Cutting Edge: The Tale of Galvarino’s Knife-Handed Battle

GGalvarino, a native Mapuche warrior, is known for surviving severe injuries and for leading his people in resistance against the Spanish conquistadors. The story of Galvarino takes place during the Arauco War of the 16th century, a conflict between the indigenous Mapuche people and Spanish invaders in what is now Chile.

After being captured and having his hands amputated by the Spanish as punishment, Galvarino turned his misfortune into a symbol of resistance by attaching knives to his arms and returning to battle. His remarkable story of resilience, leadership, and bravery has since become a powerful symbol of the broader struggle for indigenous rights and autonomy.

Galvarino’s Early Life & the Mapuche

Relatively little is known of Galvarino’s early years before he struggled with the Spanish. Historical records are sparse on details of his upbringing, but we do know that he was a Mapuche warrior long before the Spanish had arrived in South America. As with his compatriots, he would have been educated in the ways of war from an early age. The Mapuche were a fierce and powerful people long before the Spanish conquest. They were considered among the most successful and dominant of the native tribes in the area.

Mapuche society was centered on small family clusters, or lineages, known as ‘Lofs’, each with a chief, a ‘Lonko’. The Mapuche were never as highly centralized as many other societies in the area. However, there was a tradition of militarism, and the Mapuche could be mobilized quickly, under the command of a military leader called a ‘Toqui’, who was appointed for the duration of a specific conflict.

Mapuche is a word that means ‘people of the land’. The Mapuche have a long and distinct history in the areas of modern-day Chile and Argentina, having lived there for thousands of years. During this time, the Mapuche developed their own unique culture, language, and social systems. Agriculture was the primary mode of subsistence for the Mapuche, though they also hunted and gathered as needed. Despite being agriculturalists, the Mapuche were also semi-nomadic, moving their communities with the seasons. This helped them to take advantage of the best resources as they became available. It also gave them a deep, intimate knowledge of the terrain, which would later serve them well in the wars to come.

The Mapuche also had their own spiritual and cosmological beliefs. At the center of Mapuche religion was the notion of a dualistic conflict between forces of good and evil. A multitude of gods and spirits populated the Mapuche spiritual world. At the top of this hierarchy was the supreme Mapuche god, Ngenechen. The Mapuche also had an active tradition of ancestor worship. The Mapuche believed in a group of spiritual leaders called ‘Machi’, who were shamans that had a unique and essential role in Mapuche culture.

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the Mapuche people had also faced foreign invaders in the form of the Incas. In the late 15th century, the Inca Empire had expanded its territory north of the Mapuche, and they began trying to conquer Mapuche territory as well. The Inca were ultimately unsuccessful, however, and the Mapuche were able to resist and remain independent.

The Mapuche first encountered the Spanish in 1536, when an expedition led by Diego de Almagro passed through Mapuche territory. The initial interaction between the Mapuche and the Spanish was amiable enough, but as the Spanish began to colonize the area in earnest, problems emerged between the two groups. The Spanish were interested in finding gold and other resources in the area, which led them to encroach on Mapuche land, sparking open conflict between the Mapuche and the Spanish. This led to the Arauco War, a series of conflicts that would last over 300 years.

The Fateful Battle of Lagunillas

Expecting a Spanish invasion, the Mapuche prepared to face them by positioning their war bands in 3 separate locations: a pucará on Andalicán height, south of Concepcion, controlling the coast of Arauco, while the rest of the army was nearby, between Millarapue and Tucapel. On October 29, Governor García Hurtado de Mendoza’s well-supplied army left Concepcion and proceeded south towards the Bio-Bio River. He sent a small advance party upstream to cut wood and make rafts. This diversion also had the advantage of keeping the Mapuche army in the Andalicán area.

At the same time, Mendoza used small boats and rafts of his own construction to transport his thousand horses across the river. The ruse worked, and he managed to bring his whole army across the river, unopposed at the river’s mouth.

On reaching the southern side, Mendoza marched a league further south to some shallow lakes in the foothills of the Nahuelbuta Range in Araucanía. He set up camp there and sent a small cavalry patrol south under Captain Reinoso to reconnoitre the ground for the next day’s march. Reinoso’s force came into contact with the Mapuche army on Andalicán and was attacked, forcing the Captain to fall back. He managed to send word to Mendoza that a large Mapuche force was advancing against him.

Around this time, two Spanish soldiers who had left the camp without permission to go and fetch some fruit were surprised by a large Mapuche force lying in wait. One soldier was killed, but the other escaped and raised the alarm in camp.

