Chaos in New York: The Deadly Draft Riots of 1863

In July 1863, just as the Union army was winning a decisive victory at Gettysburg, the streets of New York City were in chaos. The New York City Draft Riots, from July 13 to July 16, 1863, would become one of the deadliest incidents of civil unrest in American history. Working-class anger over the Union’s Enrollment Act, which allowed the wealthy to buy exemption from military service, boiled over into violence. Irish immigrants, fearing competition from freed Black workers and angered by the war’s progress, led mobs that attacked draft offices, homes, and neighborhoods.

The riots exposed the dangerous mix of class, racial, and war-related tensions in Northern society. African American New Yorkers were among the main targets—lynched, beaten, and forced out of their homes. Federal troops, returning from Gettysburg, had to restore order, leaving over 100 people dead and the city’s neighborhoods deeply scarred. The Draft Riots were more than just an anti-draft protest; they revealed deep divisions within the Union and the high cost of a war fought on both military and moral grounds.

Background to the Riots

By 1863, the American Civil War was taking a toll on life in New York City. The conflict was now in its third year, and economic conditions, war weariness, and increasing casualties and political divisions created an atmosphere ripe for political violence. Class tensions were high in New York’s working-class neighborhoods, and Irish immigrants in particular were angry and alienated. Many were working low-paying, physically demanding jobs, and faced prejudice from both nativists and other social and political institutions. The implementation of new federal policies, with the war, added to the growing sense of injustice and inequality.

Fear of economic displacement was at the core of the grievances that led to the Draft Riots. Many white working-class people believed that the freeing of enslaved Black people in the South would result in the influx of free Black workers in the North who would compete for jobs and resources and lower wages. The New York press and some local politicians fanned the flames of class conflict and racial animosity by stoking fears of Black people in the labor force. Irish neighborhoods in particular felt that they were being asked to fight and die in a war that would make their economic situation worse.

Race relations in the city were already strained before the war began. The city had significant financial interests in the South, and not all New Yorkers supported Lincoln’s plans for abolition. As emancipation became a war aim, these tensions only increased. The Irish in New York City were the fastest-growing ethnic group and were fighting to establish themselves economically. Black New Yorkers were often seen as competition for jobs and economic advancement for the Irish and other working-class people in the city. Racist as this may have been, the perception was sometimes used as a wedge by political elites and politicians to stoke resentment between poor people.

The situation on the ground in the city quickly boiled over as the war began to affect the home front. Federal measures to increase troop numbers and provide support to the war effort were often seen as punitive and unjust by New York’s working class. While the policies were aimed at the national good of the union and survival, the result in New York City was an explosive combination of class resentment, economic anxiety, and racial animosity that exploded in the most deadly urban riot in American history.

The Spark: Draft Lottery Begins

New York City on July 11, 1863, was in a mood of high anxiety. The federal government was conducting the first lottery of names of men eligible for military service under the Enrollment Act. Names were being drawn in public at the Provost Marshal’s office on Third Avenue and 47th Street. Although it passed off in relative calm, the draft lottery would unleash a torrent of working-class fury and racist violence across the city in the coming days.

The draft had been hated from the start, with good reason. As the wealthy class could pay a $300 commutation fee to avoid service, it was rightly seen by many as the rich man’s war.

Unease and anger were dominant moods over the weekend after the draft. Crowds started to gather in working-class neighborhoods already simmering with rage. People spoke of large groups enlisting en masse, or even the unfair selection of men. Neighborhood meetings turned into angry calls to action, and local leaders were blunt that the situation could not continue in the city with the draft going forward. There was a sense of profound injustice. For many men who were living hand to mouth, the draft was a death sentence to be sent to a war that had seemingly little to offer to them.

