20 Greatest Nomadic Horse Cultures in World History

Nomadic horse cultures have been a significant force in world history. Their unparalleled mobility, skill in mounted warfare, and profound connection to the land have allowed them to influence and conquer regions far beyond their steppes. From the Eurasian heartlands to the American plains, these societies have been characterized by their reliance on the horse. The nomadic lifestyle centered around horseback riding, herding, and a deep understanding of the terrain. This gave their warriors the speed and agility to conduct lightning raids, create sprawling empires, and frequently outpace and outflank the mightier armies of sedentary civilizations.

This article presents twenty of the most powerful and influential nomadic horse cultures from world history; civilizations that built not cities, but saddles.

Scythians: Nomads of the Golden Steppes

Era: c. 900 BCE – 200 BCE

Region: Pontic Steppe (modern Ukraine, southern Russia)

Highlights: Among the earliest nomadic horse archers; known for gold-filled burial mounds and exceptional cavalry tactics.

Legacy: Inspired Greek legends like the Amazons; influenced Persian and Greek military thought.

Famous Historical Figures: King Ateas, Queen Tomyris, Anacharsis

Originating in Central Asia and beginning their westward migration around the 9th century BCE, the Scythians were one of the first great nomadic horse cultures to rule the Eurasian steppe. Expanding into the Pontic Steppe, the Scythians established an empire that spanned from the Black Sea to the borders of Persia. Characterized by mobility and mastery of mounted archery, the Scythians were heavily dependent on the horse for war, herding, and identity. Herodotus claims, “None who attacks them can escape, and none can catch them if they desire not to be found,” referencing their elusive guerrilla warfare.

The Scythians had a lasting impact on military strategy and the regional balance of power during their time. In the 6th century BCE, a massive Persian army led by Darius the Great was sent to subdue the Scythians. Rather than engaging the Persians directly, the Scythians employed hit-and-run tactics, feigned retreats, and lured the invaders deeper into the steppe. The Scythians employed these tactics so effectively that the invaders could not find enough food or water, and Darius had to order a withdrawal.

The victory of the Scythians over such a massive army established their fearsome reputation. It further set an example in Eurasian warfare for the strategic use of steppe nomads. The Scythians’ influence also spread to neighboring peoples such as the Greeks, with whom they had both trade and conflict.

The Scythians were eventually displaced by other nomadic groups, such as the Sarmatians, and by the 2nd century BCE, they had largely been assimilated into the populations they once ruled. The legacy of the Scythians, however, would outlive their empire. Their kurgans, or burial mounds, show an opulent culture of gold artisanship and warrior ideology to the world. The impact of the Scythians on nomadic warfare, steppe art, and regional diplomacy would foreshadow the rise of later Eurasian horse cultures such as the Huns and Mongols.

Sarmatians

Era: 5th century BCE – 4th century CE

Region: Eastern Europe and the Caucasus

Highlights: Heavy cavalry with rich warrior traditions; served in Roman legions.

Legacy: Influenced medieval chivalric traditions; ancestral to some modern Eastern Europeans.

Famous Historical Figures: Queen Amage, Zopyrion, Amandus (Sarmatian general under Rome)

The Sarmatians were a confederation of tribes known for their warfare that emerged in the eastern part of the Scythian world in the 5th century BCE. They were Scythian in language and culture, but they rapidly eclipsed them as the premier nomadic force in the Pontic Steppe. They were renowned as an elite heavy cavalry culture, developing scale armor for both horse and rider, a tactic that would re-emerge in medieval Europe through the knights. To Roman writers, such as Tacitus, they were a fearsome and battle-hardened people, accustomed to fighting with long lances and employing shock tactics.

The Sarmatians were closely associated with the Roman Empire, frequently being in conflict and involved in Eastern European wars. During the Marcomannic Wars in the 2nd century CE, Sarmatian cavalry were recorded to have routed Roman legions alongside the Germanic tribes on the Danube. Sarmatian cavalry was so formidable that later on they were recruited as auxiliaries into the Roman army. The Sarmatians, who had units in Britain, contributed to the Arthurian legend through their equipment and tactics.

In the 4th century CE, the Sarmatians began to decline due to the Gothic migrations and the push of the Huns from the east. Many were assimilated into other groups or settled as vassals inside the Roman Empire. Although they did not continue as an identifiable culture, the Sarmatians are recognized as one of the most powerful horse cultures in history, both in reality and through their influence on myth.

Xiongnu: China’s First Nomadic Nemesis

Era: 3rd century BCE – 1st century CE

Region: Mongolia and Northern China

Highlights: Confederation that clashed with the Han Dynasty and inspired Chinese military reforms.

