12 Chinese Dynasties Explained: Power, Culture, and Legacy

Chinese dynasties are among the most ancient and longest-lasting in history. For over 4,000 years, various ruling families have presided over the development of Chinese civilization, significantly influencing the course of world history. Chinese dynasties saw the rise and fall of mighty empires, the flourishing of culture and art, and the development of political and philosophical thought. From the Xia to the Qing, these imperial reigns left a lasting mark on the Chinese nation and the world.

China’s dynastic history is a rich and complex tapestry, woven from the lives and deeds of generations of rulers, scholars, and citizens. In this article, we will introduce twelve of China’s most significant dynasties, beginning with the earliest historical records and moving through to the late imperial period. Each dynasty represents a chapter in the long and storied history of the Chinese nation, a civilization that has stood the test of time and left an indelible mark on the world.

Xia Dynasty

Dates: (c. 2070–1600 BCE)

Key Figures: Yu the Great (founder and flood control hero)

Known for: Considered the first Chinese dynasty; flood control and legendary origins

The Xia Dynasty, despite some historical debate, is widely considered China’s first dynasty, marking the transition from prehistory to China’s developed history. This early period is detailed in records written much later in history, including Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian, who wrote that Yu the Great founded the Xia Dynasty. He was known for taming and managing the great floods by dredging and channeling the waters, becoming an example of a moral, just, and effective king.

The Xia Dynasty marked a significant shift from a primitive tribal society to a hereditary monarchy, characterized by a government structure centered on clans and proto-administrative measures that were later formalized in the succeeding dynasties. Some of the early cities, bronze tools, and technology have been discovered, which all show some evidence of increasing centralization of political power and advances in technology.

, palatial structures, bronze vessels, and jade jewelry foundThe Xia dynasty left few records of its existence, but the archaeological site of Erlitou in Henan Province has been identified as a possible Xia Dynasty site due to the size of the city and palatial structures, bronze vessels, and jade jewelry present there. Some modern scholars question the historicity of the Xia. Still, archaeological evidence continues to provide clues that an early and complex society existed, one that could fit the accounts of the Xia Dynasty.

Shang Dynasty

Dates: (c. 1600–1046 BCE)

Key Figures: King Tang (founder), Fu Hao (military general and royal consort)

Known for: Early Chinese writing system, bronze casting, oracle bones, and complex statecraft

The Shang Dynasty is the earliest Chinese dynasty confirmed by historical evidence, largely due to the large number of archaeological findings. The dynasty maintained a centralized government based in the Yellow River Valley, and Shang culture featured a strong monarchy, a hierarchical social structure, and a strong military. They created beautiful bronze artifacts, including ritual vessels, weapons, and tools, which have been found in royal tombs such as those at the last Shang capital, Anyang.

The Shang also left behind oracle bones, pieces of turtle shells, and ox scapulae inscribed with questions about the future, on which the royal family practiced divination. The inscriptions on these bones represent the earliest form of Chinese writing and provide valuable information about the politics, religion, and society of the Shang dynasty. They also indicate the ancestor-based religion that formed the spiritual basis of Shang rule; kings often sought advice from their ancestors on various topics, including the weather, military affairs, hunting, and their own illnesses.

The Shang had a calendar and a certain level of urban planning. Cities like Zhengzhou were protected by enormous earthen walls, indicating both the presence of a central power and the ability to mobilize and direct human resources in a coordinated way. Royal women, such as Fu Hao (whose tomb was found undisturbed), held important positions both in military and religious practices.

After years of corruption, the Shang were eventually overthrown by the Zhou, traditionally around 1046 BCE. The last king of the Shang, Di Xin, is said to have built the over-the-top palace of Shangyangong and was a cruel and lavish ruler who lost the support of both the ordinary people and the aristocracy. He was defeated at the Battle of Muye.

Zhou Dynasty

Dates: (1046–256 BCE)

Key Figures: King Wu (founder), Confucius (philosopher), Laozi (philosopher), Sun Tzu (Chinese military general, strategist, philosopher, and writer)

Known for: Introduction of the Mandate of Heaven, rise of Confucianism and Daoism, and feudal governance

The Zhou Dynasty is the longest-ruling dynasty in Chinese history and a major turning point in Chinese political philosophy and culture. Following their victory against the Shang at the Battle of Muye, the Zhou established the notion of the Mandate of Heaven to legitimize their power. The Mandate, a concept of divine right, became a guiding force in Chinese political thought for millennia to come and would come to justify the cyclical replacement of dynasties.

