20 Female Patriots of the American Revolution

The female patriots of the American Revolution made significant contributions to the cause of independence, despite being largely unrecognized by history. These women went beyond traditional roles, serving as spies, messengers, fundraisers, and even soldiers disguised as men. They played crucial roles in supporting the Continental Army and upholding the principles of liberty during uncertain times.

From Deborah Sampson, who disguised herself as a man to fight in the army, to Mercy Otis Warren, who used her writing to influence political ideas, these patriots helped shape the foundation of a new nation. Their stories inspire and are integral to understanding the full extent of sacrifice and service during the Revolutionary War.

Deborah Sampson

Deborah Sampson is one of the most famous people of the American Revolution. Sampson was born in Massachusetts in 1760. She disguised herself as a man and enlisted in the Continental Army as Robert Shurtliff in 1782. At a time when women were not allowed to serve in the military, Sampson risked everything to become a soldier in the army of the United Colonies. She served with the 4th Massachusetts Regiment and saw active duty during the war. She was even wounded in battle, and to prevent others from knowing she was a woman, she treated her own wounds. She took a penknife and needle and removed the musket ball from her thigh, and sewed up the hole.

Eventually, she became ill and was treated in the hospital, where she was discovered. She was not punished but was honorably discharged by General Henry Knox in 1783. After the war, she became a public speaker and petitioned for a military pension, which she received, one of the few women to do so for service in the war. Sampson’s courage and fortitude helped break gender barriers and left her a place in American history.

Molly Pitcher (Mary Ludwig Hays)

Few people have achieved American Revolutionary War fame through one action than Mary Ludwig Hays. Popularly remembered as Molly Pitcher, she has become synonymous with female patriots. Legend says that on a hot day in June 1778, Mary was busy on the battlefield during the Battle of Monmouth, carrying water to the soldiers. This would earn her the nickname “Molly Pitcher.” When her husband, who had been manning an artillery piece, was overcome by heat exhaustion or an injury, Mary took his place, loading and firing the cannon with the rest of the men as bullets flew around her.

Her presence of mind and quick action both inspired the men around her and served to represent the support that women provided during the Revolutionary War on and off the battlefield. Although some of the more salacious stories about Molly Pitcher were likely embellished or outright false, her bravery was enough that the Pennsylvania government would later provide her a small pension. Molly Pitcher is an American patriot icon. Her story exemplifies the patriotism, courage, sacrifice, and strength of American women who supported the cause of independence.

Sybil Ludington

Sybil Ludington was only 16 years old when she made a midnight ride similar to the one later made by Paul Revere. On April 26, 1777, Sybil rode through Putnam County, New York, at night to warn American militia forces that the British were attacking the town of Danbury, Connecticut. She rode over 40 miles in distance – twice the distance of Revere – through rain and rugged terrain, through the night, and warned the widely dispersed colonial forces along the way.

Her efforts helped the militia gather and respond, but they were unable to save the town. The incident still made her a legend in the region, where her bravery was widely known and appreciated. It is said that General George Washington personally thanked her for her efforts, but there is no official record of such a meeting. There are several statues and memorials to her today.

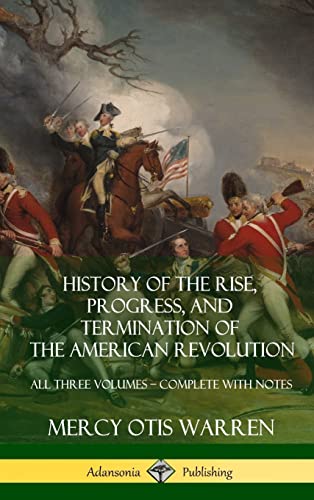

Mercy Otis Warren

Mercy Otis Warren was a keen political observer during the Revolutionary period. She was a member of a politically important Massachusetts family. She began writing political satire and drama, criticizing British authorities and praising those who resisted British control. Her plays, The Adulateur and The Group, were especially influential. The characters who were Loyal to the Crown were not only corrupt but also ridiculous in their behavior and admiration for British authority. It was rare in that period for a woman to publish a political document. Mercy’s plays were widely circulated and helped to inflame revolutionary opinions.

