Seafaring Innovators: How the Phoenicians Connected the Ancient World

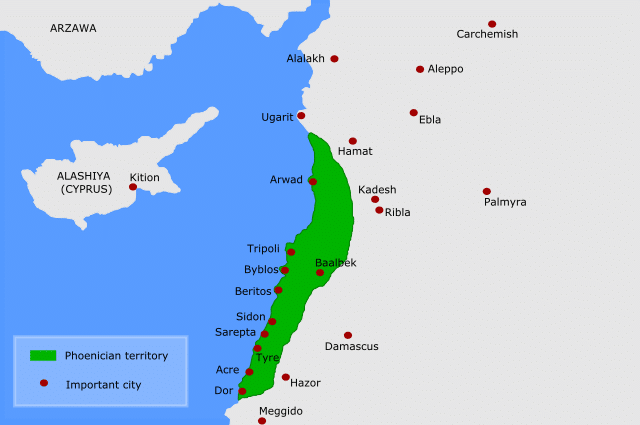

Considered the “cradle of civilization,” the Mediterranean region produced some of history’s most capable seafarers: the Phoenicians. Living in the narrow coastal plains of modern-day Lebanon, the Phoenicians had little access to fertile land or natural resources. As they had no option but to turn to the sea, they found success in seafaring. Sailing out of the ports of Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, they carried on trade expeditions throughout the known world, spreading goods, ideas, and technologies along the way. Herodotus and Strabo were among those to praise their seafaring capabilities, with the former even referring to them as “a nation of merchants” with ships that sailed the length and breadth of the Mediterranean.

The Phoenicians played a pivotal role in shaping and uniting the ancient world by leveraging their innovations in shipbuilding, trade, and navigation to create a more closely knit network of civilizations. The Phoenicians did not build an empire through military conquest, but rather through the establishment of trade routes across the Mediterranean, such as those that connected Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Greece. The Phoenicians were shrewd businessmen and great navigators. As such, they played a pivotal role in early globalization, exporting not just cedar and glass but also the alphabet, which was a key shaper of Western civilization.

The Birth of a Maritime People

The roots of Phoenician civilization can be traced to a narrow strip of territory situated between the azure Mediterranean Sea and the imposing, jagged limestone mountains of Lebanon. Fertile land for cultivation was scarce, yet this land was rich in two assets that would become the cornerstones of the Phoenician economy: the cedar forests and a coastline pocked with natural harbors. With limited potential for agriculture on a large scale, the Phoenician peoples of Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos had little choice but to look to the sea. Geography was both an obstacle and an opportunity, one that would force them to become master shipbuilders, navigators, and traders, who would eventually dominate the ancient Mediterranean.

The beginnings of Phoenician prosperity were straightforward and centered on a few valuable exports. The cedar of Lebanon was in great demand by the ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians for its use in building and its pleasant smell. Records from Egypt indicate cedar deliveries from the “land of the Sidonians” as early as the 3rd millennium BCE. There was also a growing industry of glass and textiles, and above all, the Tyrian purple dye. Extracted from sea snails with great care and effort, the Phoenicians developed a method to create this bright blue pigment, which would eventually become associated with royalty throughout the Mediterranean and bring great wealth to the Phoenicians.

With the development of shipbuilding and navigation skills, the Phoenicians went from trading with their neighbors to becoming long-distance sailors. With open-sea and coastal routes mastered, the Phoenicians reached all across the Aegean and up and down the coast of North Africa. Timber, glass, and metalwork were traded for precious metals and agricultural products, as far away as Egypt and Mesopotamia. Remains of Phoenician amphorae, as well as luxury items, have been discovered on Cyprus, Crete, Sardinia, and Malta, indicating a vast trade network that stretched for thousands of miles. The Mediterranean Sea became a shared marketplace and a place of cultural exchange as Phoenician ships docked at their destination, their hulls packed with new merchandise from other places.

The Phoenicians’ position as intermediaries in these trade routes put them at the center of ancient civilization. Nestled between the great kingdoms of Egypt to the west and Mesopotamia to the east, the Phoenicians became carriers and distributors of art, technology, and religious ideas. Egyptian iconography, combined with Mesopotamian artistic traditions, gave Phoenician art a unique yet cosmopolitan look. The Phoenicians extended their influence across the Aegean and beyond through trade, with lasting effects on the material culture and spiritual beliefs of the regions they reached.

