Exploring the Order of Assassins: Origins, Evolution, and Downfall

The Order of Assassins is also known as the Hashshashin- both titles evoked fear and mystery in their enemies. It began in the late 11th century amid the Crusades, as a secret society wielding influence over much of the Islamic world. Throughout their existence, the Assassins used religion, politics, and murder to further their goals and safeguard their allies from enemies. They were the Ismaili sect of Shia Islam, based in Persia and Syria.

Their legacy of the Order of Assassins, mysterious killers, creates difficulties when recounting the factual events of their existence. Operating out of mountain strongholds such as Alamut in Persia, the Assassins were a political and military force to be reckoned with by both the Crusader states and the Islamic empires of the time. The Order finally met its demise in the mid-13th century when it fell to the forces of the Mongol Empire.

The Rise of the Order of Assassins

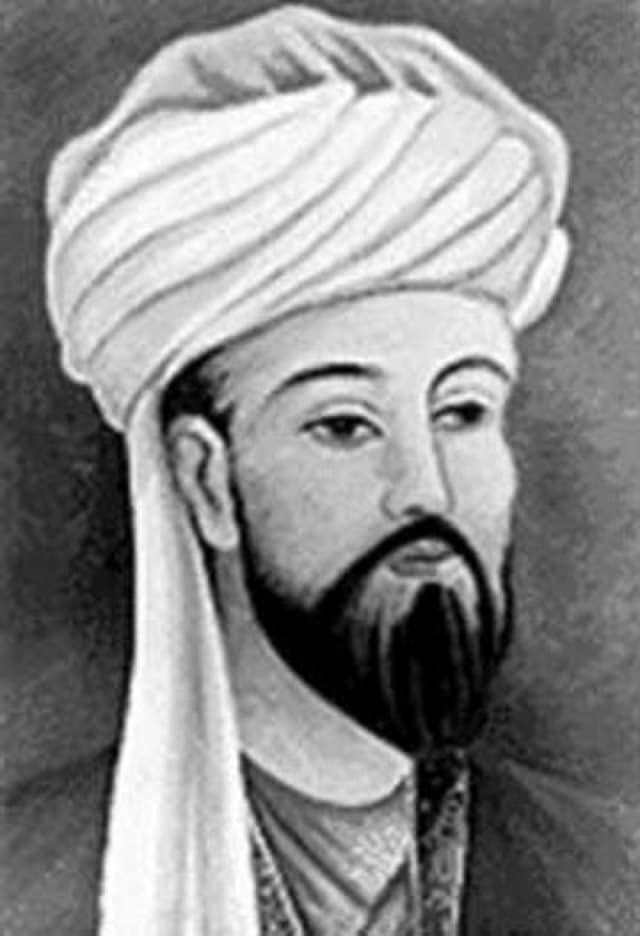

Hassan-i Sabbah went from being a student to a supreme leader. Sabbah studied in Cairo as an intellectual student under the Fatimids and used their knowledge to gain power in Persia. He was born in Qom in about 1050 to a family of noble Arab descent. In 1090, Hassan-i Sabbah captured Alamut Castle through strategy and trickery. He then converted the castle into a self-sustaining force of defense as well as a re-education center for his Order of Assassins. During his time there, he created useful religious manuscripts and spread his reign of fear through both political strategy and assassination.

Commanded by Sabbah’s eventual successor, Kiya Buzurg Ummid, the Assassins’ purchase of Lambsar Castle further strengthened their presence in northern Persia. The Assassins posed no threat to the Crusaders for fear that they would retaliate against Muslims. Instead, they focused their attentions on Muslim targets, building Assassins’ fortresses throughout Persia, and began killing Seljuk officials and rivals. This helped consolidate their power during the reign of Sabbah, who became known for turning assassination into an effective political and religious weapon.

