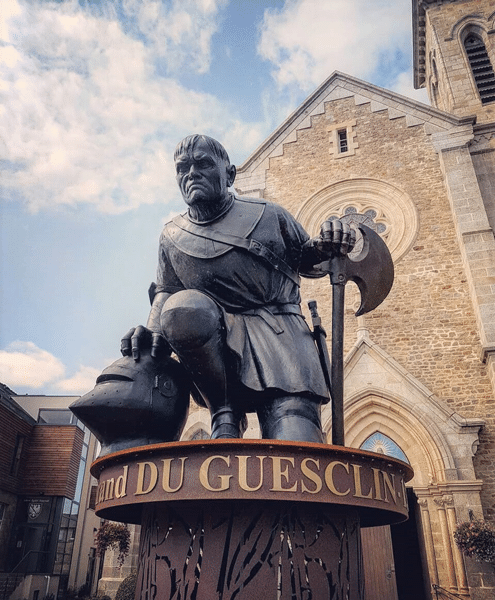

From Soldier to Legend: The Legacy of Bertrand Du Guesclin

The Hundred Years’ War saw many great soldiers and commanders, but very few have received the same recognition and mythical status as Bertrand du Guesclin. A contemporary chronicler described him as rough and coarse, obstinate and quarrelsome – a far cry from the elegant, courtly ideal of the medieval knight. His origins, as the illegitimate son of a Breton noble family, were comparatively humble.

Nevertheless, from these unpromising beginnings would arise one of the most resourceful and determined leaders of the Hundred Years’ War. By force of will and a capacity for hard fighting that belied his disheveled appearance, du Guesclin would rise from his obscurity and leave an indelible mark on the war. By putting his talents in the service of the French crown, the dauntless soldier made a career in the Breton War of Succession, proving his mettle in a series of conflicts that soon caught the attention of the French king.

His reputation would grow through his adoption of an unorthodox, decidedly anti-chivalric style of warfare. His ascent from disdained child to Constable of France embodied a larger national resurgence in the fortunes of war. Chroniclers like Froissart remarked upon his longevity, capacity for survival, and tactical skill. The latter would later write of du Guesclin, a “man… whom no man was more feared or more valued in the kingdom.” This article will explore how Bertrand du Guesclin became one of the most renowned and effective military leaders of medieval Europe.

Bertrand Du Guesclin’s Early Life in Brittany

Bertrand du Guesclin was born around 1320 in the wooded region of Brocéliande, associated with the legends of Merlin and the court of King Arthur. His family was a petty noble family – gentlemen of the countryside, respected in their local community, but with little wealth and no great power or influence in the national arena. As such, he did not have the courtly upbringing typical of young noblemen of the time. On the contrary, medieval chroniclers described him as rough in appearance, a stocky man, who was coarse and unruly.

Later in the century, Jean Froissart, a famous French chronicler, even stated that he was “the ugliest child ever seen”. As such, he was the furthest from the ideals of the knightly nobility in most respects. But it was these very traits that would shape the man he would become.

Bertrand du Guesclin was a strong and determined child. Rather than being raised to be a courtly man of refinement and poetry, he preferred to show his mettle in wrestling matches and martial contests. Chroniclers of his life have described him as the strongest boy in his village, able to best older boys at wrestling, pick up weapons, and use them with ease, and showing a fierce tenacity uncommon in a child his age.

His parents are said to have attempted to curb his rowdy behavior and to instill in him more conventional norms of noble conduct, but it is said that all their efforts were for naught. Clearly a child of war, his untamed aggression gave him the instincts and skills to take him to the battlefield.

These wild and brutish qualities of his youth began to set his legend in local Breton folklore. Some legends describe how he would pick fights with knights who had the temerity to insult him, only to defeat and earn their respect. Other tales tell of a young Bertrand, determined to overcome the physical weakness of his frame, training alone in the forest and testing his might against all and sundry. Whether true or not, these stories (part history, part folklore) give a sense of how early the foundations of his legend were laid.

It would be a mistake to think that, despite his unruly and coarse behavior, there were no signs of the virtues that he would become famous for as a leader and tactician, even in his youth. He was strong, resilient, and fiercely loyal, with an instinctive understanding of people and situations. He seemed to grasp at a young age that he was not the sort of man to be admired for his looks or his charm.