In addition to their mercantile expertise, the Phoenicians also developed a worldview that was adaptable and open to external influences due to their close relations with many other peoples. The flexibility of the Phoenicians, their ability to adapt easily to others, enabled them to succeed where other powers had failed. As larger powers clashed in a struggle for regional hegemony, the Phoenicians were able to form connections across the ancient world, binding it together through trade, craftsmanship, and the ceaseless ebb and flow of the sea. Phoenician identity as a maritime civilization was thus not only economic, but cultural, forged by the Phoenicians’ understanding that their true strength was in connection, not dominance.

The Ships That Changed the Seas

The Phoenicians’ most enduring contribution may have been their ships. Both needs and environment influenced their ingenuity in ship design and production. The coastline and climate necessitated the development of a versatile fleet that could navigate the Mediterranean and its surrounding seas, and their ships served both commercial and military purposes. Ships such as the rounded merchant vessel known as a gaulos and the slender two-tiered warship known as a bireme revolutionized sea travel. These ships formed the foundation of Phoenician maritime trade and played a crucial role in their domination of the Mediterranean for generations.

The gaulos, which was a large, round merchant ship. It had a broad hull, which enabled it to carry a significant load of timber, amphorae, and cloth. It also had a powerful keel, allowing it to navigate the deep waters of the Mediterranean. Its sails were made of woven flax and filled with wind. Steering oars were also used for better navigation.

In contrast, the bireme was a faster and more powerful ship. Two levels of oarsmen propelled it. The prow was also often reinforced with a bronze ram for attack. The bireme was used for raids and warfare. These two types of ships were crucial to Phoenician maritime trade and were used for both commerce and war, serving both commercial and military purposes

Phoenician ships were more technologically advanced than those of other cultures at the time. Their ships were constructed with a curving hull, which cut more easily through waves, and their hulls were reinforced with overlapping wooden planks, which were then sealed with pitch and fiber. These techniques enabled increased durability and buoyancy, allowing the ships to carry heavier cargo and undertake longer voyages. Later, Greek and Roman ships would borrow many of the features of Phoenician ships, including the method of hull construction and specific design elements. A Greek historian stated that the Phoenicians “first taught men to trust themselves to the open sea.”

Excavations have provided additional evidence of the strength of their ships. Shipwrecks found near Israel and Spain revealed that these ships were well-built and featured unique construction methods, including dovetailed joints, notched and pegged planks, and the use of leather for caulking. Some of the amphorae were still sealed with resin and contained wine, which showed that the ship had been prepared for a long journey.

There are also some depictions of ships on reliefs found at Byblos and Carthage. These carvings depict strong vessels with a high prow and various decorative elements on the hull and sails. The sails of the ships were striped, and the hulls had different patterns on them. These carvings are rare evidence of what some of their ships may have looked like.

Phoenician ships were among the finest in the Mediterranean during their time, boasting exceptional durability, speed, and maneuverability that made them the preferred choice for long journeys. The ships and the ability to build them became a source of both wealth and mobility for Phoenicians, which was an essential aspect of their culture and trade network. Every successful voyage was another testament to their reputation as the masters of the sea, and their ships were the tools that changed the face of civilization around them.

Navigating the Unknown

The strength of their trade and their dominance of the Mediterranean were dependent not on the vessels alone, but rather on the sailors themselves. The Phoenicians were renowned for their superior navigation skills, particularly in the open seas. Navigation techniques were available to the ancients long before the development of such navigational tools as the compass.

They observed the position of the stars, tide variations, and the appearance of coastlines in relation to direction. Sailors at night used the fixed point of the North Star, the culmination of which sailors later referred to as the “Phoenician Star” due to their navigational acumen. In daylight, they observed the appearance of distant coastlines and headlands, changes in water color, and the flight of seabirds to indicate proximity to shore. They became familiar with wind directions in relation to seasonal currents.