Fortresses were seized across Persia and Syria as the Order of Assassins continued their expansion. The capture of many vital strongholds allowed the Order to grow and take advantage of opportunities against the Seljuks, further expanding its power. Despite various setbacks, including failed sieges and temporary civil war within the Seljuk empire, the Assassins began exploiting the situation and used political maneuvering to ensure their survival. Through Sabbah’s influence and ability to manipulate both the common people and the political leaders of the time through assassinations, intrigue, and subterfuge, he managed to carve out his own religious faction in Near Eastern politics.

The Mystique of the Order of Assassins: Life, Training, and Beliefs

Life as an Assassin consisted of many things, including constant training and strict rules that needed to be followed. Initiates of the Order, known as fida’is, were physically and mentally fit from training at a young age. Skills they learned included sneaking, reconnaissance, planning, and fighting. Skills that allowed them to complete tasks flawlessly and selflessly for the greater good of the Order. Members lived an ascetic lifestyle confined to the castle, such as Alamut. They would fully devote themselves to following Hassan-i Sabbah and the Order’s cause. Training involved combat skills and teaching them how to be good spies. They would also learn about theology, philosophy, and languages.

Life as an Assassin also consisted of following the Assassins Creed. The Order created beliefs that blended Ismaili Shia Islam with mysticism. The Assassins would hold special ceremonies to initiate recruits. These ceremonies would help show loyalty and sacrifice to the cause and members. It taught them about how to live life by following the truth. There was a hierarchy system that all members fell under. Starting from the bottom were the fida’is, then there are greater levels of initiates who know more about the doctrines within the Order of Assassins than the former. On top of the hierarchy is the Grand Master.

Medieval people thought of Assassins as frightening and courageous. They were known to get anywhere and anyone, no matter how well guarded they are. Not only did they scare people, but they also gained respect from some because of the high-profile people they killed. Assassins are known to be among the first secret societies and remain among the most mysterious organizations.

The Syrian Domain of the Assassins

Eventually, the Order of Assassins sought to expand westward into Syria. Hassan-i Sabbah ordered his first da’i, al-Hakim al-Munajjim, to conquer the province of Syria and begin missionary activities there. He infiltrated Aleppo and formed an Assassin cell there. In Aleppo, the new Assassin cell allied itself with the emir Ridwan of Aleppo, and together they were responsible for the murder of Janah ad-Dawla.

Their growing power within Aleppo caught the attention of neighboring rulers, who raised a large army to drive them out of Syria. This didn’t stop the Assassins, however, as they withstood attacks from their Syrian enemies and bought time by negotiating with them, using subterfuge, and killing their way into power. The Assassins captured significant fortresses in northern Persia, including Khalinjan. With fear and militaristic victories, the Hashshashins gained control throughout Persia and Syria.

The Order continued their operations and targeted killings in Syria and produced assassins who committed some high-profile assassinations. It has been recorded that Mawdud, atabeg of Mosul, was murdered by two Assassins sent by his brother Nasir al-Dawla, and it has been recorded by some Muslim chroniclers that even Mahmud’s father, the great Buri, who founded the Burid dynasty, was killed by an Assassin.

Following Ridwan’s death and Alp Arslan al-Akhras’s rise to emir of Aleppo, Assassin activity would temporarily cease until after Alp Arslan’s assassination. Through forging ties within society from intermarriages, alliances, and just outright terrorism, the Order of Assassins established a foothold for itself in Syria.

The Era of Succession and Expansion

Following Hassan-i Sabbah’s death in 1124, the Order of Assassins entered a new chapter under the leadership of Kiya Buzurg Ummid. This transition period did not denote weakness but rather a continuation of Sabbah’s legacy, as evidenced by the strategic expansion and fortified resilience against external threats. The Seljuks, presuming a moment of vulnerability, launched attacks against the Assassins’ strongholds, only to face stiff resistance and tactical reprisals. The Assassins’ adeptness at infiltration and assassination was once again demonstrated with the cunning elimination of the Seljuk vizier Mu’in ad-Din Kashi, underscoring their enduring potency and the futility of confrontation.

