The Plantagenet Kings of England: 300 Years That Shaped a Nation

The Plantagenet Kings of England ruled for over 300 years and shaped the future of the British monarchy, the legal system, and the English identity. From the ascension of Henry II in 1154 to Richard III’s fall at Bosworth Field in 1485, the Plantagenet dynasty saw the rise of common law, civil wars, and the Hundred Years’ War. Through turbulent times and a cast of larger-than-life characters, intrigue, and ambition, the Plantagenets laid the foundations of modern England, a legacy still evident today.

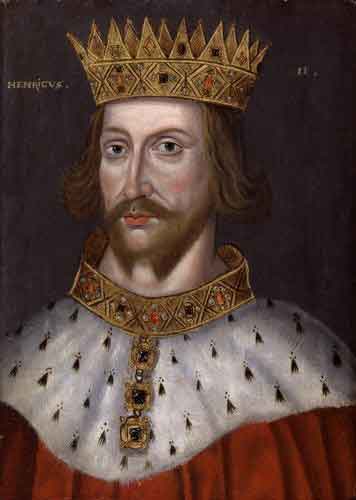

Henry II: Foundations of a Dynasty

Reign as King of England: 1154–1889

Spouse: Eleanor of Aquitaine

Legacy: First Plantagenet king; established the dynasty after the civil war known as The Anarchy.

Birthplace: Le Mans, France

Henry II ascended to the English throne in 1154 after a period of civil war and baronial discord had left the kingdom in disarray. The first king of the Plantagenet dynasty, Henry, wasted no time consolidating power, reasserting royal control over the government, and expanding the crown’s influence. As Duke of Normandy and Anjou, through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry also ruled extensive lands in France, and his domains would become known as the Angevin Empire. As a ruler, he was one of the most powerful in Western Europe.

Henry’s greatest legacy was in the administration of the law. He reorganized the English courts, established royal justice, and sent judges on circuits across the land, the basis for common law in England. Henry’s reforms would take priority over feudal and ecclesiastical law, bringing a measure of consistency to the realm. The historian W.L. Warren said of Henry: “Henry II was not only a monarch, he was a builder of institutions.” Henry II’s legal innovations would endure for centuries in England and around the world.

Henry’s reign was not without its drama. He famously quarreled with his Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, over the church’s rights. After a fit of pique, he supposedly uttered the fateful words: “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?” Upon hearing the king’s words, four knights acting on their own initiative murdered Becket in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170. The murder caused an outcry across Europe, and Henry was forced to do public penance in the cathedral. He was also severely embarrassed, and his reputation was forever tarnished.

Henry’s family proved difficult to control as well. Henry’s wife, Eleanor, and his sons, the future kings Richard I and John, were in almost constant rebellion against him. They were all upset at Henry’s hesitancy to fully share power with them. Despite the many trials and tribulations of his personal life, Henry II remained in control until he died in 1189 and passed the crown to his son Richard I. Henry II was the first of a royal house that would rule for three hundred years.

Richard I

“the Lionheart”: Warrior King of a Distant Throne

Reign as King of England: 1189–1199

Spouse: Berengaria of Navarre

Legacy: Famed for his role in the Crusades; spent most of his reign abroad fighting in the Holy Land.

Birthplace: Oxford, England

Richard I, known as “the Lionheart,” was crowned in 1189. He was reputed to be a courageous and martial king who was deeply devoted to the Crusades. In contrast to his father, Henry II, he had little interest in ruling England. Richard saw the kingdom as a convenient source of funds to finance his military adventures, and once suggested he would sell London if he could find a buyer. He spent less than six months in England during his ten-year reign, earning his reputation on the battlefields of the Holy Land.

Richard’s reign is best known for the Third Crusade, which was called in response to Saladin’s capture of Jerusalem. Richard enjoyed a series of victories, culminating in the capture of Acre and the Battle of Arsuf in 1191. His personal bravery and military leadership earned him respect from both friends and foes—Saladin reportedly admired Richard’s courage. However, despite his efforts, Richard was unable to recapture Jerusalem. A truce was negotiated in 1192 that allowed Christian pilgrims to visit the holy city, but Jerusalem itself remained under Muslim control.

