A Brief Introduction to 22 Egyptian Gods

Delving into the Divinity of Egyptian Gods

The Egyptian Gods have long been a subject of fascination for scholars, enthusiasts, and the general public alike. The land of pyramids, the Nile, and mysterious hieroglyphs is also home to a vast pantheon of deities, each with their own stories, characteristics, and areas of influence.

Rich in mythology, with themes of power, love, betrayal, and redemption, it offers a window into how ancient Egyptians understood the world around them and their place in it. Join us as we set out on an exciting journey to discover 22 of the most iconic Egyptian Gods and demystify them, unraveling the mysteries and legends of their fascinating stories.

Ra’s Sun Boat Journey

Ra is the ancient Egyptian Sun God, the god of the sun, who was said to travel across the sky in a sun boat. At dawn, he rose out of the underworld, and at dusk, he set into the underworld. This symbolized the unchanging ideas of life, death, and resurrection. This Egyptian god was often depicted with a falcon’s head, and Ra was said to have created all life.

The Sun was critical in giving life to all things and watching over the ripening of the harvests sown by man. The Egyptians, noticing this, worshiped the sun as a God. The sun, which symbolized life, heat, and growth, was Ra, the creator of the universe and giver of life. As Ra was the creator of the universe and the source of all life, his influence on man was so significant that he became one of the most highly worshiped Gods, even to the point of being considered the Supreme God, the King of Egyptian Gods.