She also wrote political essays, and after the war, a three-volume History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution. This was one of the first histories written of the war, and was the first by a woman. It was insightful and sometimes a passionate argument in favor of liberty. Mercy Otis Warren had the strength and conviction to make her voice heard in defense of the Patriot cause.

Esther de Berdt Reed

Esther de Berdt Reed is best known for spearheading one of the most successful grassroots efforts to support the Continental Army. Born in England, the wife of American patriot Joseph Reed became a supporter of the American cause of independence. In 1780, when soldiers were suffering from shortages of the most basic supplies, Esther organized the Ladies Association of Philadelphia to help. The group of women raised over $300,000 (in today’s dollars) to purchase linen and sew over 2,000 shirts for Washington’s troops, many of whom were on the front lines, in rags, and facing dire conditions.

Esther urged women to help the cause as a patriotic duty and published an essay called “The Sentiments of an American Woman.” She was a leader, and her organizational skills gave women a public voice during wartime. Esther died of an illness that year at the age of 34, but her actions had an impact. Esther de Berdt Reed’s compassion and determination brought dignity and comfort to those on the front lines, demonstrating the power of civic action in driving a revolution.

Anna Strong

Anna Strong was a spy who belonged to a group of American spies known as the Culper Ring. The Culper Ring was an organized network of American spies in British-occupied New York during the American Revolutionary War. The spy ring’s operations were run under the direct orders of General George Washington. Anna Strong was based in the town of Setauket, Long Island.

She was responsible for signaling other spies by hanging laundry outside her home. A black petticoat and handkerchiefs were hung in specific formations on her clothesline to indicate where and when another agent should go to collect a message or deliver it to a safe location. Anna Strong would signal when British soldiers were moving from one place to another without being detected.

Her exact role is unknown as she like many other spies kept it a secret. Anna Strong was a very important factor in the success of the Culper Ring espionage tactics. She used her cover as a woman to avoid suspicion while gathering information in British-occupied land. Anna Strong’s patriotic spirit and ingenious ways helped to save lives and gave a major impact to the war’s outcome. Her service shows how even the smallest of tasks can make an important difference in the success of war efforts.

Agent 355

Agent 355 was one of the most enigmatic and fascinating figures of the American Revolution. She was a woman whose real name is unknown and was only referred to as “355” in a code in the letters of the Culper Ring. She was a Patriot spy who operated in British-occupied New York City during the war, and her intelligence is credited with uncovering the treason of Benedict Arnold and the operations of British Major John André, who was captured by the Americans in 1780.

Historians have speculated that she was a woman of high social status, which allowed her access to British officers and sensitive information. She is thought to have been captured by the British and may have died on one of their prison ships. Agent 355’s true identity is still unknown, but she is remembered as a symbol of the many anonymous women who risked their lives for the Patriot cause during the war.

Nancy Hart

A quick shot with a musket and a sharp tongue were two of Nancy Hart’s claims to fame. As a Georgia frontierswoman, she supported the Patriot cause with zeal, and she was just as comfortable in the woods as at her kitchen table. The most familiar story about Hart tells of the time she captured a band of British soldiers.

The men had stormed into her cabin and demanded a meal. Hart set to work cooking for them, but first, she quietly slipped her long rifle out of the loft above the fireplace and held them at gunpoint. She sent her youngest son for help. As the family members converged on the cabin and the soldiers were led away, one of them grabbed Hart and she shot him dead. She also wounded another soldier before they were led away.

Stories like this made Hart popular with Patriots in her area and earned her a spot in the pantheon of Georgia history. The Loyalists were not as enamored of the feisty widow. Hart’s home county, Hart County, Georgia, was named for her by the area’s residents after the war. It is the only county in Georgia named after a woman. Archaeologists later discovered a cabin site with six skeletons buried nearby. Hart County lore says that the site may be where the captured soldiers were killed.