Legacy: Their conflict helped shape the Great Wall; likely precursors to the Huns.

Famous Historical Figures: Modu Chanyu, Laoshang Chanyu, Yizhixie

The Xiongnu were a confederation of nomadic tribes in Central Asia that first appeared in the 3rd century BCE. They are one of the first organized nomadic empires to have interacted and pitted themselves against a sedentary superpower of their time: Han China. A single leader named Modu Chanyu is credited for uniting the Xiongnu and creating a centralized military force that controlled the north. The Xiongnu soon became a constant threat to China, as they raided agricultural communities, forcing the Han to maintain a costly defensive and diplomatic posture. The Xiongnu were portrayed in Chinese historical texts as barbaric horsemen who “live on their horses.”

One of the most significant impacts that the Xiongnu had on early Chinese history is their influence on the Han’s frontier policy. After decades of invasions, Emperor Wu of Han initiated several large-scale military campaigns in the 2nd century BCE to drive the Xiongnu out. These campaigns saw major victories for the Han such as the Battle of Mobei in 119 BCE, where Han General Wei Qing led an invasion deep into Xiongnu territory. However, the wars with the Xiongnu continued for decades after, and the Han responded by building and expanding the Great Wall to keep them at bay.

The Xiongnu confederation began to decline in the 1st century CE as the empire splintered due to internal conflicts and pressure from other steppe tribes. Some of the Xiongnu remnants fled west and may have been the ancestors of future steppe powers, such as the Huns. Although their empire was short-lived, the Xiongnu had a profound influence on the structure of nomadic warfare and a significant impact on early Chinese frontier policy, diplomacy, and infrastructure.

Alans: Cavalry Kings of the Caucasus

Era: 1st – 5th centuries CE

Region: Caucasus and Central Asia → Europe

Highlights: Fierce cavalry who migrated westward, joining the Vandals and sacking Rome.

Legacy: Ancestors of the modern Ossetians; influenced Roman frontier defenses.

Famous Historical Figures: Goar, Respendial, Sangiban

The Alans were a people from the steppes of Central Asia who first emerged in historical records during the 1st century CE. As a branch of the Sarmatian confederacy, the Alans were one of the most powerful groups of nomadic cavalry, specializing in heavy lances and known for the speed and discipline of their horsemen. Ranging across the lands between the Don River and the Caucasus, they were a constant presence for centuries, raiding and bargaining with the Roman and Persian empires, described by Ammianus Marcellinus as “tall, fair-haired, and warlike.”

In the 4th century, the Alans found themselves at the forefront of a massive westward migration of the Huns. Some crossed the frontiers of the Roman Empire, mixing with the Vandals and Suebi during the next several decades of mass migration. A coalition of such peoples, including Alans, crossed the frozen Rhine in 406 and moved through Gaul and into North Africa, ultimately sacking Rome and establishing the Vandal Kingdom of Carthage. Others settled in the Caucasus, from where they later fought a long series of conflicts with invading Arabs. The Eastern Alans in the Caucasus are considered the direct ancestors of the Ossetian people.

The Alan people would make an indelible mark on history before being overwhelmed by the other peoples. Their methods of cavalry warfare would prove influential for the Romans and later medieval European armies. They were also among the first nomadic peoples to be fully absorbed into the power dynamics of Western Europe, both as aggressors and as kings of stable realms in their own right.

Huns: The Storm from the Steppes

Era: 4th – 5th centuries CE

Region: Central Asia → Eastern & Western Europe

Highlights: Terrified Europe with lightning raids; heavily influenced the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Legacy: Changed European geopolitics and inspired centuries of steppe warfare imitation.

