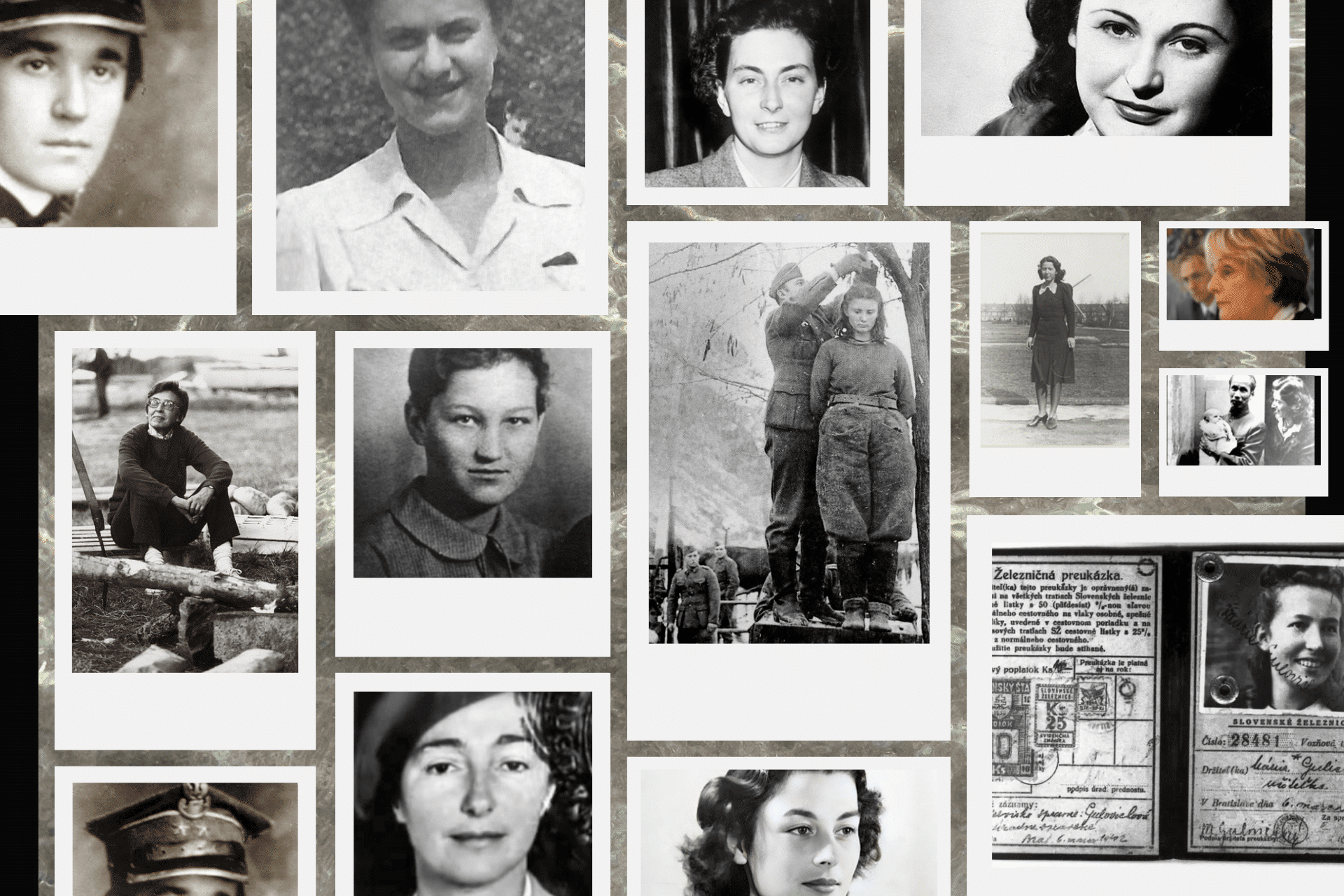

20 Female Resistance Fighters Who Took on Nazi Germany

World War II witnessed the unsung heroism of female resistance fighters who defied Nazi occupation. These courageous women, often overshadowed in historical narratives, played vital roles in espionage, sabotage, and armed resistance. Working in underground networks, they aided Allied forces, smuggled fugitives, and disrupted enemy operations.

Figures like Nancy Wake led daring missions in enemy territory, while others, such as Sophie Scholl, used words to inspire defiance. Their bravery knew no bounds, with the Gestapo hunting them relentlessly. As historian Margaret Collins Weitz aptly wrote, “Women in the Resistance were not playing at war. They fought and died for liberty.” Their stories embody the unbreakable spirit of the female resistance fighters who stood against oppression.

Nancy Wake (New Zealand/Australia)

Fearless World War II operative Nancy Wake is best known as one of the most decorated female resistance fighters. Wake was born in New Zealand in 1912 and raised in Australia. She moved to Europe in the 1930s and was living in the region when Nazi Germany began to take control. When the war started, she helped smuggle Allied soldiers and Jews out of France to safety. She was pursued by German forces, who put a price on her head. They called her “The White Mouse” for her ability to evade capture despite a determined, exhaustive manhunt.