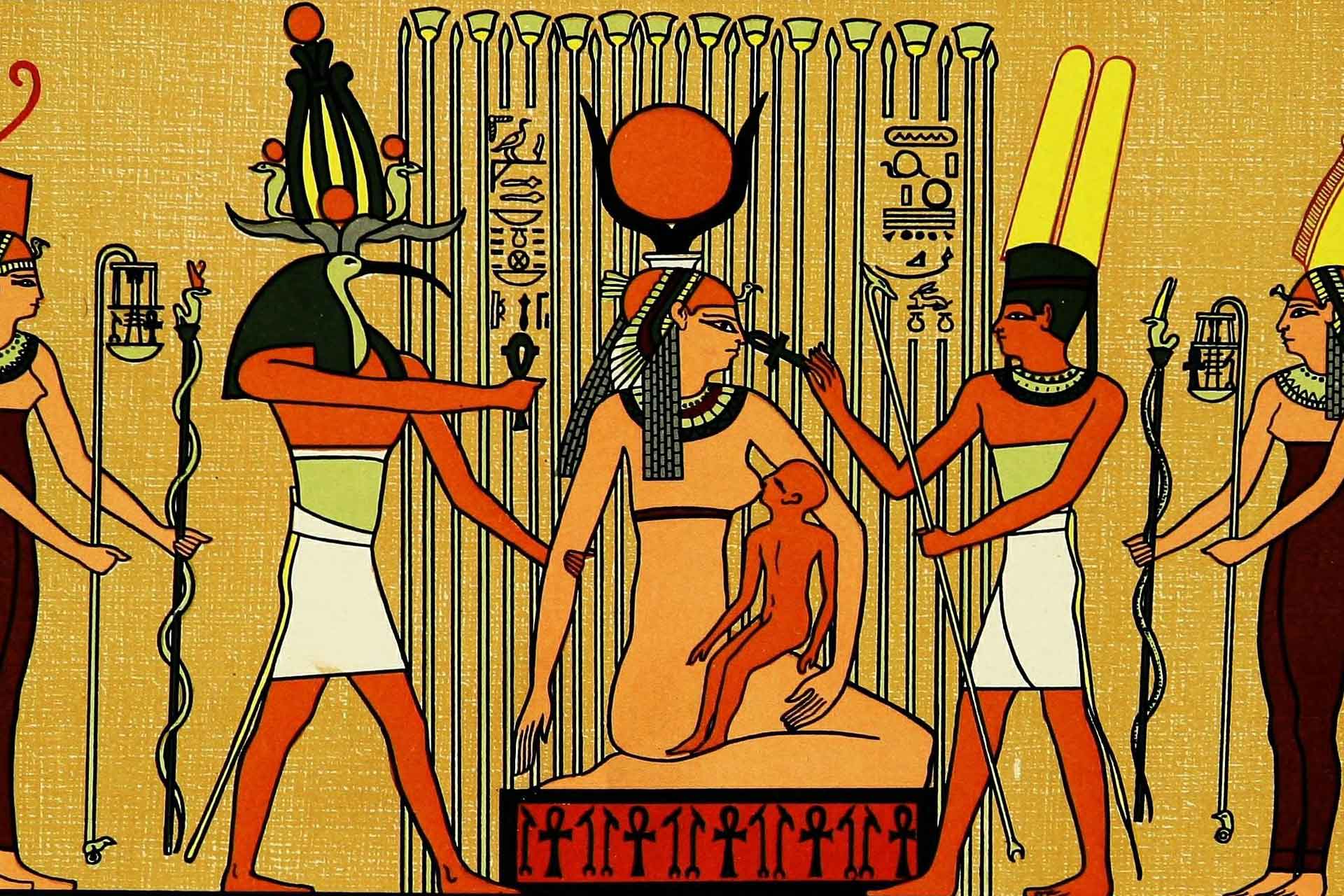

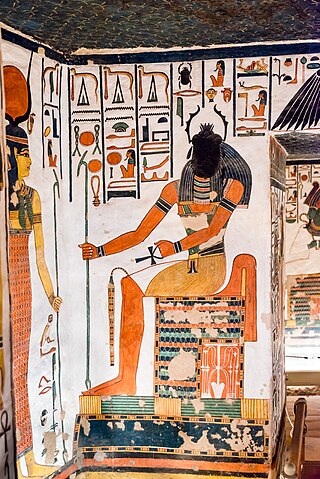

Osiris, the First Mummified Egyptian God

Osiris is usually portrayed as a mummified king. Egyptians believed he was the first person to be mummified, and thus served as the model for Egyptian funerary rites. The myth of his death at the hands of his brother, Set, and his subsequent restoration to life by his wife, Isis, formed the basis of Egyptian ideas about the afterlife. After Osiris’ murder by Set, his wife Isis reassembled his body parts and wrapped them up, allowing him to rise again. The myth of his resurrection is the source of other stories and rituals.

He also returned for a short time and was alive long enough to mate with Isis and father Horus. As Horus’ birth was contingent on the restoration of Osiris to life, he came to represent new beginnings and was considered the vanquisher of Set, the traitor.

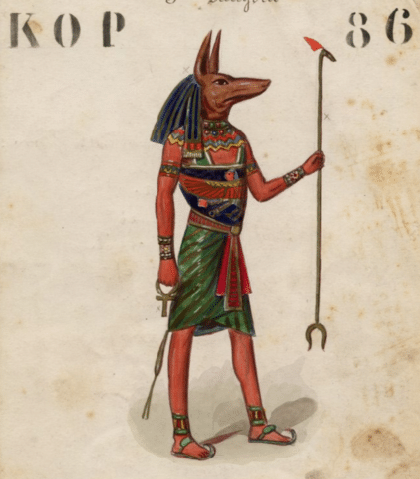

Anubis and the Sacred Scales

The jackal-headed god Anubis was not only the god of mummification. He also presided over the “Weighing of the Heart” ceremony, an essential part of the soul’s journey to the afterlife. In this ceremony, the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of Ma’at to see if it was pure. The Egyptian god that led souls to the underworld, in addition to the god of grave protection, is Anubis.

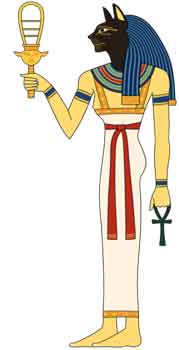

Bastet’s Dual Nature

Ancient Egyptians originally worshipped Bastet as a fierce lioness goddess, but over time she was transformed into a more gentle cat goddess. Bastet eventually came to be associated with domesticity, music, and fertility, in addition to her original domains of warfare. This shift highlights the dynamic and changing nature of ancient Egyptian religious beliefs.

She was the Egyptian goddess of pregnancy and childbirth. It is believed that she was associated with these concepts because domestic cats are fertile.