This knowledge made them more adventurous and more willing to try voyages over longer distances. The Phoenicians are said by some sources to have ventured into the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar (known to the ancients as the Pillars of Hercules). Their ships traded with coastal tribes and cultures of the Iberian and North African peninsulas, while founding colonies and trading stations that would extend their reach even further.

The Greek historian Herodotus wrote of a Phoenician voyage commissioned by the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II around 600 BCE, which circumnavigated Africa. The sailors, he says, after three years returned claiming to have seen the sun to the right of them while sailing westward – a statement that makes the possibility of their having done so very likely.

The Phoenicians became masters of these open seas because they had charts memorized from the knowledge gained and orally transmitted by previous generations of Phoenician seafarers. There is some evidence that the Phoenicians also used basic instruments to aid them. For example, sounding weights were used to measure the depth of the water, and sea routes were recorded using symbols.

Added to the intimate, experiential knowledge that the Phoenicians were known to have possessed, these would give them a command of the sea that many others would have feared to approach. Their skill in navigating such areas was greatly desired by other kings and traders, further expanding their geographical knowledge of the sea. A reputation as a seafarer without fear made it so that wherever Phoenicians sailed, their renown went before them.

It was by navigating the unknown that the Phoenicians were able to open the seas as a channel of trade and exchange. Their ships had linked distant lands and cultures, establishing the first long-distance, sustained maritime trade routes of the ancient world. The Phoenicians opened up more than trade with their navigation skills, but rather the first seaborne exploration of any kind. By subjugating the elements and by daring to explore, they changed not only the boundaries of ancient maps but also the very possibilities of human life.