The dynasty is commonly separated into two eras: the Western Zhou (1046–771 BCE) and Eastern Zhou (770–256 BCE). While the kings of the Western Zhou still exercised a significant centralized power, they were simultaneously governed by feudal states, each ruled by noble families. The central authority began to decline during the Eastern Zhou. This period eventually evolved into the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, characterized by a lack of central power and constant warfare between the states.

The Eastern Zhou period, although very chaotic, is considered one of the most intellectually productive eras in Chinese history. This era witnessed the establishment of numerous primary Chinese philosophical schools of thought, most notably Confucianism, founded by Confucius, and Daoism, which developed around the teachings of Laozi. The Zhou Dynasty also saw a progression in ironworking, agricultural technology, and military innovations like the crossbow.

Qin Dynasty

Dates: (221–206 BCE)

Key Figures: Qin Shi Huang (Emperor), Li Si (Chancellor)

Known for: Unification of China, construction of the first Great Wall, legalist reforms, and the Terracotta Army

The Qin Dynasty was a short-lived yet remarkably influential period in Chinese history. The wars of the Warring States period finally came to an end in 221 BCE, when Qin Shi Huang defeated all his rivals and declared himself the First Emperor of a unified China. The Qin centralized the government, replacing feudal states with a system of provinces directly ruled by officials. They standardized weights, measures, coinage, and even the writing script for efficient and consistent administration.

The Qin Dynasty was greatly influenced by the Legalist school of thought, which called for a strong state, strict laws, and harsh punishments for disobedience. The empire was tightly controlled under Chancellor Li Si, and dissent was ruthlessly suppressed. The most famous of these purges occurred in 213 BCE when the Qin regime burned many classical texts and buried Confucian scholars alive to stamp out intellectual debate.

The Qin invested in infrastructure, such as roads and canals for military movement and trade. They built the foundations of the Great Wall to fend off northern nomadic invaders. The Qin Dynasty is also famous for the discovery of thousands of life-sized Terracotta Warriors guarding the tomb of the First Emperor.

The dynasty fell only a few years after the emperor died in 210 BCE due to public resentment over forced labor, taxes, and the brutal authoritarian regime. The Qin Dynasty nonetheless set an example for centralized imperial rule in China, influencing subsequent dynasties for centuries.

Han Dynasty

Dates: (206 BCE–220 CE)

Key Figures: Emperor Gaozu (Liu Bang), Emperor Wu, Zhang Qian

Known for: Cultural flourishing, expansion of the Silk Road, Confucian state ideology, and technological advances

The Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) was a period of Chinese history that followed the brief Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE). The Han Dynasty is considered a golden age in Chinese history. The Han emperors were led by Liu Bang (the Emperor Gaozu of Han). They humanized the Legalist systems put in place by the Qin. Han rulers adopted Confucianism as the state’s official ideology. The civil service and government became more humane and stable as state bureaucrats were selected through early examinations for civil service.

Emperor Wu (141–87 BCE) was a significant Han ruler who led the expansion of the Chinese military and territorial boundaries. The Han expansion to the west helped secure trade routes that later formed the Silk Road, and Han interactions with Central Asia facilitated the exchange of culture and commerce between China and its neighbors. Zhang Qian, a Han explorer, helped expand diplomatic relationships with these regions and other states throughout Asia.

In addition, Han scientists and technologists have also made significant contributions to China’s development. The seismograph, the wheelbarrow, and papermaking were all developed during the Han era. In the areas of astronomy and medicine, Han scholars and physicians also made significant advances. The latter part of the Han period, also known as the Eastern Han period, saw the creation of the world’s first paper. The invention of paper facilitated record-keeping and bureaucracy in Han China as more people became educated and literate in Chinese history.