Simultaneously, they broadened their influence in Syria, adapting their tactics to the unique political landscape. The strategic murders of key figures, such as the atabeg of Mosul and the Burid dynasty’s founder, showcased their intent to assert dominance and disrupt the prevailing power structures. The Assassins’ covert operations and alliances, notably with Toghtekin and his successors, facilitated their expansion while complicating the Crusaders’ and Seljuks’ efforts to counteract their presence.

Bahram al-Da’i’s rule was succeeded by his lieutenant, Isma’il al-‘Ajami. During their time in power in Syria, the Assassins experienced both success and failure. Although they were eventually expelled from Syria and lost their leaders through assassination or captivity, they had managed to eliminate important political figures through fear and respect.

Muhammad Buzurg Ummid succeeded Buzurg Ummid following his death in 1138. The Assassins did not weaken following this succession. They continued expansionist policies, captured fortresses, and carried out assassinations against caliphs and viziers. Their involvement in the Crusades helped shape Middle Eastern geopolitics.

This period of succession and growth helped solidify the Order of Assassins as power brokers of the Middle Ages and set the foundation for their legendary lore to come. With their knowledge of strategy and strong devotion to their beliefs, they maintained power for years after Hassan’s death by stealthily maneuvering through the medieval political games of diplomacy and assassination.

Transition and Legacy: Hassan II to Rashid ad-Din Sinan

The rule of the Assassins then went into a period of flux following the death of Hassan-i Sabbah in 1124. Sabbah’s successors were Hassan II and then Rashid ad-Din Sinan. The rule of Hassan II was to drastically change Sabbah’s outward military posturing, making it more esoteric in nature. Hassan II declared the doctrine of qiyāma in Ramadan 559 AH. Qiyāma (“resurrection”) was a doctrine that effectively changed the strict Sunni Islam of Hassan-i Sabbah into a more spiritual religion concerned with inner meanings rather than outward representation of Islam through Sharia law. Hassan II’s edict led to revolts within his own ranks.

Sinan was born Rashid ad-Din and nicknamed the “Old Man of the Mountain”. He was their strongest leader yet, making their hold on Syria into a campaign of political intrigue and terror. Sinan’s campaigns in Syria were notable successes against both Crusader and Muslim adversaries. These victories reminded others that the Assassins were still a force to be reckoned with in the era’s convoluted political affairs.

Sinan is known to have quarrelled with Saladin at various points; however, his attempts on Saladin’s life were thwarted until Saladin eventually agreed to make peace with Sinan. Relations between the Assassins and Saladin and the Muslim World overall have had ups and downs throughout history, though Sinan was one of the masters of pragmatism.

The Assassins Order still faced threats from the Mamluks, leading Sinan to try to broker an alliance with one of Saladin’s sons to save their state in Aleppo. Sinan later led his followers into a full-frontal assault against the Templars after they had launched a massive attack against the Assassins’ Syrian strongholds.

During Sinan’s rule, the Order remained dominant through sheer political influence and assassination. Sinan died in 1193. With Sinan’s death, the Assassins remained influential under the leadership of Alamut, though they would lose much power in the coming years as the threat of a Mongol invasion drew near. Hassan II’s succession by Sinan marks an important period in the Order of Assassins’ development.

A New Era under Hassan III

Muhammad III’s successor, Hassan III, immediately ushered in an era of pragmatism. Hassan III began openly practicing Sunni orthodoxy (Taqiyyah) out of necessity to ensure the Isma’ilis’ survival and to acknowledge Abbasid caliph al-Nasir as their legitimate Caliph. The Order of Assassins’ strength dwindled after Hassan III’s reign, as their assassination attempts decreased.

During Hassan III’s rule, the Order still committed acts of assassination and sabotage. In 1213, Raymond, the teenage count of Tripoli, was murdered by Assassins. After this assassination, Bohemond IV of Antioch and the Knights Templar began the siege of Qala’at al-Khawabi, home to the Assassins. The stronghold was saved by Ayyubid Sultan Al-Kamil, who ordered his army to march to Damascus to defend against the Crusaders. The Assassins’ failed attempt to assassinate Bohemond IV demonstrated the limits of the Order’s reach.

