Inside Andersonville: Unveiling the Horrors of the Civil War’s Infamous Prison

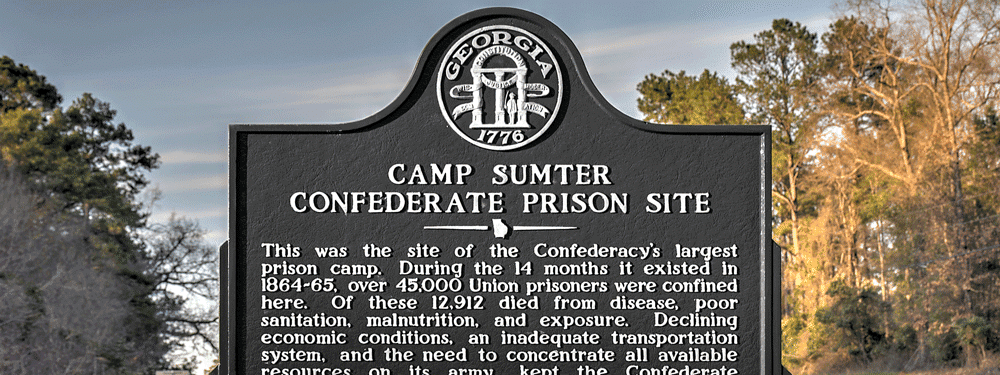

The Andersonville Prison, officially known as Camp Sumter, is a notorious prisoner-of-war (POW) camp from American history. Built by the Confederacy during the American Civil War, it was intended as a temporary facility for Union soldiers. However, it quickly became a death camp for thousands of prisoners.

Located in rural Georgia, the prison was the site of unimaginable suffering, disease, and starvation. It was overcrowded and under-supplied, with thousands of Union soldiers crammed into unsanitary and inhumane conditions. The result was a staggering death toll of nearly 13,000 in just over a year.

Andersonville is a tragic reminder of the horrors of war, with a legacy that still resonates today. The prison’s reputation as a place of inhumane treatment and neglect is still being reckoned with and has had a lasting impact on discussions of prisoner treatment and military ethics.

The story of Andersonville is one of both the voices of the prisoners who suffered there and of those who perished in its infamous confines. This article will explore the history, conditions, and legacy of Andersonville and the stories of those who were there.

The Establishment of Andersonville Prison

As more and more Union soldiers were captured in 1864, the Confederate government found it increasingly difficult to handle them all at the overcrowded and ill-equipped camps that already existed. There was a growing desire among Confederates in charge of handling prisoners to open a new camp that could take prisoners away from other camps that were strained for space and resources, but keep them securely out of the hands of the Union.

After exploring several possibilities, a location in Sumter County, Georgia, was chosen for its remote location, proximity to a railroad line, and what was believed to be a plentiful water source. It became known as Andersonville Prison or, because it was not officially designated as a prisoner-of-war camp until December 1864, Camp Sumter.

Andersonville Prison was chosen in part because of the perceived difficulty for Union forces in reaching it. In the deep South, and quite a distance away from most of the main fighting, it was thought that it would not be in danger of a Union raid to free the prisoners. Moreover, the thick forests and hilly terrain around Andersonville were expected to make it very hard for prisoners to escape. Finally, the prison’s proximity to the Southwestern Railroad allowed prisoners to be quickly and easily transported from other camps across the South to Andersonville, where thousands were moved in its first year of operation.

In late 1863, construction of Andersonville Prison began under the direction of Confederate Captain W. Sidney Winder, who was sent to the area in September 1863 to prepare for the arrival of prisoners. The original design of the camp called for a prison stockade covering about 16.5 acres, surrounded by a 15-foot-high wooden fence made of round, rough-hewn pine logs. Guard towers were erected at regular intervals around the perimeter so Confederate sentries could watch over the Union prisoners.

A small creek, Stockade Branch, ran through the compound, which served as both a drinking water source and a drainage ditch for prisoners and rainwater. The original plan did not call for any wells or other water sources, which later became a major problem as the prison population increased. Winder’s plans called for a maximum of 10,000 prisoners to be held at Andersonville.