Han emperors used the Mandate of Heaven to justify their power over China. This mandate stated that God had granted the right to rule to the Han emperors and that the Han Dynasty was the legitimate government. This effectively sidelined other philosophies, such as Confucianism and Daoism, that did not support the emperor.

The Yellow Turban Rebellion in 184 CE and court corruption that began to reduce the power of the central government were signs of things to come. By 220 CE, the Han Dynasty had weakened and split, marking the beginning of a period in Chinese history known as the Three Kingdoms. Today, many modern Chinese people still identify themselves as the “Han people” due to the enduring influence of the Han Dynasty.

_卷-The_Qianlong_Emperors_Southern_Inspection_Tour_Scroll_Six-_Entering_Suzhou_along_the_Grand_Canal_MET_DP105240.jpg)

Sui Dynasty

Dates: (581–618)

Key Figures: Emperor Wen (Yang Jian), Emperor Yang

Known for: Reunification of China, construction of the Grand Canal, ambitious infrastructure and military campaigns

The Sui Dynasty’s rapid ascension to power in China began as an organized structure with Emperor Wen (Yang Jian) concentrating and centralizing state authority. The legal code was developed, and Confucian civil governance was restored as the Emperor worked hard to create a disciplined bureaucracy. He undertook large-scale construction projects to improve infrastructure and laid the foundation for a period of sustained growth and development.

Emperor Wen focused on reforming and developing trade and transportation by building the Grand Canal, which connected the northern and southern regions of China. The canal was over a thousand miles long, making the transportation of food and goods to the north and southern parts of the country much easier and more efficient. A long-lasting and successful infrastructure investment, it did, however, cause considerable suffering for the laborers involved.

Emperor Wen’s son, Emperor Yang, expanded the Sui Dynasty, focusing on its military might. He is perhaps best remembered for his unsuccessful military campaigns against the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo. Extravagant palace construction, a rise in taxes, and the Emperor’s military campaigns caused widespread suffering among his people, leading to revolts and ultimately the end of the dynasty.

The Sui Dynasty lasted less than four decades. Still, due to their reorganization and restoration of the central administration, the Sui were able to help the Tang Dynasty that followed prosper and build upon a new, and this time long-lasting, unified China. In modern memory, the Sui Dynasty often occupies a transitional place and has been perceived as both brief and significant.

Tang Dynasty

Dates: (618–907)

Key Figures: Emperor Taizong, Empress Wu Zetian, Emperor Xuanzong

Known for: Cultural flourishing, expansion of trade via the Silk Road, and cosmopolitan governance

The Tang Dynasty is often celebrated as the golden age of Chinese civilization, renowned for its cultural, technological, and diplomatic accomplishments. Founded by Emperor Gaozu in 618, the dynasty reached its zenith under his son, Emperor Taizong, who centralized authority, codified laws, and expanded the empire’s borders into Central Asia. Taizong’s reign was marked by political stability, military might, and administrative efficiency.

The Tang era also produced several influential figures, such as Empress Wu Zetian, the only woman in Chinese history to claim the title of emperor. Her rule was contentious but significant in promoting meritocracy and advancing Buddhism’s status within the empire. Wu Zetian’s reign challenged traditional gender roles and left a profound impact on Chinese court politics and governance.

The Tang capital, Chang’an, was a bustling metropolis that attracted merchants, diplomats, and scholars from Persia, India, Arabia, and other parts of Asia, fostering a rich multicultural environment alongside Chinese elites. The dynasty also witnessed the emergence of literary giants like Li Bai and Du Fu, whose poetry became emblematic of classical Chinese literature and remains revered today.

However, the dynasty was eventually undermined by corruption, rebellion, and the rise of regional warlordism. The catastrophic An Lushan Rebellion, which lasted from 755 to 763, set the stage for the dynasty’s decline, resulting in the loss of millions of lives and leaving the empire in a state of disarray. Although the Tang Dynasty eventually fell in 907, its cultural and administrative innovations continued to shape East Asia and the world for centuries.