While returning from the Holy Land, Richard was captured near Vienna by Duke Leopold of Austria, to whom he had previously offended during the Crusade. The duke transferred Richard to the Holy Roman Emperor, who held him for ransom. England had to pay a vast sum to secure his release, equal to several years’ worth of royal income, which caused resentment among his subjects. His long absence also gave various factions room to jockey for power, including his brother John.

Richard returned to England briefly, then set off again for military campaigns in France, where he would spend the final years of his life. He died in 1199 of a wound received during a siege in Limousin. His last words are said to have been a recognition of his defeat by a common crossbowman: “I die by the hand of one not worthy to be a knight.”

Richard I became an iconic figure in medieval chivalry and crusading heroism. His reign did little to ease or reform the country’s internal situation. In some ways, he was the ideal medieval king, who gained the status of legend both as a hero and as an absentee ruler.

King John:

A Reign of Crisis and Consequence

Reign as King of England: 1199–1216

Spouse: Isabella of Angoulême

Legacy: Infamous for losing Normandy and signing the Magna Carta under baronial pressure.

Birthplace: Oxford, England

John ascended to the throne in 1199 after the death of his elder brother Richard the Lionheart. He was a less charismatic and politically astute ruler, unlike Richard, who was a military leader. Historians quickly tagged him as a king notorious for his cruelty, untrustworthiness, and general ineptitude. He rapidly lost the Angevin Empire’s possessions in France, especially Normandy, to King Philip II of France in the first few years of his reign. This shamed the English crown and reduced its influence abroad, while also undermining John’s authority at home in the eyes of the nobility.

In his efforts to raise money for an attempted reconquest, John imposed arbitrary and burdensome taxes and fines, sowing discontent at all levels of society. The baronial resistance to his rule simmered, then boiled over as the self-styled “Leo” engaged in repeated legal disputes with principal nobles. This eventually culminated in the revolt of the barons, as John failed to achieve his military and financial objectives, imposing an unpopular tax known as scutage, a tax paid by a knight instead of military service, and even falsifying justice to put down his critics. He earned the sobriquet “Lackland” from contemporaneous chroniclers, as well as “Softsword”.

In 1215, the barons rebelled against John, and he was forced to agree to a document called Magna Carta (or “Great Charter”) at Runnymede that effectively limited royal power, while also subjecting it to the law, as no one, not even the king, was above the law. The charter, however, was annulled a few months later by the Pope at John’s request. After John’s death, it was reissued by his son and successor, Henry III, and became the foundation of English constitutional law. The 13th-century chronicler Matthew Paris described John as “a tyrant rather than a king”, and his reign left a deep impression on contemporaries.

His reign was also marked by conflict with the church. England was placed under interdict in 1208, and Pope Innocent III excommunicated him in 1209. The dispute only ended when John surrendered and acknowledged England as a papal fief, re-establishing cordial relations with the papacy, but doing nothing to endear him to his subjects.

John died in 1216, when his son, Henry III, was nine years old, as the country was ravaged by civil war, and on the brink of invasion by Prince Louis of France. His reign was widely seen as a failure at the time, but recent revisionist historians have somewhat rehabilitated John’s reputation. The crisis of this Plantagenet king’s reign is seen as a key moment that forced English rulers to operate within constraints and redefined the idea of monarchy in England.

Henry III:

The Devout Plantagenet King and the Seeds of Parliament

Reign as King of England: 1216–1272 Spouse: Eleanor of Provence

Legacy: His long reign saw baronial unrest and the rise of parliamentary power in England.

Birthplace: Winchester, England

Henry III was only nine when he became king in 1216. At this time, the country was in a perilous state, lacking clear leadership following the turmoil of civil war and foreign invasion. Henry’s reign was at first guided by regents such as William Marshal, and the reissue of the Magna Carta restored some trust between the king and the barons. Henry III took personal rule in 1227 and became a pious king who invested much in the church and the arts. He is well known for the rebuilding of Westminster Abbey in the Gothic style.