Bastet was a popular deity whose worship extended to many regions. When Cambyses II of Persia conquered Egypt in 525 BCE, he knew the Egyptian god could be a powerful asset in compelling the Egyptians to surrender. Aware of the Egyptians’ love of animals and their sacred nature in society (especially cats), his soldiers painted images of Bastet on their shields. They then rounded up as many animals as possible and drove them toward Pelusium, a strategically crucial Egyptian city. Afraid that the Egyptians might harm the animals and thus anger Bastet, the Egyptians decided not to risk a battle and surrendered.

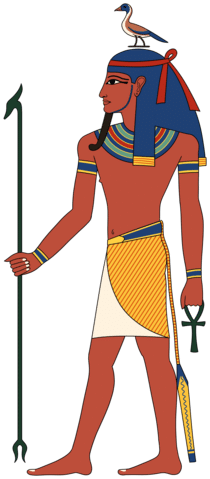

Thoth: The Divine Scribe

Thoth, who has the head of an ibis, is the god of wisdom and writing. He was believed by the ancient Egyptians to be the inventor of hieroglyphic writing. He was also associated with cosmic balance and adjudicated arguments between the gods.

He also maintained the universe along with the Egyptian god Ma’at, as both gods sat on either side of Ra’s solar barque.

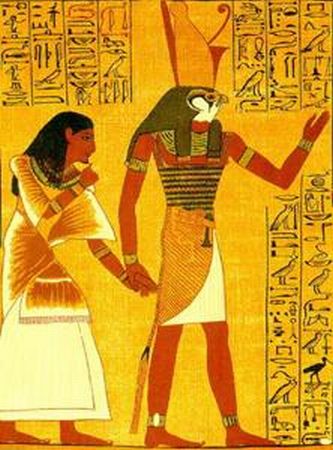

Horus’ Pharaonic Link

The association between Horus and the Egyptian monarchy went hand in hand. Every king was the “Living Horus” who connected the gods to the humans. The fusion between the two gave the winged falcon more significance to the ancient Egyptians.

Taught by his mother, Isis, Horus made it his mission to protect the Egyptian citizens from Set, the desert god who killed his father, Osiris. Horus would engage in many clashes with the evil god, not only to avenge his father’s death but also see who should be the rightful ruler of the Egyptian lands. Afterward, Horus came to be associated with Lower Egypt, becoming the patron and protector of the territory.

The other gods of Egypt had become exhausted after so many years of ceaseless wars and conflict. In an attempt to decide who among them was right, both Horus and Set agreed on a bet. The rulers of the lands agreed to settle their differences by racing each other in boats made of stone.

Right before the race started, however, Horus had a trick up his sleeve. Horus’ boat was actually made of wood and painted to look like stone, while Set’s boat was indeed made of stone and immediately sank because of its weight. Horus became the winner of the bet, becoming the king of Egypt. He made offerings to his deceased father, Osiris, to make sure he lived on as a healthy spirit. Set, on the other hand, was still worshiped as the master of deserts and their hidden springs.

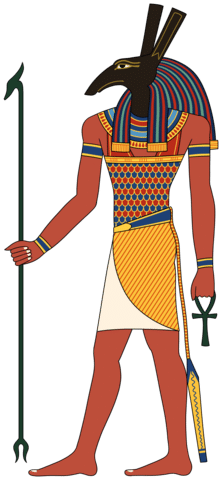

The Mystery of Set

Set was unique, even among the Egyptian pantheon, as he is described as being an entirely unrecognizable beast. He is the embodiment of chaos, violence, storms, and deserts. In many ways, Set is the first negative character in Egyptian stories, as he goes head-to-head with Horus in one of the great Egyptian myths. However, he also demonstrated many more positive attributes as a protector in nighttime warfare.

Set is best known for his role in the Egyptian epic known as the Osiris myth. In this story, Set is both the murderer of his brother Osiris and the defiler of his body. In this tragic story, Osiris’s sister and wife, Isis, along with her sister Nephthys, spend much time and emotional energy collecting Osiris’s body parts and attempting to put them back together.

In this, they have limited success, but they succeed in reanimating Osiris’s spirit long enough for Isis to have their son, Horus. The rest of the story is made up of several climactic battles between Horus and Set as Horus asserts his own right to power and seeks revenge against Set.