Famous Historical Figures: Attila the Hun, Bleda, Uldin

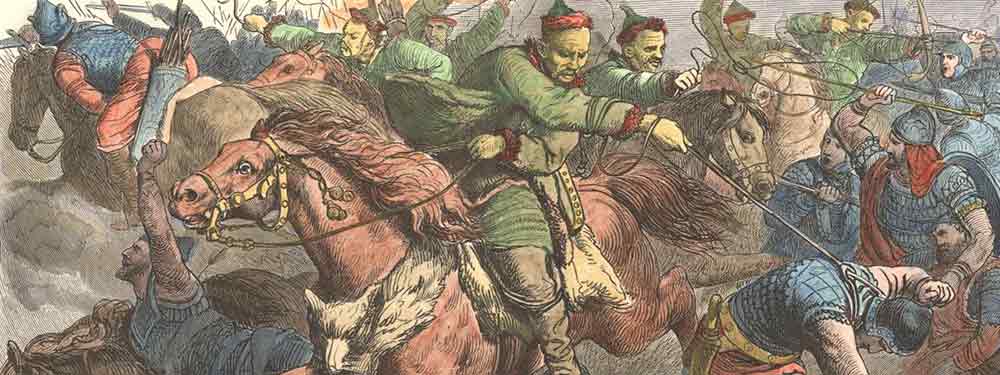

The Huns were a nomadic people who appeared on the steppes of Central Asia before the 4th century CE. Over the next few decades, they would sweep across the Eurasian steppe and into Europe, sowing chaos and destruction in their wake. The exact origins of the Huns are unclear, but they are believed to have been related to the Xiongnu and other steppe peoples. The Huns were expert horsemen and archers, and their ability to move quickly and strike fear into the hearts of their enemies was a new development in warfare.

By the time the Huns crossed the Volga River, their advance had already driven millions of Germanic people west into Roman lands, setting in motion events that would ultimately lead to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The Huns reached the peak of their power in the mid-5th century under the leadership of Attila.

As the Roman writer Jordanes said of him, “Attila was a man born into the world to shake the nations, the scourge of all lands.” Attila led his armies across the Balkans and into Gaul, and in 451 CE, he was met by a Roman-Visigothic force at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains. Although the battle was inconclusive, it marked the end of the Hunnic invasion of Western Europe and is considered one of the largest and most significant battles of Late Antiquity.

After Attila’s death in 453 CE, the Hunnic confederation quickly disintegrated, as subject peoples rebelled against their overlords. The Huns disappeared as a major power within a generation, but their influence would continue to be felt for centuries to come. The Huns were one of the most significant factors in the fall of the Western Roman Empire, and their movements reshaped the ethnic makeup of Europe. The Huns were also responsible for the spread of fear and terror throughout Europe, and their reputation would continue to haunt Europe for centuries. The Huns’ composite bows, reliance on fast cavalry raids, and psychological warfare were adopted by later nomadic empires such as the Avars and Mongols.

Hephthalites (White Huns): Conquerors Between Empires

Era: 5th – 7th centuries CE

Region: Central Asia and Northern India

Highlights: Conquered major parts of the Sassanid and Gupta Empires.

Legacy: Blended nomadic and settled cultures; left an architectural and political legacy in Central Asia.

Famous Historical Figures: Toramana, Mihirakula, Khushnavaz

The Hephthalites, sometimes referred to as White Huns, originated in Central Asia around the 5th century CE. Unlike Attila’s Huns, they were a different ethnic group but also had a nomadic background and were renowned for their formidable cavalry. They formed a confederation that controlled parts of modern Afghanistan, Central Asia, and northern India. Byzantine chronicler Procopius called them “Huns in name but not in customs,” highlighting their distinct culture. The Hephthalites capitalized on the power vacuum between the declining Sassanid and Gupta empires.

One of their most significant military achievements was the defeat of the Sassanid Persian king Peroz I in 484 CE, a devastating blow to the Persian Empire. The Hephthalites imposed a substantial tribute on the Sassanids and dominated eastern Iran for several decades. They also conducted campaigns deep into India, contributing to the decline of the Gupta Empire and altering political landscapes across the subcontinent. Their success was attributed to their elite cavalry, strategic use of terrain, and swift movement.

The Hephthalite Empire began to fragment in the late 6th century due to pressure from a new alliance between the Sassanids and the emerging Turkic Khaganate. Internal divisions and external invasions contributed to their eventual disappearance from historical records. However, their legacy persisted. Militarily, they introduced new tactics and weaponry to the regions they conquered. Politically, their incursions contributed to the destabilization of major empires and the emergence of new regional powers. The Hephthalites’ story highlights the transient nature of nomadic empires situated between rival superpowers.

Göktürks: The First Empire of the Turks

Era: 6th – 8th centuries CE

Region: Central Asia

Highlights: United Turkic peoples became a powerful steppe empire with written records from Old Turkic.

Legacy: The first empire was identified as “Turk” and was foundational to future Turkic identities.

Famous Historical Figures: Bumin Qaghan, Istemi Qaghan, Bilge Qaghan

In the mid-6th century CE, the Göktürks first united under a political entity, comprising various Turkic tribes that had previously migrated independently, thereby establishing the first Turkic empire. They initially emerged in the Altai Mountains and, after breaking away from the dominant Rouran Khaganate, soon created a vast nomadic empire that spanned from Manchuria to the Caspian Sea. Claiming a divine right, the Göktürks were also known as “Celestial Turks.” They developed the Old Turkic script, and their most famous inscription, found on the Orkhon steles, states, “The Turkish people, who lost their empire and their lord, gained it again by their own strength.”