As such, he had the wit to know that he had to outdo his more privileged peers in other ways. He would develop a sense of his own worth and self that would make him confident enough to challenge those who were more socially and politically advantaged than himself. As much as any other factor, this helped to shape the man and the warrior he would become.

Brittany also played a role in forming his character. The region was renowned for its fierce independence, its rugged terrain, and the internecine conflict of its numerous rival factions. These qualities imbued du Guesclin with a unique understanding and approach to war, even in his youth. Whether these tales of his youth are based in fact or in embellished folklore, all seem to agree on one thing. Bertrand du Guesclin was a child who defied expectations and would choose the road of the warrior long before he first donned armor.

First Steps as a Soldier

Bertrand du Guesclin’s first military exploits occurred during the Breton War of Succession, a dynastic conflict that took place between 1341 and 1364. The two opposing claimants to the dukedom of Brittany belonged to the rival Houses of Montfort and Blois, both of which enjoyed the support of England and France, respectively.

As a supporter of the House of Blois, du Guesclin found himself on the French side in a struggle that served to intensify the wider war with England. For the young Bertrand, the war presented an opportunity to make his mark. In particular, he had the opportunity to utilize the skills that came naturally to him. His first campaigns revealed an individual both more ferocious and less refined than his more experienced contemporaries.

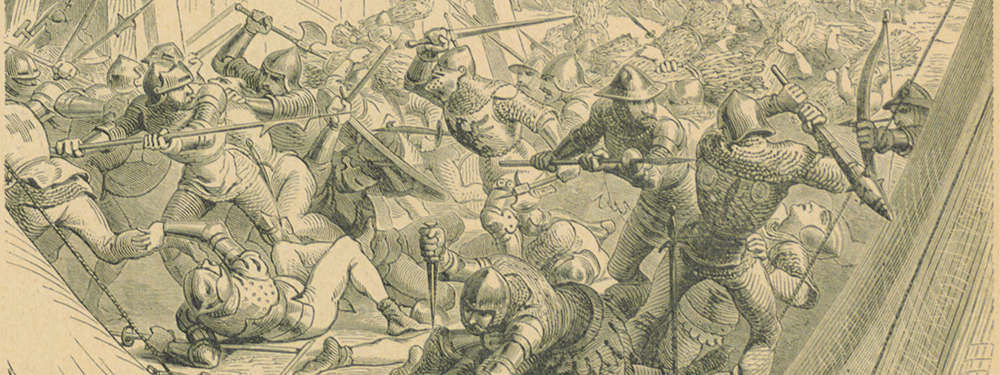

Du Guesclin’s early years of service in the Breton conflict demonstrated a willingness to fight hard, albeit without the elegance of the more polished knights. On multiple occasions, he displayed a taste for ambush, surprise attacks at night, and lightning raids that caught his opponents off guard. Such tactics were considered unconventional, even cowardly, during a period when high value was still placed on set-piece battles and chivalric ideals. By employing them, however, du Guesclin could secure victories despite facing superior or better-equipped foes. His practical approach to combat often earned the ire of his enemies but won the respect of commanders who appreciated results over rigid adherence to codes of conduct.

One early story, for example, recounts how du Guesclin assisted in the defense of Rennes by utilizing his skills to establish a successful system of urban fortifications. He was said to have demonstrated a natural understanding of the art of defense, leading small raiding parties, cutting supply lines, and forcing the enemy to fight constantly in the streets. The result was a prolonged siege, with the city’s defenses maintained until a relief force could be organized. His actions also revealed a certain strategic sense in an otherwise untested warrior.

In the following years, his growing reputation as a force to be reckoned with spread among both his French allies and his Breton compatriots. Du Guesclin’s loyalty to the Blois cause remained steadfast, despite the war’s vicissitudes and the shifting alliances that characterized the conflict in Brittany. He was sent on increasingly important missions, often to those areas that had become particularly unstable or prone to violence. English-backed troops were forced to be on constant guard against his lightning raids, which showed an increasing level of competence and professionalism.