Lydia Darragh

Lydia Darragh was a Philadelphia Quaker who saved American lives through daring during the Revolution. Quakers disapproved of any participation in war, but this did not stop Lydia from taking risks. British officers used her house for a base of operations and a meeting place in 1777. Lydia’s family was Quaker, so the officers did not suspect the quiet household of being a threat. However, Lydia risked all by hiding in a closet and listening. She overheard plans for a sneak attack on the American army near Whitemarsh, Pennsylvania.

Acting quickly, she went “purchasing flour” and past British lines to warn General Washington’s troops. Washington’s army was alert, and the British attack was thwarted. Darragh returned home, and no one knew the difference. Darragh’s story was not publicized in her lifetime. However, this act of quiet but firm resistance became legendary. Lydia Darragh’s bravery and intelligence prove that the fight for independence was not won only with guns, but also with brains.

Ann Bates

Ann Bates was a Loyalist, a supporter of the British. However, she also became a double agent. Initially working for the British, Bates later served the Americans as well. It is said that she made a habit of infiltrating American camps by disguising herself as a peddler. Peddlers were able to roam around from soldier to soldier without raising any suspicions. Bates was known for her disguises, and during her service to the Americans, she made good use of them.

Her disguises and her status as a former wife of a British artilleryman aided Bates in her role as a spy. By identifying various types of military equipment and roughly estimating troop sizes, Bates proved to be an effective informant. She is also said to have made her way into Washington’s army, stationed in White Plains, New York. Bates risked everything to continue collecting information and passing it on to the Patriots. The story of Bates’ life as a spy goes from supporting the British to changing her allegiances and working for the other side.

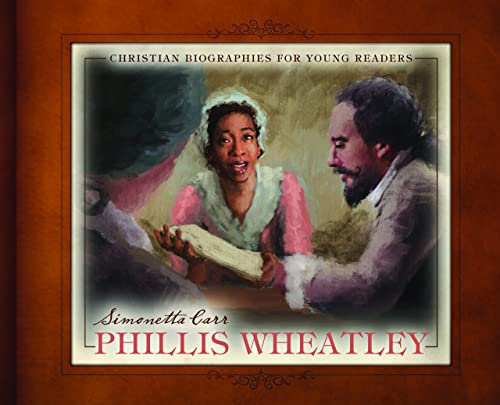

Phillis Wheatley

Enslaved African American Phillis Wheatley’s poetry expressed both the hope and the hypocrisy of the American Revolution. Captured in West Africa as a child, sold to a slaver, and brought to Boston on the crowded hold of a ship, Wheatley was purchased as a slave by the Wheatley family. Recognizing her intelligence, the Wheatleys allowed her to receive an education. By age 12, she was reading Homer, and by age 20, she had published the first book of poetry by an African American woman. Her 1773 volume, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, brought her international fame and recognition for her fierce intelligence and moral and aesthetic clarity.

In her poems, Wheatley argued for liberty, even as she called out slavery’s hypocrisy in a country fighting for freedom. She wrote a poem to General George Washington himself, for which he wrote her a note, allowing her to come meet him. A powerful testament to the Revolution’s freedom, Wheatley’s life and words changed how many people viewed the fight for liberty, while she began to clear the way for later generations of African American writers and activists.

Elizabeth “Betsy” Ross

It is said that Elizabeth “Betsy” Ross, a Philadelphia upholsterer, sewed the first American flag. The flag would become an enduring symbol of the American struggle for freedom. In 1776, according to an oral family history, she was asked by George Washington and two members of a clandestine committee of congressmen to make a flag for the Continental Army. Ross is said to have suggested replacing the six-pointed stars with five-pointed ones, as they were easier to cut and sew, and this change was accepted.