Union prisoners began to arrive at Andersonville in February 1864, but within a few months, the number of captives there quickly outstripped the original design and plans. The size of the stockade was doubled with an additional 10 acres added in June 1864, but even this did not slow the rise of the number of Union prisoners there. The additions were poorly constructed, as the Confederate government was short on supplies, staff, and materials. The problem of prisoner overcrowding at Andersonville and other Confederate camps continued to be a significant problem for the government in Richmond.

Harsh Conditions Inside Andersonville

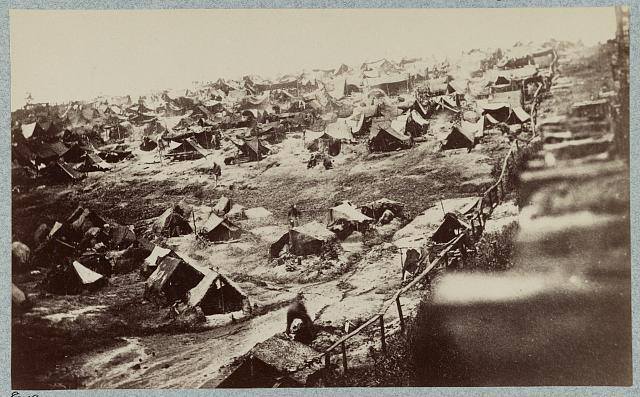

The conditions Union prisoners were forced to face at Andersonville started at the very beginning. The prisoner-of-war camps held by the Union had barracks where Union captives at least had a roof over their heads when not working outside. However, the stockade at Andersonville was nothing more than an outdoor prison. It had no barracks so every man was on his own.

With virtually no supplies, many men dug holes in the ground, and others, with a bit of ingenuity, used scraps of fabric, branches, and other materials, along with bits of clothing, to cobble together makeshift shelters. Those less fortunate still huddled under the hot sun in the summer, in downpours during the rain, or shivered during cold nights without any cover at all. Combined with a lack of clothing and blankets, exposure was an ever-present threat.

Andersonville suffered from an extreme overcrowding problem that made everything in the prison worse. Although the stockade itself could have housed 10,000 men in tolerable conditions, by the end of the war, over 45,000 men were imprisoned there. Space was at a premium, and the prisoners were so crowded together that it was difficult to move around, much less find enough space on the ground to sleep at night.

The enormous numbers of prisoners who arrived at Andersonville, due to poor planning by prison authorities, caused order to break down. There was little room for men to cook the little food they received, to clean themselves, or to dig latrines. In turn, the lack of sanitation facilities and the close quarters quickly resulted in widespread disease outbreaks that killed as many as starvation.

Water was the most significant factor in the breakdown of Andersonville. The Confederate government never got a water delivery system set up at the prison, and prisoners were expected to make do with a creek running through the prison compound, known as Stockade Branch. Prisoners used this small creek for bathing, waste disposal, and drinking. Needless to say, it was filthy, and the result of thousands of men using it for bathing and waste was a stagnant breeding ground for dysentery and other diseases.

Drinking from the water hole, according to one former prisoner named John McElroy, “produced a burning sensation that was worse than the thirst.” As McElroy and others drank from the hole, he was forced to deal with the unsanitary conditions:

“The water we drank was thick with filth and the stench that arose from it was indescribable. We had no other water, and so we were forced to drink it and hope that it did not make us sick.”

The unavailability of any other water source meant that prisoners had no choice but to continue drinking the filthy water and, as a result, dysentery became rampant.

Food shortages were a well-documented problem at Andersonville, as the Confederate government was having a hard time providing enough food for its own army, let alone the prisoners. Food rations at Andersonville mainly consisted of coarse cornmeal, with a small portion of beans occasionally and, if available, spoiled meat.

Many of the prisoners, who had never eaten such a diet, suffered from severe digestive problems, which further malnourished them. As the food supply continued to dwindle, some prisoners began eating rats, insects, and whatever else they could find to avoid starvation. The lack of essential nutrients led to a condition called scurvy. Men who suffered from scurvy had painful, swollen gums, loose teeth, and sores all over their bodies that would not heal.

The prisoners at Andersonville also faced a high risk of disease. Dysentery, scurvy, and gangrene were common ailments at the prison, and because of the lack of access to medicine and good hygiene, even minor wounds became life-threatening. The few Confederate surgeons at Andersonville had little more than a knife to tend to the sick and wounded. Because the prison had so few medical supplies at its disposal, the Confederate government was unable to send them any assistance.