Majd ad-Din became chief da’i during the reign of Hassan III. He stopped paying tribute to the Seljuk sultanate of Rûm and instead took the tribute money for himself. Hassan III died suddenly in 1221, most likely poisoned by Majd ad-Din. His young son Muhammad III became Imam after his father’s death. Muhammad III spent much of his reign wavering between practicing Shia orthodoxy and Taqiyyah (the practice of concealing religion in Islam) due to the rapidly approaching Mongols.

The Mongol threat forced the Assassins to begin taking an interest in European politics. Majd ad-Din met with Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor. He later agreed to sign a peace treaty with the Knights Hospitaller after his capture at Khfir. The Order of Assassins’ presence eventually decreased during the time of Muhammad III. He was murdered in 1255, and Rukn al-Din Khurshah became Imam after his death.

1210–1255: Muhammad III’s assassination in 1221 sparked a change in leadership and energy within the Isma’ilis. During this time frame, the Order of Assassins tried to stay involved in local politics, but could not stop change from occurring.

Legacy of Shadows: The Order of Assassins’ Notable Kills

The Order of Assassins was a secretive order known mostly for its political killings. Here is a list of some of the most notable assassinations they committed. Included are figures who were assassinated, how they were assassinated, and the consequences of their deaths.

Nizam al-Mulk, 1092, Near Baghdad – The Seljuk vizier was murdered by a disguised Assassin. This major assassination changed the political balance of power in the Seljuk Empire. His murder sent ripples throughout the medieval Islamic world.

Raymond II of Tripoli, 1152, Tripoli – Murdered by a handful of Assassins in the streets, his death brought conflict between the Crusader states and the Order of Assassins, who responded by fortifying their strongholds and taking the fight to the Order of Assassins.

Conrad of Montferrat, 1192, Tyre – He was assassinated by two Assassins disguised as monks. His death sparked a power struggle, realignment of loyalties amongst the Crusader states, and rumors of participation by fellow Crusader nobility.

Janah ad-Dawla, 1103, Homs – He was assassinated while he was in a mosque by Assassins posing as worshippers. His assassination led to the Assassins penetrating Syria. This laid the foundation of the Assassin base in Syria.

Al-Afdal Shahanshah, 1121, Cairo – The Fatimid vizier’s death at the hands of the Order of Assassins destabilized the Fatimid Caliphate, leading to internal strife and weakening its position against the Seljuks and Crusaders.

Edessa’s Deputy Governor, 1126, Edessa – Assassinated during a public event; this killing underscored the Assassins’ willingness to strike in Crusader territories, increasing the Crusader states’ military expenditures on espionage and personal security.

Mawdud of Mosul, 1113, Damascus – His assassination disrupted the Seljuk military campaigns against the Crusaders, temporarily easing pressure on Crusader states and reorganizing Seljuk military strategy.

Patriarch of Antioch, 1203, Antioch – Murdered during a liturgical service, this act terrorized the Christian ecclesiastical hierarchy and led to increased security measures within the principalities.

Shah Jalal ad-Din, 1107, Persia – Killed in his private quarters, demonstrating the Assassins’ capability to breach even the most secure of locations, leading to increased paranoia among political leaders.

Caliph al-Amir, 1130, Cairo – His assassination significantly weakened the Fatimid Caliphate, accelerating its decline and affecting the balance of power in the Middle East.

Mu’in ad-Din Unur, 1149, Damascus – The regent of Damascus’s murder led to a power vacuum in the city and influenced subsequent regional power struggles.

Ibn Al-Khashab, 1125, Aleppo – His death, executed in broad daylight, sowed fear among the Order of Assassins’ opponents and led to retaliatory actions against suspected Assassin sympathizers.

Peter the Venerable, 1155, Near Cluny – Though not directly assassinated, his death, under mysterious circumstances after denouncing the Assassins, contributed to the mythos surrounding their reach and power.

Ahmad Sanjar, 1157, Merv – Survived an assassination attempt, but the incident led to a significant shift in the Seljuk’s policies towards the Assassins, including attempts at alliances and negotiations.

