running out of time.

On the night of the final Ottoman assault, one of the Genoese commanders reportedly left his station on the city’s walls. It is unclear if this was due to fear, exhaustion, or if he had his own agenda. In any case, his decision left a gap in the defenses that the Ottomans quickly exploited. Mehmed’s forces were able to swarm into the city through the breach, and the battle turned against the defenders. Contemporary accounts of the final assault noted the confusion among the defenders as they realized the breach, but it was too late to stem the tide. The retreat of an ally when he was needed most would spell the end for Constantinople.

The betrayal hastened the fall of Constantinople and the end of the Byzantine Empire, which had survived for more than a millennium. The conquest of the city changed the course of history by establishing Ottoman control over the eastern Mediterranean. At the same time, Europe’s land trade with Asia was now blocked, fueling the Age of Exploration. To their contemporaries, the betrayal was a symbol of the dangers of relying on foreign powers. The events of 1453 remain one of history’s most significant betrayals, where a single act of disloyalty brought down the walls of Constantinople and closed the chapter on medieval Byzantium.

Kim Philby (1960s)

Harold “Kim” Philby was a high-ranking British intelligence officer with a seemingly stellar career. Serving during WWII and the early stages of the Cold War, he gained recognition as a talented agent. However, unknown to his peers, Philby was secretly working for the Soviet Union. Recruited during the 1930s, his motivations were rooted in a combination of ideological beliefs in communism and dissatisfaction with Western politics. Philby led a double life for decades, relaying critical information to Moscow and working in significant positions within MI6, including a stint as a liaison with American intelligence.

The impact of Philby’s betrayal was immense. He compromised numerous operations, endangered agents, and damaged relations between Britain and the United States. Countless operatives exposed by Philby to Soviet intelligence were executed or imprisoned, highlighting the human cost of his espionage. Despite growing suspicions, Philby skillfully maintained his cover through connections and charm, evading consequences for years. Eventually, as evidence mounted, Philby was forced to confront his betrayal and was exposed in the early 1960s.

Philby’s subsequent defection to the Soviet Union in 1963 shocked Britain and reverberated through the Western intelligence community. His treachery intensified Cold War paranoia, straining relations between allies and sowing distrust within intelligence agencies for decades. The “Cambridge Five,” a group of British intelligence officers Philby was part of, remain emblematic of the dangers posed by ideological allegiances superseding national loyalty. Philby’s legacy as a traitor continues to be a stark reminder of the profound consequences of espionage and broken trust on global power dynamics.

Mir Jafar (1757)

Mir Jafar was an influential military commander in the rich province of Bengal, in modern-day West Bengal, India. The historical reputation of Mir Jafar was made at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Mir Jafar held a secret correspondence with the British East India Company and was dissatisfied with his leader Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah. In a bid to improve his station, he was offered the title of Nawab in exchange for his allegiance by the East India Company.

Mir Jafar was in charge of the majority of the Nawab’s troops at the start of the battle. Mir Jafar decided to not send in his troops in time. The Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daulah’s, army was easily outnumbered and on the verge of defeat. Robert Clive, a British commander and leader of the East India Company’s troops, had won the battle of Plassey, and Mir Jafar was made Nawab as was prearranged with the British. Mir Jafar held the East India Company to its word and was made Nawab of Bengal.

Mir Jafar, at once, accepted the offer and betrayed his leader in return for a better position for himself. His reasons included a desire for power and an unwillingness to be ruled by his leader Siraj ud-Daulah, who had alienated several individuals in his court and military.

Mir Jafar’s treachery came at the cost of one of the most prosperous provinces in India, Bengal, which went to the East India Company. Mir Jafar’s rule was considerably weak as he owed his station as Nawab to the British East India Company. He is remembered as a traitor in Indian history and as one of the most nefarious South Asian figures, if not the most nefarious, in the subcontinent for his actions in the battle.

He was only able to hold on to his power for a short while before he was deposed in favour of Mir Qasim. The Battle of Plassey is credited with the political power of the British in the subcontinent, which went on for almost two centuries.

Alcibiades (5th century BC)

Alcibiades was an Athenian statesman and general of exceptional talent, but also notorious for his repeated betrayals. An attractive man and a disciple of Socrates, he had rapidly advanced in the political life of his city. As an ambitious man eager to implement his daring ideas, like the Sicilian Expedition, he had made many enemies. Alcibiades was accused of profaning the mysteries of Eleusis, a sacrilegious act, right before the fleet set out on its campaign, and was recalled to stand trial. Not willing to face the certain death sentence from his fellow Athenians, he defected to Sparta.