Henry spent a long time on the throne (for medieval England); however, he was often at odds with the barons and was unwise in his choice of advisors and his favoritism towards his wife’s Savoyard relatives. His financial extravagance and general unpopularity amongst much of the English nobility troubled him throughout his reign. Although his father had clashed with the barons and the legacy of Magna Carta, Henry III often ignored the restrictions on royal power, with long-term consequences for his inaction.

Henry was forced to accept the Provisions of Oxford in 1258, a plan that had been drawn up by a group of barons led by Simon de Montfort. It required that a council of barons oversee the execution of certain royal powers. This acceptance marked a turning point in Henry’s rule; he later repudiated the Provisions, and this led to the Second Barons’ War. In 1264, de Montfort’s army defeated the king at the Battle of Lewes and set up a radical new form of government that included representatives from the towns. This has been considered the first Parliament in history.

Henry was restored to the throne after the Battle of Evesham in 1265, when his son Edward (later Edward I) killed de Montfort and put down the rebellion. Henry was restored, but in a weakened position, and his rule was never the same. He was never able to get around the continuing importance of Parliament. Henry III’s character and conduct of government are generally seen as weak and indecisive, but they were a necessary phase in the evolution of the constitutional monarchy. This was a key time for setting out the balance of power between monarch and subject, even if most of it was done without Henry’s involvement.

The long reign of Henry III oversaw the gradual growth in parliamentary power. Matthew Paris, the contemporary chronicler, often highly critical of the Plantagenet king’s personal actions, allowed that Henry was a man “devoted to the service of God and the seeking of learning”.

Edward I: The Lawgiver and the Conqueror

Reign as King of England: 1272–1307

Spouse: Eleanor of Castile

Legacy: Known as the “Hammer of the Scots” and a reformer of English law.

Birthplace: Westminster, England

Edward I, crowned in 1272, stands out as one of the most powerful and effective rulers among the Plantagenet Kings. A robust and imposing figure with a talent for military strategy, Edward was a fierce warrior, most infamously known as the “Hammer of the Scots.” Prior to his ascension to the throne, Edward demonstrated leadership and competence during the Barons’ War, backing his father, Henry III. His victory at the Battle of Evesham was instrumental in overcoming Simon de Montfort and restoring his father’s power.

As king, Edward I’s reign was marked by his desire to centralize power and reform laws, governing with an iron fist. A significant achievement was his reform and restructuring of English law, culminating in a series of legal statutes. These laws, including the Statute of Westminster and the Statute of Mortmain, standardized justice across England and expanded royal authority over land ownership and legal administration. For these monumental legal reforms, later generations named Edward the “English Justinian.” In particular, Edward’s legal legacy lives on in the creation of standard law.

Edward was also intent on expanding and securing his realm through military conquest. One of his most notable successes was in Wales, where he commissioned a series of formidable stone castles, including the iconic Caernarfon and Conwy, and brought the Welsh crown under the English king. Edward’s conquest of Wales was marked by violence and ruthlessness, yet it was ultimately a resounding success. He even took to creating the title of “Prince of Wales” to be bestowed upon the future king’s eldest son.

Edward also sought to extend his influence over Scotland, leading to decades of brutal warfare. The Scottish king’s death led to Edward laying claim to overlordship of Scotland and the right to determine its succession. This overreach sparked open conflict, and Edward would fight William Wallace and, later, Robert the Bruce for control of Scotland. The Scottish campaigns were both costly and protracted; Edward I won many battles but never truly crushed his enemy. He died in 1307, still at war with Scotland. Edward’s tenacity and stubbornness in this conflict, however, would have a lasting impact on Anglo-Scottish relations.

King Edward I’s reign set a stronger precedent for royal authority and a more unified England. While a harsh and authoritarian ruler, Edward I was also a deeply strategic leader whose commitment to law and conquest would shape the future of the Plantagenet line. As such, Edward I is rightly seen as one of the great kings of medieval England.