Prisoners who fell ill at Andersonville were usually left to suffer, as there was no way to isolate the sick from the other prisoners. The only hospital at the prison was a small tent set up outside the stockade, with little staff and no supplies to treat thousands of men. As conditions at Andersonville continued to deteriorate, it became less a prison and more a graveyard.

The Infamous Stockade and the Dead Line

Andersonville stockade was a 15-foot-high wall of rough-hewn pine logs that encircled the prison. The stockade towered over the prisoners and kept Union captives contained while discouraging escape attempts. There were watchtowers built all around the stockade walls from which Confederate guards were able to watch the movements of the prisoners day and night. Armed with rifles, the guards were ordered to shoot any prisoners they saw trying to escape from Andersonville.

The stockade walls and the vast number of captives inside made Andersonville a deathtrap. Escaping from Andersonville was almost impossible for a number of reasons.

The most ominous of all features was known as the Dead Line. It was an imaginary line that ran just inside the stockade walls and was marked off by wooden posts. If a prisoner intentionally or accidentally crossed the Dead Line, he was shot to death on sight. Prison guards in the watchtowers were constantly on the lookout for transgressors, and some guardsmen enjoyed shooting prisoners who accidentally or intentionally crossed the Dead Line. Dorence Atwater, a survivor of Andersonville prison, recalled: “Men would step too close in their desperation for clean water and be cut down without hesitation. The dead lined the fence like warnings to those who remained.”

Andersonville’s Dead Line was a grim reminder to prisoners that escape was almost unthinkable. With no real fence between them and the Dead Line, some prisoners crossed it in an attempt to get clean water or a brief respite from the miserable conditions within the stockade. Other prisoners, weakened by starvation and disease, accidentally stepped too close to the line and were shot down without warning. Rigorously enforced, the Dead Line became one of the most feared aspects of the Andersonville prison.

Andersonville prison did not hold its captives indefinitely, and some desperate men attempted to escape. A few prisoners dug tunnels below the stockade walls with makeshift tools or even their bare hands, and some escapees were able to pass as Confederate soldiers or slip away unnoticed when prisoners were being transferred from other camps. But most escape attempts were thwarted, and it was nearly impossible for escapees to reach Union lines.

Confederate patrols were always on the lookout for deserters, and the thick Georgia swamps and bogs made for difficult travel. Prisoners who attempted to escape were often too physically weak to make much of a difference. If caught, they were usually executed; if not, they returned to Andersonville to face harsher treatment than ever.

Despite the dangers of the Dead Line, some prisoners chose the possibility of death over life in the stockade. There were many stories of prisoners who stepped over the line and faced their fate by a bullet rather than the slow death of starvation and disease that the stockade promised. To many of the prisoners, the stockade walls and the Dead Line were more than a prison. They were a constant reminder of the hell that was Andersonville, where death was all around, and freedom seemed but a dream.

Famous Soldiers Housed at Andersonville and Confederate Guards’ Accounts

Andersonville also contained a large number of notable prisoners. One such prisoner was Sergeant Major Robert H. Kellogg of the 16th Connecticut Infantry. He arrived at the camp in May 1864. Kellogg later wrote about his experiences at Andersonville. He wrote that prisoners “suffered from every species of woe, from the want of food, the want of clothing, the want of shelter, and medical attention.”

Dorence Atwater was a Union soldier and member of the 14th Connecticut Infantry who escaped Andersonville. Atwater kept a list of the dead in Andersonville despite Confederate authorities trying to keep the number of dead from being documented. Atwater’s list of the dead would be used as evidence against Confederate officers at their trial after the war.

The most famous prisoner to survive Andersonville was Father Peter Whelan. Father Whelan was a Catholic priest living in Savannah, Georgia, who chose to enter Andersonville to comfort Union prisoners. He was not a prisoner himself but stayed in the prison to offer religious support to as many prisoners as he could.

Father Whelan helped distribute food to the sick and dying and provided last rites for those who were dying. He was later called the “Angel of Andersonville” by those he helped. He provided solace and a measure of comfort to the prisoners while he could, despite interference by Confederate authorities. Father Whelan’s actions had a lasting impact on the survivors of Andersonville. They remembered his kindness amid the brutality.