Building a Trade Empire

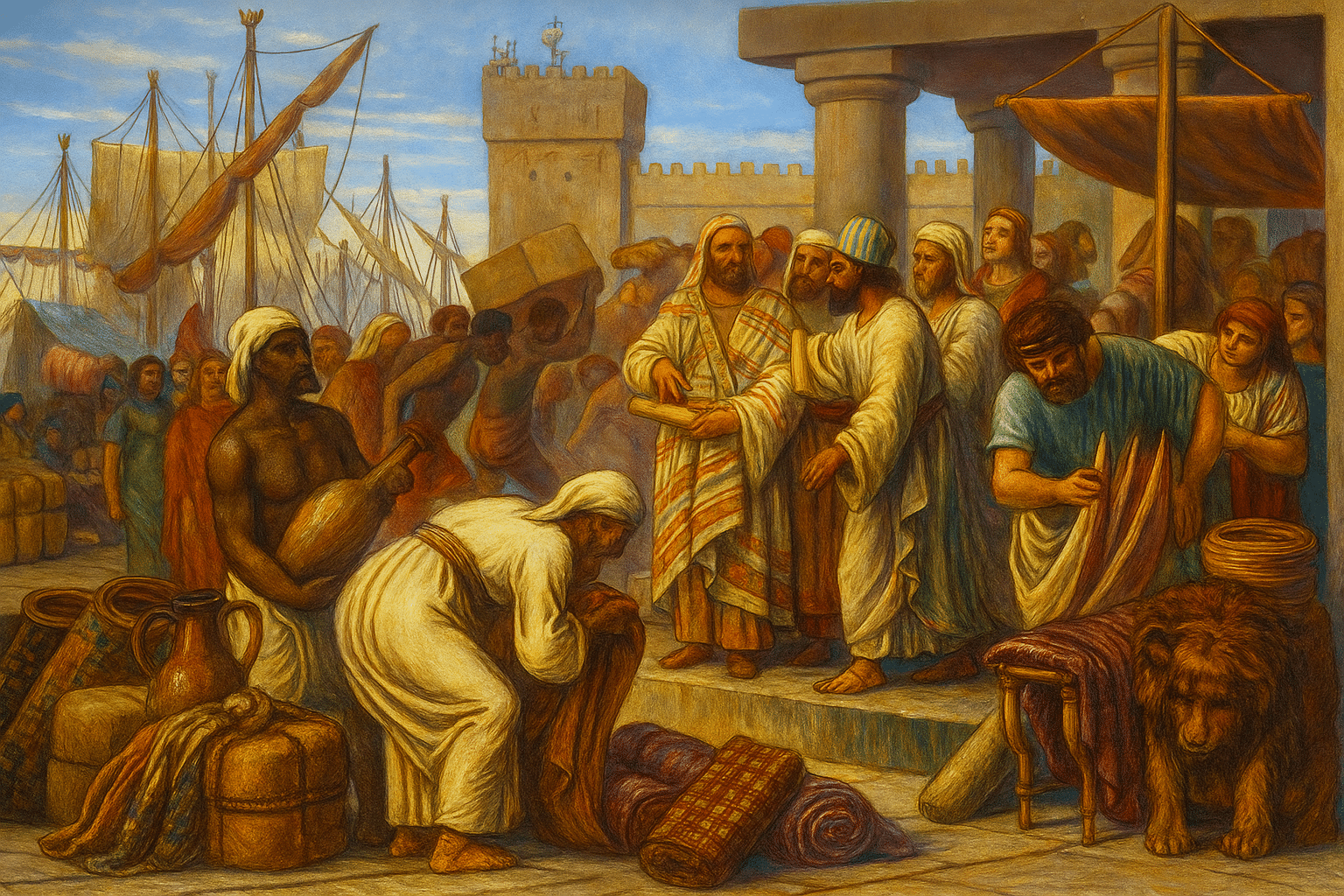

Trade was a central aspect of Phoenician civilization. As a people without significant natural resources or a large agricultural base, they had little choice but to seek their wealth and power from the sea. Ships loaded with timber, textiles, glassware, and carved ivory ventured forth from their cities of Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, establishing trade routes that spanned the Mediterranean. These Phoenician vessels returned laden with goods and raw materials that were either scarce or unavailable in their homeland.

The Phoenicians were renowned for their fine cedar wood, which was highly sought after for construction and shipbuilding. This wood was used in Egypt by the pharaohs for ships and temples. They also traded vibrant textiles dyed with Tyrian purple, exquisite glassware, and crafted ivory goods. These luxury items were highly prized in foreign courts, ensuring that Phoenician traders were always welcome in places where wealth and power were found.

The Phoenicians imported raw materials and resources that their land could not provide. They would travel to Iberia, Britain, and North Africa to import copper and silver, as well as tin and gold, which they would then trade for manufactured goods. From Egypt, they imported grain, papyrus, and precious stones. Arabian traders supplied them with incense and spices. This exchange of materials created a web of commerce that can be seen as a precursor to the modern global economy, linking the disparate resources of the ancient world. Phoenician ships carried more than just products; they were ambassadors of culture, language, and technology, facilitating an exchange of ideas between civilizations.

Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos were the Phoenician port cities, serving as the economic and political centers of Phoenicia. These cities were fiercely independent but maintained cooperative trade networks. Each had its own speciality—Byblos was known for its papyrus trade in ancient times, Sidon was a center of glass production, and Tyre was the leading political and commercial power. Egyptian and Assyrian records refer to Phoenician merchants as indispensable middlemen who could provide goods rare or impossible for one civilization to acquire alone.

To protect their trade routes and facilitate long-distance trade, the Phoenicians established colonies along the coasts they frequented. The most famous of these was Carthage, which grew from a Phoenician colony in North Africa into a major power in its own right, eventually rivaling Rome. Other colonies, such as Gades (now Cádiz in Spain) and Lixus in Morocco, served as logistical bases and trading depots. These colonies provided a steady supply of materials such as silver, salt, and fish products, while also offering a safe harbor for ships on long voyages.

The network of ports, colonies, and trade relationships that the Phoenicians maintained made them the preeminent commercial power in the Mediterranean. Their ships connected the economies and cultures of the ancient world in a way no other civilization had managed. Through trade, they created

Cultural Carriers and Innovators

In addition to material goods, the Phoenicians also facilitated the exchange of ideas and cultural practices. The merchant cities of the Phoenician coast were cultural melting pots, drawing from the traditions of the many lands with which they traded. Elements of Eastern and Western art, symbolism, and mythology became interwoven in the decorative styles and religious practices found along the coast. Craftsmen in Phoenician cities created luxury goods, such as ivories, jewelry, and glassware, in styles that combined Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Aegean influences. These goods were highly prized and traded throughout the Mediterranean, serving as ambassadors of Phoenician art and culture.