By the mid-1350s, Bertrand du Guesclin was no longer viewed as a loose cannon or a hothead but as a developing talent who could turn the tide of a campaign if properly used. His skill at adapting to circumstances and understanding the terrain and variables of battle, along with his capacity to inspire his men, made him a valuable asset in a war in which France was already short of competent soldiers and leaders. These were his first steps toward a long career, but they were enough to make him stand out and project him from the relative obscurity of regional conflict into the spotlight.

Bertrand du Guesclin – Black Dog of Brittany – Unisex Heavy Cotton Tee

Rise During the Hundred Years’ War

The Hundred Years’ War between France and England would also propel Bertrand du Guesclin into the ranks of the most influential military leaders. Brittany’s endemic factionalism had left both of its main parties feeling particularly isolated and threatened. As a result, many Bretons would choose at various points to side with one or the other of these larger kingdoms.

Du Guesclin was notable in this respect for his steadfast loyalty to the French crown. He made himself worthwhile as a messenger and military adviser. In these roles, he built close relationships with several royal officials. As a relatively unknown commoner from a strategically important border region, he was also helpful as a loyal soldier with few political or personal axes to grind.

Du Guesclin’s service to Charles V marked the beginning of this period of transformation. While he had demonstrated battlefield ability, he was also politically astute. He was well aware that France would need to strike with all of its remaining power and that the nobility, regional commanders, and royal functionaries would need to coordinate their efforts if this was to work.

The result was that du Guesclin became an increasingly trusted adviser to Charles V as well as a personal favorite. Chroniclers reported that the king greatly appreciated the man’s honesty and discipline, famously referring to him as “one whose loyalty cannot be bought nor shaken”. This was a significant advantage in the conflicts of the period, laying the groundwork for the next stage of his career.

In the meantime, du Guesclin continued to demonstrate battlefield effectiveness. His capture of the town of Mantes, for example, displayed both his ability to lead an assault and to conduct a siege. His victory at Pontvallain in 1370 helped to make up for French losses elsewhere, routing English forces before they could regroup. These battles were not pitched melees but instead closely coordinated affairs in which he made intelligent use of small, mobile units. He was able to exploit the gaps and create openings that more traditional commanders of the time could not.

Du Guesclin’s status as a captive furthered his reputation. He was captured several times during this war, and the English were quick to understand his value. His ransoms were correspondingly high and paid in whole or in part by the French crown. On at least one occasion, his enemies even assisted in his ransom. This only served to enhance his reputation, as the knights and nobles on both sides respected his bravery and his ability to avoid unnecessary aggression. Chroniclers described him as courteous to both his captors and his prisoners.

Victories on the battlefield and increasing influence at court both established Bertrand du Guesclin as a leader in the ongoing Hundred Years’ War. He had demonstrated through his actions and example that a combination of strength and careful strategy would be necessary to compensate for the shocking defeats of the previous generation. By the time he was elevated by Charles V to positions of absolute power and responsibility, he was no longer merely a useful commander—he was an emblem of French hope in a war that had previously seemed unwinnable.

Strategic Mastery: The Art of Winning

Bertrand du Guesclin had no time for the bombast of chivalric war. To the dismay of high-born knights who had gathered to see him fight in his youth, the first battles he won were small affairs of attrition, ambush, or siege. He did not seek the panache of grand cavalry charges or large-scale infantry attacks in the open field.

On the contrary, he recognized early on that pitched battles on the open field were, in most cases, English victories in waiting: such battles were arenas in which English longbowmen could mow down mounted soldiers at range, before they could even effectively close the gap. His approach was realistic and rare: he focused on results rather than reputation. This pragmatism quickly became his strategic signature.

A flexible commander, du Guesclin adapted to circumstances, using his relatively small but quick and versatile companies of men in a variety of ways, based on the terrain and the type of war at hand. In hilly country, he made lightning raids and got away before English reinforcements could arrive; in fortified lands, he severed supply lines and forced enemy garrisons to surrender or starve through slow attrition. Chroniclers marveled at his ability to “win without risking all” (without leaving any of his forces behind), and his soldiers respected him for it: he fought courageously, but never heedlessly, and demanded no more of his men than he was willing to do himself.