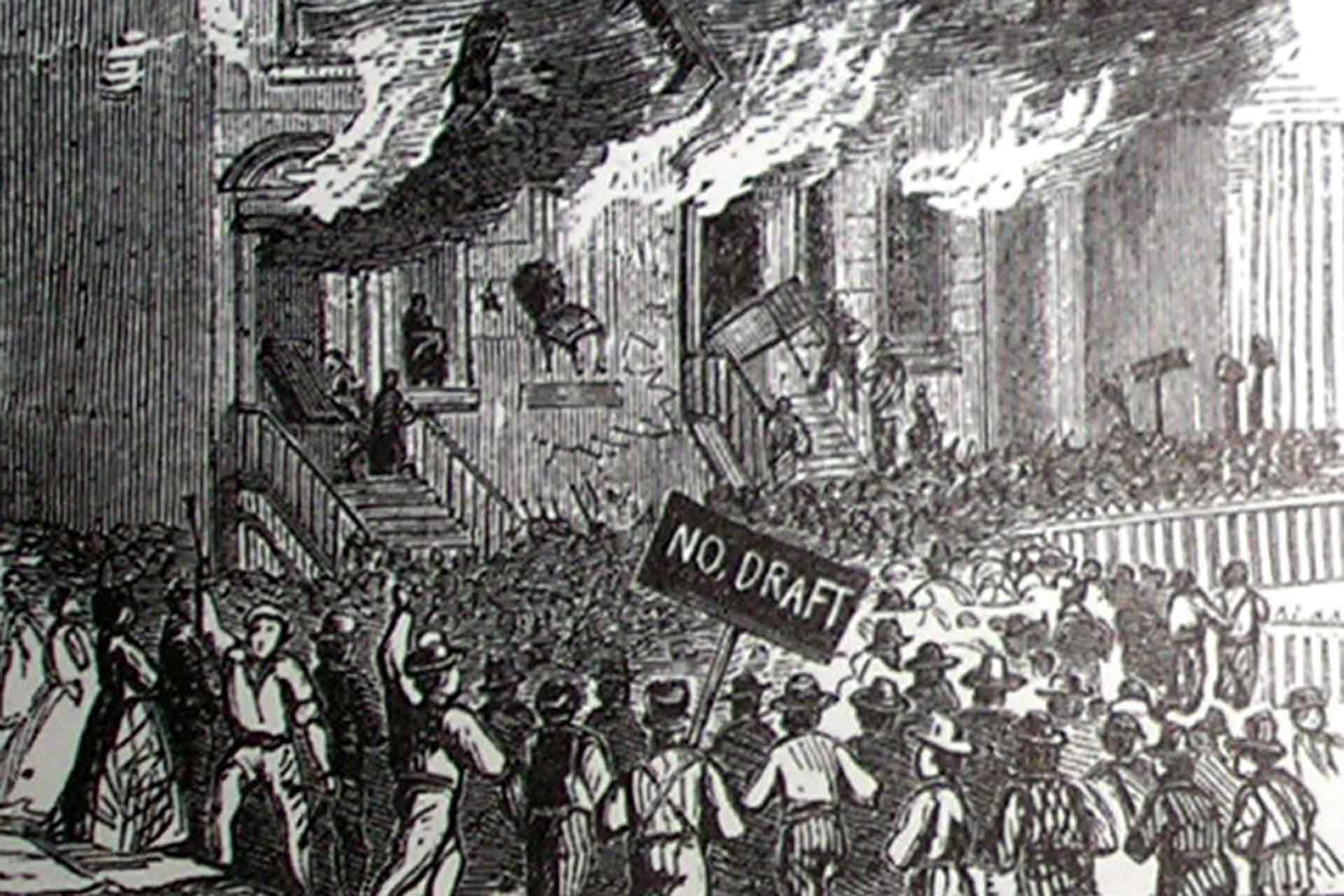

This came to a head in the early morning hours of July 13. A large crowd of men and boys was milling around in front of the Provost Marshal’s office just as the second day of the draft lottery was about to begin. A sudden anger took over, and they stormed the building, overrunning the small security force in minutes. Draft records were seized and burned, furniture overturned, and the building set on fire. What had started as a political protest against the draft turned into generalized mayhem.