Sekhmet: Healer and Destroyer

The Sekhmet figure is depicted as a lioness. Sekhmet was a goddess of contrasts. She was fierce, aggressive, a goddess of destruction, and closely related to war.

She was, however, also associated with healing. Spells were often invoked to ward off disease or to cure it. In one story about the decline of Ra’s power over the Earth, the god sends the goddess Hathor in the form of Sekhmet to subdue the humans who have rebelled against him. The goddess’s bloodlust is unabated as the story progresses, even after the battle has ended. In her bloodthirsty ecstasy, she threatens to destroy Egypt and annihilate all life on Earth.

Realizing the threat this posed, Ra came up with a plan, assisted by the other gods. They built a large basin and filled it with beer, dyed red to resemble blood. Thinking it was blood, Sekhmet drank up the entire lake, becoming drunk. This put a stop to her destructive activities, and she returned to Ra’s side in a friendly manner.

Hathor’s Diverse Roles

Hathor was an Egyptian goddess of many aspects. She was often depicted as a cow or as a woman with cow horns. She was the goddess of music, dance, and fertility. She was also a protective goddess for miners and guided the dead through the underworld.

She was one of several Egyptian gods who served as the Eye of Ra. As such, she was his feminine counterpart. In this regard, she was a fierce protector and punisher of those who opposed him. On the other hand, she was a goddess of melody, celebration, love, sensuality, and maternal love. She was the wife of several male gods and the mother of children with them. She was one of the many faces that displayed the Egyptian concept of womanhood.

Geb’s Earthly Laughter

The god of the Earth, Geb, was characterised by an interesting feature. Ancient stories say his laughter caused earthquakes, which is why the Egyptians attributed this natural phenomenon to their god. They personified natural phenomena as the physical effects of the gods’ passions.

Geb is also often represented as an early divine king of Egypt, from whom his son Osiris and his grandson Horus inherited the country, after many conflicts with the chaotic, divisive god Set, the murderer of Osiris. Geb is the god of the arable land and the desert. It is in this desert where the dead rested for eternity or where, as the phrase “Geb’s gaping mouth” would have it, they were liberated. Others, who are not worthy of this fate, will remain trapped, rather than going to the fertile and verdant North-Eastern celestial Field of Reeds.

Nut: The Starry Sky

Nut is an important player in cosmology. She was the Egyptian goddess of the sky. She was usually depicted arching over the earth, her body covered in stars. She was believed to swallow the sun each night, who would then pass through her body to be reborn at sunrise.

Legends of the succession myths state that Ra, the god of the sun, ruled the world. He declared, “Let Nut not bear a child on any day of the annual cycle.” (There were only 360 days in the year at that time.) Nut pleaded with Thoth, the god of knowledge, who devised a plan and challenged Khonsu, the moon god (whose light was nearly as bright as Ra’s), to a game of dice. For each loss, he had to give up a part of his moonlight. He lost so often that Nut had gained enough light to create five extra days.

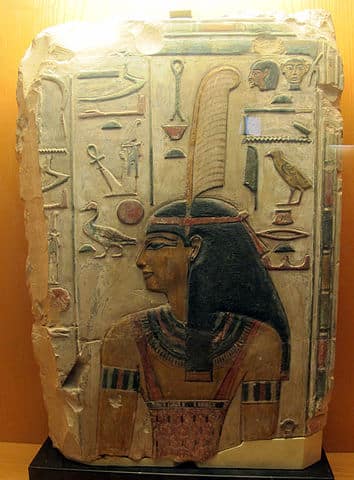

Ma’at: Cosmic Order Personified

Ma’at was not just another Egyptian goddess; she was the embodiment of the Egyptian ideals of harmony, order, truth, and balance. Her famous feather of Ma’at was used to weigh the heart in the afterlife. The ancient Egyptians believed that without Ma’at and the values she represented, the world would descend into chaos.

Sources of ancient Egyptian law are only sparsely represented in the existing literature. The ideals of justice were not elaborated into a list of legal provisions, but rather into the singular notion of Maat. Maat represented the basic principles of ethics and values, which formed the backdrop against which justice was dispensed, and that justice was always centered on the concept of truth and fairness. As far back as the Fifth Dynasty, around 2510-2370 BCE, the official who oversaw justice was referred to as the “Custodian of Maat”. In later periods, judges often embellished themselves with images of Maat.