Edward II:

A Troubled Reign & a King Unseated

Reign as King of England: 1307–1327 Spouse: Isabella of France

Legacy: A weak and controversial ruler, deposed by his wife and her lover. Birthplace: Caernarfon, Wales

Edward II ascended the throne in 1307 upon the death of his father, Edward I. The former king had been a powerful and respected figure, setting the stage for a challenging transition. Unlike his father, Edward II was not equipped with the political acumen or the military discipline that were hallmarks of medieval kingship. His immediate problem was his reputation: from the moment he took the throne, he was associated with favorites like Piers Gaveston, whose close relationship with the king was deeply resented by many powerful nobles. Gaveston’s perceived arrogance and the privileges he received as a favorite rankled the barons, ultimately leading to his execution in 1312, an act that Edward failed to prevent or avenge.

The most significant military blunder of Edward II’s reign was the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. The Scots decisively defeated his forces under Robert the Bruce. This defeat was not only a humiliation but a disaster for English prestige and military morale. It also confirmed Scottish independence for a generation, leaving Edward’s leadership in tatters. Chronicles from the period criticize Edward for his perceived cowardice and ineffectiveness, with some chroniclers noting the “indolence and disorder” that marked his reign, reflecting his inability to control his nobility or inspire loyalty through competence.

In the latter part of his reign, Edward’s reliance on the Despenser family as royal advisors and close confidants once again inflamed baronial dissent. When Edward again failed to address his barons’ concerns, a rebellion ensued, leading to a period of civil unrest and the weakening of royal authority. In 1326, his queen, Isabella, and her lover, Roger Mortimer, invaded England. In an unprecedented move in English history, Edward was forced to abdicate the throne in favor of his 14-year-old son, Edward III. The deposition of a reigning king was a clear indication of how low royal prestige had sunk by the end of Edward II’s rule.

Edward II was imprisoned and, in a likely conspiracy, later died under mysterious circumstances at Berkeley Castle in 1327. Rumors of murder have persisted over the centuries. Edward’s end, whether by murder or natural causes, was symbolic of the perils of isolation, favoritism, and ineffective leadership in a feudal society that valued—and expected—strength from its monarch.

Edward II’s reign and his subsequent downfall had lasting effects on the English monarchy. His deposition established a dangerous precedent for the nobility’s accountability over the crown, an idea that would echo in English constitutional developments centuries later. His story remains a potent reminder of royal vulnerability in the Plantagenet dynasty, known more for its power and drive.

Edward III:

Warrior King and the Rise of English Identity

Reign as King of England: 1327–1377 Spouse: Philippa of Hainault

Legacy: Initiated the Hundred Years’ War and presided over a cultural golden age. Birthplace: Windsor, England

Edward III, born in 1312, succeeded his father, Edward II, to the throne in 1327. Initially under the regency of his mother, Isabella, and her lover, Roger Mortimer, Edward seized control in 1330 by having Mortimer executed and claiming full power. During his long rule, he restored royal authority, expanded territorial claims, and fostered a strong sense of English national identity by linking it to the chivalric culture of his time.

The decision to press his claim to the French crown in 1337, beginning the Hundred Years’ War, was both audacious and consequential. Asserting a right through his mother, Edward’s campaign was as much about asserting dominance over his continental rivals as it was about lineage. The English victories at Crécy in 1346 and Poitiers in 1356, both won by his son Edward the Black Prince, brought fame to the English crown and fed the chivalric fantasies of the nobility. Chronicler Jean Froissart described Edward as a “model of kingship” revered for his military acumen and courtly virtues.

Domestically, Edward presided over significant governmental evolutions. He confirmed and extended Parliament’s power, particularly the House of Commons’, in taxation and war funding, setting precedents for constitutional monarchy. The Order of the Garter, which he founded in 1348, captured the era’s spirit of chivalry and brotherhood in arms, while the outbreak of the Black Death in the same year devastated the population and had profound long-term economic and social impacts, weakening the monarchy’s influence.

Edward’s final years were less glorious. As he aged, his rule was marred by favoritism towards unpopular advisors and a lack of a clear successor following the death of his heir, the Black Prince, in 1376. Edward III died in 1377, leaving the throne to his ten-year-old grandson, Richard II. Edward’s reign had set the stage for England’s medieval apex and expansionist ambitions. Still, his death left a kingdom with growing problems and no longer capable of the kind of political victories that it had earlier won.