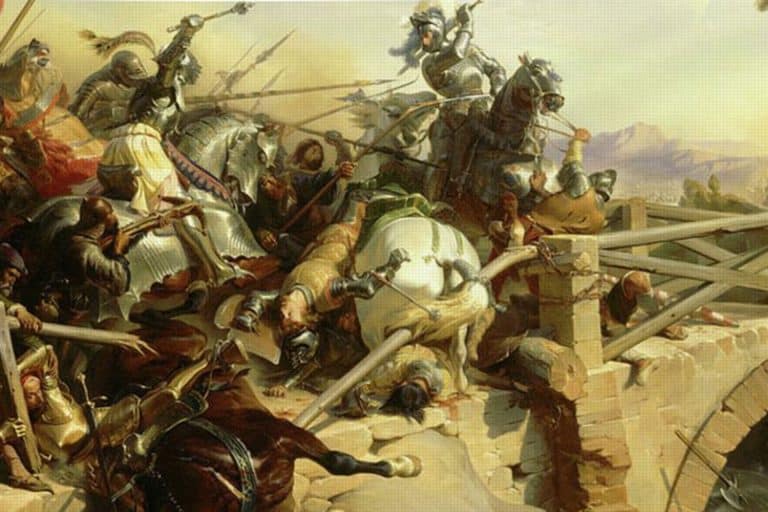

His strategies starkly contrasted with those of the English commanders of the time. English armies in the 14th century were built around longbowmen and their ability to rain deadly missiles on any force that was foolish enough to approach them in the wrong order. At Crécy and Poitiers, the English had annihilated the armies of the French crown in just such a way, goading their enemies into futile direct attacks.

Du Guesclin was keenly aware of the disasters at Crécy and Poitiers and avoided at all costs the same mistakes the previous kings of France had made. He rarely, if ever, let his men attack English longbow formations in the open, and preferred to maneuver the English into a position where their longbowmen would be neutralized.

The stark contrast in approaches was to become the central theme of du Guesclin’s campaign. While the English commanders (particularly their longbowmen) remained confident that war was decided on the battlefield alone, Bertrand du Guesclin made that battlefield increasingly impossible to come by. He attacked unfortified outposts and small encampments in isolated areas, intercepted supply convoys, and invested key towns that the English needed to maintain control of territory but lacked the forces to defend. By avoiding large set-piece battles that had cost France so dearly in the 1340s and 1350s, du Guesclin slowly began to turn back English expansion without risking the security of his own forces.

His campaigns sapped England of its former military dominance. If the English troops were forced to fight on terms they did not control, they were also weakened by constant skirmishing, they faced supply shortages, and they were exhausted and frustrated by du Guesclin’s apparent ability to appear and disappear as he pleased. Du Guesclin’s strategy, on the other hand, allowed French forces to regroup and regain confidence after years of humiliation. The constable fought not for glory but for victory, and his strategy of patience and precision proved that intelligent leadership could overcome even the most formidable opponents.

Bertrand du Guesclin’s approach would prove pivotal in the years to come of the Hundred Years’ War. He was as important for knowing when not to fight as he was for learning how to win. Through discipline, imagination, and a firm determination not to be constrained by chivalric trappings, he revolutionized French military doctrine and demonstrated that the conflict would be decided not by spectacle but by strategy.

Campaigns That Changed the War

Du Guesclin’s campaigns as constable are generally seen as a turning point in the Hundred Years’ War. After a series of defeats and loss of territory in northern and central France, the careful, calculating constable was able to retake many of these places. In Normandy, he sought to reduce the English hold on the fortified towns that had been a key focus of the conflict. Sieges of Mantes, Meulan, and other vital towns began to close the net around English positions on the Seine River. His presence forced them onto the defensive and cut off their supply lines, preventing the English from launching any significant offensive operations.

In Brittany, Bertrand du Guesclin’s knowledge of the region and his personal reputation allowed him to find allies among a people whose loyalties were often quite divided. He could frequently count on local support for his campaigns in western France, which typically followed a similar pattern: avoiding pitched battles, besieging enemy garrisons, and recapturing the land one town at a time. Chronicles of the period frequently remark “that town after town returned to the king’s peace”, speaking to the way that his attritional approach wore down English gains of the previous decades. By the mid-1370s, much of the land France had lost after Crécy and Poitiers had been recovered.

