Justice or Injustice? The Lindbergh Kidnapping & Trial of Bruno Hauptmann

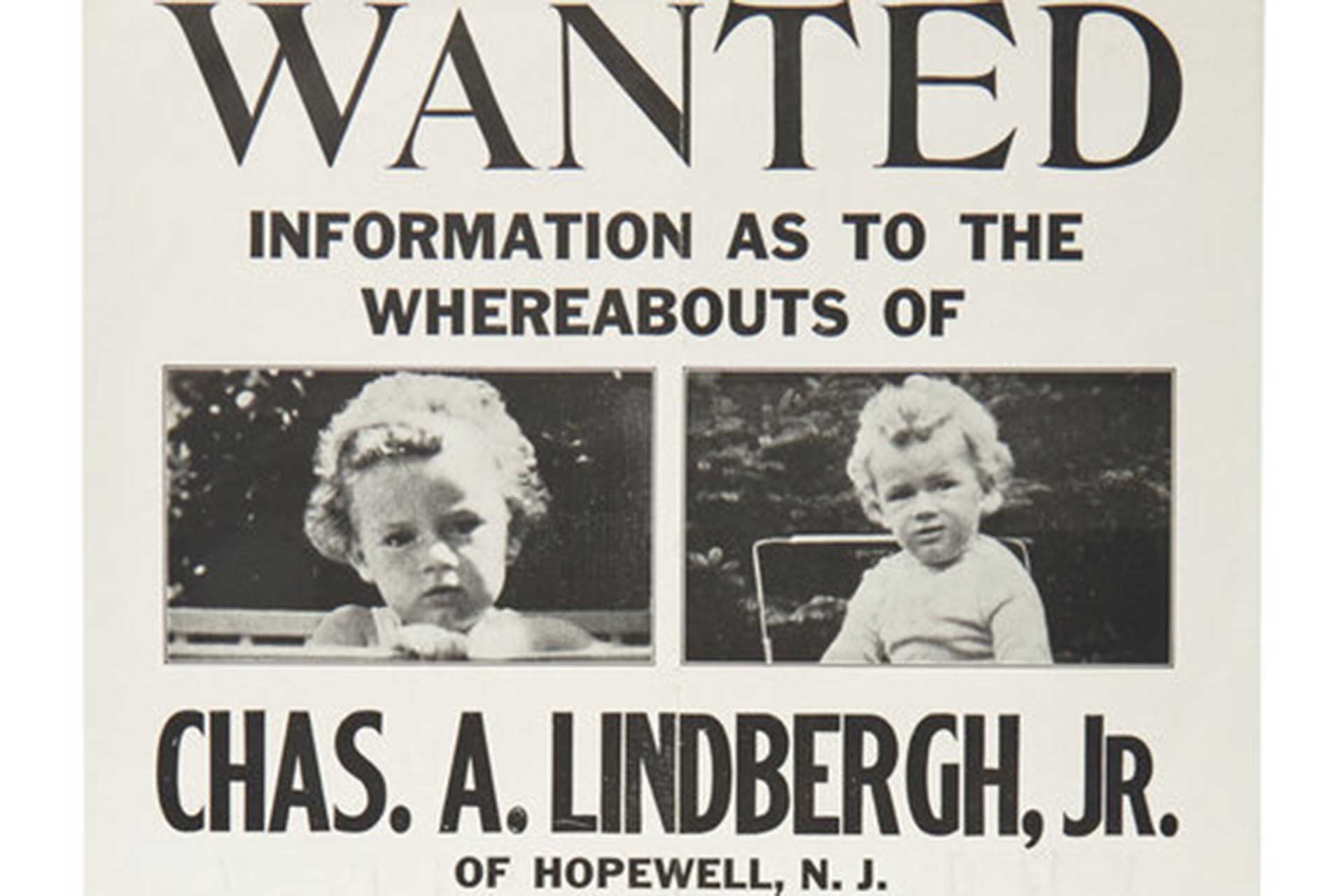

The Lindbergh Kidnapping and the Trial of Bruno Hauptmann is one of the most mysterious and controversial stories in American criminal justice. In March 1932, Charles Lindbergh, aviator, explorer, and the most popular man in the world, endured a personal tragedy when his 20-month-old son was kidnapped from the family’s estate in Hopewell, New Jersey. The crime shocked the nation, and the subsequent investigation captivated the world. For a country still struggling to emerge from the depths of the Great Depression, the story had all the elements of celebrity, horror, and heartbreak wrapped into one. The coverage became so widespread that it soon became known as “The Crime of the Century.”

Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a German immigrant, was arrested and convicted of the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby. His trial in 1935 was a national spectacle, filled with a public clamoring for justice, a questionable crime, and a lack of hard evidence. Today, nearly a century later, the story is as open and shut as ever in the court of public opinion, continuing to raise questions about justice, prejudice, and the power of fame to influence both the truth and the outcome.

Charles Lindbergh: America’s Golden Hero

Before the kidnapping that would forever change his life, Charles Lindbergh was the archetypal American hero. Born in Detroit in 1902 and raised in rural Minnesota, Lindbergh developed an interest in flying from an early age. This fascination would lead him, on May 20, 1927, to fly alone and without stops from New York to Paris in an airplane called The Spirit of St. Louis. The 33½-hour flight made Lindbergh the first person to fly solo nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean, a triumph that instantly catapulted the then 25-year-old air mail pilot to international fame.

Hero’s parades, medals, and world tours followed in rapid succession, and “Lucky Lindy” became a name as familiar in Tokyo as it was in New York City.

Lindbergh’s great achievement was one for the ages, but it was also well timed. His feat occurred at a moment when the world was hungry for heroes. The postwar 1920s were an era of intense aviation activity; Lindbergh’s daring and humility made his character instantly relatable to millions of people, and he became the most recognizable symbol of American resourcefulness and expertise. He quickly became a wealthy man, garnering sponsorships, book deals, and product endorsements. His best-selling memoir, We, would sell hundreds of thousands of copies, while his speaking engagements and aircraft consulting work for the Pan Am airline company would generate vast sums of money.

Lindbergh’s ability to command such impressive sums was remarkable; by the end of the decade, he was a multimillionaire, at a time when few pilots, even star pilots, had ever earned such sums. Despite his newfound wealth, Lindbergh retained his reputation for restraint and modesty.

He married Anne Morrow, the daughter of U.S. Ambassador Dwight Morrow, in 1929, and the two quickly became celebrities in their own right. Known for their elegance and adventurous spirit, the Lindberghs were America’s closest equivalent to royalty. They were widely admired, in part due to their shared interest in flying, which made them an icon of a modern partnership. The couple’s first child, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., was born in 1930.

Dubbed “the world’s most famous baby,” Charles Jr.’s birth was followed by Americans and the international press in the pages of magazines and newspapers. Reporters camped out in front of the family home, and magazines covered everything from the Lindberghs’ travels to Anne’s baking recipes. For many Americans in the dark days of the Great Depression, the Lindberghs represented hope and family.

But this fame had come at the cost of the Lindberghs’ privacy. They purchased a large estate in Hopewell, New Jersey, in the hope of finding some peace away from their public personas and the paparazzi. Still, the family found they could not escape public attention even there. Strangers roamed their land, local reporters tracked their comings and goings, and the family found itself under a microscope. The press attention and public veneration that had once surrounded Lindbergh’s heroics would, in time, slowly unravel the privacy of his domestic life.

By 1932, Charles Lindbergh was no longer just one of the most famous people in the United States. He was one of the wealthiest and most famous men in the world. But for Lindbergh and his family, this wealth, fame, and love would soon become a prison. In March 1932, Lindbergh’s infant son would be kidnapped from his bed in the family’s Hopewell home, a crime that would turn the aviator’s success story into a national tragedy. America’s “golden hero” would find himself at the center of a worldwide controversy that captivated and divided the nation.