This initial foray would be the start of four days of chaos and bloodshed across the city. The destruction of draft records was not merely a statement of resistance; it was an attack on federal authority. As the building burned and crowds grew in size and anger, it was only a matter of time before their ire was turned to other government buildings, businesses, and then increasingly, Black residents. The delicate social order had been broken, and the worst urban violence in American history was about to begin.

Days of Violence

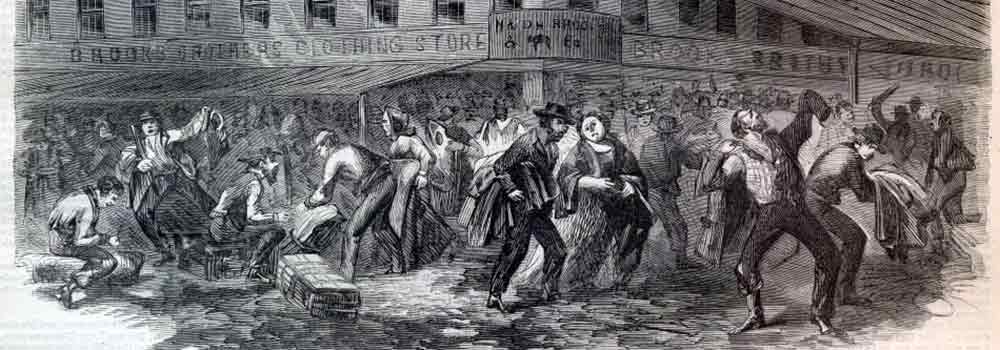

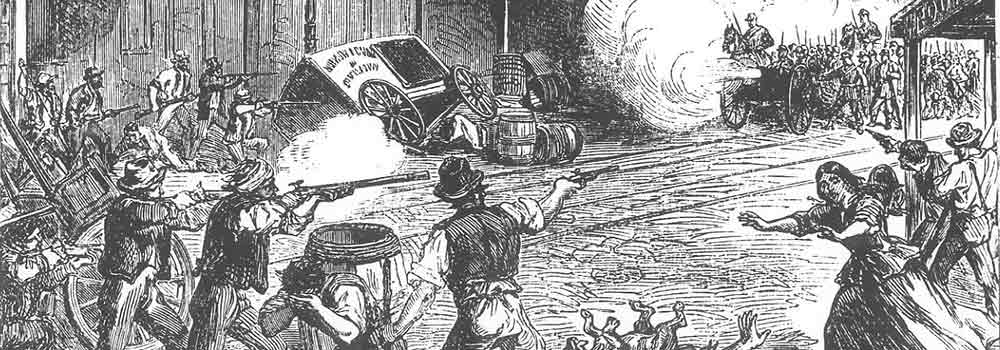

Fire engulfed the draft office. The violence soon spread to other parts of Manhattan. The draft riot began as a protest against conscription but quickly escalated into a full-blown riot. Groups of people looted and burned homes, businesses, and telegraph wires in a brazen effort to sever communications with federal officials. Rioters targeted government buildings and any location they associated with Republican or abolitionist sentiments. Fires raged through parts of Manhattan as many buildings were deliberately set ablaze.

Black people were the primary targets of the mob’s violence. White rioters ransacked neighborhoods and hunted down African American men, women, and even children. In one of the most notorious incidents, a mob lynched a 12-year-old boy named Abraham Franklin, mutilating his body and leaving it on display. Dozens of other Black men and women were attacked, beaten, and murdered. The violence was indiscriminate, but underscored by intense racism and economic anxiety.