Du Guesclin’s participation in the Castilian civil war is one of the more remarkable periods of his career. In the early 1360s, France had thrown its weight behind Henry of Trastámara’s attempts to unseat his own half-brother, King Peter of Castile. Bertrand du Guesclin was chosen as the commander of the French and mercenary forces sent to support Henry. The trust that Charles V and his allies placed in du Guesclin’s abilities was indicative of his reputation at this point, as the constable was given command over a multinational army. He was able to demonstrate his abilities not only in leading a military campaign but also in handling large numbers of often difficult mercenary soldiers.

In Castile, he made use of the same approach he had honed in France. Fighting at the side of Henry in a series of campaigns across Rioja, Navarre, and the Asturias helped turn the balance of the civil war. He was captured in a surprise counterattack by Edward, the Black Prince, at the Battle of Nájera in 1367 (a major English victory) but was ransomed in a matter of months by Henry and the French crown. His return to the field helped swing the momentum of the civil war once more, and by 1369, Henry had been secured on the Castilian throne.

The success of the French-backed Spanish expedition would have long-term implications for English ambitions in Iberia and even at sea. Henry’s firm rule would maintain a close Franco-Castilian alliance, which gave the French navy access to Castilian ports and shipbuilders.

This would be critical in the coming years of the Hundred Years’ War, as a rising English naval power had threatened the French and allied navies at this time. The fact that Bertrand du Guesclin was an integral part of this alliance speaks to his influence outside of France itself.

In the end, his campaigns at home and abroad reshaped the course of the Hundred Years’ War. The steady reconquest of France’s lands weakened England’s position and greatly improved French morale. By avoiding reckless gambits and focusing on careful, coordinated operations, he demonstrated that discipline, patience, and strategic acumen—not spectacle—were the keys to winning wars.

Constable of France

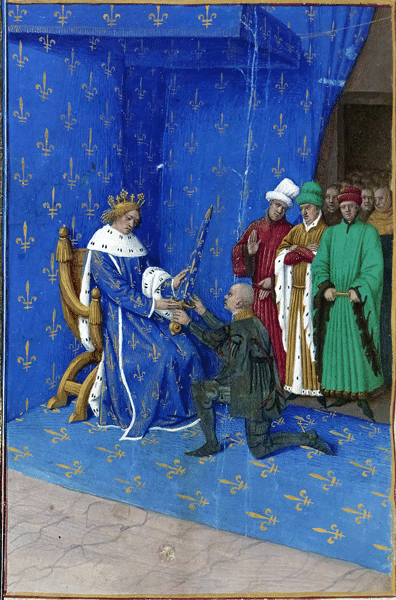

Bertrand du Guesclin reached the pinnacle of his power in 1370, when he was named Constable of France. This was a rare and high military honour, second only to the King himself. It made du Guesclin commander of all others, and it was an astonishing achievement for a man of his background and his non-traditional rise to power.

Chroniclers of the day made clear that the decision was based not on blood or lineage, but on merit, and that it was a true sign that Charles V believed in and trusted him to lead France through one of its most turbulent and volatile periods. For a nation reeling from generations of defeat, du Guesclin’s elevation was a symbol of hope and change.

The honour was not without practical significance. As Constable, du Guesclin would command royal armies, orchestrate forces from the different regions of the country, and have a hand in overall strategy and direction. As such, his close relationship with Charles V meant that policy and strategy could move in concert, without the fissures and interference that had characterized earlier decades. In a king who prized discipline and common sense above all, du Guesclin was a star. Charles once said that “none was more loyal to the realm”, and their unity of purpose became the cornerstone of France’s renewed self-confidence in the late 14th century.

Du Guesclin set about the task of restoring some level of order to the French military, still marked by poor discipline and erratic recruitment. Over the years, he began to build up a more professional fighting force, reducing the need for large, hastily raised levies. He put experienced captains in charge and rewarded skill over title, in a manner that allowed the chain of command to function effectively under pressure. As such, campaigns went ahead with a new level of coordination and effectiveness.

The problem of banditry also had to be confronted. Bands of mercenary soldiers known as routiers roamed the countryside, terrorising both towns and the surrounding countryside. As Constable, Bertrand du Guesclin threw himself into the task of breaking their stranglehold, either by scattering them or by co-opting them into a more structured form of military service. This returned a measure of safety to rural areas and helped regional leaders to reassert their control.