The Phoenicians were also influential in the spread of religious practices and beliefs. The primary deities of the Phoenician pantheon, including Baal and Astarte, were adopted by the cultures they traded with, often merging with local gods and goddesses. The religious architecture and artifacts found in Phoenician-influenced sites, such as the temples in Cyprus, Carthage, and Sicily, attest to the spread of their religious practices. This shared religious culture helped to establish a common identity and understanding between different trading partners, smoothing the path for commerce and diplomacy.

In a world where politics and religion were deeply intertwined, this cross-pollination of belief systems served to solidify alliances and ensure peaceful relations.

The Phoenicians’ most significant contribution to the cultural fabric of the Mediterranean may well be their invention of their alphabet. This writing system, refined for trade, had a profound impact on the cultures it touched. The Phoenician alphabet was derived from earlier Canaanite scripts but was much simpler, using just twenty-two symbols to represent sounds rather than words or ideas. This simplicity made it easier to learn and more versatile, enabling the recording of transactions and treaties with unprecedented efficiency. The Phoenician alphabet was readily adaptable to different languages and could be inscribed on a variety of materials, including clay, papyrus, and parchment.

The use of the Phoenician alphabet spread along with their trade networks. The Greeks adopted it around the 8th century BCE, making several modifications, including the addition of vowels. The alphabet then passed to the Etruscans and, eventually, to the Romans, whose Latin alphabet is the ancestor of most Western scripts. Through these channels, a writing system created to keep trade records became the foundation of literature, law, and education across continents.

The Phoenicians, through their extensive trade, served as a cultural bridge between the East and the West, disseminating ideas and practices that would have a lasting impact on the ancient world. Their legacy is not one of empire or monumental architecture but of the intangible threads of culture they wove between distant peoples. In their ships and marketplaces, art was exchanged that would inspire new aesthetic movements, religious beliefs were shared that fostered understanding and connection, and a written language was disseminated that gave voice to the thoughts and stories of generations to come.

Diplomats of the Sea

In a world where might often made right, the Phoenicians were experts in the more delicate dance of diplomacy. Thriving between empires as fierce as the Egyptians, Assyrians, Hittites, and later Babylonians, they carved out a niche as mediators in a volatile geopolitical landscape. Neutrality was a necessity for Phoenician cities scattered along trade routes that could quickly turn into battlefields. In this environment, where the borders of rival powers shifted like desert sands, a policy of appeasement was crucial for survival.

Egyptian texts from the New Kingdom era refer to Phoenician delegates bearing tribute at Thebes, accompanied by ships laden with cedar wood, gold, and skilled artisans. Yet these gifts were not simply one-way offerings of submission; they were part of a complex exchange. The Phoenicians traded with Egypt during both times of war and peace. They may have paid tribute when circumstances demanded it, but they never allowed themselves to become vassals; instead, they skillfully played larger powers against each other while maintaining their autonomy intact.

Ashurbanipal’s Assyrian annals of the 9th and 8th centuries BCE chronicle “the kings of Tyre and Sidon” presenting gifts and emissaries at Nineveh. However, these tributes were not always an act of deference but a diplomatic investment to preserve trade routes and stave off invasion. Building influence in several spheres at once kept the Phoenicians open to inland markets and protected by the sea. Phoenician vessels would winter in Egyptian ports one year and the harbors of Assyria the next, as they became known more for their reliability than their entanglements in politics.

Marriages between Phoenician and foreign royalty also helped bolster economic and cultural connections. Diplomatic ties, often bound by family alliances, extended the influence of Phoenician city-states far beyond their own shores. The close friendship between King Hiram of Tyre and King Solomon of Israel, recorded in biblical and classical sources, is one of the most famous examples of this type of relationship. The construction of the Temple of Jerusalem utilized Phoenician cedar, gold, and skilled craftsmanship, as both kings benefited from the exchange of goods and services.