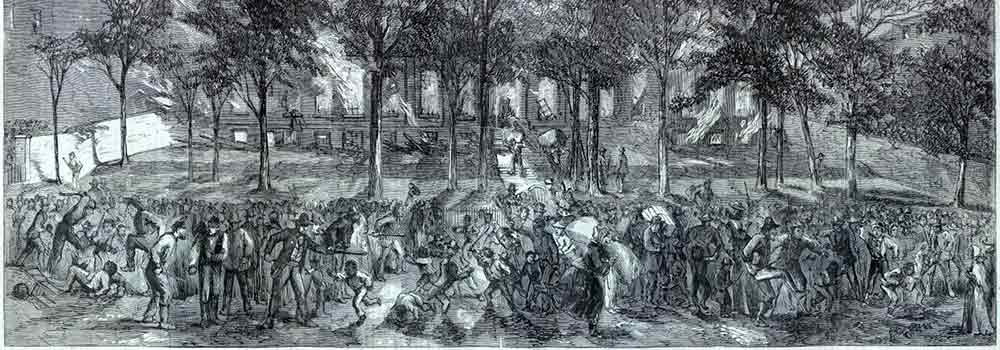

The Colored Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue was one of the most infamous scenes of violence during the riots. At the time, the orphanage was home to over 200 Black children. Rioters looted the building and set it on fire on July 13. Staff and bystanders helped the children escape unharmed. The burning of the orphanage was seen as one of the most egregious acts of violence during the riots, as the mob targeted the very institution that was meant to provide safety and security for Black children.

The New York Police Department, led by Superintendent John Kennedy, struggled to control the situation. At first, officers tried to hold back the rioters without drawing their weapons. However, the NYPD was quickly overwhelmed by the sheer number of rioters. Kennedy was nearly killed while trying to disperse a mob at Five Points. The police fought block by block and fired into the crowd in some instances. Police often had to use clubs and their revolvers to defend their stations and protect citizens. However, their actions did little to impede the rioters’ advance during the height of the violence.

Firefighting crews would not respond to fires started by the mob, either out of fear or sympathy for the rioters. White abolitionists and Republican politicians went into hiding. Black residents would flee to outlying parts of the city or to nearby police stations, churches, or military installations for safety. For three days, New York City appeared to be on the verge of collapse, as class resentment and racism boiled over.

Government Response and Military Intervention

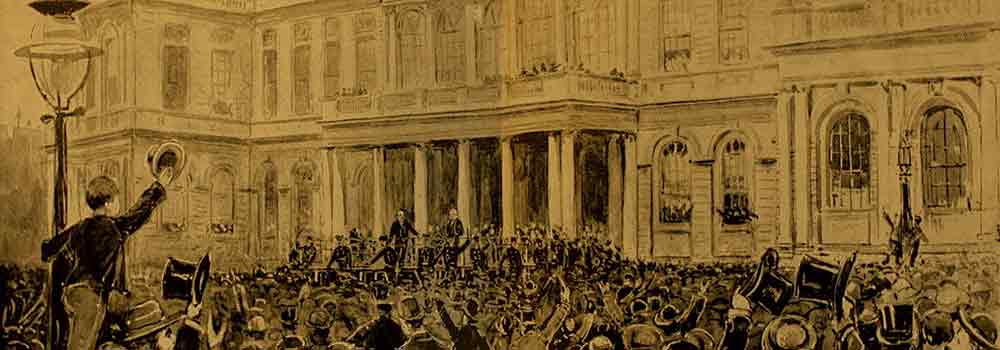

The violence of the Draft Riots spread through Manhattan as the municipal and state leadership of New York City seemed to be frozen. Mayor George Opdyke and New York Governor Horatio Seymour both refused to take strong action early in the crisis. Seymour personally attempted to placate the rioters by giving a speech in which he referred to them as “my friends”. In retrospect, this gesture was seen as pandering to the mob. The city officials’ failure to quickly and forcefully restore order allowed the insurrection to spread through Manhattan.