Ptah’s Divine Craftsmanship

Ptah is a god who originated from the city of Memphis. His special creation story is that he did not physically create the earth, but thought and spoke it into existence. This creation story makes clear just how significant and influential thought and words were to the ancient Egyptians.

Ptah’s popularity and worship spread rapidly throughout all of ancient Egypt.

Ptah’s high priests became crucial during the Old Kingdom as the Pharaohs started more major projects. Assisting the vizier, Ptah’s priests became the main designers and leading craftsmen, responsible for adorning the royal tombs.

Ptah’s worship changed from the New Kingdom, especially in Memphis, his city of origin, and Thebes. In Thebes, the craftsmen working in the royal tombs began to associate him with the patron of craftsmen. As a result, a unique chapel called “The Sanctuary of Listening Ptah” was built in the vicinity of Deir el-Medina, the village in which the craftsmen lived. In Memphis, the outer enclosure surrounding the god’s chapel was decorated with giant carved ears, highlighting his role as the Egyptian god who listens to prayers.

Nephthys: Osiris’ Support

Nephthys isn’t one of the most famous gods. However, that does not mean she isn’t important. In Egyptian mythology, Nephthys was the goddess of the night and mourning. She and her sister Isis worked together to restore Osiris to life, and family matters are a common thread in most mythologies.

Nephthys was also a close companion to the brutal god Set. She was also a divine representation of the final stages of life, much like Isis is a representation of the final stages of life. In ancient Egyptian spirituality and religious cosmology, Nephthys was sometimes referred to as the “Guardian Goddess” or the “Supreme Deity.” These ancient Egyptian religious texts describe a god who is woven into divine intervention and constant protection.

Khonsu’s Lunar Cycle

Khonsu is a moon god in ancient Egyptian mythology with the head of a falcon. In timekeeping, he served to track the passage of time. His epithet, “The Voyager”, was a most appropriate description of the moon as it traveled across the night sky. Khonsu is also associated with many other titles, including Guardian, Trailblazer, Protector, and Healer. Khonsu, as a god, served as a protector of travelers who had to travel at night.

Called upon for protection from wild animals and in healing ceremonies, he was often viewed as a light in the darkness. Legends speak of when Khonsu introduced the light of the crescent moon. It was also a time of fertility for women and their cattle, and when new life-giving air was breathed into all creatures.

Imhotep’s Elevation to an Egyptian God

Imhotep was, of course, not a god in the first place. He was a historical person. He was credited with being the architect of the step pyramid. In recognition of his services, he was deified after his death. And as is clear, humans were given the status of gods.

Imhotep was one of the very few non-royal Egyptians who were deified after death. In fact, over the last few hundred years, only a few non-royal figures have been deified. The center of his cult was Memphis. Although intensive searches have been made, the burial place of Imhotep has not yet been found. Many archaeologists believe that it is hidden somewhere in Saqqara.

Two thousand years after Imhotep’s death, his image became a god of medicine and healing. As time went on, his cult merged with the deity Thoth, the Egyptian god of wisdom, especially in architecture, mathematics, and medicine, and was the patron god of scribes.

Neith: Crafting Destiny

Neith was one of the earliest Egyptian gods. Apart from warfare and hunting, she was also the “Weaver of the World” and this symbolized how the destinies of gods and humans were interwoven and perfectly made.

She was also sometimes celebrated as the first great creator and was thought to have shaped the universe and set its operations in motion. In some of the ancient Egyptian origin stories, Neith is described as being the mother of Ra and Apep. She was an ancient water goddess and was considered the mother of Sobek, the familiar crocodile. She was so frequently linked with the Nile waterway and its east bank, that sometimes she was said to be the wife of Khnum and sometimes with the source of the River Nile itself. In specific religious centers, she was linked to the Nile Perch, and formed the focus of a triad.