The role of Betsy Ross as flag-maker has been disputed by some historians, though she was clearly a Patriot and remained so after her husband died in an accident at his munitions mill. Ross worked her upholstery business alone after his death and supplied the army with flags, uniforms, and other supplies during the war.

Margaret Corbin

Margaret Corbin’s incredible courage was on display during the Battle of Fort Washington in 1776. She was with her husband, John Corbin, who had a cannon in the battle against the British. When John was killed, Margaret immediately took his place and manned the cannon until she was hit with grapeshot. Margaret was left disabled for life by her wounds. She left a big impression on the soldiers and military officials she met with her heroics.

Margaret became the first woman in American history to be given a military pension for her service. The Continental Congress gave her half of a male soldier’s monthly pay. They increased it in later years to cover her cost of care. Margaret lived the rest of her life in poverty, but she was not forgotten. She is now a symbol of women in combat and sacrifice.

Patience Wright

Patience Wright was an American sculptor, best known for her waxworks. A patriot spy, she spied on the British while in London. Wright was born in New Jersey. She later moved to London, where she made wax sculptures, primarily portraits of nobility. Wright rose to popularity through her work, which gave her access to influential and well-connected individuals. Patience Wright was a quiet but fervent supporter of the Patriot cause, and used her notoriety to pass along information to the patriots. Wright is said to have hidden messages in the waxworks and shipments she sent to America, and she is believed to have provided the patriots with information about British military operations.

A somewhat eccentric and garrulous woman who often shocked the British establishment with her frankness, Wright was an ardent American patriot, who railed against British injustice. Wright wrote to Benjamin Franklin, and her correspondence with other Patriots demonstrates her activism. Wright never returned to the United States after her initial trip, but her actions in London were vital to the cause, making her one of the few American women to serve overseas in a spy capacity during the war.

Martha Washington

Martha Washington made significant contributions, although often unacknowledged, to the cause of the Revolutionary War by providing support to the army during its most trying times. She accompanied her husband, General George Washington, to every winter encampment of the Continental Army and, in so doing, supported and comforted him while he led the army through the challenges of the war. During the winter of 1777–1778 at Valley Forge, she and the wives of other officers sewed clothes, knitted socks, and cooked meals for the soldiers. She brought a sense of home and normalcy to the austere conditions and deprivations of war.

In addition to these services, Martha Washington helped to organize the sending of supplies, raised through donations and fundraising efforts, to an army that was in great need. She and other women, such as Esther de Berdt Reed, utilized their abilities and connections to raise the necessary goods and funds for the effort. She had no desire for public acclaim, but through her support, she showed her steadfast commitment to the cause of liberty.

Jane McCrea

Jane McCrea was a 23-year-old woman whose death at the hands of Native Americans in 1777 became a rallying point for the Patriot cause. She was engaged to a Loyalist officer with the British General John Burgoyne’s army, which was advancing upstate New York. She was on her way to meet her fiancé near Fort Edward, NY, when Burgoyne’s Native American allies captured her. It is not known if she was killed by them or died during a struggle, but her body was found with several wounds and her scalp was missing.

The story of her death enraged American colonists, and was trumpeted by Patriot leaders as an example of British barbarity. They used it as propaganda to increase anti-British sentiment, and it did lead to more men joining the Patriot militias. Her name became a rallying cry for the Patriot forces, and although she never personally took part in the war, she was a significant influence on public opinion.

Mary Draper

Mary Draper was a Massachusetts widow who used her household to support the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. As the war interfered with daily life and shortages became common, she used her own supplies to help the men who passed through her region. Draper melted her family’s pewter dishes to create bullets for the fighting men and provided food, clothing, and blankets to the many needy soldiers that she encountered. Her patriotism was intense, and she believed that all citizens had a duty to fight for their liberty.