Wake was recruited by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) to lead missions inside occupied France. Wake was trained in parachuting, weapons, and guerrilla tactics and then parachuted back into France in 1944. She coordinated the sabotage of German supply routes and troop transports. She led attacks on Nazi outposts and organized the French resistance. She is said to have killed a German soldier with her bare hands because he was moving too slowly to be a threat, but would have raised the alarm if given the opportunity.

Wake survived the war and went on to fight for freedom. Following the liberation of France, Wake continued working with British intelligence. Wake returned to Australia following the war and received multiple honors for her service. Wake received the George Medal from the British, the Médaille de la Résistance from the French, and the Medal of Freedom from the United States. She was one of the most highly decorated women of World War II.

Wake lived a long life following her wartime service. She eventually moved to London and wrote her autobiography, The White Mouse, a first-person account of her experiences as a female resistance fighter. Wake died in 2011 at the age of 98.

Violette Szabo (United Kingdom)

Violette Szabo was a heroic British secret agent who helped fight against Nazi Germany. She was born in France in 1921 but grew up in Britain. When her husband, a French Foreign Legion officer named Étienne Szabo, was killed in action, she wanted to do something to fight back. She joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a group that trained people to be secret agents. She learned to be a spy, to sabotage enemy targets, and to use weapons. In June 1944, she was sent on a mission to France to help the French Resistance.

Szabo was an SOE agent who parachuted into France to do secret missions. Her job was to carry messages, gather information, and help the French Resistance fight the Germans. She was fluent in French and could pass as a local, which made her very useful. In June 1944, on her second mission in France, she was ordered to help sabotage the Germans who were fleeing from the D-Day invasion.

She worked with local resistance fighters, trained recruits, and helped plan ambushes and destroy roads, rail lines, and supply dumps. She had a small red flag in her radio transmitter so her team could find her at night. She was captured in June 1944 while on a mission to sabotage a rail line near Limoges. German soldiers ambushed her group, but she held them off with a submachine gun long enough for the others to escape. She was captured after running out of ammunition.

The Gestapo brutally interrogated Szabo but gave no information. She was sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp, where many female resistance fighters and SOE agents were sent to be tortured and executed. According to a survivor, Szabo was defiant and used to boost the morale of the other prisoners. The Nazis killed her in early 1945, along with two other SOE agents, Denise Bloch and Lilian Rolfe. Szabo was only 23 years old when she died.

After the war, Violette Szabo was awarded the George Cross, Britain’s highest civilian award for bravery, for her sacrifice. She was the subject of books and films, such as Carve Her Name with Pride, and remains one of the most daring and fearless resistance fighters of World War II.

Andrée de Jongh (Belgium)

Belgian resistance fighter Andrée de Jongh was no stranger to danger. During World War II, de Jongh repeatedly risked her life smuggling downed Allied pilots out of Nazi-occupied France and into neutral Spain. Born in 1916, her father was a World War I veteran who inspired her commitment to fighting for justice and against oppression. The Nazi occupation of Belgium gave de Jongh her opportunity to make a difference. She organized a network of trusted contacts called the Comet Line that helped Allied soldiers and airmen escape Nazi-occupied Europe through France and into Spain.

Under constant threat of arrest and imprisonment, she recruited others to form safe houses along the route, produce forged documents, and provide pilots with disguises and other resources to help them pass as civilians. De Jongh herself personally shepherded 118 Allied airmen to freedom, through the Pyrenees Mountains and along a route that was heavily guarded and often patrolled by German soldiers who were also searching for resistance members and escapees.

For successfully leading Allied pilots to safety over and over again, de Jongh became famous on both sides of the English Channel. Her network, the Comet Line, was one of the most successful escape routes of the war and was instrumental in the British intelligence services’ overall efforts.

In 1943, German police captured de Jongh in France. Tortured by the Gestapo, she was eventually sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp for women. A harsh camp for female political prisoners, many resistance fighters died there. De Jongh was one of the survivors.

Released from the camp after the war, de Jongh received numerous awards, including Britain’s George Medal and the U.S. Medal of Freedom. She later worked as a nurse in leprosy clinics in Africa.

Sophie Scholl (germany)

Sophie Scholl was a young German student who stood against the Nazi government despite the danger to her own life. She was born in 1921 into a family of independent thinkers. Like most German children, she initially joined the Nazi youth organizations, but soon became alienated from the regime. In 1942, she co-founded, with her brother Hans and other students, the non-violent White Rose resistance movement. This movement called for an end to Hitler’s dictatorship through the pamphlets they distributed around Munich University. Their goal was to spread the message of justice, freedom, and humanity in a society based on terror and control.

As a member of the White Rose, Sophie Scholl distributed leaflets that openly criticized the Nazi government and called for an end to Hitler’s dictatorship. The leaflets spoke out against the mass murders on the Eastern Front, calling them crimes against humanity. In one leaflet, they wrote, “We will not be silent. We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace!” The group distributed their leaflets in an attempt to spread awareness of Hitler’s crimes and to inspire others to resist. Scholl and her fellow White Rose members knew that if they were caught, they would be killed.