Song Dynasty

Dates: (960–1279)

Key Figures: Emperor Taizu (Zhao Kuangyin), Su Song, Shen Kuo

Known for: Scientific and technological innovation, economic prosperity, and urban expansion

The Song Dynasty is recognized as one of the most intellectually and economically developed eras in Chinese history. It was established by Emperor Taizu in 960 after a prolonged period of disunity and prioritized civil administration and bureaucracy over military strength. The Song era was a period of significant scholarly development and urban expansion, with Kaifeng and later Hangzhou becoming two of the world’s largest and most cosmopolitan cities.

During the Song Dynasty, a vibrant culture of technological and engineering advancement emerged. The Chinese invented movable-type printing, which improved the accessibility of books and the reliability of record-keeping. In addition, advances in navigation, including the use of the magnetic compass, as well as developments in astronomy and cartography, enabled trade and exploration. Engineer and scientist Su Song also constructed a massive water-powered astronomical clock tower during the Song period.

The Song period also witnessed a significant increase in economic output, driven by a highly developed market economy. Paper currency became increasingly common, and agricultural practices improved with the introduction of fast-ripening rice from Vietnam, supporting a growing population. The Song also promoted Neo-Confucianism, a movement that had a lasting impact on Chinese society and government.

The Song’s military weakness led to its territorial losses to external enemies. The dynasty was forced to cede control of northern China to the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty and was later overthrown by the Mongols under Kublai Khan in 1279. Despite the military decline of the Song, its cultural and intellectual achievements had a lasting impact on Chinese civilization.

Yuan Dynasty

Dates: (1271–1368)

Key Figures: Kublai Khan (Emperor), Marco Polo (visitor)

Known for: Establishing Mongol rule over China and expanding international trade along the Silk Road

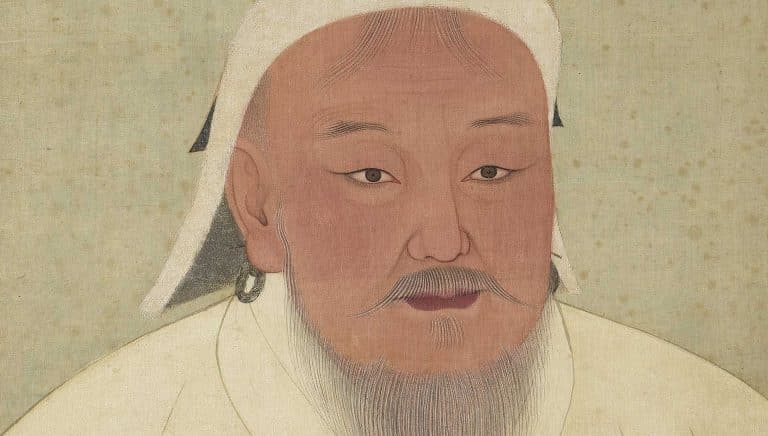

The Yuan Dynasty was established by the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, and it came to power following his conquest of the Southern Song in 1279. It was the first time that all of China was controlled by a non-Han dynasty. The Yuan court integrated many Chinese traditions and imposed Mongol culture on China, but it also retained its own Mongol identity, creating a complex fusion of cultures. Kublai Khan formally established the Yuan Dynasty in 1271 and moved the capital to Dadu (Beijing).

The Yuan Dynasty is best known for its contributions to global trade and cultural exchange. The Mongol Empire established connections across its vast territory, enabling merchants, diplomats, and travelers to travel from Europe to Asia with greater ease than ever before. The Venetian explorer Marco Polo visited the court of Kublai Khan and described the wealth and sophistication of China in his writings, which captured the imagination of Europe.

However, the Yuan Dynasty faced significant challenges during its rule. The Mongols encountered resistance from the native Chinese, who resented their rule. Natural disasters, corruption, and heavy taxation led to widespread unrest. The ethnic divide between the Mongols and the Han Chinese was institutionalized, with the Mongols at the top of the social hierarchy and the Han Chinese at the bottom. These factors contributed to the weakening of the Yuan Dynasty over time.

The Yuan eventually lost the Mandate of Heaven as peasant rebellions spread across the country. The Red Turban Rebellion eventually led to the rise of Zhu Yuanzhang, who overthrew the Yuan Dynasty and established the Ming Dynasty. Although the Yuan Dynasty was short-lived, it left a lasting legacy in the development of the capital city and in China’s engagement with the world.