The goddess of craftsmanship and weaving, she wove the fabric of life again on her cosmic loom every day. In inscriptions within the temple at Esna, it is described how Neith gives birth to the Nun (first land) from the first waters. She then materialized each idea, thereby creating the thirty deities of the Egyptian pantheon. She’s also known as the “Unwed Mother Deity” because she didn’t need a partner.

Khepri’s Dawn Symbolism

Khepri was sometimes shown as a scarab and was explicitly associated with the rising sun. Khepri also symbolised rebirth and transformation. Khepri made the ancient Egyptians realise the circular concept of life, in which every morning the sun rises, and a new life is born.

Khepri wasn’t a major god and had no particular religious cult. Khepri always existed in the shadow of the mighty Ra. The cosmogonies of Heliopolis and later of Thebes assimilated this sun god. Khepri and Atum were often seen as two aspects of Ra: Khepri at dawn, Ra at midday, and Atum at dusk.

Khepri, the Egyptian god, was a creator, protector, solar god, and god of resurrection. The main attribute associated with Khepri was his power to renew and reinvigorate, as he did for the sun every morning. In tombs from the pre-dynastic periods of ancient Egypt, archaeologists have discovered mummified scarab beetles and amulets, leading to the belief that the veneration of Khepri, the Egyptian god, began in the very early history of ancient Egypt.

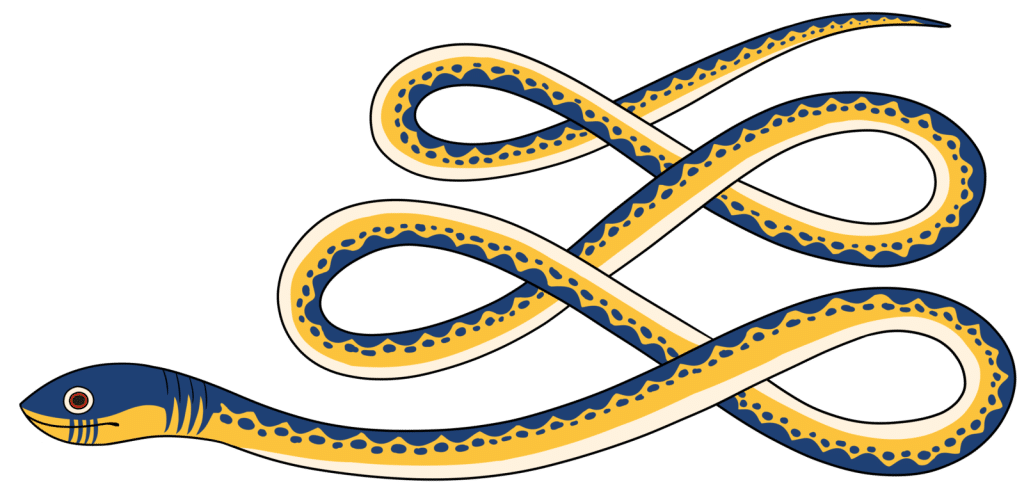

Apep’s Eternal Struggle with Ra

Apep, the serpent of the underworld, was constantly and consistently in conflict with Ra. While Ra made his nightly journey through the underworld, Apep would attempt to swallow Ra each night and bring about the permanent end of the day. Thus, Apep became symbolic of the ceaseless conflict between order and chaos.

Accounts of Apep’s battles with Ra became more detailed in the New Kingdom. In these tales, Apep was constrained to remain under the horizon. This circumstance, combined with his well-defined character, naturally associated him with the land of the dead. In one tradition, Apep waited at Bakhu, the mountain in the west where the sun made its nightly descent. In other accounts, Apep would hide, waiting for Ra in the Tenth region of the Night, to ambush him just before dawn.

Owing to the many places in which he could reside, Apep was also referred to as the World Surrounder. When he roused himself to do battle, his roar was said to be so loud that the underworld was set vibrating. According to some stories, Apep was bound to this realm because he had been the previous chief deity, overthrown by Ra, while others say his evil was so great that he was imprisoned.

Taweret: Protector of Mothers

While the hippopotamus goddess Taweret may seem a bit scary at first glance, she was most commonly invoked to protect people during childbirth. In fact, she embodied both the peril and the protection of childbirth, displaying the dual nature that so many Egyptian deities had.