Frederick Barbarossa, 1190, Asia Minor – Despite the Holy Roman Emperor’s natural death, it was rumored that he was targeted by the Assassins, illustrating the widespread fear and respect for the Order, affecting the morale of Crusader forces.

Philip of Mahdia, 1153, Mahdia – The ruler’s assassination in his bathhouse exemplified the Assassins’ ingenuity and boldness, leading to a brief period of chaos and power struggles within Mahdia.

Saladin, 1176, Near Aleppo – The unsuccessful assassination attempt against Saladin led to a cautious peace between him and the Assassins, illustrating the complex relationships between the Assassins and the region’s rulers.

Richard the Lionheart, 1191, Near Jaffa – The failed attempt on his life led to increased security measures around the king and heightened tensions between the Crusader states and the Assassins.

Al-Mustarshid Billah, 1135, Near Hamadan – The Abbasid Caliph’s murder by Assassins underlined the dangerous position of even the highest Islamic authority figures, leading to a reevaluation of the caliphate’s strategies towards the Assassins.

Count Raymond III of Tripoli, 1187, Tripoli – His assassination destabilized the region further, contributing to the loss of critical territories to Muslim forces during the subsequent period.

Each of these assassinations not only claimed the life of a key figure but also precipitated a ripple effect, altering alliances, inciting wars, and shifting the balance of power across the medieval world. The Order of Assassins, through these targeted killings, demonstrated their influence on the historical narrative, a legacy of shadows that continues to fascinate and horrify to this day.

The Final Chapter: Collapse of the Assassin Order

The demise of the Assassins finally began to take shape in the mid-13th century. Starting with the Mongol invasions of Persia and Syria in 1253, the Assassins’ strongholds were destroyed one after another until Maymun-Diz was besieged by Hulagu Khan’s forces. The surrender of Alamut by Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah to the Mongols in 1256 marked the collapse of the Nizari Ismaili state. Lambsar fell in 1257 and Masyaf in 1267, marking the end of the Assassins as a regional power.

Although weakened by the Mongol invasion, some surviving Assassins were able to retake Alamut in 1275. This occupation lasted for a short time before being put down once more. Rukn al-Din Khurshah was killed, extinguishing hope of restoring the Order to its former self. Small groups of Assassins managed to hold out as well, most notably at Gerdkuh, which fell soon after. Although their actions were heroic, nothing could stand against the Mongols; the Assassins’ political influence and might were gone forever.

The fortunes of the Assassins now followed two separate paths. The Assassin state collapsed in Persia but somehow survived in Syria by cooperating with the Mamluks against their common enemy, the Mongols. Sultan Baibars eventually saw them as a useful addition to his army and stripped them of independence, subjugating them to his will. Once rulers of a great independent power, they had now become auxiliaries to the Mamluks.

During the transition, the Order of Assassins worked to keep pace with the changing politics of the time. They established alliances and later submitted to the Mamluks. However, by the late 1270s, Baibars had destroyed all remaining Assassin fortresses, and the Assassins ceased to exist as an independent power. Baibars had Philip of Montfort assassinated in 1270, and with this, one could consider the Assassins’ medieval career over.

The Order’s story from 1210 to 1273 reflects the uncertainty of the Middle Ages. They went from being a force to reckon with to being exterminated and used as puppets of the Mamluk army.

A Legacy Carved in Shadows

The history of the Order of Assassins extends beyond the medieval period and remains relevant in modern society. From the rise of Hassan-i Sabbah to their eventual fall at the hands of the Mongols, the Assassins have a rich history full of captivating stories. Today, their legacy lives on in popular culture, from novels, movies, and video games that draw inspiration from their fascinating history.

The legacy of the Assassins’ Order has had a significant impact on the Middle East during medieval times and continues to be remembered today. Despite their defeat, the fortresses they built still stand strong as a reminder of their former power. The story of the Order of Assassins will always be remembered as one of the most interesting tales of conflicts between faiths, politics, and war.