In February 1943, Sophie and Hans were distributing leaflets in Munich University when they were caught by a janitor who reported them to the Gestapo. They were arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo. Scholl refused to implicate her fellow members, even under the threat of death. She took full responsibility for her actions to protect the others. After a short trial, Sophie was sentenced to death. On February 22, 1943, at the age of 21, she was executed by guillotine along with her brother and fellow activist Christoph Probst.

In her final moments, Sophie Scholl was defiant and unrepentant. Witnesses report that she said, “What does my death matter, if through us thousands of people are awakened and stirred to action?” Her courage and sacrifice made her a symbol of resistance against totalitarianism. Today, she is remembered as one of Germany’s most beloved heroes, inspiring future generations to stand up against oppression and fight for justice at all costs.

Noor Inayat Khan (United Kingdom/India)

Born to an Indian father, a Sufi mystic and musician, and an American mother, Noor Inayat Khan grew up in a family steeped in the belief of peace and nonviolence. And yet she fought back, placing herself in extreme peril as a secret radio operator working for the British Special Operations Executive in Nazi-occupied Paris during World War II. Sent into France under the code name “Madeleine,” she transmitted coded intelligence to Allied forces, supporting saboteurs and resistance workers by delivering equipment and information.

Able to hold down a covert position only weeks before the Gestapo typically captured and executed radio operators, Khan became the last working radio link between the Resistance in Paris and London after the arrest of other SOE agents. Ordered to flee to the Spanish border, she refused to leave her post and continued to provide critical information.

On the run and dodging capture for many months, she evaded the enemy by living covertly and traveling constantly. The Gestapo tracked and arrested her in October 1943, after a French informant informed on her. Khan was imprisoned and tortured, but continued to resist and never gave up any information.

Noor Inayat Khan was held and interrogated by the Gestapo, who repeatedly tortured her and beat her with rubber truncheons. As a result of her many beatings, her feet were permanently injured, and she was unable to stand for long periods of time, even while she was still in captivity.

She never gave any information to the Gestapo, and after two escape attempts, she was classified by them as highly dangerous. Khan was kept in solitary confinement for 10 months in the Pforzheim women’s prison, during which time she was kept in chains and was only allowed one hour of exercise a day. On 13 September 1944, she was taken to the Dachau concentration camp and executed. Her last word was reportedly “Liberté.”

Following the end of the war, she was awarded, posthumously, the George Cross, the highest civilian decoration for bravery in Britain, as well as the French Croix de Guerre. After many years of being underappreciated, she is now remembered and honored as a hero of the British SOE and as a symbol of resistance.

Virginia Hall (United States)

Virginia Hall was one of the most successful and notable spies during World War II. She worked for both the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Hall was born in the United States in 1906 and aspired to be a diplomat. She applied to the US Foreign Service but was denied due to a hunting accident that left her with a wooden leg. Hall volunteered for the SOE and was sent to Nazi-occupied France. She became one of the most effective agents in the fight against Nazi Germany.

Hall earned the nickname “The Limping Lady” from her wooden leg, which she named “Cuthbert.” She built and coordinated resistance networks, trained partisans, and organized sabotage missions. Hall attacked German supply lines, set up safehouses, and forged documents. The Gestapo became aware of her and labeled her as one of the most dangerous Allied spies in France. A Nazi manhunt forced her to escape on foot across the Pyrenees mountains to Spain, a nearly impossible journey, especially with a prosthetic leg.

Hall defied this and returned to France in 1944, this time with the OSS. Working under the cover of an old peasant woman, she continued her sabotage operations against Nazi forces. Hall aided in coordinating resistance attacks before D-Day and provided intelligence on German troop movements and sabotage sites. She arranged for weapons drops to resistance fighters and directed them to carry out guerrilla warfare, resulting in the deaths of German soldiers.

Hall’s determination and resourcefulness helped the Allies outsmart the Nazis in occupied France. Her intelligence work was critical in allowing Allied forces to gain the upper hand against the Germans. After the war, she became one of the first female officers for the CIA. Hall was decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross, the only civilian woman in WWII to receive the honor. Virginia Hall’s bravery, tenacity, and ability to accomplish missions against all odds made her one of the most legendary female fighters of the resistance.

Lucie Aubrac (France)

Lucie Aubrac was one of the most daring leaders of the French Resistance. Born in 1912, she was a history teacher who became involved in the fight against the Nazis. As a leader of the resistance movement Libération-Sud, she helped organize sabotage efforts, smuggle weapons, and provide safe houses for fugitives. Aubrac was also an intelligence agent, using her knowledge and skills to great effect. She was one of the most successful female resistance fighters in the underground movement to free France from German occupation.

Aubrac is perhaps best known for her role in the rescue of her husband and several other resistance fighters from Gestapo captivity in 1943. After her husband, Raymond Aubrac, was arrested in Lyon by Klaus Barbie (later known as the “Butcher of Lyon”), Lucie devised a plan to free him.

