How the Spanish Civil War Reshaped Europe on the Eve of WWII

A War That Was Never Just Spanish

Between 1936 and 1939, the Spanish Civil War was fought between a democratically elected Republican government and an authoritarian Nationalist Rebellion. Yet the Spanish conflict became so much more than that. From the bombing of cities and civilian populations to the wholesale slaughter of political opponents, Spain would serve as proof of how future wars would be fought. As one contemporary commentator noted, Spain had become “a battlefield of ideas as much as armies.”

Spain provided a tremendous shock to observers worldwide. Fascist leaders, communist politicians, and struggling democrats anxiously viewed Spain as the proving ground for their own ideologies. Germany and Italy rushed aid in the form of planes and troops. The Soviets would follow suit by backing the other side. Britain and France did nothing, appeasing in the hopes that neutrality would stave off another European war. Spain proved how empty that desire for peace would become.

The Spanish Civil War was a political, military, and moral battleground that helped reshape Europe. New weapons would be tested. Ideologies would become hardened. And world leaders would learn just how costly it is to do nothing. Before 1939, Spain had already offered a preview of the world war to come—and how truly unprepared the world was.

Europe in Crisis During the 1930s

Europe began the 1930s in the economic turmoil of the Great Depression. High unemployment, falling trade, and deflationary austerity measures contributed to a widespread loss of confidence in European governments. People were angry and scared both in urban centers and rural communities. Liberal democracy seemed incapable of delivering stability or security. Political extremists on both the left and right promised order and dignity, appealing to nationalist sentiment.

Fear was used to justify authoritarian philosophies like fascism and communism. Fascists targeted minorities for the problems they claimed were faced by everyone. Communist rhetoric declared that the bourgeoisie was conspiring against the working class. Ideologues promised swift and decisive action to return their countries to greatness. Violence was glorified, compromises derided as cowardice, and propaganda touted as the solution to weak leadership. Society became increasingly polarized, with those on either side convinced they would not survive unless they won absolute victory.

Weak democracies found their politicians frequently deadlocked in parliamentary coalitions or crippled by ongoing crises. Many seemed reluctant to take bold action, fearing it would trigger unrest or incite revolution. To some, the descent of into the Spanish Civil War was merely proof of what would happen if the continent’s problems went unaddressed. The economic crisis, reactionary movements, and weak institutions combined to have a devastating effect in Spain.

The Spanish Civil War did not occur in a vacuum; it was the result of Europe’s continued instability. No country sent armies to Spain out of mere curiosity, nor did they observe from a distance. Spain was where Europe’s problems played out in violence and murder. If Europe had been stable, there would be no Spanish Civil War. But Europe was far from stable, and as such, could not escape its impact.

Spain as an Ideological Battleground

The Spanish Civil War began in 1936 as a conflict between forces that supported two competing visions for Spain’s future and, by extension, Europe’s. The democratically elected Second Spanish Republic represented an unstable democracy championed by an informal alliance of socialists, communists, liberals, and anarchists. Though often bitterly divided among themselves, these groups were united in their belief that Spain could and should leave behind monarchy, clerical influence, and privilege.

Ideologically, the Republicans were hardly unified. Anarchist militias wanted a stateless revolution. Communists pushed centralized authority and discipline. Socialists demanded labor rights and land redistribution. Meanwhile, regional nationalist groups fought for independence. George Orwell fought alongside Republican troops. He found Spain was “a country in which, for the time being, the very concept of democracy seemed to be on trial.” Coordination was difficult due to internal divisions. However, these divisions demonstrated how invested ordinary citizens were in fighting a war that could remake society.

Against them stood a coalition of Nationalist forces held together less by ideology than by common foes. Monarchists, conservative Catholics, army officers, and fascists united behind slogans of order, hierarchy, and tradition. Fascist movements like the Falange Española preached authoritarian nationalism based on Italy and Germany. They viewed the Republic as disorderly, atheistic, and degenerate. The Nationalists thus portrayed their struggle as a crusade to save Spain from revolution.

Spain, therefore, represented a microcosm of Europe. Volunteers went to fight for the Republicans because they viewed their fight as one against fascism. The Nationalists were aided militarily and financially by Nazi Germany and Italy, which deployed combat troops, aircraft, and shipped arms. The Republic heavily relied upon the Soviet Union for support.

The conflict showed how ideology could trump nationality. Foreign nations safely tested weapons, tactics, and propaganda in Spain, while staying out of trouble abroad. Bomb raids, political repression, and mass murder previewed World War II. Spain wasn’t just embroiled in a civil war. It had become ground zero for Europe’s future nightmare.