The Kidnapping: March 1, 1932

It was late March 1, 1932, in Hopewell, New Jersey, and in the idyllic silence of the night, one of the most notorious crimes in American history was about to take place. At 10 months old, Charles Lindbergh Jr. was abducted from his second-story nursery crib. His parents, Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, were home along with the rest of their household staff. Between 8: 00 and 10:00 p.m., an intruder placed a homemade wooden ladder up against the nursery window and carried the child away into the night. The forced entry into America’s most admired family was a violation of their personal Eden.

Date: 2 May 1932

Betty Gow, the Lindberghs’ Scottish nursemaid, noticed the empty crib when she went to give the baby a bedtime feed at around 10 p.m. She roused Anne, who called for her husband. They searched the house in vain before discovering a handwritten ransom note on the nursery windowsill. It stated that $50,000 in gold certificates was to be exchanged for the child’s safe return. Outside the nursery window, the investigators found footprints in the mud and a chisel. They also found the remains of the ladder that the intruder used to enter the house.

The investigators theorized that the perpetrator had watched the house, selected a night when all the windows were locked and there was no moon, and planned each detail before entering the home.

The kidnappers’ demand of $50,000 was equivalent to almost $1 million today. This was an enormous sum during the Great Depression. The handwritten ransom note was poorly constructed and full of grammatical errors, and it was signed with two overlapping circles. It instructed the Lindberghs not to involve the police, or else they would not see their son alive again.

By the next day, the story had already reached national headlines. Extra editions of the daily newspapers were sold on the streets, and radio bulletins interrupted the regular programming.

The Lindbergh kidnapping marked the first major media frenzy of the modern era. Journalists camped outside the home, and the crowds outside became so large that the state troopers had to restrict access to the area. Police from all over the country were involved in the investigation. The New Jersey State Police cooperated with the U.S. Bureau of Investigation (BOI), private detectives, and even President Herbert Hoover. The nation’s newest golden couple was now the focus of its collective terror.

Hope for a happy reunion turned to despair on May 12, 1932, when a truck driver stumbled upon the skeleton of a young child in the woods, less than five miles from the Lindbergh home. The coroner confirmed that the remains were those of Charles Lindbergh Jr. The child had been dead for weeks, probably killed on the night of the abduction. The disappearance of Charles Jr. had become “The Crime of the Century.”

The Manhunt and Investigation

The search for the kidnapper turned out to be the largest manhunt in U.S. history up to that time. Local police and New Jersey state troopers, backed up by federal agents, began the search. The relatively new, but already vastly more powerful Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) took a hand, in effect coordinating the investigation as it crossed state lines. Charles Lindbergh, with his newfound celebrity, was directly involved in the investigation from the outset. He went door-to-door in the Bronx apartment buildings, offered to pay $5,000 for information and personally appealed to gangsters for help. Even though the case received thousands of tips and had many suspects and false leads, it became colder as the months passed.

Tracking down the ransom money led to a breakthrough. In April 1932, the Lindberghs had paid the $50,000 ransom in marked $100 gold certificates through an intermediary, a man they called “Jafsie.” Jafsie was the alias used by Bronx schoolteacher Dr. John Condon, who volunteered to act as a go-between. Although the money was paid, the baby was not returned. It took two years for the first solid lead to come along. In 1934, with gold certificates being phased out, some of the ransom bills began turning up in New York City and the surrounding areas. Bank tellers and gas station attendants were alerted to be on the lookout for them.

The case took on new life on September 18, 1934, when a Bronx gas station clerk received a $10 gold certificate from a customer and, thinking it might be related to the Lindbergh case, scribbled down the license number. The car was traced to a 35-year-old German immigrant carpenter, Bruno Richard Hauptmann, who lived with his wife and young son. He was placed under surveillance and was arrested shortly after. In his garage police found more than $14,000 of the ransom money in a gas can in the garage of Bruno Hauptmann.

Forensic evidence quickly piled up. Experts testified that the handwriting on the ransom notes was Hauptmann’s. A board found in his attic and tested by state police wood technologist Arthur Koehler, supposedly matched one of the rails from the homemade ladder used by the kidnapper—right down to nail holes and grain pattern. The prosecution would later claim this as hard, physical evidence. Tools found in his workshop were claimed to have been used to make the ladder.