Ming Dynasty

Dates: (1368–1644)

Key Figures: Zhu Yuanzhang (Emperor Hongwu), Zheng He (admiral)

Known for: Cultural renaissance, naval expeditions, and the construction of the Great Wall’s iconic sections

The Ming Dynasty was founded when Zhu Yuanzhang, a former Buddhist monk and rebel leader, overthrew the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty in 1368. Zhu, who became Emperor Hongwu, focused on agrarian reform, Confucian orthodoxy, and a strong centralized bureaucracy. After nearly a century of foreign rule, his government prioritized re-establishing Han Chinese rule and traditional Chinese values.

The Ming era is also notable for its exploration and global trade, especially in the early 15th century. Admiral Zheng He led large fleets of treasure ships on voyages as far as East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. These expeditions demonstrated Chinese naval power and expanded diplomatic and trade relations throughout Asia and beyond.

Domestically, the Ming is known for its large-scale architectural projects, including the construction of the Forbidden City in Beijing. Chinese literature, porcelain production, and Confucian scholarship thrived. The dynasty also engaged in significant military campaigns to protect China’s northern borders and much of the Great Wall as it is seen today was built during this period.

The Ming Dynasty eventually encountered numerous problems, including corruption, peasant rebellions, and an inflexible bureaucracy. These issues, combined with natural disasters, fiscal difficulties, and military failures, led to the dynasty’s decline. In the mid-17th century, rebel leader Li Zicheng captured Beijing, and the last Ming emperor, Chongzhen, committed suicide. The Manchu-led Qing Dynasty subsequently rose to power in 1644.

Qing Dynasty

Dates: (1644–1912)

Key Figures: Kangxi (Emperor), Qianlong (Emperor), Empress Dowager Cixi

Known for: Last imperial dynasty, territorial expansion, cultural flourishing, and eventual decline under foreign pressure

The Qing Dynasty was founded by the Manchu ethnic group, which invaded China and overthrew the Ming Dynasty. Initially seen as foreign conquerors, the Qing established firm control over China, and through effective leadership and Confucian policies, they gained support from most of the Han Chinese majority. Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661–1722) and his grandson, Qianlong (r. 1735–1796) reigned over a golden age of relative peace and prosperity, during which China experienced economic development and territorial expansion, conquering Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia.

The Qing era also saw the continued development of Chinese literature, art, and philosophy. The civil service examination system remained in place, and numerous major literary projects were completed, most notably the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries. China was among the most populous and prosperous nations in the world.

The dynasty was less able to adapt to the accelerating changes in the world around them. By the 19th century, internal corruption, population growth, and weakened leadership had made the Qing vulnerable to outside influence. The Qing were defeated in a series of humiliating military conflicts known as the Opium Wars, and China was forced to sign unequal treaties with Western powers. Later rebellions, most notably the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) and the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), would also weaken the state.

Empress Dowager Cixi would later dominate the late Qing. Although there were attempts to reform and modernize the government and society along Western lines, by this point, the dynasty was too weak. The dynasty ended in 1912 after the Xinhai Revolution, which overthrew the imperial system that had ruled China for over 2,000 years. This ushered in the period of republican China under the Republic of China.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Chinese Dynasties

The History of the Chinese Dynasties is a saga of remarkable endurance, innovation, and cultural richness. Over millennia, dynasties from the semi-legendary Xia to the mighty Qing have left indelible marks on the nation’s identity. These ruling houses presided over the construction of walls, canals, philosophies, and revolutions, weaving a civilization that has influenced the world for over four thousand years. They faced invasions, internal rebellions, and periods of golden ages in art and science.

Even though dynastic rule ended with the fall of the Qing in 1912, the legacy of these Chinese dynasties continues to echo in China’s modern institutions, cultural pride, and political identity. Understanding their rise and fall offers critical insight into the country’s enduring resilience and evolving global role.

![𝐂𝐡𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐠 𝐊𝐚𝐢-𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐤 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐂𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐚’𝐬 𝐖𝐚𝐫 𝐄𝐟𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐭 – 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐅𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐨𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐧 𝐅𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐭 [VIDEO]](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Screenshot-2025-02-19-at-8.42.39 AM-768x512.jpg)