Life for the Confederate guards at Andersonville was also hard, but not as bad as it was for the prisoners. Many of the guards were poor and had only recently joined the army. Some were men too old for military service who were assigned to Andersonville as part of their duties. Guards at Andersonville were sent there from various Confederate armies. The positions at Andersonville were seen as a place to put young, inexperienced soldiers or wounded veterans from both armies who were recovering from battle wounds.

These men were the lowest rank in the Confederate Army. This status gave the guards at Andersonville the ability to abuse prisoners without punishment. Some guards at Andersonville sympathized with prisoners. Guards reported this in letters to their families. These men were following orders in a situation they could not fix. The Confederate government was falling apart by this time in the war, which was the main reason for the poor conditions at Andersonville.

Confederate soldiers used various excuses to explain the conditions in Andersonville to themselves. Confederate soldiers blamed the Union for the deplorable conditions at Andersonville. Union officials suspended prisoner exchanges in 1864, so Confederates believed the conditions at Andersonville were partly the Union’s fault. Other guards abused prisoners for their own amusement. Guards would find creative ways to torment the prisoners to give themselves power.

Former Confederate guards wrote about their time at Andersonville, and many believed that prisoners were trying to undermine the Confederacy. This belief allowed them to ignore the prisoners’ suffering and their own shortcomings as guards. Guards at Andersonville acted as they saw fit because they had so much power and no oversight. Confederate commanders believed that Andersonville was suffering from the general supply shortages caused by the war rather than outright cruelty. This thinking was partially true as the Confederacy’s infrastructure was collapsing at the time of Andersonville’s operation, but guards also exploited the situation to commit abuse.

Captain Henry Wirz was the commander of Andersonville. Wirz was the face of the Confederate government at Andersonville for the prisoners. Wirz treated prisoners in various ways, depending on who was imprisoned. Wirz had a different attitude towards different prisoners. Wirz had trouble with scarce resources at Andersonville and did what he could to help the prisoners despite the supply shortages. Other accounts of Wirz, however, portray him as uncaring. Wirz’s trial and execution after the war left him in infamy as one of the few men held personally responsible for the conditions at Andersonville.

The Raiders and Regulators

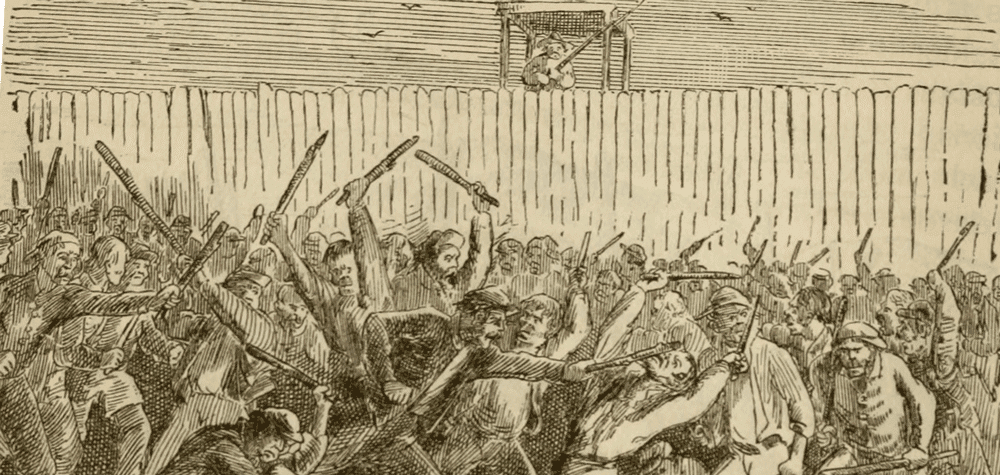

Disease, starvation, and Confederate apathy killed and sickened thousands of men at Andersonville, but another hazard also threatened the inmates: other inmates. A gang of lawless and violent men called themselves the “Raiders,” and they preyed on their fellow captives. Raiders would steal food, clothing, and even valuables from sick or weak prisoners, often beating or even murdering their victims. With rations and clothing already scarce, the Raiders made life even more miserable for the men who were trying to survive. The Raiders felt free to act with impunity because the Confederate guards did nothing to stop them.