Taken: September 1932

Hauptmann maintained his innocence from the beginning. He said the money had been put in his garage by a business partner, Isidor Fisch. Fisch, he said, had since died in Germany. Hauptmann denied writing the ransom notes or having any involvement in the kidnapping. Nevertheless, he was an easy suspect for a country that was clamoring for a culprit: a poor, foreign-born, first-generation immigrant with a criminal record in Germany. The capture of Bruno Hauptmann brought the two-year-old mystery to an end. It also set the stage for one of the most controversial trials in U.S. history.

The Trial of the Century (1935)

By January 1935, when Bruno Hauptmann’s trial began, the Lindbergh kidnapping had long held the nation’s attention. Flemington, New Jersey, found itself overrun by reporters, spectators, and law enforcement. Tens of thousands of onlookers packed the courthouse and its grounds, while radio broadcasts and newspaper headlines from coast to coast and around the world brought the case to an even wider audience. It was a spectacle unlike anything America had ever seen, part tragedy, part media circus, and entirely a product of the new mass communications age. The press was calling it “The Trial of the Century.”

The prosecution, headed by New Jersey Attorney General David T. Wilentz, weaved a strong circumstantial case against Hauptmann. The evidence included the marked ransom bills found in his garage, witnesses who identified his handwriting as that of the ransom notes, and an expert who connected wood from Hauptmann’s attic to the ladder used to reach the infant’s nursery. The prosecution also brought witnesses who said they’d seen Bruno Hauptmann in Hopewell near the Lindbergh house, as well as witnesses who claimed he had been spending large sums of cash after the kidnapping. Together, these elements formed a damning web of implication and innuendo that the public found compelling.

The defense, led by attorney Edward Reilly, had a much more difficult task of convincing the jury of Bruno Hauptmann’s innocence. Hauptmann, a German immigrant who spoke little English, maintained his innocence, stating that he had nothing to do with the Lindberghs’ tragedy. He noted that the money in his possession had been left with him by an old business acquaintance, Isidor Fisch, before the kidnapping; that Fisch had since returned to Germany and died; and that he, Hauptmann, had no knowledge that the money was from the Lindbergh ransom.

The defense took issue with the prosecution’s handwriting evidence, questioned the validity of the ladder and wood samples, and argued that Bruno Hauptmann was merely a scapegoat because of his background and immigrant status. The problem for the defense was that, unlike the prosecution, they had very little in the way of resources, and they could not effectively counter the prosecution’s scientific witnesses or its emotional appeal to the jury.

The public all but assumed conviction. The abduction and murder of “America’s baby” had shocked the nation and stirred up feelings of outrage and helplessness. Americans, in essence, were seeing Hauptmann’s trial as a way to regain control, to make sure that some measure of justice would be done. Newspapers and radio broadcasters cast Hauptmann as stoic, unemotional, and a foreigner—unlike the affable Lindberghs.

The atmosphere in the courtroom was highly charged, with loud cheers for the prosecution during its presentation. To expect objectivity or impartiality in that kind of environment was unrealistic at best. As one onlooker of the trial later stated, “Bruno Hauptmann was tried not just for a crime, but for the nation’s anger.”

The jury deliberated for six weeks before finding Hauptmann guilty of first-degree murder. The verdict held up against appeals, and on April 3, 1936, Bruno Hauptmann was executed in the electric chair at Trenton State Prison. He refused to confess to the crime, and he repeatedly told onlookers that he was innocent. His final words on the gallows are said to have been, “I am absolutely innocent of the crime for which I am charged.” The trial marked the end of the Lindbergh case’s search for justice—but the questions have lingered.

Public Opinion and the Question of Justice

The kidnapping and murder of Lindbergh’s baby had captured the nation’s attention, and public opinion was very one-sided when the case finally ended in court. There was a high sense of outrage in the public mind. America’s most popular child was brutally taken from his parents, and justice demanded someone be held responsible. Bruno Richard Hauptmann was the ideal suspect in the public eye. He was a German carpenter with a criminal record.