In specific versions of one common myth, the Eye of Ra, angry with her father, travels to Nubia and becomes a lioness. When she eventually returns to Egypt, she does so as a hippopotamus, often identified as Taweret, who causes the Nile to flood. This myth highlights just how vital Taweret was as a fertility and regeneration goddess.

Some scholars have even proposed that this connection to the Nile’s flooding is why she was so often called the “Lady of Pristine Waters”. However, her equally important function in rejuvenating the dead should also be taken into account when considering this title. Not only did she give life to the living through childbirth and the Nile’s inundation, but she also cleansed the dead, purifying them so they could pass on to the next world.

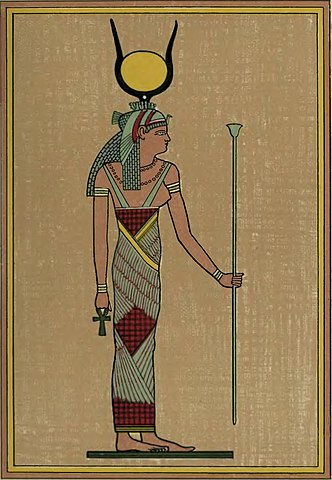

Isis: Magic and Motherhood

Isis is among the most venerated of the gods and is celebrated for her magical skills. She brings Osiris back to life and is also closely connected with maternity, care, and protection. In fact, she is strongly associated with love and devotion.

She, whose magic is second to none, can resurrect Osiris and also use her power to ensure the well-being and safety of Horus. In addition to being immensely strong, Isis is also known for her wisdom. She is repeatedly praised in the stories as being more intelligent than millions of gods. In the New Kingdom stories in particular, for instance in The Contendings of Horus and Set, she often uses her magic and cunning to outsmart Set, who is involved in a conflict with Horus, her son.

In one story, she takes the form of a girl and gets involved in a family quarrel similar to Set’s attempt to forcefully take over Osiris’s throne. When Set complains about this being unfair, Isis points out his own duplicity. In other stories, she uses her transformative magic to directly overcome Set and his followers.

The Isis-centered stories sometimes used to introduce magical texts are often presented as a mythological background for the purpose of enchantment. In one popular spell, for example, Isis creates a serpent that bites the much greater god, Ra, and weakens him. She then offers to heal him in return for his elusive and powerful actual name.

After repeated cajoling, Ra finally reveals his name, which Isis then passes on to Horus, to increase his majesty as king. This story could be a case of an after-the-fact explanation for the fact that Isis’s magical skill surpassed all other gods’. It is interesting to note that although in the story Isis uses her magic to overwhelm Ra, she was likely born with an already uniquely exceptional set of powers, even before she discovered the secret name of Ra.

Sobek’s Crocodilian Might

Sobek was also a deity who could take the good and bad of the Nile as a whole, becoming both dreaded and revered, much like his living counterparts. Nile crocodiles were both a hazard and a benefit to the Egyptian way of life.

Sobek is most recognized as a powerful and brutish deity. He shared the characteristic of his eponymous creature, the Nile crocodile, itself a symbol of power and violent aggression. He is, as such, referred to as “he who revels in theft,” “he who consumes as he couples,” and “sharp-toothed.”

This characterization is expanded with the stories of Sobek, but underneath the brutal exterior of the crocodile god is a very compassionate heart. In many myths Sobek takes on the mantle of protector, once Sobek began to be associated with Horus and was integrated with Osiris, Isis, and Horus in the Middle Kingdom, he would often be called upon to heal, specifically in the restoration of the murdered Osiris at the hand of Set.

As such, Sobek became characterized as a protector deity, using his own innate aggression against those who would harm the innocent. As such, he was both more highly worshipped and received more offerings, especially later in ancient Egyptian history. During the Ptolemaic and Roman periods in Egypt, it was common to mummify crocodiles and present them as offerings at temples dedicated to Sobek.

In summary, the stories of the Egyptian Gods are a fascinating insight into the ancient Egyptian civilization. The gods had unique characteristics and compelling stories that have been told and retold over the centuries. They remain an important part of our history and have contributed significantly to the development of human culture. As we conclude this short introduction to the Egyptian Gods, we invite you to learn more about these fascinating deities and their stories.