In addition to providing material supplies to the army, Draper allowed soldiers into her home where she provided them with hot food and a place to sleep. She did this especially during the cold winter months. She never held a weapon in battle, but her role in providing supplies and support for the war was no less important than that of the soldiers on the front lines. She encouraged her neighbors to provide for the soldiers in a similar manner. Mary Draper’s contributions are an example of the many ways women helped to support the Revolutionary War effort from home.

Catharine Littlefield Greene

Strong and capable, Catharine Littlefield Greene exemplifies the women who made the often-overlooked personal contributions during the American Revolution. The wife of General Nathanael Greene, one of George Washington’s most successful field commanders, she was at the front lines of the war effort: tending to family, managing estate, and ensuring her husband’s comfort while he was away for years at a time.

She also traveled to his encampments, offering care and company to her husband and comfort to the soldiers as they endured the long years of war. She was a popular visitor in military camps, often providing food and supplies for the troops and some measure of comfort to officers and soldiers alike. Her quick wit and intelligence made her a popular confidante of military leaders.

After the war, Catharine continued her work rebuilding the nation and is associated with another essential piece of the country’s development: the cotton gin. Although she didn’t create the gin herself, she was a necessary source of support and encouragement to Eli Whitney, the inventor, who resided at her plantation while working on his design.

While she did not fight on the battlefield, Greene made a significant difference behind the scenes during and after the war, influencing both its course and outcome, as well as shaping the postwar nation through her support of innovation. Catharine Littlefield Greene is remembered as an example of how women aided the Revolution, not only by supporting the troops but by leadership and innovation, as well.

sally St. Clair

Sally St. Clair was a woman who allegedly disguised herself as a man to fight for the Patriot cause during the Revolutionary War. Legend has it that Sally joined a regiment in South Carolina and that she kept her true identity a secret from the other soldiers. As a member of the regiment, she was able to fight alongside them in the defense of liberty. Local lore claims that she was in love with a soldier and joined the army so that she could be near him in battle.

The truth about Sally’s gender was only discovered when she died during a skirmish near Savannah. As her body was being prepared for burial, it was revealed that she had been a woman. Little is known of Sally’s life, and historians are left to debate the finer points of her existence. However, she remains an influential figure of devotion and patriotism in local lore. She is said to be representative of the many nameless women who put themselves in harm’s way for their country during a time when such acts were forgotten, mainly or left unheralded.

Prudence Cummings Wright

Prudence Cummings Wright was an outspoken, spirited Patriot who became a leader when the security of her town was at stake. In 1775, word reached Pepperell, Massachusetts, that a group of couriers was coming through with information that would aid the British troops. Prudence and a group of local women took it upon themselves to find and stop the Loyalist spies. Dressed in their husbands’ clothes and with arms from their homes, these Pepperell women, later known as the “Minutewomen of Pepperell”, set an ambush at Jewett’s Bridge, stopped the spies, and captured them and the information they were carrying. The secret dispatches were turned over to American military officials.

Wright’s militia was noteworthy because it consisted entirely of women during a time when the decision to go to war was in the hands of men. Women organized and acted quickly to protect their town, and as a result, they were able to contribute directly to American military intelligence. The provincial government reimbursed Prudence for her militia’s capture of the dispatches. Her story shows that the passion to defend freedom and the will to fight were not exclusive to any one group.

Honoring the Legacy of Female Patriots

They are bold women, intrepid women —a cross-section of brave female patriots who served the cause of American independence in various capacities during the Revolutionary War, whether as soldiers, spies, fundraisers, nurses, authors, publicists, servants, or leaders. The stories of these 20 women come from diverse backgrounds and include both well-known and lesser-known women.

Their involvement in the war and the building of our country took them far beyond the domestic duties of the day in many cases. As these stories unfold, you’ll find common threads of courage, tenacity, compassion, and perseverance that helped shape our nation and our founding ideals. These are true stories about the fundamental contributions made by American women during the Revolutionary War.

![[Video] Women of the American Revolution Part 2](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-12-at-2.54.41 PM.jpg)