Richard II:

A King of Splendor and Strife

Reign as King of England: 1377–1399 Spouse: Anne of Bohemia, later Isabella of Valois

Legacy: Deposed by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke; his reign marked the decline of Plantagenet unity.

Birthplace: Bordeaux, France

Richard II became king in 1377 at the age of ten, following the death of his grandfather Edward III. As a child king, his early reign was dominated by powerful nobles and regents. In 1381, his rule was challenged during the Peasants’ Revolt, a widespread uprising driven by harsh taxation and social inequality. Richard, only 14 years old at the time, displayed notable resolve in meeting with the rebels and temporarily quelling the rebellion. This act would later win him some admiration for his courage and dignity in the face of crisis.

In his early adulthood, Richard’s rule became more autocratic and aloof. He surrounded himself with a group of loyal courtiers, often distancing himself from his traditional noble advisors and expectations. This bred significant resentment among the aristocracy. His cultivated court, emphasis on royal ceremony, and the promotion of the divine aspect of kingship became increasingly alienating for many subjects and nobles. In 1387, a group of nobles known as the Lords Appellant challenged the king, defeating his supporters in battle and subsequently executing several of his closest allies in 1388, in an event known as the “Merciless Parliament”.

The 1390s were marked by Richard’s vengeance against his previous opponents and a reign of increased severity and autocracy. The king’s confiscation of land and titles from powerful nobles, including his cousin Henry Bolingbroke, sowed the seeds of discontent that would later prove his undoing. In 1399, Richard left England to campaign in Ireland, and Bolingbroke returned to England with an army. Quickly gathering support, Richard was captured, deposed, and imprisoned in 1399, ending his reign and marking the definitive transition to Lancastrian rule under Henry IV.

Richard II died in captivity, under mysterious circumstances, likely murdered in 1400 at Pontefract Castle. While his reign was ultimately a failure, he nonetheless cast a long shadow over the monarchy. A patron of the arts, Richard cultivated a fashionable court and was an early proponent of the divine right of kings. He highlighted both the vulnerabilities of royal authority and some of the latent tensions within the Plantagenet house.

His deposition provided a brutal lesson in the potential pitfalls of political isolation and absolutist rule. Richard set out to create a king above politics and faction, but his inability to deal with the realities of baronial power and aristocratic ambition led to his downfall. His reign signaled the end of an era for Plantagenet rule and the start of another, more troubled one.

Henry IV:

A Crown Claimed, A Kingdom Tested

Reign as King of England: 1399–1413 Spouse: Mary de Bohun, later Joan of Navarre

Legacy: First Lancastrian king; usurped the throne and faced numerous rebellions. Birthplace: Bolingbroke Castle, Lincolnshire

Henry IV’s ascension to the throne was nothing short of revolutionary. In 1399, he unseated his cousin Richard II to become the first king of the House of Lancaster. As his claim to the throne was not based on direct primogeniture, his rule was always somewhat tainted by a lack of the legitimacy afforded to his predecessors. He relied instead on his political acumen and popularity among the nobility to take the crown, ending Richard’s ineffective and unpopular rule, but also setting a dangerous precedent of overthrowing an anointed king, a precedent whose consequences would come back to haunt the Plantagenets decades later.

Rebellion broke out almost immediately after his coronation. The Percys, the powerful family of Henry’s closest ally, rebelled against him, forcing the king to face them in battle at Shrewsbury in 1403. Henry emerged victorious from the battle, but his hold on the throne remained tenuous, with Owain Glyndŵr in Wales and continued plots among the nobility forcing the king to spend much of his reign consolidating his power.

Henry’s claim to the throne also forced him to shore up his legitimacy on a spiritual level. Aided by conservative church leaders, Henry encouraged the persecution of heresy, particularly the Lollard movement, a form of religious reform that threatened the crown and the church. In 1401, the statute De heretico comburendo would be passed to make burning at the stake legal for heretics.

In his later years, Henry began to suffer from recurring bouts of illness, possibly a form of skin disease or epilepsy, which weakened his hold on power and allowed his son and heir, the future Henry V, to take more control of the government and military. Henry IV managed to hold onto the throne until he died in 1413. Still, his reign was largely unremarkable, defined by internal instability and cautious consolidation rather than by any great triumphs or sweeping reforms.