On receiving the warning from Captain Reinoso, Governor Mendoza sent a reinforcement of fifty cavalry and twenty arquebusiers under Rodrigo de Quiroga to help slow the Mapuche advance through a series of marshes and ponds. On receiving news of the ambush, Mendoza issued a quick order to engage and repulsed the Mapuches’ first attack. Almost at once, Reinoso and Quiroga returned with their forces to the main army, the Mapuche army from Andalicán close on their heels, and the engagement became general.

Armies of around 5,000 warriors were not uncommon at the time, and so although outnumbered, the Spanish army had the advantage of the arquebuses and artillery to disrupt the Mapuche attacks, while the cavalry could be used to take advantage of the ensuing confusion to break the Mapuche and force them back into a marsh for cover from the horsemen.

The Spanish infantry pursued the enemy into the marsh and, after a determined stand, the Mapuche were forced to retreat into the wooded hills that backed the marsh. The Spaniards pursued, but cautiously, as ambushes were common, and returned in the late afternoon with prisoners. Two Spaniards were killed, and many more were wounded, but so many were seriously wounded that the engagement could not be pursued further. Mapuche losses numbered 300 dead and 150 prisoners, including Galvarino.

As punishment for the insurrection, Mendoza ordered the right hand and nose of some of the prisoners to be amputated, while others (Galvarino included) had both hands cut off. The prisoners were then released as both a lesson and a warning to the rest of the Mapuche.

Mendoza sent him to inform General Caupolicán (leader of the Mapuche forces) of the quality and number of Spanish troops that had again entered Mapuche land. It was all about psychological warfare and intimidation, and that the Spanish were not to be trifled with. Punishment was swift and decisive, and the best form of control was to intimidate into submission.

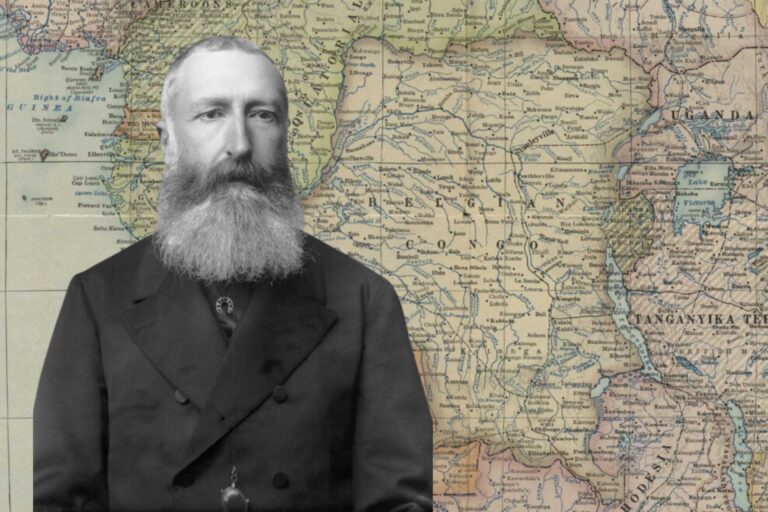

Governor García Hurtado de Mendoza was a battle-hardened military veteran sent by King Philip II of Spain to put down the Mapuche rising. His methods were at times ruthless and unsympathetic, as shown in his punishment of Galvarino and the captured Mapuche warriors. In this way, he hoped to break the spirit of the Mapuche and cow them into submission. In this, Mendoza was to be badly mistaken in the underestimation of the Mapuche, their will, and resistance.

Strengthened Resolve

Galvarino did not bend to the Spanish intimidation and, after the amputation, instead of a message of humiliation, he returned to his people as a soldier full of strength and hope. He had knives tied to the remains of his arms and made a call for arms to his fellow warriors.

Following the brutal amputation of his arms, Galvarino transformed his personal tragedy into a powerful symbol of resistance against Spanish rule. Instead of succumbing to despair, he repurposed his mutilated arms, fastening knives to the stumps. Galvarino’s resilience and determination became a rallying cry for his fellow warriors, as he returned to his people not with a message of surrender but with a call to arms. Galvarino’s transformation of his mutilated arms into a symbol of defiance inspired hope and determination in his fellow warriors.

His example and determination inspired his fellow Mapuche warriors to fight with even greater resolve. Galvarino’s courage and resilience in the face of such a brutal act of Spanish aggression inspired the Mapuche warriors to fight with even greater determination and resolve.

He played an important role in boosting the morale of the Mapuche forces and in rallying them to fight against Spanish oppression. Galvarino encouraged the Mapuche to resist Spanish rule and to fight back with renewed determination and to start a larger campaign against them. Galvarino also referred to the memory of Lautaro, the young Mapuche page who had escaped the Spanish commander Pedro de Valdivia and had taken up arms against him.