President Abraham Lincoln, alarmed by telegraphic reports of an increasingly out-of-control situation, ordered Union army regiments to deploy to New York City. As these troops were still only a few days removed from their Gettysburg victory, the 152nd New York and the 7th Regiment were among the regiments that were ordered to New York. They began to arrive on July 16.

The mob that gathered in response to the first deployment of the troops was fired upon with volleys, which in turn were answered by rifle fire from the rioters. The Union soldiers, tired as they were from the battlefields, were ordered to clear all the streets, and several gun battles took place. Armed resistance met organized military might, and the order was restored to the streets of New York City.

Telegraph lines were repaired, and in Manhattan, several regiments were put on patrol through the city, many with fixed bayonets. Others were ordered to take key positions in Washington Heights and Harlem, or to the south at Fort Wood at the center of Manhattan. Protected by bayonets, rifle and artillery fire, the troops took back all of the key street intersections and bridges, and closed in on the looters and remnants of the mob. By the night of July 16, the military had reestablished control of the city, and the rioting had ended.

Aftermath and Legacy of the Draft Riots of 1863

The toll on New York City from the Draft Riots was severe and long-lasting. The exact number of casualties remains a matter of some debate, with various sources and historians offering estimates. While lower numbers are often reported, a consensus among historians suggests that the death toll was at least 120, with some estimates going higher.

In terms of property damage, estimates at the time placed the cost at about $1.5 million in 1863, which would equate to over $45 million in today’s money. Hundreds of buildings were damaged or destroyed during the riots, including institutions like the Colored Orphan Asylum. The city’s infrastructure was significantly disrupted, with telegraph lines down and public transit inoperable for several days following the riots.

The African American community in New York City was devastated by the Draft Riots. In the immediate aftermath, many black New Yorkers fled the city, and institutions and neighborhoods were destroyed or looted. The black population of the city decreased sharply in the years following the riots, not recovering its pre-riot numbers until decades later.

The political repercussions of the Draft Riots were significant for New York City and the wider United States. The Democratic Party in New York, particularly the Tammany Hall political machine, suffered due to its perceived anti-war and anti-draft stance. However, its influence would rebound in later years. The Republican Party leveraged the riots as an example of the dangers of dissent and the necessity of a determined national effort. The riots exposed the fragility of Northern cities to the war’s social and economic pressures and highlighted the racial and class tensions simmering within Union territory.

Public opinion in the North was influenced by the events in New York. For some, the riots were a wake-up call to the true nature of the Civil War as a struggle not just for union but for social and economic equality. There was an increase in support for emancipation among certain segments of the population, while others became more resolute in their opposition to the war. The uprising added complexity to the narrative of a united North, revealing underlying divisions and resentments.

In the decades following the Draft Riots, the memory of the event was marked by shame and, at times, by deliberate silence. Few, if any, monuments or memorials were erected to commemorate the event. Survivors, especially Black New Yorkers, received little in the way of public support or acknowledgment in the rebuilding process. It wasn’t until more recent historical efforts and scholarship that the full extent of the violence and its victims received proper recognition, ensuring that the events of July 1863 were not forgotten. The legacy of the Draft Riots continues to shape discussions on race, protest, and the costs of civil conflict.

Conclusion: Unrest Beneath the Union Banner

The Draft Riots of 1863 exposed the underbelly of Northern society. A war ostensibly fought for union and freedom had splintered New York City along racial, class, and cultural lines. Beneath the Union flags and the talk of freedom were deep-seated grievances of race, inequality, and fear. The Draft Riots were a violent expression of social discontent, where long-standing resentment against the wealthy elite and newly freed African Americans boiled over into chaos.

The Draft Riots are a domestic reminder that the Civil War was not only a battle for the southern states but also a fight for justice on American soil. The echoes of the Draft Riots resonate today in the tension between resistance and reform, the ongoing struggle for racial equality, and the process of reckoning with America’s divided history.