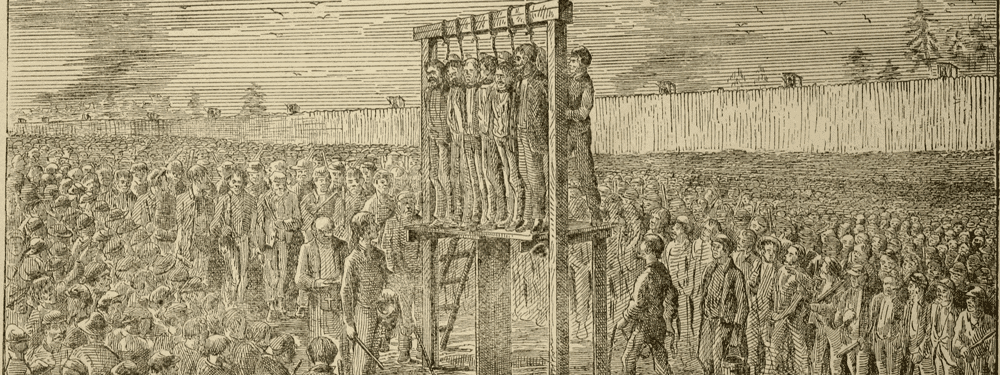

A group of prisoners banded together to put an end to this lawlessness. Calling themselves the “Regulators,” the men organized a vigilante justice system to mete out justice against the Raiders. With the begrudging consent of commandant Henry Wirz, the Regulators set up a court inside the prison. Prisoners served as judge, jury, and executioner. The accused Renegades were called to appear before the tribunal, and the captives put their questions to the alleged lawbreakers. Some of the Raiders were beaten and released, while others were banished to the outer limits of the stockade, but some of the worst Renegades were sentenced to death by hanging.

The most decisive action of the Regulators came in July 1864. After a series of trials, the Regulators convicted several Renegades and hanged six of them in front of a crowd of thousands of prisoners. The execution was both a warning to other Raiders and a moment of catharsis for the thousands of prisoners who these thugs had victimized. Crime continued in Andersonville, but the Regulators had significantly reduced the Renegades’ power and restored a measure of order among the prisoners.

The Liberation & Public Reaction to Andersonville

As the Confederacy collapsed in April 1865, Andersonville was left in a state of abandonment. The Confederates evacuated the last prisoners, either releasing them or transferring them to other locations. Union forces that entered the area soon after found themselves in what many described as a “hell on earth.” Gaunt men with scant clothing stumbled out of the malodorous stockade, too enfeebled to stand or walk. In some cases, death had released them from their agonies. The sight of these men and the conditions that they had endured was enough to shock soldiers and officers who had grown callous from years of warfare.

Reports of conditions in Andersonville quickly spread through the North, inciting public outrage. Survivors’ accounts and the skeletal remains of thousands of Union soldiers were seared into the minds of Northern readers. Political leaders and the press clamored for retribution, particularly against Henry Wirz, the prison’s commandant. Andersonville became an icon of Confederate inhumanity. The public reaction to Andersonville was overwhelmingly one of anger. The American people had already grown weary of the war and its attendant cruelties. The existence of Andersonville and the inhuman conditions found there inflamed passions and led to demands for retribution.

Survivors of Andersonville faced a long road to recovery. Many former prisoners were not in condition to make the journey home after liberation and had to spend weeks or months at military hospitals and medical facilities. The lack of food and exposure to dysentery and other diseases had caused widespread malnourishment and long-term physical and psychological damage. However, survivor accounts played a significant role in public memory. The horrific stories of Andersonville’s dead line, overcrowding, and starvation were widely reported and shaped public understanding of the prison. Testimonies, such as those of Sergeant Robert H. Kellogg and Dorence Atwater, provided eyewitness accounts documenting the scale of the suffering.

Public reaction to the revelations about Andersonville had lasting political consequences during Reconstruction. The prison’s existence became proof of Confederate atrocity and only emboldened those in the North who wanted to impose harsh conditions during Reconstruction. Some in the South attempted to defend the prison by attributing its deplorable conditions to supply shortages rather than malevolence. This did little to generate sympathy for Confederate leaders in the North, where public sentiment was focused on retribution.