An additional priority was to strengthen the kingdom’s defensive posture. Rather than draining resources into offensives, du Guesclin concentrated on repairing fortresses, walls, and key towns. This vision of sustainable security over high-risk expansion would underpin his campaigns. It was a way of slowly clawing back territory while also shielding people from further harm.

Under Bertrand du Guesclin’s leadership, France entered a period of strategic consolidation and recovery. His reforms helped bring some much-needed order to the country and start rebuilding an army that could push back against English advances. As Constable, he was no longer just a military commander on the battlefield, but a builder of national resilience.

Captivity and Ransom: The Making of a Legend

Bertrand du Guesclin’s rise to fame was shaped not only by the battles he won but also by the way he handled defeat. Captured on several occasions, he turned each setback into a moment that strengthened rather than weakened his legend.

One of the most famous of these episodes occurred in 1364 at the Battle of Auray, where the English emerged victorious. It was here that Sir John Chandos—one of the most celebrated English knights of the age—took du Guesclin prisoner. Chandos was renowned for his skill, honor, and chivalry, and his respect for du Guesclin was immediate. Chroniclers note that the two warriors spoke to one another “as if they were old friends,” a testament to the mutual admiration between great soldiers.

Du Guesclin’s conduct during this first major captivity became the foundation of his reputation. Froissart wrote that he “behaved himself during this misfortune as though he had won the day,” refusing to show anger or shame. His calm acceptance impressed Chandos, who treated him with courtesy, recognizing in him a worthy opponent. For du Guesclin, defeat did not diminish his standing; instead, it revealed a character rooted in resilience and dignity. His composure in the face of loss suggested that he valued honor more highly than victory, prioritizing loyalty and endurance over triumph.

His second major capture came in 1367, during the Castilian civil war at the Battle of Nájera. Once again, du Guesclin’s enemies admired him more after taking him prisoner. Brought before Edward, the Black Prince, he answered questions with blunt honesty, expressing unwavering loyalty to France and to Henry of Trastámara. Contemporary accounts recalled his “terrible and brusque frankness,” a directness that stunned the English court. Instead of weakening his resolve, captivity seemed to sharpen it, confirming the depth of his convictions.

What truly elevated his legend, however, were the astonishing ransoms demanded for—and paid to free—him. At Auray, King Charles V of France contributed heavily to secure his release, declaring that “France has no better knight.” After his second capture, Henry of Trastámara paid a large sum to bring du Guesclin back to the battlefield, even though Henry was still fighting for his throne. The willingness of kings, nobles, and sometimes even enemies to raise enormous funds for his freedom reflected both his strategic importance and the deep respect he commanded.

These ransom episodes revealed the extraordinary value placed on du Guesclin. In an age when captives were often treated as political bargaining pieces, his captors viewed him as a prize of the highest worth. His allies saw him as indispensable. Each time he returned to the field, the price of his ransom—and his reputation—rose. The cycle of capture and rescue created a narrative unlike any other in the Hundred Years’ War, one in which misfortune only enhanced the hero.

Over time, these stories became central to the mythology surrounding him. Chroniclers portrayed him as a man capable of loss without disgrace, a knight who remained loyal and steadfast no matter the circumstances. His captors respected him; his allies cherished him; and ordinary people admired his refusal to yield to despair. By the later years of his life, du Guesclin’s ransom tales had become as celebrated as his victories, proof that his greatness rested not only in military strength but also in character, loyalty, and unshakeable resolve.

Final Campaigns and Death

In the final years of his life, Bertrand du Guesclin remained just as willing to support France’s military needs as he had been earlier in his career, even as his health visibly deteriorated. By the late 1370s, the cumulative effect of decades of active campaigning was evident in his gait and posture. He had clearly aged during the 1360s, and now in the 1370s he seemed even older still. Charles V, however, still called upon his services whenever some area of the realm was threatened by disorder or English encroachment, and the old Marshal responded each time, unable to leave the defense of the kingdom in a state of uncertainty.

Du Guesclin’s final campaigns were in Languedoc and Auvergne, regions disturbed by various rebellions and bandit groups, as well as some remaining English outposts and positions of influence. He was sent to restore peace in these regions, showing the strategic mind and patience for which he had become known. Chroniclers recorded that he sometimes had difficulty riding on horseback and could be seen sweating or coughing in the saddle. He was often laid low by some malady or other, but regardless would continue to be consulted and command as clearly as ever. In some instances, the old Marshal was able to convince a recalcitrant town to open negotiations or capitulate merely through the power of his reputation.