In Sparta, Alcibiades revealed military secrets of Athens, counseling the Spartans on how to utilize their new gain of Decelea best and further cut off the food supply of Athens. His advice and intelligence were able to seriously harm his former country, ensuring that Sparta could eventually win the long war against the Athenian Empire. As his new life in Sparta became shaky, he then defected again, this time choosing to go over to the Persians and seeking their protection by advising their satraps.

Alcibiades would later return to Athens in a reconciliatory fashion, but it was too late to reverse the consequences of his actions. At the moment when the city needed his strategic mind, he had already contributed to its ruin by siding with its enemy Sparta at a decisive point in the war, ensuring Athens’ downfall and bringing about a change in the power dynamics of Greece.

Artabanus (465 BC)

Artabanus was one of the trusted officials of Xerxes I of Persia, a commander of the royal bodyguard and thus very powerful. But in 465 BC, he murdered the king in his sleep by stabbing him. A eunuch attendant allegedly helped Artabanus, and once he had killed the Great King he tried to hide the fact and retain control of the Persian court as the real power behind the throne. He was successful in the short term, using his position of authority to eliminate those who would have been his rivals. Eventually, though, his deception was discovered, Xerxes was found to have been murdered and Artabanus himself was killed by the new king Artaxerxes I.

The Persian court was thrown into confusion, with some sources suggesting that Artabanus was trying to take the throne for himself. In contrast, others hold that he was happy to have Xerxes’ son Artaxerxes I ascend to the throne but planned to control him as a puppet. Artabanus was initially successful in keeping his involvement a secret and using the confusion to stamp his authority on the empire. But eventually the news that Xerxes had been murdered was leaked, and Artaxerxes turned against him. The murdered Xerxes’ successor as King of Kings was Artaxerxes I.

The death of Xerxes and the subsequent machinations of Artabanus had several significant effects on the Persian Empire as a whole. Persia, which at the time of Xerxes’ death stretched from Greece in the west all the way to India in the east, was suddenly destabilized, and its image of an apparently divinely-sanctioned royal authority was damaged.

The legacy of Xerxes, a great builder and a bold, if ultimately unsuccessful, military leader, was to some degree overshadowed by the betrayal of a trusted member of his own court, and the intrigues which followed his death. The murder of Xerxes is one of many examples where Persian military power was more decisively affected by the activities of a single official than by foreign enemies.

Themistocles (5th century BC)

Themistocles was known as one of the most brilliant Athenian heroes of his time. During the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC, he managed to inflict an almost irreparable defeat on Xerxes I of Persia. This is how the attempted Persian invasion of Greece was finally repelled, and Themistocles became a national hero. However, these successes did not leave his detractors and rivals indifferent. In the mid-470s BC, Themistocles fell out of political favor in Athens. His fellow citizens exiled him and later accused him of treason. This forced the leader to seek asylum outside Greece.

Themistocles spent the time of exile on the road. And after a while, the best, most famous general of Athens made the most unexpected career move of his life: he betrayed Greece and went to the Persians. King Artaxerxes I of Persia, the son of Xerxes I, received Themistocles in an honorable way and was ready to use his military experience to the detriment of Athens.

Themistocles spent the time of exile on the road. And after a while, the best, most famous general of Athens made the most unexpected career move of his life: he betrayed Greece and went to the Persians. King Artaxerxes I of Persia, the son of Xerxes I, received Themistocles in an honorable way and was ready to use his military experience to the detriment of Athens.

According to the historian Plutarch, the exiled Athenian even promised the king to teach him how to deal with Greece most effectively. However, Artaxerxes I did not immediately put Themistocles’ military experience to use. However, for many Greeks, this alone was enough: a great man, who was once at the forefront of the fight for the independence of the homeland, ended up changing sides and becoming a mercenary of the hated Persians.

Pausanias of Sparta (5th century BC)

Pausanias of Sparta was a revered hero of the Persian Wars who was appointed leader of a Greek coalition army in the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC. His leadership was pivotal in securing a crucial victory for Greece and routing the Persian invaders. As a result, he was revered as a hero throughout Greece. However, Pausanias’ success went to his head. He became arrogant and began to imitate Persian customs, earning him the distrust of his fellow Spartans. He began to scheme and even conspired with the Persian Empire, in hopes of gaining more power for himself.

As recorded by the historian Thucydides, Pausanias began to negotiate with the Persians, offering to help them in exchange for money and political influence. He released Persian prisoners of war without consulting the Spartan leadership, and his overall behavior raised suspicion. He was even rumored to be plotting to overthrow the Spartan government. When the evidence of his treachery became too great to ignore, Pausanias was recalled to Sparta and put on trial.