At the height of their power, the Göktürks controlled the Silk Road and emerged as a central force in East-West diplomacy and commerce. They often fought against and, at times, allied with Chinese dynasties like the Sui and Tang, and their influence fluctuated with shifting alliances. Leaders like Bumin Qaghan and his son Istemi established strong political-military alliances with states like the Sassanid Persians against their rivals, the Hephthalites. They often led successful campaigns against these and other neighboring nomadic peoples.

The empire had collapsed in the early 8th century into two separate eastern and western khaganates due to power struggles and pressure from the Tang and Umayyad Caliphate. The Tang dynasty quickly took advantage of this internal division and, by 630 CE, had defeated the Eastern Göktürks. Although the Göktürks eventually fell, their legacy was lasting, having laid a strong foundation for subsequent Turkic empires to rise and significantly contributed to the cultural and political identity of Central Asia through their language, script, and nomadic empire-building model.

Avars: Steppe Warriors of the Balkans

Era: 6th – 9th centuries CE

Region: Central Asia → Pannonian Basin

Highlights: Fought Byzantines and resisted Charlemagne’s expansion; ruled a significant khaganate in Europe.

Legacy: Introduced Central Asian steppe warfare to the Balkans.

Famous Historical Figures: Bayan I, Theodoric of the Avars, Tudun

The Avars entered Eastern Europe in the mid-6th century CE. It is believed that they were descendants of an alliance of Central Asian nomadic tribes driven westward by the expansion of the Göktürks. In the Carpathian Basin, they founded the Avar Khaganate, a nomadic-style state which held sway in the region for two centuries. Like other steppe polities, they were led by a khagan (ruler) and maintained a mounted aristocracy. They were perceived with suspicion by the Byzantines, who depicted them as “fierce and cunning horsemen who obeyed no one”.

The Avars are known for their participation in the 626 CE siege of Constantinople, when they and the Sassanids launched an unsuccessful but impressive effort to capture the Byzantine capital. At its height, their state stretched across much of the Balkans and Central Europe, with their military might subjugating various Slavic and Germanic tribes. Adoption of stirrups, probably from the East, provided them with a major tactical advantage in cavalry warfare.

In the late 8th century, under increasing pressure from the expanding Frankish Empire of Charlemagne, the Avar Khaganate began to disintegrate. After a series of defeats in the early 9th century, its aristocracy had disintegrated. Its former lands were gradually taken over by Slavic and Frankish settlers. The Avars remain important for having introduced steppe-style military innovations to Europe and as a link between East and West.

Bulgars: Nomads Who Forged a Nation

Era: 7th – 9th centuries CE

Region: Central Asia → Balkans

Highlights: Nomadic warriors who founded the First Bulgarian Empire.

Legacy: Merged with Slavs to create modern Bulgaria.

Famous Historical Figures: Khan Asparuh, Khan Krum, Khan Omurtag

The Bulgars were a Turkic nomadic group that emerged in Central Asia. Pushed westward by more dominant steppe tribes, they migrated into Europe by the 5th century CE. In the 7th century, under Khan Asparuh, a group of Bulgars crossed the Danube, defeated the Byzantine army at the Battle of Ongal in 680 CE, and established the First Bulgarian Empire, a state characterized by its nomadic, Slavic, and Byzantine elements. Byzantine sources describe the Bulgars as “ferocious riders,” adept in cavalry warfare and political strategy.

As the Bulgarian state stabilized, the Bulgars increasingly adopted sedentary lifestyles and Christianity, evolving from a nomadic confederation to imperial rulers. Under Khan Krum in the 9th century, the Bulgarians inflicted one of the most significant defeats on the Byzantines at the Battle of Pliska, where Emperor Nikephoros I was killed, and his skull allegedly turned into a drinking cup by Krum. The empire prospered under Krum’s successors, expanding its territory and influence across the Balkans. Over time, the Bulgar ruling elite assimilated into the Slavic population, giving rise to the medieval Bulgarian identity.

While the nomadic origins of the Bulgars became a distant memory, their legacy persisted in the foundation of a European kingdom that would endure, in various forms, for centuries to come. They represent a rare case of a steppe culture that successfully transitioned into a sedentary, enduring state, leaving a lasting impact on the cultural and political development of Southeastern Europe.

Uighurs: Diplomats of the Steppe and Silk Road

Era: 8th century – Present

Region: Mongolia → Xinjiang

Highlights: Played a significant role in Tang-era China; skilled in diplomacy, trade, and culture.