Anti-German sentiment remained strong in the decade following World War I, and the Depression further exacerbated the fear of foreigners. Newspapers repeatedly highlighted Bruno Hauptmann’s immigrant status, dubbing him “the German monster” or “the foreign fiend.” He was a good match for the nation’s racial biases and distrust of immigrants.

The investigation and arrest were anything but thorough or professional. Evidence was mishandled or contaminated, the chain of custody was sloppy, and witnesses’ statements contradicted one another. Several essential witnesses were later accused of perjury or coercion. Handwriting comparison and wood-grain matching were both subjective and in their infancy at the time. Decades later, many questioned whether the so-called “proof” that the ladder was in Hauptmann’s attic could have been fabricated or coincidental and planted to shore up an otherwise weak case. But public outcry drowned out such criticisms.

The Lindberghs’ status also loomed large over the proceedings. Charles and Anne Lindbergh were heroes, not just victims. Their tragedy had become a national cause, and the country demanded justice in their name. For many Americans, bringing Bruno Hauptmann to justice was not just about punishing a criminal. It was about righting the moral balance that had been thrown into disarray by his actions. Objectivity and concern with facts were pushed aside by the emotions of the time. It was difficult to remain dispassionate about the trial’s outcome inside the courtroom.

The media also played a big part in convincing the public of Hauptmann’s guilt. Newspapers followed every detail of the investigation and trial, almost invariably with a sensational headline. Reporters described his emotionless face as evidence of his guilt and his poor English as an attempt to mislead investigators. Newsreels and tabloid articles transformed the trial into a circus, blurring the lines between fact and rumor, leaving many unable to distinguish one from the other. The court of public opinion had long since convicted Hauptmann before the jury had a chance to weigh in.

The question of whether justice was done at the time was raised even then. A handful of journalists and legal scholars publicly voiced their concerns over the handling of the case, raising concerns that prejudice and hysteria had clouded the facts and due process. In 1935, however, such dissenting voices were shouted down by the public clamoring for closure. The nation wanted the case to be over, and Bruno Hauptmann’s conviction provided it, whether he was guilty or not. But the question remains to this day: was justice done, or was the public’s desire for certainty greater than its commitment to truth?

Alternate Theories and Unanswered Questions

It has been almost 100 years since the kidnapping, but many unanswered questions remain. Though Bruno Richard Hauptmann was convicted of the abduction and killing of Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., many historians and legal experts still question the evidence that convicted him. Some suggest that he was framed—or at least that evidence against him was exaggerated. With public and political pressure to solve “The Crime of the Century”, investigators might have bent rules or fabricated evidence. The ladder wood evidence was contested even at trial, and some of the handwriting samples allegedly linking Bruno Hauptmann to the ransom notes might have been coerced or even faked.

The possibility of an inside job is also one of the case’s enduring mysteries. The Lindbergh home was remote and not yet fully furnished, so only a small circle of family, servants, and workmen would have known its layout. The kidnapper was clearly familiar with the household’s routines, from which window to enter to when the house was likely to be quiet. Some of the theories suggest that members of the household staff, workmen, or acquaintances might have given or sold information about the Lindberghs to a criminal. Though no definitive evidence was ever uncovered, the inside-job theory remains haunting.

The physical challenges of the crime also raise some questions about whether Hauptmann acted alone. The ladder used to reach the nursery window was long and heavy, and two people would have found it much easier to manage than one man in the dark with a child in his arms. The distance traveled and the weight of the ransom money later recovered have also made some suspect that an accomplice helped the kidnapper.

Even some of the law enforcement officials at the time admitted, if only quietly, that they didn’t believe Bruno Hauptmann could have managed the entire job by himself. The prosecution narrative was one of a lone wolf, though, which was a much simpler story for the public to accept.

One of the most enduring alternative theories is based on Bruno Hauptmann’s account of the ransom money. He claimed that the large sums of cash discovered in his garage were left for him by a former business partner, Isidor Fisch, who returned to Germany after the kidnapping and died before Hauptmann was arrested. Critics of the case have noted that while this explanation is suspicious, it was never conclusively disproven. If he was telling the truth, it could mean that Bruno Hauptmann was unwittingly in possession of the ransom money without being involved in the kidnapping or the murder.