Henry IV’s legacy is in many ways one of pragmatism and sheer endurance. Despite his comparative lack of martial or domestic achievements, he managed to retain the throne in the face of near-constant opposition and did much to ensure that his son would follow him. His reign reflected the changing nature of kingship, making it more dependent on political survival than on divine right.

Henry V:

Warrior King and the Height of Lancastrian Glory

Reign as King of England: 1413–1422 Spouse: Catherine of Valois

Legacy: Hero of Agincourt; nearly united the English and French crowns.

Birthplace: Monmouth, Wales

Henry V became king in 1413 with the firm intention of restoring royal power and renewing England’s war in France. In marked contrast to his father’s embattled reign, Henry radiated strength and unity. He made peace with all his political enemies, including the heirs of those killed or executed in the aftermath of Henry IV’s accession. In speech and action, the new king established a reputation for justice and discipline that won him the support of Parliament and the military elite.

In 1415, Henry V embarked on a hugely ambitious military campaign in France, culminating in the famous Battle of Agincourt. Against overwhelming odds and in the grip of a debilitating illness, his army routed the French in a battle made all the more remarkable by the muddied battlefield and the massed ranks of French cavalry. English longbowmen mowed down enemy knights in one of medieval warfare’s most famous examples of “sharp practice”. Victory in this battle, in which Henry personally killed French knights on the field, established the new king as a warrior-king of near-mythical proportions. Chronicler Thomas Walsingham wrote, “No man ever showed more valour or proved a greater captain in war.”

On the heels of his military triumph, Henry followed up with a diplomatic coup. In 1420, he and King Charles VI of France signed the Treaty of Troyes, in which the French king recognized Henry as his heir and provided his daughter, Catherine of Valois, in marriage. For a moment, it seemed that Henry had achieved what generations of Plantagenet ambition had sought: a dual monarchy that united the English and French crowns. The image of his court, saturated with ideals of chivalry, and his own pious demeanor, cemented the aura of kingship he had cultivated with such rapid success.

Henry’s triumph was to be short-lived. The king died of illness in 1422 while on campaign in France, months before Charles VI’s death. He left the crowns of England and, nominally, France to his nine-month-old son Henry VI, who was unable to hold onto the family’s achievements. The nine years of Henry V’s reign were impressive by any standard. With a combination of martial prowess, political acumen, and personal charisma that has never been bettered, Henry V is one of the most popular kings in English history.

Henry’s victory in France left more than just battlefield success and a dynastic connection to the French crown; it provided the narrative for centuries of English nationalism and kingship. His reign marked the high point of Lancastrian power, and it would resonate in legend, literature, and politics for generations to come. “Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more” – as Shakespeare put it, Henry V was the embodiment of the medieval English warrior-king.

Henry VI:

The Gentle King in an Age of Turmoil

Reign as King of England: 1422–1461, 1470–1471

Spouse: Margaret of Anjou

Legacy: His weak rule and mental illness contributed to the Wars of the Roses. Birthplace: Windsor Castle, England

Henry VI succeeded to the throne in 1422 as an infant. As well as inheriting the English crown, the Treaty of Troyes made Henry the heir to the French throne. Henry was a pious, bookish, and deeply religious man; qualities more befitting of a monk than a medieval monarch. Henry’s long minority was ruled by a series of regents and nobles acting in his name. This allowed many individuals to accrue power, creating the factionalism and tensions that would later emerge in open conflict. Henry’s accession as king met little resistance, but his passive nature left him at the mercy of competing magnates.

England’s position in the Hundred Years’ War rapidly deteriorated during Henry’s reign. Key French territories were lost, including Normandy and Gascony. The deaths of commanders like the Duke of Bedford, as well as the ascension of Joan of Arc, swung the conflict in France’s favor. The loss of French territories, along with high taxes and economic stagnation, led to domestic unrest. One contemporary chronicler noted: “The realm was divided, and the people vexed with heavy burdens.”