Posing as a pregnant wife, she gained the trust of the Gestapo and was allowed to visit Raymond in prison. During the visit, she gathered information about his location and the conditions of his confinement. She then led a successful attack on the German convoy that was transporting him to a new prison. Aubrac was able to free her husband and several other prisoners, and the daring rescue became one of the most celebrated acts of the French Resistance.

Throughout the war, Aubrac continued to work with the resistance, fighting until France was liberated. She helped to organize underground operations and to spread the word about the resistance. Aubrac’s story became a symbol of the French Resistance and the role of women in it. It showed that women could be just as effective in the fight against Nazi oppression as men. After the war, Aubrac worked to ensure that the sacrifices of the resistance fighters were not forgotten.

Mila Racine (France)

Mila Racine was a brave member of the French Resistance who selflessly fought to rescue Jewish children. She began helping with an organization during the final years of World War II that was sending hundreds of Jewish children to Switzerland. At a time when the Nazis were intensifying their deportations, Mila worked with an organization called Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE), which was working to rescue Jewish children and youth. She and her co-workers risked their lives to help smuggle the children out of occupied France and lead them through dangerous terrain to safety in Switzerland. She is credited with rescuing numerous young lives and giving families hope when all they faced was deportation to Auschwitz.

Mila worked tirelessly for the cause in secret. She and her underground network of allies and sympathizers opened safe houses, falsified documents, and created escape routes to get the children out of France. Mila led children through the forested, German-guarded border to Switzerland in the dead of night. Her heroism was cemented when she was arrested by the Nazis and imprisoned. She was acting with an aid organization in 1943 when they were discovered, and the Gestapo arrested her. In secret, she was interrogated and then sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp.

She remained stalwart in the face of her situation, and many women who survived the camps cite her as a significant source of fortitude during their time in the camps. She was strong in the face of the brutal labor she was forced into, but in the end, she died in Ravensbrück.

Mila Racine is best known as the selfless member of the French Resistance who saved hundreds of Jewish children. The people that she risked everything to save still remember her to this day as their guardian angel and their hero. Her story remains one of the most essential recollections of courage and strength during the Holocaust.

Yvonne Rudellat (United Kingdom/France)

Yvonne Rudellat was among the first women to be recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to be parachuted into Nazi-occupied France to work with the Resistance. Yvonne Rudellat, born in France in 1897 and a resident of Britain, was fluent in French and, though in her mid-40s, had the spunk and grit for the work.

Recruited by the SOE, she was sent to Britain for training in sabotage, weapons, and communication skills. Rudellat was sent into France in 1942 to work for the SOE’s Prosper network, operating under the codename “Jacqueline.” She parachuted in and set to work collecting intelligence and organizing sabotage. She also played a role in the resistance, including derailing Nazi supply trains, sabotaging communication lines, and helping resupply local underground cells.

Rudellat was hunted by the Gestapo, as was every other SOE agent working behind enemy lines. She worked in constant fear of arrest and betrayal, and often under direct surveillance, but showed no fear and did her work. Her efforts and assistance to the Resistance were invaluable.

In June 1943, a betrayal from within the SOE compromised the Prosper network, leading to a round-up and arrests. The Gestapo apprehended Rudellat along with several of her fellow agents. She was interrogated and again asked to divulge any information. Rudellat would not betray her fellow agents and was deported and moved through several prisons. She was transferred to the concentration camp at Belsen in the spring of 1944.

Conditions at Belsen were barbaric, and she was already ill and malnourished from abuse in prison. She never reached liberation in 1945. Rudellat’s story and work for the SOE were as remarkable as those of the better-known women agents, but she has not received as much attention.

Fernande Keufgens (Belgium)

Fernande Keufgens was just a teenager when she decided to fight against the Nazi occupation of Belgium. In 1925, the Nazis had occupied her home country when she was just 17 years old. Like most young women and men her age in Belgium, she had been required to sign up for labor in Germany in 1942. Fernande decided to escape and hide rather than go. She found work with the Belgian Resistance and quickly became a vital asset and important part of the fight against the Nazis.

Keufgens helped carry out acts of sabotage against German supply trains and equipment. She cut Nazi phone and power lines. She also assisted with gathering intelligence and with providing a haven for downed Allied airmen and escapees. The Nazi regime was merciless to the resistors who were caught or betrayed. There were no chances of being treated humanely by the Gestapo. Torture and execution were the almost certain result. Keufgens knew this when she decided to help, and she didn’t waver or give up. She understood the price that had to be paid for freedom and was willing to do her part.

The young Fernande Keufgens was a part of the Belgian Resistance during the war. The Gestapo was everywhere, looking for members of the Resistance, so they had to be smart, stay off the streets, and live with constant fear for their lives. They had to stay one step ahead of the Nazi forces. Keufgens was involved in the underground Resistance and was on the front lines during the war.

She was able to give insight into what it was like on both sides of the conflict. Fernande was one of the lucky ones as she survived the war. It was not the case for most of her fellow fighters in the Belgian Resistance, and most would die at the hands of the Gestapo. She had a unique perspective, having been so young and involved in the underground. Fernande Keufgens had a remarkable story: from an average teenager to a woman working for the resistance, and then to a heroine.