Finally, among the most unsettling theories to emerge from the Lindbergh kidnapping are those implicating Charles Lindbergh himself. Some researchers have suggested that Lindbergh used his immense public influence to limit FBI jurisdiction and push for a swift resolution—possibly to protect someone or steer suspicion away from the family. Others, taking a darker view, have speculated that Lindbergh may have known more about the abduction than he revealed.

These claims draw partly on Lindbergh’s troubling later associations—his acceptance of Nazi honors, his advocacy of eugenics, and his documented belief in genetic “perfection.” Such ideas have led fringe theorists to propose that the aviator, disturbed by rumored health issues or deformities in his child, may have staged the kidnapping as a cover-up.

Adding fuel to these suspicions are reports from family staff that Lindbergh had an odd habit of removing his baby from the crib as a prank to frighten his wife and the nurse. While historians like Lloyd C. Gardner and most mainstream scholars dismiss the theory of Lindbergh’s direct involvement as unsupported by credible evidence, its persistence underscores the case’s deep ambiguity.

There is no physical or forensic proof connecting Lindbergh to the crime, yet his charisma, contradictions, and control over the investigation keep the speculation alive. As long as unanswered questions remain, the notion of Lindbergh’s shadow over the case continues to fascinate those who view the “Crime of the Century” as something far more complex than a single man’s guilt.

Legacy of the Lindbergh Case

The legacy of the Lindbergh kidnapping has had a lasting impact on American jurisprudence, the media, and the American psyche. In the case’s immediate aftermath, Congress unanimously passed the so-called Lindbergh Law, formally the Federal Kidnapping Act of 1932. This legislation made kidnapping across state lines a federal offense, giving the FBI broader authority. The law fundamentally reformed the investigation of serious crime in the United States. As the Lindbergh case made clear, local and state resources could not match the manpower and prestige that federal agencies would bring to high-profile crime scenes. The Kidnapping Act would become the legal basis for much of the modern federal government’s criminal jurisdiction.

The trial also permanently altered the cultural dynamics of crime, celebrity, and the press. Newspapers and radio competed to feed a nation’s ravenous demand for information. The sensational case was a media circus in every sense. The American public had never been as captivated by a court case, before or since. The media frenzy during Bruno Hauptmann’s trial set the patterns that have come to define American coverage of celebrity trials, from the Manson murders to the O.J. Simpson case. The Lindbergh kidnapping was a watershed moment for the media’s power—and pernicious influence—in shaping public perception before a trial even began.

While doubt about Bruno Hauptmann’s guilt never entirely disappeared, the decades since his execution have brought a constant stream of renewed speculation. Journalists, historians, and legal scholars have re-examined the evidence, with new details unearthed at every turn. Dozens of books, documentaries, and even forensic reenactments have made the case relevant to new generations of Americans. Most of these have cast serious doubt on whether Hauptmann acted alone—or even at all.

In 1981, the New Jersey Supreme Court reviewed a petition to open the case, even acknowledging potential problems with the collection and preservation of evidence, but ultimately chose not to act. To this day, many are convinced the trial more closely reflected the demands of a grieving nation than the standards of fair justice.

Above all, the Lindbergh case stands as a reminder of how elusive justice can be under the glare of public demand. The tension between resolution and truth that has always informed the American criminal justice system was nowhere more clearly on display than in 1930s America. Under pressure from fear, xenophobia, and a collective sense of violation, the country’s most trusted institutions were more capable of succumbing to an outpouring of public emotion than many realized.

A century after the case, the Lindbergh kidnapping remains both an American tragedy and a national symbol. It demonstrated how fame can distort fairness and how the press can transform a courtroom into a national theater of catharsis. But it also strengthened law enforcement agencies and modernized American forensic investigation. The case lives on today—in courtrooms, in museums, and in that lingering, haunting question that Americans have continued to ask, ever since 1936: was justice served, or was it sacrificed?