The Phoenicians negotiated treaties and trade agreements, as well as formed personal friendships, across the ancient world. This spirit of neutrality made them welcome guests in every port and gave them the status of sea-bound diplomats and peacemakers. The Phoenicians demonstrated that navigating not only the Mediterranean but the turbulent politics of the age required the same precision, resilience, and steady hand as steering through its waves. Their legacy is built not only on their maritime and mercantile achievements but also on their relationships as genuine and skilled diplomats.

Decline and Legacy

Ultimately, the influence of the Phoenician city-states was overshadowed by the expansionist ambitions of the surrounding empires. As early as the 9th century BCE, Assyria had begun to exact tribute from Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, subsuming them into its expanding imperial sphere of influence. While the cities were allowed a degree of autonomy, they were increasingly subject to the demands of greater powers.

This was followed by the Babylonians, who besieged Tyre in the 6th century BCE, putting an end to its independence. The absorption of the area by the Persians under Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BCE would render the Phoenician ports a valuable asset for their new overlords. Despite being under the thumb of regional powers, the innovations and maritime traditions of the Phoenicians continued to spread from port to port.

Under Persian rule, Phoenician sailors would go on to have a major influence on Mediterranean politics. Building and crewing ships for the Persian navy, they were a crucial force in the imperial projection of power and control over coastal cities. Their skills in navigation and shipbuilding were unmatched by the Persian sailors, who were often put in charge of Phoenician ships and crews. Herodotus makes particular note of how much the Persians came to depend on “Phoenician ships and sailors,” a testament to how even their conquerors could appreciate the value of their maritime tradition. Despite being subject to the whims of greater powers, the innovations of the Phoenicians were not lost; instead, they continued to inform their rule.

The most famous city to emerge from the Phoenician diaspora was, without a doubt, Carthage. Fabled for its immense size and wealth, the city was founded by settlers from Tyre around the 9th century BCE on the North African coast. Sharing the same culture and traditions as its parent cities, Carthage built upon the skills and innovations of the Phoenicians, making them the backbone of its own trading network. By controlling the shipping lanes between Spain and Sicily, the city was able to build a commercial and military empire unrivaled in its reach. Carthage is remembered most for its later conflicts with the Romans, but it also served as a powerful link between the Phoenician past and the classical future.

Archaeological remains also provide insight into the continued influence of Phoenician expansion across the Mediterranean. Phoenician language inscriptions have been found across the ancient world, from Malta and Sardinia to Morocco. Ancient glasswork, carved ivories, and the remains of temples and tombs all show an exchange of styles that would shape artistic and architectural traditions in the region for many years. It was even possible to find traces of Phoenician loanwords in the Punic of Carthage, as well as early Semitic dialects.

The influence of the Phoenicians would continue to be seen across the Mediterranean, long after their political influence had waned. In every port city they reached, and in every language written in their alphabet, their legacy lives on. The Phoenicians may no longer possess the same power and influence they once had in the Mediterranean, but their innovations endure to this day. Their impact on the Western world is indisputable, a lasting connection between the ancient past and the present. Their story is not one of empires built in conquest, but of how the art of the sea can shape the tides of history.

The World Connected by the Phoenicians

Our Phoenician predecessors may never have been an empire in the sense of a contiguous, vast territorial stretch. Still, their colonies and trading outposts cover a greater span of the known world than most any other ancient nation. Working in trade, diplomacy, and ship navigation as one of the world’s most intrepid and globally connected cultures, the Phoenicians sowed the seeds of a connected world.

Traveling from Tyre to Sidon and Carthage to Cádiz, the Phoenicians navigated the sea, establishing one of the greatest maritime trade networks in human history. Phoenician ships connected the Mediterranean peoples of Egypt to the Greeks and Minoans, the Levant to Mesopotamia, Iberia, and Europe, and the coastal Near East to North Africa.

The Phoenicians left behind a lasting legacy that continues to influence modern language, culture, and commerce, from the architectural design of their ships and sea travel to their lasting influence on modern Greek, Latin, and Western alphabets.

The Phoenicians also introduced certain economic principles, such as a class division of labor and their own code of law, that had a profound influence on early human civilizations. The cultural exchange that the Phoenicians established between all of these various nations also brought a unique shared opportunity with it.