In the years following the war, Fernande made it her mission to spread the word and ensure that her story was told and shared with future generations. She made public appearances and spoke about her experience.

Hannie Schaft (Netherlands)

Hannie Schaft was one of the bravest of the Dutch resistance fighters of World War II. Schaft was born in 1920 and was a university student in Amsterdam when the Nazis invaded the Netherlands. In protest over the Nazis’ harsh and brutal treatment of Dutch citizens, Schaft dropped out of school and became a resistance fighter. She was a redhead and had to perform some of the war’s most daring missions without being recognized. She soon dyed her hair black, but was still known as “the girl with the red hair” which became a sign of rebellion for those who opposed Nazi rule.

Schaft was involved in sabotage and espionage, as well as assassinating Nazi officers and collaborators with Dutch citizens. A member of the Communist resistance organization Raad van Verzet, Schaft collected intelligence, delivered weapons to other operatives, and joined others in dangerous missions to assassinate key Nazis. Schaft and two female friends and fellow resistance fighters, Truus and Freddie Oversteegen, lured Nazi informants and sympathizers to their deaths or simply shot them on sight. Her two most famous assassinations were of German and Dutch informants. Both killings were acts of retribution and stopped key Nazi operations.

A careful resistance operative, Schaft was arrested by the Gestapo in early 1945 at a checkpoint while driving her car. Her arrest came because she was caught with underground newspapers and a pistol in her purse. She was beaten and tortured during interrogations, but did not divulge the names of her fellow resistance fighters. However, Schaft’s black hair had been growing out, and when it was cut during questioning, her red hair was visible at the roots.

On April 17, 1945, only weeks before the Netherlands would be liberated, Schaft was taken to the dunes of Bloemendaal and shot. Witnesses state that when Schaft fell to the ground after the initial shots, which only wounded her, she said, “I shoot better.” Schaft was shot again and killed.

Hannie Schaft is remembered to this day as one of the greatest of Dutch resistance fighters. She has been officially recognized as a national hero, and each year in the Netherlands, the Dutch people honor her memory and sacrifice. The “girl with the red hair” may have lost her life, but she is still remembered as a woman who defied Nazi oppression and fought for what was right.

Maria Gulovich (Slovakia)

Born in 1921, Maria Gulovich was a 23-year-old Slovakian schoolteacher when she was forced to take part in the Nazi invasion of her country. Hiding Jewish people in her house and helping them escape German-occupied Slovakia, Gulovich later became one of the most important spies and freedom fighters for the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in World War II, which later became the CIA. Trained by the US government, she helped soldiers escape enemy lines, served as a messenger, and spied on Germans and their allies for years, becoming an intelligence leader in the Eastern Front.

Helping freedom fighters escape through enemy lines in Yugoslavia, Maria Gulovich first distinguished herself by gathering and sending encrypted notes, transporting weapons, and supplying food and other vital resources to the guerrilla forces fighting the Nazis. In 1944, she joined a top-secret OSS team deep in the mountains of Slovakia, where she spent months hiding from the Nazis in frigid conditions, surviving near-starvation, and working to lead a six-man team of intelligence agents. Aided by her superior instincts, Maria Gulovich became an essential leader of the American resistance in Slovakia.

German forces were gradually defeated after months of constant attacks on Nazi sympathizers, resistance forces, and foreign military teams operating deep in occupied territory. With Gulovich’s support and intelligence-gathering, the region was essentially liberated, due in large part to local partisan groups and to foreign teams on the ground like Gulovich’s. By war’s end, Maria Gulovich had become one of the most decorated agents of the OSS, offered a path to immigrate to the United States by the American military. She would go on to live out the rest of her life in the United States, becoming a mother and grandmother.

Maria Gulovich, who was awarded the Bronze Star for her service in World War II, rarely spoke about her experiences in the war until well into her later life. Her story is one of the best-known examples of women’s service in resistance efforts and a reminder of just how much difference a single person with little formal training or experience can make on the world’s most important stages.

Josette Durrieu (France)

Josette Durrieu was a member of the French Resistance during World War II. She risked her life to fight against the Nazi occupation of France. Durrieu was a young woman living in occupied France who joined the underground resistance movement. She worked with resistance networks to sabotage German operations and gather intelligence. Durrieu helped plan and execute attacks on Nazi infrastructure and was involved in gathering information and coordinating resistance missions. She was motivated by a strong sense of justice and a desire to see her country free from Nazi tyranny.

One of Durrieu’s most significant contributions to the resistance was her work in sabotaging Nazi railway lines. Resistance fighters targeted these railways to disrupt German supply lines and troop movements. Durrieu and others in the resistance would gather information about the location of these lines and then use explosives to damage the tracks and bridges, making it more difficult for the Nazis to transport goods and reinforcements. Her efforts in this area were part of a broader resistance campaign that helped weaken German control over occupied France in the final years of the war.