In the end, the Spartans took decisive action against him. Pausanias was found to have sought sanctuary in a temple when his plot was discovered, and his fellow Spartans walled him in and starved him to death, as a traitor to his country. His betrayal was a reminder to all Greeks that individual ambition could threaten the collective good. While his death helped to maintain stability in Sparta, it also strained relations with the other Greek city-states and highlighted the ever-present threat of collusion with Persia. Pausanias’s story is a cautionary tale of a once-great hero brought low by his own ambition.

Vidkun Quisling (1940)

Vidkun Quisling was a Norwegian politician and former army officer who gained infamy as a collaborator with Nazi Germany during World War II. He started his career with military service and post-war relief work in Russia, and founded Norway’s fascist-inspired Nasjonal Samling party. In April 1940, as Nazi Germany invaded Norway, Quisling, whose ambitions had led him to switch sides in 1940, tried to take power by proclaiming himself as prime minister and pledging his loyalty to the German occupiers.

Quisling acted as a traitor to his own country, betraying it to the Nazis and using his power to crush resistance movements and support German policies. He earned a reputation as a Nazi collaborator and puppet, and the Norwegian people deeply resented his actions. For many ordinary Norwegians, Quisling represented the occupation and oppression they were suffering, and his name became synonymous with treason. This led to resistance against his regime becoming a central aspect of Norway’s fight during the war.

In the aftermath of the war, Quisling was arrested, tried, and executed for high treason in 1945. His actions during the war left a dark legacy, and his name is now used worldwide as a synonym for “traitor.” Quisling’s betrayal of his own country for personal and ideological reasons serves as a stark reminder of how a leader can be motivated by both opportunism and ideology to betray his people, and he remains one of the most infamous collaborators of the 20th century.

Marcus Junius Silanus (1st century AD)

Roman governors of the early empire wielded significant power and influence. Marcus Junius Silanus, a member of a distinguished family connected to Augustus, rose through the ranks with strong favor from the emperor. However, the instability that followed the reign of Tiberius created a climate of uncertainty, where governors and generals grappled with questions of loyalty. In their pursuit of power and self-preservation, these men often oscillated in their allegiances. Silanus, in particular, betrayed the trust that had been placed in him as he sought to navigate the treacherous currents of the empire.

Tacitus provides insights into the wavering loyalty of Roman governors and generals, noting their shifting allegiances during a tumultuous period. Silanus is documented to have changed sides and even joined forces with rivals during this power struggle. His betrayal was not driven by ideology but by ambition and a desire for self-preservation in Rome’s cutthroat political environment. In a system where imperial authority relied heavily on the loyalty of governors, Silanus’ disloyalty highlighted the vulnerability of centralized power. Tacitus subtly underscores how such actions contributed to a lack of confidence in Rome’s ruling elite.

Betrayal in this context had consequences that rippled throughout the empire. By prioritizing personal ambition over loyalty, Silanus and others like him exacerbated the climate of suspicion and instability that characterized the Julio-Claudian dynasty. The weakening of ties between Rome and its provinces further fueled the cycles of purges and executions that marked the early years of the empire. Silanus’ actions serve as a reminder that even within the seemingly unshakable Roman system, betrayal from within could erode the foundations of imperial rule.

Andrei Vlasov (1940s)

At the outbreak of World War II, Vlasov was a highly decorated Soviet general. He was lauded for his role in defending Moscow against the German invaders in 1941. Still, the following year he was taken prisoner by the Germans as part of a surrounded Soviet garrison at Leningrad. Vlasov had grown to despise Stalin and the Soviet regime, which he felt squandered the lives of its soldiers, and he agreed to collaborate with the Nazis and raise an anti-Soviet army out of other Soviet prisoners of war. Vlasov tried to present himself as the leader of those Soviet soldiers who wanted to turn against Stalin.

Financed and organized by the Nazi regime, Vlasov and his Russian Liberation Army of Soviet deserters fought against Stalin’s regime in the belief that he was waging a fight against Stalinism. Still, his decision to fight for the Nazis was seen as treason by most Russians at the time and has since. The Nazis never trusted Vlasov, and he was never given a great deal of autonomy in his work as a Nazi collaborator.

The Vlasov Army was primarily used as a propaganda tool and not deployed into combat situations where it could have made a significant impact. Nonetheless, the existence of Vlasov and his army allowed the Nazis to present an enemy within Soviet society, causing divisions and a drop in morale amongst prisoners of war.

Vlasov’s defection and leadership of the Russian Liberation Army backfired when the Germans surrendered in 1945. Soviet forces recaptured him, tried him for treason, and sentenced him to death by firing squad in Moscow. His name is today associated with treachery in Russia, and he remains a controversial figure to this day. Some attempt to excuse his actions by pointing out that Vlasov was fighting against Stalin, not necessarily against Russia itself, but it remains a fact that he led a movement to fight on the side of the Nazis against his own countrymen.