His final campaign began in 1380, with the siege of Châteauneuf-de-Randon. Even in this weakened state, he insisted on taking the field to support the French forces trying to secure the region. As the siege was prolonged, however, his health declined further, and he was moved to a tent on the front lines in a weakened condition. He remained active in advising and planning even as his condition worsened, continuing to work to the very end. Bertrand du Guesclin died on 13 July 1380, before the fortress had officially surrendered.

Musée deu Louvre – Nicolas-Guy Brenet, La mort de Bertrand du Guesclin (13 juillet 1380)

His death was a great shock to the army; both ordinary soldiers and senior commanders mourned the loss of a man who had served the kingdom well during its bleakest years. What happened next became one of the most famous anecdotes of du Guesclin’s life. When the garrison of Châteauneuf-de-Randon negotiated terms of surrender, they requested not to capitulate to the French officers present but instead to surrender the keys of the fortress to the corpse of Bertrand du Guesclin, paying homage to the man they felt had truly vanquished them.

The garrison’s actions would serve as a great honor to the old Marshal, and chroniclers record the ceremony as being unmatched in chivalric pageantry. Bertrand du Guesclin had earned the fear and respect of his enemies over a career that spanned more than three decades. For many, his death served as a symbolic end to an era; a warrior who had been so often inextricably linked with France’s resurgence was given a final, well-deserved moment of homage for his courage and unyielding will.

Burial, Honors, and Immediate Legacy

Bertrand du Guesclin’s funeral was a grand affair, a procession that lasted for weeks, taking his body on a tour of France before its final resting place in the Basilica of Saint-Denis. It is a testament to his influence that he became the first non-royal to be buried among the French kings at Saint-Denis. He was a national hero, and his inclusion in that church so early in his career is a reflection of his status as a great commander and a man whose contribution was believed to have been necessary to the survival of the kingdom during one of its darkest periods.

His tomb was placed near the front of the church, between the tombs of Philip VI and Charles IV. By burying du Guesclin at Saint-Denis, Charles V was making the statement that he had not died for personal or individual causes, but that his life had been dedicated to the authority of the king and to the state. He died with his king’s livery on and was buried with his king’s arms displayed on his tomb.

Contemporaries regarded du Guesclin as a man of great national importance, and he was credited with restoring the national spirit in the French, at a time when they were deeply demoralized. The most famous chronicler of the time, Jean Froissart, described the constable with admiration, praising his devotion to his king, his bravery, and his ability to think and act decisively. His loyalty, determination, and inspirational nature were often highlighted in the work of his contemporaries, and Froissart wrote that he was “a good and loyal knight above all others” who had restored the dignity of a country that had been brought low by years of defeat. Froissart was not alone in his adulation.

In common with other contemporary chroniclers, Froissart portrayed du Guesclin as much a man of the people as a man of his king, highlighting his personal chivalry and kind, considerate way with his troops. He also, as with other chroniclers of the time, focused on his personal character, his fairness as a commander, and his gentleness in victory. As with so many of his contemporaries, he was remembered for his loyalty to the cause of the king, even in the face of great adversity.

His memory became a symbol of the unity and the strength that France was seen to have recovered by the time of his death, at a time when the country was being reunited under one banner.

His death was commemorated by crowds along the funeral route of the tour of France that his body made between 1380 and his interment at Saint-Denis. French commoners in the late fourteenth century had much reason to revere du Guesclin. He had risen from obscurity to the highest rank in France through a combination of innate ability and personal determination. To many Frenchmen, he was a symbol of hope that a kingdom torn apart by war could be restored to some form of order. The decades following his death saw him remembered in this way, and in the immediate term, his death left a significant gap in French life, not just in military terms.

Myth, Memory, and the Legend that Endured

Over time, as the story of du Guesclin’s life and accomplishments became more divorced from official chronicles and entered popular storytelling, particularly in his native Brittany, he became well-known by the name “the Black Dog of Brittany”.