Lautaro was a young Mapuche who had become a page to the Spanish commander Pedro de Valdivia and had gained valuable military experience by observing the Spanish tactics while serving under him. However, Lautaro eventually escaped and returned to his people, leading them in their resistance against Spanish rule. He played a key role in the Mapuche resistance by using his knowledge of Spanish tactics to his people’s advantage.

Lautaro’s leadership and military acumen were crucial in shaping the Mapuches’ military strategy during the Spanish invasion, as he anticipated and countered Spanish moves. Galvarino called on the Mapuche to fight the Spanish as Lautaro did, emphasizing the importance of strategic and tactical knowledge in their struggle.

by

AnderTRON

The Mapuche leaders, recognizing Galvarino’s indomitable spirit and the powerful symbol he had become, decided to entrust him with a squadron of warriors that would join the Mapuche chief, Caupolicán, in the upcoming campaign. Caupolicán, the Toqui, or war leader, of the Mapuche forces, was one of the most important Mapuche leaders during the Spanish invasion of Chile. He was known for his strategic leadership and for rallying and organizing Mapuche warriors in their fight against the Spanish.

Galvarino was given command of a squadron that would fight under the overall command of Caupolicán during the upcoming campaign. In addition to his leadership skills. This decision further highlights Galvarino’s importance as a symbol of resistance and his leadership abilities despite his physical limitations.

Galvarino fought in the campaign and proved to be a formidable leader. In addition to serving as a symbol of Mapuche resistance, Galvarino was a skilled and inspiring leader in his own right. He led his squadron with skill and determination, inspiring his fellow warriors to fight with renewed vigor.

Galvarino’s leadership and presence on the battlefield, with knives fastened to his stumps, served as a powerful reminder of the cruelties the Spanish were capable of and the need to fight back with unwavering determination. His story is a testament to the power of symbols and the importance of strategic and tactical knowledge in the fight against oppression.

Battle of Millarapue & The Aftermath

The Battle of Millarapue was a conflict between the Mapuche people and the Spanish invaders led by Governor García Hurtado de Mendoza. The Mapuche, led by their Toqui Caupolicán, had mustered an army of about 20,000 warriors. The Spanish force under Mendoza numbered about 500, and a smaller force of indigenous auxiliaries joined it.

The battle began with the two armies engaging each other in a fierce struggle. The Mapuche, despite being outnumbered, fought bravely and inflicted heavy casualties on the Spanish forces. Galvarino, leading his squadron with knives attached to his arms, fought with incredible courage and determination. He succeeded in killing Mendoza’s second-in-command, a feat that inspired his fellow warriors and prompted the Spanish forces to retreat momentarily. However, the Spanish troops, with their superior weapons and tactics, eventually overpowered the Mapuche.

The Mapuche forces suffered heavy losses during the battle. It is estimated that about 3,000 Mapuche warriors were killed, while the Spanish lost around 40 men, and many more were wounded. The numerical advantage of the Mapuche was insufficient to overcome the Spanish technological and tactical superiority.

After several hours of intense fighting, the Mapuche forces began to retreat, and Galvarino, who had fought with unmatched determination and had inspired his fellow warriors with his bravery, was captured by the Spanish forces during the retreat. His capture marked a turning point in the battle and was a significant blow to the morale of the Mapuche forces.

Galvarino was brought before Mendoza after his capture. Despite the brutal punishment he had already endured and the Mapuche defeat, Galvarino remained defiant. According to some sources, Galvarino was “fed to the dogs”, however, most sources agree that he was sentenced to be hanged. His execution was carried out in front of the remaining Mapuche prisoners as a warning to those who continued to resist Spanish rule.

Galvarino’s death marked the end of a chapter in the Mapuche resistance against Spanish colonization. His bravery, both in the face of brutal punishment and on the battlefield, made him a symbol of resistance for the Mapuche people and an inspiration for future generations. Despite the loss at Millarapue and the execution of one of their most iconic leaders, the Mapuche continued to resist Spanish rule for many years, displaying the same resilience and determination that Galvarino had embodied.

The Mapuche Resistance Survives

The battle of Millarapue wasn’t the end of the Mapuche resistance against the Spanish. Despite the Mapuche having lost one of their iconic leaders (Galvarino included) and suffering many casualties in the battle, the Mapuche population did not back down easily, and new leaders took up the task of organizing further military offensives and rebellions in the coming years.

B.diaz.c, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite this disadvantage, the Mapuche were able to maintain a long resistance, which endured for centuries. This persistent resistance to colonization made the Mapuche one of the few indigenous peoples in the Americas to resist a European colonial power for a long time.