Legacy: Transitioned from nomadic rule to an urban, literary society along the Silk Road.

Famous Historical Figures: Kutlug Bilge Kagan, Bogu Khan, Qutluq

The Uighurs first appeared in historical records during the mid-8th century CE, succeeding the Göktürks and forming the Uighur Khaganate in Mongolia by 744 CE. They established a significant presence in Central Asia, striking a balance between nomadic power and a cultivated diplomatic policy. A pivotal alliance was with the Tang Dynasty during the An Lushan Rebellion in 755; Tang records laud the speed and discipline of the Uighur cavalry in quelling the rebellion, and in return, they were granted political influence and access to Chinese trade and culture.

At their zenith, the Uighurs controlled important segments of the Silk Road and developed a cosmopolitan empire with its center at Ordu-Baliq. They showed evidence of Buddhism and Manichaeism influences and incorporated elements of Chinese bureaucratic organization, demonstrating an unusually high level of synthesis between nomadic and sedentary ways of life. The Uighur Khaganate collapsed due to internal divisions and Kirghiz invasions by 840 CE. Many Uighurs migrated southwest to the area now known as Xinjiang, where they founded several kingdoms and progressively settled into a more trade-oriented and urban existence.

The Uighurs’ influence persisted long after the disintegration of their empire, contributing to the cultural and religious diversity of Central Asia. The Uighur script had a lasting impact on the Mongolic and Manchu languages. Their ability to adapt politically and their diplomatic savvy allowed them to serve as intermediaries between the steppe and the settled world, one of the most urbane and sophisticated nomadic powers in history.

Pechenegs: Raiders of the Western Steppe

Era: 9th – 11th centuries CE

Region: Central Asia → Eastern Europe

Highlights: Frequently raided and fought Byzantium and the Kievan Rus’.

Legacy: Eventually assimilated into Eastern European cultures; feared mercenaries and warriors.

Famous Historical Figures: Kurya, Khan Ildegiz, Tonuzoba

The Pechenegs first appeared in the 9th century CE and were a Turkic nomadic confederation who lived on the steppe lands between the Volga and the Danube. Oghuz and Khazar expansion forced them to move west and they came to dominate the borderlands of the Byzantine Empire and Kievan Rus’. Byzantine chroniclers referred to them as “a restless people, skilled in war and cunning in strategy”. The Pechenegs were expert horse archers who excelled in mobile warfare and made frequent lightning raids into their neighbours’ lands. They became allies and enemies of their powerful neighbours at various points.

In 968 CE, the Pechenegs laid siege to the city of Kiev during the absence of its prince Sviatoslav I, who was on campaign. The siege was ultimately lifted, but it demonstrated that they were capable of menacing large urban centers. The Pechenegs were sometimes hired as mercenaries by the Byzantines and were also a violent enemy of the empire on other occasions. In 1091, the Byzantines, with the assistance of the Cumans, routed the Pecheneg army in the Battle of Levounion and effectively crushed their power, thereby ending their threat as an independent force.

The Pechenegs were largely assimilated by their neighbors, including the Hungarians and Byzantines, following their defeat and subsequent disappearance in 1091. They were an essential link in the chain of steppe powers that dominated Eastern Europe for centuries.

Magyars: From Steppe Raiders to Kingdom Founders

Era: 9th – 10th centuries CE

Region: Ural Mountains → Central Europe

Highlights: Nomadic warriors who invaded Western Europe before settling in Hungary.

Legacy: Founded the Hungarian state and preserved equestrian traditions.

Famous Historical Figures: Árpád, Taksony, Géza

The Magyars were a Uralic-speaking nomadic people. They migrated westward from the steppes near the Ural Mountains in the 9th century CE, forming a confederation of seven tribes. Magyars crossed into the Carpathian Basin around 895 CE, under the leadership of Árpád. The movement is known as the “Hungarian Conquest” in Hungarian history. They quickly expanded their territory, taking advantage of a power vacuum created by weakening Frankish and Bulgar control. Chronicler Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus described them as “fearsome in speed and silence” due to their cavalry skills.

Over the next few decades, they conducted large-scale raids into Germany, Italy, and France, as far west as Burgundy and the Pyrenees. They were decisively defeated by Otto I, the King of East Francia, at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 CE, which marked the end of their western expansion. The Magyars subsequently settled permanently in the Carpathian Basin, where they converted to Christianity under King Stephen I in the early 11th century.