Durrieu continued to work with the resistance until the liberation of France. After the war, she did not shy away from public service and became a prominent political and governmental figure in post-war France. Her work after the war continued her efforts during the resistance, as she remained committed to rebuilding and strengthening her country. Durrieu’s story is an example of how resistance fighters not only played a role in winning the war but also helped to shape the future of their countries in the post-war period.

Lise Børsum (Norway)

Lise Børsum was a member of the Norwegian Resistance during World War II who worked to save others’ lives. When the Nazis occupied Norway, Børsum joined an underground group working to help people, particularly Jews, escape the country. She assisted in a network that helped Jews and other people the Nazis targeted to leave Norway for neutral Sweden safely. For a time, she and her fellow resistance members were successful in this, but it was hazardous work as the Gestapo was always looking for people to arrest and escape routes to shut down.

In 1943, someone reported her, and she was arrested and taken to Grini prison before being deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany. There she was, one of the many female prisoners of war and resistance members who were imprisoned and treated with great cruelty by the Nazi regime. The conditions at Ravensbrück were inhumane at best, and Børsum had to rely on his inner resources to keep going. She survived, but many of her cellmates did not, and she always described the place in powerful terms in her writing and testimony. After the war, she would use her experiences there to warn about the dangers of political control and totalitarianism.

Børsum was also a human rights advocate and continued to work to make sure people knew about the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps. She published several books and essays that describe her experiences during the war and at Ravensbrück. Her writing has been influential and is still taught as a piece of Norway’s history. In addition to her work as a writer, she was involved in efforts to promote human rights and to draw attention to the ongoing threat of political repression.

Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya (Soviet Union)

Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya was one of the most renowned Soviet partisans who fought against the Nazi occupation. She was born in 1923 in a patriotic family that deeply loved their country. In 1941, when Germany attacked the Soviet Union, Kosmodemyanskaya joined a partisan unit, a secret sabotage group of the Red Army, and started working in the occupied areas. Her task was to destroy the German supply depots, cut off their communication lines, and attack their positions. For an 18-year-old girl, she was fearless and resolute, and never gave up no matter how dangerous her situation was.

In November 1941, Kosmodemyanskaya was on a mission near the village of Petrishchevo when she was spotted and captured by the Nazis after setting fire to their headquarters. She was tortured and interrogated by the Germans, but she never revealed any information about her group or gave any of her comrades away. She even allegedly taunted the Germans and screamed, “We are Soviet partisans and we are fighting you to the last drop of blood.” Kosmodemyanskaya’s bravery and defiance made her an ideal propaganda tool for the Nazis.

On November 29, 1941, the Nazis shot and killed Zoya in front of the villagers as a “terrible example.” Before she was killed, Kosmodemyanskaya reportedly shouted, “You can’t hang all 170 million of us.” After the war, Kosmodemyanskaya became one of the Soviet Union’s most decorated heroes. The image of the young, smiling, and fearless partisan was widely disseminated, and her sacrifice became a national myth. She was posthumously awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union, the country’s highest honor.

Kosmodemyanskaya’s name has become a symbol of Soviet patriotism, and she is still a role model for many young people in Russia today. Many schools, streets, and monuments have been named after her, and her legacy has been kept alive in literature, films, and songs. She is now remembered as a fearless partisan who gave her life for her country.

Zivia Lubetkin (Poland)

Zivia Lubetkin is one of the few women who led the Jewish resistance during World War II. She was born in Poland in 1914 and, before the war, was an active member of the Zionist youth movements. When the Nazis occupied Poland and forced the Jews into ghettos, she took an important role in organizing armed resistance to the Germans. Lubetkin was one of the founding members of the Jewish Fighting Organization (ŻOB) and had a leading role in organizing the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, one of the most famous acts of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust.

Lubetkin fought in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in April of 1943. She fought in the underground bunkers of the ghetto with her fellow fighters, with homemade bombs and a few smuggled weapons, against the heavily armed and much larger German forces. She saw the ghetto destroyed and many of her fellow fighters killed, but she would not be taken alive. Lubetkin and a few other resistance fighters escaped the ghetto through the sewers and made it to the Aryan side of Warsaw. From there, she continued to fight as part of the Polish resistance in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Her survival through the uprising is a miracle.

In an interview about the uprising, Lubetkin stated, “We saw the ghetto burning, we saw our people being slaughtered, and we understood that history had placed us in a unique moment—we had to fight.” These words truly express the despair and resolve of the Jewish people who were forced into the Warsaw Ghetto.

After the war, Lubetkin helped many Jewish survivors to recover and start their lives over again. She immigrated to Israel, where she helped to found the Kibbutz Lohamei HaGeta’ot to remember the Holocaust and the resistance movement. She also testified in the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Her story is one of bravery, heroism, and strength in the face of overwhelming opposition.

Odette Sansom (France/United Kingdom)

Odette Sansom was a heroic World War II spy, a British agent of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) who was a leader in the French Resistance. Born in France and living in Britain at the time, Odette was recruited by the SOE in 1942 and parachuted back into Nazi-occupied France. Posing as a clerk for a French shipping company, she helped the French Resistance with sabotage operations, transmitting intelligence reports to London, and setting up safe houses for Allied agents. The Gestapo hunted her and many other SOE agents.