Andersonville became an icon of Confederate inhumanity. Public calls for retribution for Andersonville included the war crimes trial of Henry Wirz. The conditions at Andersonville and the revelations after its liberation galvanized public opinion. It became a symbol of the need for better treatment of prisoners of war in future conflicts and influenced the establishment of international rules and regulations for POWs. As former Union soldiers recounted their experiences at Andersonville, it became a part of a larger national narrative about the Civil War. It ensured that the suffering endured by thousands of men in the prison would not be forgotten.

The Trial of Henry Wirz and Aftermath

As the Civil War drew to a close in 1865, Union officials moved to bring Confederate leaders to justice, and Henry Wirz was among the most notable to be arrested and charged. Wirz, the commandant of the Andersonville prison, was accused of war crimes, including conspiracy to commit murder. Tried in one of the first-ever war crimes trials in the United States, Wirz was a central figure in a case that captivated the nation, with Union and Confederate sympathizers alike following the proceedings closely.

Wirz was tried in Washington, D.C., where over 100 witnesses testified, many of them former inmates of Andersonville who had survived its horrors. They painted a grim picture of starvation, disease, and the deadly Dead Line, and some accused Wirz of ordering executions and personally mistreating prisoners. In contrast, others claimed he had simply been carrying out orders from his superiors. In any event, the testimonies combined to create a portrait of Andersonville under Wirz that made him a lightning rod for the nation’s grappling with the war’s atrocities.

Throughout the trial, Wirz defended himself against the charges, maintaining that he had only been following orders from his superiors and had done his best to improve conditions at the prison, given the resources available. He also claimed that there was nothing he could do about the lack of food, medicine, and shelter at the camp, as the Confederacy’s resources were nearly exhausted by the end of the war. However, the prosecution was unmoved, and the public was outraged, and the trial became less about Wirz himself and more about finding someone to blame for the conditions at Andersonville.

Henry Wirz was found guilty on November 10, 1865, and sentenced to death. He was hanged in Washington, D.C., and became one of the only Confederate officials to be executed for war crimes. His execution was widely publicized, with some seeing him as a scapegoat for the entire Confederate prison system’s failures. In contrast, others saw it as a necessary part of justice for the many who had died at Andersonville. Despite lingering questions about whether he was solely responsible for the prison’s conditions, his trial set a precedent for the prosecution of war crimes and remains a significant moment in American military history.

Andersonville’s Legacy and Memorialization

After the war, Andersonville remained a potent symbol of pain and loss. In 1865, Clara Barton, with the help of former prisoner Dorence Atwater, helped to mark the graves of thousands of soldiers who died there. They were later reburied in consecrated ground with full military honors. An expanded Andersonville National Cemetery was established, and today over 13,000 men lie in marked graves there, as a tribute to those who died behind the stockade. In remembrance and grief, people came to mourn and pay their respects.

Present day Andersonville National Historic Site has the National Prisoner of War Museum. The museum is a more general commemoration and education of American POWs through the ages. By sharing information and experience of survival through exhibits, interviews, and records, a clearer picture of the difficulty and fear soldiers face as prisoners of war through generations is preserved and learned from.

Visiting and studying Andersonville National Historic Site helps to ensure that its legacy will not be forgotten, and that the mistakes of the past are not repeated.

![[Video] Phrase Origins: Mad as a Hatter](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Screenshot-2025-09-30-at-8.00.59-PM-768x512.jpg)

I appreciate the time, research and effort that you put into this. While there are quite a few things that I disagree with (the prison was never liberated; most of the prisoners were sent away in the fall of 1864; Atwater only served as a clerk between June of 1864 and his exchange in Feb, 1865 and the Confederate prison records were also used during the establishment of the National Cemetery, being the only source of records of the deaths after Atwater left), I’m probably best qualified to address the question of the “Renegades,” because I spent years researching them, leading to the publication of the only book to date that deals exclusively with them, “The Andersonville Raiders; Yankee Vs Yankee in the Civil Wars Most Notorious Prison,” published by Stackpole Books in 2022.