Count Julian of Ceuta (8th century AD)

Count Julian of Ceuta is famed for allegedly betraying the Visigoths of Iberia and opening the peninsula to Muslim invaders in 711. Julian was a Visigothic governor of North Africa who became embittered against his overlord, Roderic, the king of the Visigoths. Medieval chronicles give different reasons for Julian’s disaffection; some describe him as avenging a dishonour done to his daughter by Roderic, but others are political. In any case, his bitterness hardened into enmity, and he became an ally of the Muslim general Tariq ibn Ziyad.

Julian is alleged to have given ships to carry the Muslims over the Strait of Gibraltar, and guided them overland into Iberia. This treachery allowed Tariq to lead a successful invasion which defeated Roderic’s army at the Battle of Guadalete. The Visigothic kingdom disintegrated shortly thereafter. Julian’s betrayal made it possible for the Muslims to conquer most of Iberia in the following years, establishing the Al-Andalus period.

Later Christian writers vilified Julian as a traitor who sold out his country and his religion for personal reasons. The legendary accounts are probably a mixture of truth and fiction, but they illustrate the importance of a betrayal in opening the peninsula to an almost eight-century Muslim presence in what is now Spain and Portugal.

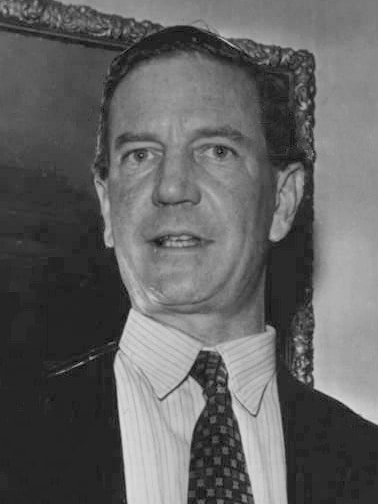

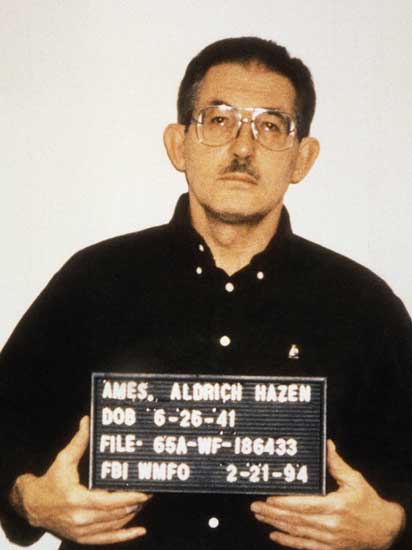

Aldrich Ames (1990s)

Aldrich Ames worked as a CIA counterintelligence officer in the 1960s, but he became dissatisfied with his job and began to suffer from financial difficulties by the mid-1980s. This led him to find a new job in 1985 when he first contacted the Soviet Union’s KGB and offered to sell them intelligence information in exchange for money. Over the next ten years, Ames provided the Soviets with over $2 million in information, which the CIA later determined compromised a large number of American assets.

The impact of Ames’ treason on the United States was devastating. He compromised the identities of a significant number of American agents in the Soviet Union, many of whom were captured and executed as a result. Furthermore, his espionage severely damaged U.S. intelligence capabilities in Moscow, essentially blinding the CIA during a critical time in the Cold War. As a result, investigations into his activities found that his actions “compromised more highly classified CIA assets than any other case in history.”

In 1994, Ames was arrested for his role as a spy after the FBI and CIA were tipped off by unusual financial transactions that he had with the Soviet Union. He was subsequently convicted and sentenced to life in prison, and his case remains a stark reminder of the potential for insider threats in intelligence work. In addition to the loss of lives, Ames’ actions had a lasting impact on trust between the CIA and its agents worldwide, and his case serves as one of the most notorious examples of espionage in history.

The Enduring Shadow of Betrayal

From Brutus striking down Caesar to Aldrich Ames betraying his country for profit, acts of treachery have repeatedly altered the course of history. Whether driven by ambition, ideology, or revenge, betrayal has toppled rulers, prolonged wars, and left nations reeling. These stories reveal that betrayal is never a private act—it carries consequences that ripple outward, shaping the destinies of empires and peoples alike.

The memory of such betrayals lingers as a stark reminder of the fragility of trust. While traitors are condemned and their names stained with infamy, their choices underscore the dangers of unchecked ambition and fractured loyalty. History’s greatest betrayals remain powerful lessons, showing how one act of disloyalty can echo across generations.