Henry married Margaret of Anjou in 1445 as part of a bid for peace. Margaret was a strong-willed queen who became embroiled in government and antagonized the Duke of York. Political unrest devolved into violence, and by 1455, the Wars of the Roses had begun. Henry suffered from periodic mental illness throughout his reign, leaving a power vacuum that competing factions would battle over. Henry’s inability to provide strong leadership proved disastrous, and civil war tore the Plantagenet dynasty apart.

Henry was deposed in 1461 by Edward IV, but returned to the throne briefly in 1470 (the Readeption). However, his second reign was short-lived. He was captured after the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471 and placed under house arrest in the Tower of London. Henry was murdered within days of his son’s death in battle, most likely on the orders of Edward IV. His quiet piety and pitiable end contributed to Henry’s reputation as a saintly figure in later generations.

Henry VI was personally virtuous but a disastrous king. His reign saw Plantagenet England’s once-great overseas empire unravel, as well as the disintegration of internal stability. His peaceful nature was out of step with 15th-century kingship and could not cope with the challenges of his time.

Edward IV:

Restoring Order Through Strength & Strategy

Reign as King of England: 1461–1470, 1471–1483

Spouse: Elizabeth Woodville

Legacy: First Yorkist king; restored order during the Wars of the Roses.

Birthplace: Rouen, France

Edward IV first took the throne of England in 1461, triumphing at the pivotal Battle of Towton. This conflict was one of the largest and bloodiest in English history, with Edward’s forces emerging victorious. Standing over six feet tall, Edward was a charismatic leader, the first king from the House of York in the dynastic Wars of the Roses. He claimed the English crown by the right of conquest, overthrowing the Lancastrian King Henry VI. His military might and strategic marriages secured Yorkist rule and brought stability to the kingdom.

Edward was a competent ruler and commander who, during the 1460s, ushered in a period of relative peace and restored royal power. He was able to balance the kingdom’s finances and promote prosperity at home. However, his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville without consulting his council or the Earl of Warwick caused a significant rift with those nobles. This led to Warwick’s rebellion and a temporary loss of the crown in 1470.

Edward IV regained the throne from Henry VI in 1471 after a period of exile. The king defeated the Lancastrians decisively at the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury, eliminating his rivals. The Lancastrian Prince of Wales was killed, and Henry VI soon died, bringing an end to the male line of the House of Lancaster. Edward’s second reign was more secure, and he took steps to consolidate his power and discourage further insurrection.

The king was a great patron of the arts and is remembered for his extravagant court. His policies encouraged trade and the growth of London as a commercial hub. Edward’s preference for his Woodville relatives over other noble families caused discontent, and his untimely death in 1483 at the age of 40 created a power struggle. His son, Edward V, was never crowned and his uncle Richard usurped the throne, a mystery that is known as the Princes in the Tower.

Edward IV’s legacy lies in his role in centralizing the monarchy, setting the stage for England’s departure from the feudal anarchy that preceded him. Edward was an imposing warrior king who not only defeated his enemies but projected an image of royal splendor and authority that commanded loyalty. He demonstrated political savvy and adaptability, reclaiming and maintaining the crown in a period where allegiances were often fleeting.

Edward V:

The Boy King Who Vanished

Reign as King of England: April–June 1483 Spouse: None

Legacy: One of the “Princes in the Tower”; never crowned.

Birthplace: Westminster, England

Edward V is one of the shortest reigning monarchs in English history – and one of the most mysterious. King Edward V was only 12 years old when he ascended to the throne, following the sudden death of his father, Edward IV, in April 1483. He reigned for only two months and was never officially crowned. Despite his youth, he was not permitted to rule directly, but was instead placed under the protection of his uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who was named Lord Protector. But what happened next would forever tarnish the Plantagenets’ reputation.

Edward was initially lodged in the Tower of London in preparation for his coronation, but was soon joined by his younger brother, Richard, Duke of York. The two boys were seen less and less frequently until they disappeared without a trace. In the meantime, their uncle declared Edward and his siblings illegitimate on the grounds of Edward IV’s precontract of marriage, and took the throne for himself as King Richard III. The legitimacy of his claim is one of the most controversial aspects of the Wars of the Roses.