Rather than the “Renegades,” most prisoners referred to this group as “Raiders.” There were probably between 80 and 120 of them working in the stockade, and most of them lived in the Southern end of the prison. The raiders had been robbing other prisoners long before Camp Sumter (the official name of the prison at Andersonville) was built, including at Belle Isle and Salisbury (where they were referred to as “Muggers”). The prisoners did fight back against them, and if caught they would be “roughed up” and punished by things like having half of their head and beard shaved as a visual warning to other prisoners or being carried around the prison astride a narrow rail. The prisoners from the Battle of Plymouth had a system in place where, if one of them was accosted, all he had to do was shout “Plymouth!” and any man in earshot who’d been captured there would come rushing to his aid.

But the prisoners from Plymouth also upped the ante, because they’d just been paid before they were captured, including back pay, and they were allowed to keep this money as one of their terms of surrender. This sudden influx of cash, at the beginning of May, 1864, caused the raiders to go from a “nuisance” (prisoner Warren Lee Goss’s word) to a more ruthless, violent, and persistent threat. Things came to a head on June 29th, when an older prisoner named “Dowd” (actually John G. Doud of New York) fought back when four raiders (Delaney, Sarsfield, Sullivan, and Muir) accosted him and beat him within an inch of his life (he never regained his health and died in 1869). Seeing Doud, Henry Wirz demanded that the men responsible be handed over to him and sent in his guards to aid in the arrests. Dozens of men were singled out, so many that Wirz somehow decided which were the “worst” (including the four mentioned above) and ordered the rest to be forced back into the stockade one at a time. They “ran the gauntlet, having to pass through lines of prisoners armed with stick, clubs and whatever else was on hand. One man was killed outright, beaten to death. (If you want to lose sleep, consider that three of the fourteen who were tried were found “Not guilty,” raising the possibility that an innocent man was beaten to death by an angry mob.)

Wirz made the downfall of the raiders possible. He authorized the arrests; provided guards to go in and assist the prisoners in removing accused raiders; held the accused outside the stockade; assisted in the selection of the jury, which was made up of the most recently arrived sergeants on the grounds that they would be the least prejudiced (one of them had only been at the prison eleven days when he was selected as a juror), provided a space for the trial to be held, got authorization from his higher ups to follow through with the jury’s decision to hang six of those found guilty (including the four who’d attacked Doud), and provided the wood and rope for the gallows, personally handing over the men for execution on the evening of July 11th. (There is a story that as he did so, he claimed to have had nothing to do with the proceedings in a speech as he handed the men over to be hanged, but this is not true; this sentence does not appear in any account until John McElroy published his rather sketchy “memoir” in 1879, ever recounting of Wirz’s speech before that omits it.)

My own take on the situation is that the “regulators” who are named in McElroy’s book were likely a rival gang who took advantage of the attack on Doud to eliminate a rival gang – if you look them up in period newspapers, some of them had pretty scary criminal records including convictions or allegations of robbery, attempted murder, extortion and rape, but that’s going to be dealt with in the book I’m working on now.

The day after the raiders were arrested, some of the prisoners who’d been robbed went to the raiders’ tents to try and get their stuff back. When they couldn’t find it, they decided that maybe the raiders had buried it for safe keeping, and so they started digging under their tents. Under one tent, they didn’t find the stolen goods, but instead found two decomposed bodies. You don’t end up dead under someone’s tent in those circumstances unless they put you there, so at least one of the accused raiders not only murdered his would be victims, who presumably tried to resist, but then slept on top of their dead bodies. (I’ve read multiple diaries that relate this, but none identify which raider’s tent it was – I suspect James Sarsfield’s, but have no proof.) So as far as the hanging goes, these guys had it coming.

Thank you so much for sharing your detailed insights and for taking the time to deepen the discussion around Andersonville. We truly appreciate your research and have updated our article to reflect several of your points—such as clarifying that the prison was never “liberated,” noting the transfer of most prisoners in the fall of 1864, and correcting the timeline and role of Atwater. We’ve also refined our discussion on the group historically known as the “Renegades,” now more accurately described as “Raiders,” incorporating the nuances you provided about their numbers, their actions, and the resulting crackdown.

Your comprehensive account—including the specifics of prisoner conflicts, the trial process led by Henry Wirz, and the broader context of these events—has been invaluable in enhancing the historical accuracy of our narrative. We thank you again for contributing to a richer understanding of this complex period in history.