The Magyars transformed from nomadic conquerors to the founders of the Hungarian state, merging steppe military traditions with European feudal structures. Their adaptability and the enduring impact of their state highlight the complex interplay between nomadic and sedentary societies. Hungary would become a significant political player in Central Europe for centuries, its foundation laid by the horsemanship and leadership of the Magyars.

Cumans: The Last Roamers of the Steppe

Era: 10th – 13th centuries CE

Region: Steppe north of the Black Sea

Highlights: Fought Mongols and became key players in Eastern European politics.

Legacy: Integrated into Hungary; influenced cavalry traditions and medieval warfare.

Famous Historical Figures: Köten Khan, Boniak, Sharukan

The Cumans were a Turkic nomadic confederation that rose to prominence in the 10th century CE. Occupying the wide grasslands north of the Black Sea, they shared a close kinship with the Kipchaks and often dominated the Pontic-Caspian Steppe. The chroniclers of Eastern Europe depicted them as “tall, fair-haired warriors with swift horses and sharp arrows”. The Cumans were a highly mobile force and became a scourge of the region. The Rus, Byzantines, and Hungarians were all vulnerable to their raids and frequently encountered them, sometimes as foes and sometimes as allies.

The Cumans allied with the Rus in 1223 to fight the Mongols at the Battle of the Kalka River, which resulted in a complete rout that would foreshadow the Mongols’ eventual arrival. As the Mongols marched westward, many Cumans took flight and were given refuge by the Hungarians under King Béla IV on condition they serve as auxiliaries. Conflict soon arose with the Hungarian nobility, and the Cumans were ultimately assimilated into the country. Some even became part of the royal guard as elite cavalry units into the medieval era.

The Cumans’ independent power as a force would be reduced after the Mongol invasions, but their impact on the political and military history of Eastern Europe was notable. They are still remembered in toponyms, surnames, and medieval military traditions throughout Hungary and the Balkans. The Cumans were among the last of the free-roaming nomadic horse cultures of the western steppe.

Mongols: Masters of the Mounted Empire

Era: 13th – 14th centuries CE

Region: Mongolia → Eurasia

Highlights: Built the largest contiguous empire in history with unmatched cavalry tactics.

Legacy: Revolutionized global warfare, diplomacy, and trade networks.

Famous Historical Figures: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Subotai

The Mongols were a nomadic culture that emerged from the Mongolian steppes in the early 13th century. They were united under the leadership of Temujin, who took the title of Genghis Khan, and created a highly disciplined and mobile cavalry force. The Mongols’ military tactics, based on speed, maneuverability, and ruthless efficiency, allowed them to conquer vast territories, including much of Asia and parts of Europe. “The strength of a wall is neither greater nor less than the courage of the men who defend it,” Genghis Khan is reported to have said, underscoring his contempt for fortifications and his confidence in the power of mobility and morale.

At the height of their power, the Mongols ruled over the largest contiguous land empire in history, spanning from Korea to Hungary. Their conquests, which included the Battle of Kalka River in 1223, the fall of the Khwarazmian Empire, and the sacking of Baghdad in 1258 under Hulagu Khan, were characterized by their ability to decimate armies several times their size through the use of mounted archery, psychological warfare, and an extensive network of spies and scouts. Despite the empire’s eventual fragmentation into various Mongol khanates by the late 13th century, the Mongols’ influence continued to be felt for many generations.

The Mongols had a profound and lasting impact on the world. Their conquests and rule ushered in a new era of cross-continental trade, the spread of technologies and ideas, and an unprecedented connection between Europe and Asia. The legacy of the Mongols is seen in the successor states and dynasties that emerged from the empire, such as the Yuan dynasty in China and the Ilkhanate in Persia. The Mongols are the most renowned and transformative of all nomadic horse cultures.

Golden Horde / Tatars: Mongol Legacy on the Western Steppe

Era: 13th – 15th centuries CE

Region: Russian Steppe

Highlights: Mongol successor state that ruled much of Eastern Europe and Russia.

Legacy: Deep impact on Russian military, trade, and taxation systems.

Famous Historical Figures: Batu Khan, Berke Khan, Öz Beg

The Golden Horde was a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate founded in the mid-13th century by Batu Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan, as a result of the Mongol invasion of Eastern Europe. After the successful campaign against Kievan Rus’ and the heavy Battle of the Kalka River in 1223, the Horde’s influence would preside over most of the steppes of today’s Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan as they were described by the Russian annals as “the yoke from the East” for the next two centuries.

Administering a highly developed tribute and indirect rule system, they maintained a steady grip on subject principalities while allowing a large amount of autonomy as long as their allegiances and payments were kept. As an example of their current strength, the Mongols under Batu’s command achieved a great victory over the combined Hungarian and Polish forces at the Battle of Mohi (1241).