Spain became a place where Europe fought out its ideological differences. By making the Spanish Civil War an international conflict, they changed a domestic war into a prophecy of what was to come. Compromise between the factions had failed. Europe now witnessed its future: democracy against dictatorship; reform against reaction; ideology armed with weapons. What happened there changed Spain’s future; it changed Europe’s future, towards World War.

Foreign Intervention and the Breakdown of Neutrality

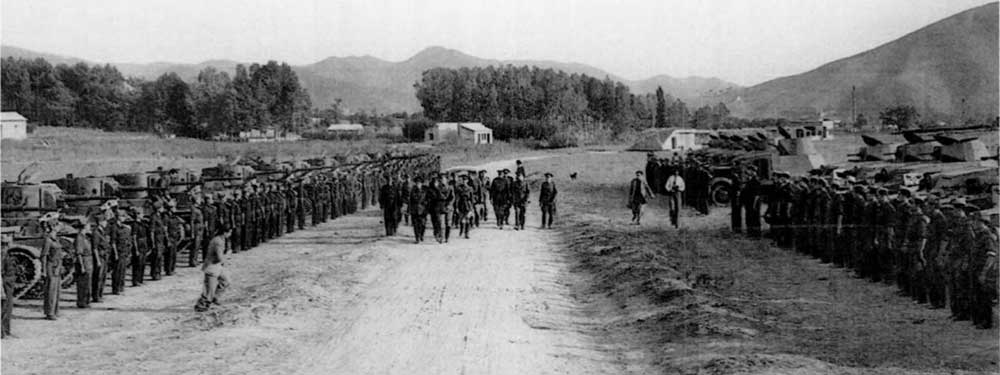

As early as the first weeks of the Spanish Civil War, external powers asserted their neutrality even as they began to intervene. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy contributed men, material, and know-how directly to Francisco Franco’s Nationalist cause. The Spanish Civil War began to transcend the definition of a civil war.

German assistance was steady and significant. Military advisers and elite units arrived early and armed the Nationalists with the most modern technology, boosting their confidence in their operational capacity. Berlin had no obligation or official alliance with Franco; its support stemmed from shared beliefs and interests. But German interference helped tip the scales in their favor. Spain became a conflict where the resolve of outside powers counted just as much as that of those fighting within.

Italy went even further. Mussolini sent massive contingents of men and equipment, including tanks and planes. Italian troops engaged unashamedly in many campaigns, closely associating the Nationalist cause with fascism in Europe on both symbolic and material levels. Wherever intervention succeeded, Italian manpower and materiel kept it going and squeezed the Republic.

The Republic received most of its aid from the Soviet Union. Arms and technicians were sent, although aid was conditional on politics. Communists backed by Moscow infiltrated Republican organizations, which angered anarchists and moderate socialist leaders. As George Orwell pointed out, there was mutual suspicion among members of the Republican side, which harmed co-operation.

On the other hand, the United Kingdom and France decided to play it safe. The governments of both countries supported non-intervention, seeking to limit the conflict and prevent its spread. The Non-Intervention Committee institutionalized this policy by banning arms deliveries and official assistance to the elected government in Spain.

In application neutrality was mixed. Britain and France shied away from the conflict, whereas Germany and Italy offered unabashed support. The imbalance crippled the Republic at a time when it garnered sympathy abroad. Neutrality failed to calm the war and instead bent it to those breaking the rules.

By the end of the conflict, talk of non-intervention seemed meaningless. The intervention had affected the course of events, demonstrating both diplomatic boundaries and how quickly European nations could find themselves embroiled in war without official declarations. Spain’s civil war demonstrated that neutrality on paper and events moving rapidly in the opposite direction were not mutually exclusive.

Military Lessons That Shaped World War II

The Spanish Civil War was quickly becoming a proving ground for modern warfare. Thousands of military officers from nations across Europe watched closely as those lessons unfolded in real-time across Spain. There, they discovered things that could not be taught in traditional military schools. New technologies were used in concert to develop novel tactics and brutal strategies.

Wars are painful learning experiences, and Spain was no different. But here lessons were learned not just by Spaniards but by foreign powers that would soon go to war against one another. As one foreign observer put it, Spain was “a school for war.”

Air power would reach decisive roles that civilians could only imagine. Nazi Germany’s Luftwaffe expeditionary force, Condor Legion, flattened the Spanish town of Guernica with a bombing run in 1937. Operating in support of Francisco Franco’s Nationalists, the Condor Legion unleashed everything from high-explosive bombs to incendiaries on the ancient town. The attack demonstrated the ability of airpower to strike far behind enemy lines to undermine civilian morale.

Guernica taught that terror bombing was not collateral damage; it was now part of a cohesive military strategy. The Condor Legion would improve terror bombing tactics throughout Spain. Testing everything from flight patterns to coordination with ground forces, Luftwaffe intelligence reports were shared through military advisors back in Germany. Reports confirmed what many had suspected: terror from the sky was far more effective at suppressing resistance than traditional attacks.