The moniker dated back to his lifetime, when he earned it for fighting in a fashion that was considered tenacious, dogged, and in some ways fearsome, harrying and harassing the enemy and never letting his grip on them slip, as a hunting dog would on its quarry. Some versions claim he was given the sobriquet by the English soldiers who feared his ability to track, harry, and wear down their forces, breaking them more by means of intelligence and endurance than simple brutality.

Other versions of the tale claim that the nickname originated with Bretons who fought alongside him, praising his dogged and unrelenting refusal to give in to his enemy. In either case, the sobriquet caught on because it was seen as both an accurate description of his reputation and abilities, and an omen of his battlefield presence.

The identity also tied easily into Breton folklore, where he was often described as being a warrior seemingly fated for glory, whose strength and cunning bordered on the supernatural. Ballads and epic poems described innumerable battles in which du Guesclin faced overwhelming odds. They yet emerged victorious, fighting in which he came to the aid of the downtrodden, the exploited, and the harassed, and found means to outmaneuver the enemy with a sort of indomitable persistence.

Chroniclers, and later storytellers, embellished his feats of arms and the figure of the “Black Dog of Brittany” became fused with the long and proud tradition of Breton resistance and assertions of independence. Over the generations, these stories and songs were less of a tale of a local champion than a part of the long saga of French perseverance through a century of war.

Du Guesclin’s heroic reputation also became inextricably linked to Breton identity. In this way, communities repeated tales of his loyalty, humility, and refusal to pursue honor or fame for its own sake, creating an ideal of the virtues that Brittany considered essential and a model for individuals to aspire to. The rise of a young man from a poor, distant, often lawless region of France to Constable of France resonated strongly in a realm that had been fractured by decades of war and political instability.

In an era when France often seemed besieged by both foreign invasion and internal division, the life of du Guesclin gave the people hope that resilience and character could triumph even when all seemed lost.

He also became a model for individuals to emulate in a time of great social stratification and hierarchy. The “Black Dog of Brittany” himself had come from a background without the glamour of the French nobility, yet had still succeeded. Du Guesclin showed that birth was no guarantee of success or failure and that through merit, bravery, and fealty, a person could still rise to greater things.

In a time of war and hardship, the example of the “Black Dog” served as a reminder to people that times of hardship could be endured and even overcome, that the future could still be shaped by those willing to take up arms rather than simply by the most fortunate.

Du Guesclin’s approach to warfare also left a lasting legacy. Remembered as a cautious and calculating general, he emphasized attrition, intelligence, mobility, and discipline over chivalric posturing and reckless gestures. The methods he employed—meticulous planning, measured pressure, and avoiding set-piece battles on unfavorable terms—would be lauded by future French commanders. Du Guesclin’s campaigns helped professionalize the French forces and contributed to the development of more regular military units and national defense structures in late medieval France.

In an era of chivalric spectacle and romanticized warfare, he fought and won a style of war that was, in many ways, more modern. His focus on logistics, prepared defensive positions, and coordinated regional defense helped lay the groundwork for a more professional military culture. French commanders who followed him would frequently cite du Guesclin’s campaigns as examples to be learned from or emulated.

Early modern officers studying the Hundred Years’ War would see du Guesclin’s methods and draw important lessons on the deeper structure of war—supply, communication, strategic positioning, and the virtues of patience and planning. In this way, he quietly influenced not just the immediate outcome of the conflict with England, but also the future of French military doctrine.

The life of Bertrand du Guesclin exemplifies the importance of intelligence, tenacity, and unconventional action, both on the battlefield and in the world at large. It is a story that nearly transcends belief, of an awkward, hot-tempered, and often-overlooked boy becoming the Constable of France. The biography of du Guesclin also speaks to the power of an individual’s will in a world where birth, looks, and fate often determined one’s place. Du Guesclin refused to be defined by any of those parameters and instead, through action, loyalty, and an unshakable resolve, defined himself.

Whether through historical acts or the legends that grew around them, the legacy of du Guesclin helped to forge the French national character. The gritty reality of the man who fought, planned, and endured with practical and grim determination became inextricably tied to the mythic “Black Dog of Brittany”, a figure of tenacious courage and unswerving loyalty. Together, the man and the legend form a narrative that has long outlived the battles, sieges, and duels of his age and ensures that the name of Bertrand du Guesclin remains among the most resonant of medieval European history.