The Horde eventually fragmented into smaller khanates, including Kazan and Crimea, in the face of the growing power of the Grand Duchy of Moscow and internecine rivalries. The political, military, and diplomatic legacy of the Horde on Russia was long and significant as it changed the core of Russian governmental and military organization, as well as diplomatic apparatus. The ethnonyms “Tatar” became widely generalized as referring to the descendants of the Horde.

Furthermore, many steppe traditions remained well into the future. The Golden Horde inherited the Mongol military and administrative organization.

Timurids: The Sword and the Scholar

Era: 14th – 15th centuries CE

Region: Central Asia and Persia

Highlights: Founded by Timur (Tamerlane), known for brutal conquest and cultural patronage.

Legacy: Blended Mongol militarism with Persian intellectual and artistic excellence.

Famous Historical Figures: Timur, Ulugh Beg, Shah Rukh

The Timurids first appeared in the late 14th century, led by Timur (1336–1405), known as Tamerlane. Claiming to be a son-in-law and member of Genghis Khan’s tribe, they began their rise in Transoxiana. Timur established his empire through invasions of Persia, India, Central Asia, and the Middle East, known for his military prowess and his ability to inspire fear in his enemies. A steppe nomad with imperial aspirations, Timur combined the mobile cavalry tactics of the Mongols with an administration and statecraft that he adopted from the peoples he subjugated. “Where I pass, the grass will never grow again,” Timur famously said, boasting of the devastation he caused during his campaigns.

His most significant victory was at the Battle of Ankara in 1402, when Timur captured and executed the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I, temporarily halting Ottoman expansion. Timur’s empire stretched from Delhi to Baghdad and Damascus. Timur was also known for his cultural patronage, initiating the Timurid Renaissance, a time of outstanding achievement in architecture, science, and the arts that influenced Persian and Islamic culture for generations.

After Timur died in 1405, the empire eventually broke up as his successors struggled for power, but his influence continued through the Timurid Renaissance and in his great-great-grandson, Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire in India. The Timurids represent one of the rare cases in which the characteristics of the nomads were combined with cultural development to remain among history’s most powerful horseborne empires.

Turcomans: From Steppe Riders to Empire Builders

Era: 11th century – onward

Region: Central Asia → Middle East

Highlights: Nomadic horsemen who formed powerful Islamic empires.

Legacy: Laid the foundations for modern-day Turkey and Iran’s Islamic military traditions.

Famous Historical Figures: Alp Arslan, Tughril Beg, Osman I

The Turcomans were a group of Oghuz Turkic nomads who migrated west from Central Asia from the 10th to 12th centuries, introducing the customs and traditions of the steppe to the Islamic world. The Seljuks, one of the many tribes of the Turcomans, came to dominate the rest of the Turcomans in the 11th century. After the defeat of the Byzantine army at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, they opened Anatolia to Turkic settlement.

According to one Seljuk chronicler, the tribe’s rise to power was a result of “the will of the heavens riding on the backs of horses,” a reference to the ancient Iranian tradition of divine kingship and their military superiority. They formed a large empire across Persia and the Middle East on the back of their mounted archers and the use of ghulams (slave-soldiers) disciplined and trained in the Persian model.

With the collapse of Seljuk power, small Turcoman beyliks began to emerge in Anatolia, one of which was the Ottoman Empire. A state that would eventually rise to great power in the late 13th century. Under the leadership of Osman I and his successors, the Ottomans began to expand their territory, conquering much of Anatolia and the Balkans through the use of nomadic cavalry tactics combined with siege technology and an efficient, centralized administration.

After the capture of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II, the empire transitioned from a nomadic warrior state to a global empire. However, the early Ottomans, who conquered Constantinople and established their dynasty, were of Turcoman nomadic origins and maintained a Turcoman cavalry culture within their army and border society.

The Seljuks and early Ottomans showed the potential for long-lasting state structures based on the culture and lifestyle of the nomadic horsemen, while retaining many of their traditional elements of mobility, archery, and tribal identity while also adjusting to the role of Islamic imperial warriors.

Kazakhs & Kyrgyz: Guardians of the Steppe Spirit

Era: Post-Mongol era – Present

Region: Central Asia

Highlights: Maintained strong nomadic traditions and horse-centered lifestyles; still celebrate equestrian sports.

Legacy: Preserved steppe culture into the modern age; symbolic of nomadic resilience.