Close air support would become crucial to modern land offensives. Aircraft were used to interdict enemy defense positions, communications, and transportation routes while ground forces advanced. Ground attacks could now be faster and more flexible than ever before with the use of airplanes. War would now be won with speed and synergy instead of walls and trenches.

Tanks and mechanized infantry would enable armies to fight with increased mobility. Armored and motorized units pummeled enemy positions by punching through enemy lines and crushing anything that remained. While forces on both sides of the war lacked adequate equipment, commanders learned valuable lessons in defeating enemies who remained in place. War would be won with momentum, agility, and mass.

The Spanish Civil War saw the implementation of combined arms warfare. No longer would infantry, armor, artillery, and aircraft act as independent units. Each would act as a crucial component of a larger system. Success or failure would depend on the ability of forces to strike at the right time and communicate with each other. Spain showed what happened when militaries continued to operate in isolation from one another.

Information warfare and psychological warfare would be used to amplify terror and destruction. Bombings, massacres, and propaganda were no longer just military actions but also used to terrorize civilian populations into surrender. Terrorism was used to demonstrate that further resistance was futile. “Fear traveled faster than armies,” one Republican witness wrote.

There was no longer such a thing as non-combatants or lines to be held. Underbelly of cities, roads, farms, and marketplaces all became just as much a target as a military facility. There was no front line, for the entire country had become a battlefield. Spain proved that if another modern war were to break out, it would not be limited in any way.

When the Spanish Civil War ended, military officers from around Europe left with notebooks full of new information. By the time World War II began, many of these techniques had already been tested in battle during the Spanish Civil War.

The Failure of Appeasement and Democratic Resolve

Spain’s Civil War tested the extent of Europe’s commitment to democratic ideals. Violence mounted, and Britain and France decided not to risk further escalation. They thought peace would be maintained if they simply accepted aggression. Provided it was labeled a domestic affair, Europe would allow it. Spain served as a proving ground for guns and political will.

Hitler and Mussolini saw what happened when they intervened in Spain and drew conclusions. Non-intervention emboldened them – every armament train or convoy carrying soldiers, planes, or munitions that reached Spain without response only strengthened their view that the democracies of Europe had neither the will nor the courage to stop them. After the conflict, Hitler noted that ‘whenever one of us stuck his neck out, and the other democracies kept quiet, he was right’. Mussolini drew similar conclusions.

They also developed expectations. Authoritarian governments began to believe that there were no serious repercussions for breaking treaties or openly reneging on public promises, as long as it was done with sufficient stealth. Diplomatic words and reality began to drift further apart. The failure of the democratic nations to make good on their rhetoric in Spain allowed dictators to take risks in other countries.

Support for collective security weakened as international organizations proved powerless to prevent or stop the war. Small countries realized that, in Spain, no one came to their aid when they were threatened, in violation of the promise of collective security.

There was nothing comparable for the Republicans. The Nationalists received a steady supply of aid from abroad, while the Spanish Republic had to play by international rules selectively applied.

This ultimately weakened public support for democratic governments. Those who witnessed the war up close returned home disillusioned. Journalists sent their stories, and academics and volunteers returned from Spain. Many of these people, including the likes of George Orwell, wrote of Spain teaching them ‘the cynical indifference of the democratic powers’.

Disunity between democracies grew. There was more fear of war than unity against aggression, and restraint began to trump morality. Every atrocity committed in Spain was followed by another concession.

The lesson of Spain in 1939 was clear. Appeasement didn’t maintain peace; it merely kicked the can down the road while the dictators grew stronger.

Refugees, Repression, and the Human Cost

The Spanish Civil War created Europe’s first large-scale modern refugee crisis. Thousands became refugees as different fronts moved and cities fell throughout the war. Total estimates range as high as half a million Spaniards who crossed into France alone by the war’s end in 1939. Many refugees entered France exhausted, injured, and starving. Temporary camps along the French coast housed hungry, sick refugees as they awaited uncertain futures. Families became displaced people almost overnight.

Refugees faced repression even after escaping Spain. Rather than sympathy for their plight, refugees were met with suspicion for their political beliefs. French officials interred thousands of Spanish Republicans in barbed-wire enclosures, fearing political revolt among the destitute population. “Freedom without dignity” was how one refugee described exile.

Civil war victory did not result in compromise, but in punitive repression. Republican survivors were executed, imprisoned, or forced to abandon their political beliefs. Families fought to suppress memories, willing themselves to forget names, faces, and public gatherings. Silence became a means of survival.