In 1943, Odette was betrayed by a double agent and was captured by the Gestapo, who arrested her along with SOE agent Peter Churchill. She was imprisoned in the infamous Fresnes Prison, where she was interrogated and tortured. In an effort to gain information about the French Resistance, Odette was burned, beaten, and starved, but refused to give up information. She even told the Gestapo that Churchill was her husband and that he was an important figure, so the Gestapo would not torture him. Her courage and endurance under such horrific conditions were legendary.

After months of torture, Odette was transported to Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she was placed in solitary confinement, suffered extreme malnutrition, and witnessed the Nazi’s atrocities. She never gave up her will to live. As the end of the war approached, Odette was moved to another camp, where a German officer who had sympathized with her plight was afraid of the Allied reaction to the concentration camps and surrendered her to American forces in April 1945. She was a miracle of survival.

After the war, Odette became the first woman to be awarded the George Cross, Britain’s highest civilian honor for bravery. She testified at war crimes trials against her captors, and later her story was made into the 1950 film Odette. A legend of resistance during World War II, Odette Sansom was an example of the human spirit overcoming the most horrific conditions.

Cécile Rol-Tanguy (France)

Cécile Rol-Tanguy was an intrepid leader and a staunch figure in the French Resistance, organizing and fighting in the Paris Uprising of 1944. She was born in 1919 in a politically charged family of fascist fighters and moved to Paris to study to become a medical doctor. It was during this time, when Germany had successfully overtaken France, that she grew determined to join in on the country’s fight against the Nazi occupation and joined the communist resistance movement, working alongside her husband Henri Rol-Tanguy. Rol-Tanguy served as an underground messenger, gathering and relaying information to allied resistance cells in the city and coordinating the delivery of weapons and sabotage messages.

The most important of her actions was the liberation of Paris, during which she worked with other members of the French Forces of the Interior to organize the August 1944 Paris Uprising. Working in secret hideouts, she was in charge of passing down key information on German positions to Paris resistance fighters so they could organize and launch attacks from multiple points around the city. She helped spread the call to arms from the underground resistance, so Parisian civilians could join the battle and rush to barricades and points of interest in support of the resistance.

Her actions during the Battle of Paris turned the tide of the war as they were one of the final massive operations against the Nazi forces that left a majority of Europe free from their occupation.

In addition to her role as a resistance message bearer, Rol-Tanguy also worked in sabotage operations to break German communication networks. She also provided resistance members in danger of capture with safe houses, false documents, and IDs. Her role as a resistance spy and operative put her in direct danger as the Gestapo and Nazi German secret police were on a constant hunt for resistance fighters. Her ability to evade capture while successfully handling resistance operations was an essential factor in the resistance’s success, and her continued role in their operations during the war was critical in setting up subsequent victories.

Post-war, Rol-Tanguy remained an advocate for the underground resistance and for honoring resistance fighters for their role in the conflict. She was among the highest-decorated in France for her service, but as a woman, her efforts were marred by obscurity as the resistance continued to focus on the roles of its men and veterans. She used her remaining time to speak up for women’s role in the resistance and to ensure their efforts were remembered.

Lepa Radić: (Yugoslavia)

Lepa Radić was a young Yugoslav Partisan who fought against Nazi Germany during World War II. She was born in Bosnia in 1925 and was just 14 years old when she joined the resistance movement against the Axis powers. Radić was a member of the Communist Youth League, and she later joined the Partisans in their fight against the Nazis and their puppet regimes.

Radić was known for her bravery and determination as a fighter. She helped distribute propaganda, assisted in sabotage operations, and even delivered weapons to resistance fighters. In the early months of 1943, during the Battle of Neretva, Radić was captured by German forces. They were occupying a village that the Nazis were attacking, and Radić was helping to defend the civilians who were trying to escape. The Nazis interrogated Radić and tried to force her to reveal the names of her fellow resistance fighters. Radić bravely refused to betray her comrades, even when the Nazis threatened to torture and execute her.

The Germans eventually hung Radić, but not before she made a final stand of defiance. As she was being led to the gallows, the German officers told her that if she gave up the names of the resistance leaders, they would spare her life. Radić is said to have replied, “I am not a traitor to my people. My comrades will avenge me.” Moments later, she was executed at the age of 17.

Radić’s story quickly spread and became a symbol of Yugoslav resistance to Nazi occupation. Her image, standing on the gallows and refusing to give in to her captors, became a rallying cry for the Partisans and a symbol of hope for the people of Yugoslavia. Radić was posthumously awarded the Order of the People’s Hero, one of Yugoslavia’s highest honors, and her story was immortalized in songs, poems, and films.

Radić’s legacy as a symbol of resistance and patriotism continues to this day. Streets, schools, and monuments have been named after her, and her story has been passed down through generations of Yugoslavs. She remains a powerful example of the impact that even the smallest actions can have in the fight against tyranny.