Famous Historical Figures: Ablai Khan, Kenesary Khan, Manas (epic hero)

The Kazakhs and Kyrgyz are Central Asian nomadic cultures that crystallized after the dissolution of the Mongol Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. Descendants of Turkic and Mongol steppe-dwelling peoples, they developed strong equestrian traditions. Herding, archery, and mobility were central to their way of life. The Kazakhs organized into tribal confederations, or “Zhuz,” while the Kyrgyz populated the high mountain pastures of the Tien Shan region. Oral epics, such as the Manas, recount histories of resistance and pride.

Politically, these groups were significant in regional power dynamics. The Kazakhs, under leaders like Ablai Khan, employed guerrilla tactics and strategic diplomacy to resist Russian expansion in the 18th century. The Kyrgyz similarly resisted Qing and subsequently Russian control, fiercely defending their mountainous territories. Although both were eventually incorporated into the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union, they retained their nomadic cultures longer than other steppe peoples. In the modern era, equestrian sports such as kokpar and traditional horsemanship remain a vital part of the Kazakh and Kyrgyz national identities.

Plains Tribes of North America: Riders of the Buffalo Nations

Era: 17th – 19th centuries CE

Region: North American Great Plains

Highlights: Transformed by the horse; revolutionized buffalo hunting, warfare, and mobility.

Legacy: Created one of the most iconic horse cultures in the Americas.

Famous Historical Figures: Sitting Bull, Chief Joseph, Crazy Horse

Life changed rapidly for the Plains Indians of North America with the introduction of the horse in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Spanish first supplied horses to the North American Plains tribes. Tribes as diverse as the Sioux, Cheyenne, Blackfoot, and Nez Perce quickly adopted riding, with horses radically transforming their hunting, warfare, and mobility. The horse enabled the tribes to effectively pursue the massive buffalo herds of the plains, transforming previously sedentary or semi-nomadic cultures into true horse cultures, as expressed in the Lakota phrase, “The horse made us a nation again.”

As they became fierce defenders of their way of life as the U.S. pushed westward, the Sioux defeated Custer and his men in the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, and the Nez Perce managed a strategic retreat of 1,200 miles while pursued by the U.S. Army in 1877, among their most brilliant maneuvers. Although all these horse cultures would eventually be subdued in federal campaigns and sent to reservations, their spirit of independence and rich cultural traditions continue in modern powwows and equestrian preservation.

Comanche: Lords of the Southern Plains

Era: 18th – 19th centuries CE

Region: Southern Great Plains, U.S.

Highlights: Once called the “Lords of the Plains,” they mastered horsemanship after acquiring horses from the Spanish.

Legacy: Dominated the region and resisted colonization longer than most Indigenous nations.

Famous Historical Figures: Quanah Parker, Ten Bears, Iron Jacket

Emerging from the Shoshone in the late 1600s, the Comanche went from a relatively minor people to an empire. Early Shoshone bands that had moved onto the Southern Plains by the 18th century received horses from the Spanish. A few generations later, the Comanche developed an equestrian culture unrivaled by any other people. So great was their horsemanship that Spanish colonists began referring to them by a unique term: the “Comanchería.” This name came to encompass an immense swath of territory that the Comanche had carved for themselves through movement, diplomacy, and conquest. “Their mastery of the horse was like nothing we had ever seen,” one settler later recalled, “man and animal moved as one.”

It was the extent of their power that distinguished the Comanche from other tribes of the Plains. They hunted, raided, created, and navigated vast trade networks; they also dictated regional politics, defended their territory, and negotiated with European powers as equals. The Comanche were fierce warriors who defeated Spanish, Mexican, and American military forces in battle. They also successfully resisted the settlement of Texas for much of the 19th century, with Quanah Parker, the last Comanche war chief, becoming a national symbol of both resistance and accommodation.

While most Indigenous people were driven off their lands in the 19th century, the Comanche remained a dominant force in the region for nearly two hundred years. The Comanches were one of the most strategically important and fiercely independent nomadic horse cultures in world history.

The Legacy of These Nomadic Horse Cultures

Twenty nomadic horse cultures that lived lifestyles that eventually shaped modern nations, showing that history was not only built in cities, nor etched in stone, but also galloped across plains, blew across steppes, and thundered down mountain passes. From the Scythians to the Comanche, each of these cultures harnessed the power of the horse not just as a weapon of war, but as a means of living—redrawing maps, toppling empires, and galloping into the modern age to leave a legacy that still echoes in identities and traditions today.

While many of these cultures eventually became sedentary, assimilated, or displaced, their impact was felt in military tactics, political structures, and collective memory. Their mobility, adaptability, and connection to the natural world serve as a reminder that power can be ephemeral—and that some of history’s most influential civilizations left no pyramids, only hoofprints.