Political exile had widespread effects on Europe’s intellectual class. Teachers, writers, artists, and labor leaders found themselves spanning France, Mexico, the Soviet Union, and across Latin America. Some hoped to spark future revolution; others hoped to forget trauma. But for many, the Spanish Civil War exile convinced them that negotiation with fascist forces was not possible.

Spain became a lesson for countries that took in refugees. Refugee crises damaged economies and inflamed political tensions. Some doubled down on conservative instincts out of fear of chaos; others felt new moral clarity about standing up to fascism.

Millions would carry the intimate costs of war for generations after 1939. Children grew up wondering about parents lost in the shuffle. Adolescence was spent in refugee camps. Families passed down silence as a survival technique.

European citizens experienced a loss of faith in their governments’ ability to protect them. Spain exposed how fascism could make millions homeless, and how quickly international political strife could turn into a mass humanitarian crisis. Europe learned that lesson on the eve of World War II. They would fail to prevent it from happening again.

Spain’s Outcome and Europe’s Future

Franco won this war through unity of command, sustained foreign intervention, and attrition. Republican leaders splintered over ideology while Franco maintained control of messaging and war aims. Foreign intervention ensured that the nationalists would have air superiority, logistical capacity, and seasoned troops. By 1939, there would be no sweeping victory—only grinding pressure toward the status quo imbalance.

Franco ruled Spain until his death in 1975, establishing one of Europe’s longest dictatorships. Political opponents were silenced through censorship, repression, and imprisonment. Franco framed his victory as Spain’s deliverance from savagery. To conquer Spain, it felt more like silence and fear.

On the outside, Spain was left impoverished and politically isolated. Though never entering the war, Spain’s fascist sympathies left it diplomatically ostracized in 1945. The country was shut out of the Marshall Plan and denied membership in burgeoning European organizations. Starved of investment and opportunity, Spain remained firmly detached from the continent.

Cold War geopolitics changed this. Spain moved away from fascism and towards strategic importance. Francoist Spain was begrudgingly reintegrated for the sake of anticommunism stance. Western powers signed military agreements with Spain and provided limited economic support. But democratic Spain would have to wait for fuller European integration while it was stuck under authoritarian rule.

Franco’s victory sent a powerful signal to dictators across Europe. Authoritarianism could seize power through violence. International protest could be weathered so long as a dictator promised geographic neutrality. To interested fascist leaders, Spain was a success story.

Democratic leaders learned less from the Spanish Civil War. The inability to aid the Spanish Republic was not for lack of desire—but rather fear and caution. World leaders preached peace; autocrats recognized apathy. Hitler supposedly said that the “democracies had lost their nerve”. Spain proved him right.

Spain also proved how wars could change the map without redrawing borders. While treaty lines held, the European balance of power had shifted. Authoritarianism had survived a war of attrition with democracy. Spain was a warning of what was to come.

By 1939, Europe had gotten a preview of what fascism could do. Europe had seen an authoritarian government installed by the barrel of a gun. But what Europe learned from this would never be enough. What it didn’t learn would kill millions.

Spain as the Warning Europe Ignored

The Spanish Civil War determined the future of Europe long before World War II began. It revealed how precarious peace had become and how rapidly ideological violence could erupt and spread beyond national boundaries. Spain did not fall alone; rather, it was a warning that large-scale dangers were massing in Europe. Europe watched a democracy crumble from constant pressure and saw lessons that they would soon regret not learning.

It was both a moral trial and a dry run. Fascists were prepared to do whatever was necessary to win. Liberals feared doing what was necessary. The war exposed the potential for foreign subversion, propaganda, and terror to become deciding factors. Madrid showed how quickly a balance of wills could be outweighed by a balance of fear. Authoritarian aggression met democratic caution head-on. Spain was where Europe’s tomorrow went to fight for a fleeting moment.

To many people watching from abroad, Spain was an open rehearsal. Reporters, aid workers, and refugees smuggled tales home of what could happen if fascism were allowed free rein. But warnings were diluted through distance and disbelief. Spain’s agony was decried but seldom met with action. The belief that restraint would pave the way to peace was massively optimistic and proved to be dead wrong.

Spain was an opportunity lost. The war demonstrated what was on the line, what horrors were possible, how high prices could climb, and how easily violence could become accepted. Europe’s inaction did not start the next war, but it did reduce the inhibitions against it. When the world would eventually catch aflame, many of the warning signs were there—in Spain, they were seen and dismissed.

![[Video] Fascinating World War 2 History Facts](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-11-at-7.17.46 PM.jpg)

![[VIDEO] How Fur Farms, World War II, and a Bomb Created Germany’s Raccoon Invasion](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Screenshot-2025-07-07-at-1.57.45 PM-768x512.jpg)