Hélène Viannay (France)

Hélène Viannay worked against the Nazi oppressors with words and deeds. She is a member of the Resistance movement and a leader. With her husband, Philippe Viannay, Hélène co-founded Défense de la France, the most successful and influential underground newspaper. In 1944, the newspaper had a circulation of almost half a million copies. These papers were brimming with anti-Nazi propaganda and graphic descriptions of German war crimes, and were full of encouragement to resist the occupation. She ran the paper with a certain boldness that made her an easy target for the Gestapo. However, she took the risk in the name of truth.

Viannay not only published newspapers and wrote articles for them; she also did her best to help those persecuted by the Nazis. She organized safe passage for Jewish families, forged papers, and found hiding places to ensure that people would not be sent to the camps. Countless numbers of Jews were saved from the Gestapo by her.

In addition to Jews, Viannay hid escaped Allied pilots and members of the resistance who were looking to escape the enemy’s clutches. She was always willing to lend a hand, and her life is an example to all of us. Even after her underground network was infiltrated and destroyed by the Gestapo, she still published the Défense de la France newspaper with the help of her network, surviving until liberation.

Hélène Viannay was the unsung heroine of the French Resistance. She knew that the war against the German oppressors was being fought as much with words and truth as it was with weapons. Viannay not only fought against the Germans; after the liberation of France, she established organizations that supported resistance fighters and carried out social programs for displaced persons.

Wanda Gertz (Poland)

Wanda Gertz was a Polish resistance leader who did not back down to the Nazis or anyone else’s expectations. During World War II, Gertz defied the Nazi occupation and social norms by becoming an underground resistance leader. She was born in 1896 and was already a decorated World War I war hero when she disguised herself as a man to fight. When Germany invaded and occupied Poland at the start of World War II, she joined the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), a Polish resistance organization. Using her previous military experience, she led sabotage missions and trained women in the use of weapons to fight the Nazis.

Gertz was in charge of planning and coordinating the underground resistance activities against the Germans. This included intelligence-gathering operations as well as sabotage operations designed to disrupt Nazi supply lines and other military targets. As the war against the Germans continued, she focused on building up the network of resistance fighters, including recruiting and training women to support the fight against the Nazis. Gertz also took a prominent role in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, leading an all-female sabotage unit during the fighting and proving that women could fight and be just as competent as men in war.

In late 1944, however, Gertz was captured by the Gestapo and sent to a concentration camp, where she was held and interrogated in deplorable conditions. She was eventually deported to Ravensbrück, a concentration camp for women that was filled with women resistance fighters like Gertz. In the camp, she refused to give in and instead just bided her time, holding out until the end of the war in the hopes that she would be able to survive and see Poland liberated from the Nazis.

After months of torture and abuse, the war ended, and Gertz was finally liberated from the camp, but the physical and mental toll of her time there left her with injuries that she would have to live with for the rest of her life.

In the years following the war, Gertz remained active in service to her country but was largely ignored by the communist government that took power in Poland, which had little use for former resistance members. Gertz lived a quiet life but is remembered as a Polish war hero and a testament to the power of women in the Polish resistance.

Krystyna Skarbek (Poland)

Krystyna Skarbek was one of the most intrepid female spies of World War II, working for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). She was born in Poland in 1908 and had a strong sense of patriotism. She volunteered for British intelligence after the German invasion of Poland in 1939. Skarbek was one of the first women recruited by the SOE. She was trained to spy on the enemy, help resistance fighters, and sabotage Nazi operations in occupied Europe.

Skarbek was skilled at evading capture and using her wits to outsmart the enemy. She operated in Poland, Hungary, and France. Skarbek used her cunning and charm to travel with fake identities and infiltrate Nazi-occupied territories. One of her most well-known escapades was when she bluffed the Germans into releasing fellow SOE agents from the Gestapo by convincing them that if they killed the agents, the Allies would retaliate against them immediately.

Her quick thinking and fearlessness earned her the respect of the Allied forces and saved the lives of many. She was eventually captured by the Gestapo but managed to escape using her knowledge of German and her charm. Skarbek’s resourcefulness and ability to manipulate situations earned her the respect of other resistance fighters and intelligence officers.

She was awarded the George Medal and the Croix de Guerre for her exceptional service. Despite her wartime contributions, Skarbek was neither granted British citizenship nor recognized by the government. In 1952, she was murdered in London by a former colleague. Krystyna Skarbek’s legacy as one of the most courageous and resourceful female resistance fighters of World War II lives on.

Female Resistance Fighters & Unsung Heroes of the Resistance

These 20 women are only a handful of the thousands of women who risked their lives in the underground. These women all had different stories. They came from different backgrounds and areas of Europe. Some lived their lives in secrecy; their names will never be known. But even though we know these women and their stories, that doesn’t mean they were more important than those we don’t. These women did what they did because they wanted to resist the Nazi invasion, occupation, and oppression. They passed notes, destroyed supplies, and fought with weapons in their hands. Each one of them, in some small way, weakened the Nazi war effort and contributed to the Allied victory in WWII.