The fate of Edward V and his brother is one of history’s most enduring mysteries. Many historians believe that the “Princes in the Tower” were murdered, likely on the orders of Richard III, to remove potential rivals for the throne. Others suggest that later pretenders to the throne, such as Perkin Warbeck, may have been the missing princes and therefore survived. But without concrete evidence, their ultimate fate has never been conclusively proven, and their story continues to fascinate historians and the public alike.

While his reign was short and largely symbolic, Edward V’s disappearance had a profound effect on public confidence in the monarchy. It led to increased Yorkist resistance and set the stage for the rise of the Tudors, who used the mystery to demonize Richard III. Edward’s brief and silent reign marked the end of the Plantagenet dynasty and the beginning of a new era in English history.

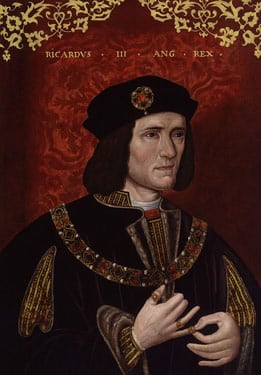

Richard III:

The Last Plantagenet King

Reign as King of England: 1483–1485 Spouse: Anne Neville

Legacy: Last Plantagenet king; defeated at Bosworth Field, ending the Wars of the Roses.

Birthplace: Fotheringhay Castle, England

Richard III’s accession to the throne was as dramatic as it was contentious. In 1483, upon the death of his brother Edward IV, Richard became Lord Protector to his 12-year-old nephew, Edward V. He had his new royal nephew and his siblings declared illegitimate and ascended to the throne within weeks. He proclaimed his takeover lawful, but many remained unconvinced. The enigmatic disappearance of the young Edward V and his brother Richard, known as the “Princes in the Tower,” left an indelible stain on Richard’s reputation.

Richard III enacted several reforms in the short time he was in power. He made the justice system more equitable for the poor and curbed the power of royal officials. He even passed laws that would prevent landowners from exacting unfair revenge against tenants and outlawed the denial of reasonable bail for suspects. These and other reforms show that he did have a sense of justice—when it did not directly affect members of his family.

More than reform, Richard III’s reign was one of political conflict. His usurpation of the throne cost him much of the Yorkist faction and led to revolt. The most significant threat to his reign was Henry Tudor, a distant Lancastrian claimant. The two faced off at Bosworth Field in 1485. Richard fought bravely, and, in Shakespeare’s fictionalized account of his last words, bellowed, “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!” On the battlefield, Richard was killed, and he remains the last English monarch to die in combat.

Richard III’s death ended the Plantagenet dynasty and marked the beginning of the Tudor age. He had been vilified for centuries after his death, primarily through Tudor-biased accounts that accused him of being a cruel tyrant who murdered his nephews. In the last hundred years, modern historians have reassessed his reign, and, while much of his reputation has not been restored, a more objective picture of his leadership has emerged. In 2012, Richard III’s body was found under a parking lot in Leicester and excavated, giving one of England’s most infamous monarchs a fittingly eventful posthumous chapter.

he End of the Plantagenet Dynasty and the Birth of a New Era

The death of Richard III in 1485 at Bosworth was more than just the loss of a king; it was the passing of a dynasty. When Henry Tudor defeated and killed Richard at Bosworth, the last Plantagenet king who could be considered truly Plantagenet had met his end. The crown would pass from York to Tudor, and Henry’s reign would go on to change history forever, all the while painting Plantagenet rule as one of tyranny and insecurity. However, for nearly 300 years, from Henry II to Richard III, the Plantagenets had built and shaped the legal system, the administrative system, and constitutional government that England still followed.

The achievements of the Plantagenet dynasty may have been buried under Tudor propaganda. Still, the kings from Henry II to Richard III were instrumental in shaping England as a political and cultural nation. The Plantagenet kings guided England through a period of change, civil wars, foreign invasions and internal strife, from the legal reformations of Henry II and Henry VI to the battlefield valor of Henry V. The Plantagenet dynasty is the reason English law, architecture and legendary lore is what it is today, and studying the period is the best way to understand the medieval political power structure.