Remember, Remember: Guy Fawkes and the 1605 Gunpowder Plot

Guy Fawkes and the 1605 Gunpowder Plot opens with a cold November night and a dark cellar under the English Parliament—an unlikely setting for one of history’s most explosive failed revolutions. On the early morning of November 5, guards found Guy Fawkes and several barrels of gunpowder. The discovery sent shockwaves through the kingdom and revealed a conspiracy that could have erased the monarchy and most of England’s ruling class in one blow. Eye-witnesses described Fawkes as “a man of excellent bodily strength and resolution.” His calm defiance in the face of overwhelming odds and discovery only compounded the plot’s danger.

The failed plot was the culmination of decades of simmering religious conflict under the first Stuart king. English Catholics had been repressed since Elizabeth I took the throne, and there was hope in some Catholic circles that James I would ease their burdens. Instead, Catholics in England saw a resurrection of fines, curtailment of their rights, and public suspicion. Out of this environment emerged a group of men who were confident that peaceful reform was impossible.

The conspiracy that was the Gunpowder Plot was a desperate measure fueled by faith, ambition, and politics. The attempt to blow up Parliament had a profound effect on Britain’s identity and has left a lasting cultural memory, legislation, and an annual reminder: “Remember, remember the fifth of November.”

England on Edge: The Religious and Political Climate

The England that gave birth to the Gunpowder Plot was, of course, an England deeply affected by the Reformation. For nearly 50 years, since Henry VIII had cut ties with Rome, laws had been passed restricting the practice of Catholicism and penalizing those who dissented by fines, forfeiture of property, and social stigma. Elizabeth I had established a network of surveillance that spied on recusants, hounded priests, and controlled all public worship. However, as the laws also allowed dissenters to remain at home if they paid, many families clung to the faith in private, hoping that the next king would be better.

When James I ascended the throne in 1603, he gave many of the faithful pause for hope. Married to a Catholic wife and rumored to be sympathetic, the king’s first years seemed to offer the possibility of reprieve. James suspended the recusancy fines and even won the respect of Catholic leaders in England and abroad for his evenhandedness. However, the honeymoon period for James and the English Catholics did not last long.

The king found advisors who convinced him that lenience could be dangerous. The Catholic community was being watched for the slightest hint of disloyalty, and, in fact, memories of plots both real and perceived were still very much in evidence from the end of Elizabeth’s reign. In 1604, the king reenacted the fines and recusancy laws. The English Catholic community was stunned, and James’s inconsistency was widely seen as a betrayal. The majority of people still chose to practice their religion in peace, but it was becoming harder for all concerned to believe it was possible.

Suspicion and fear of foreign intervention also seeped into the king’s edicts. England’s rivalry with Catholic Spain was increasing, and, with it, a fear that England’s own Catholics were secretly in league with outside enemies.

James wrote in frustration that England was “surrounded by the snares of Rome.” In this atmosphere, all were encouraged to be suspicious, and Catholic loyalty was becoming very hard to demonstrate.

The early years of King James’s reign were tenuous and fast-moving. Catholic families, already wary of the house agents, were being carefully scrutinized for their movements and relations. Many still paid the fines to maintain their traditions and practiced their religion privately. However, James’s wavering stance was breeding further unrest. The younger men were beginning to gather and express frustration that only force would bring about change. The men who would become the Gunpowder Plot conspirators would first gather in this atmosphere of change, fear, and expectation.

The Conspirators: Who Were the Plotters?

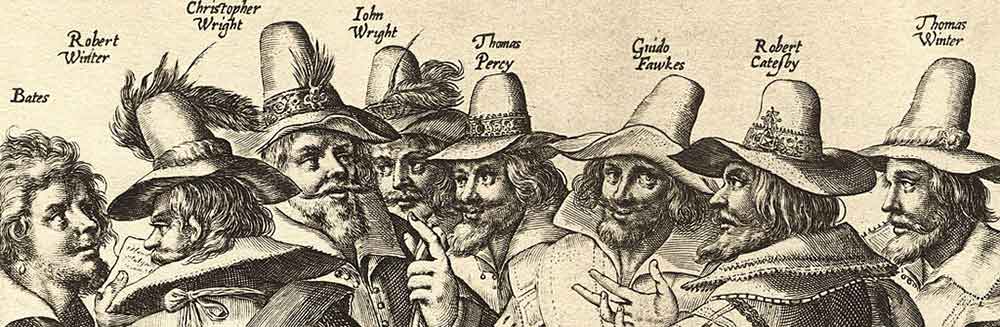

Robert Catesby was a young, charismatic nobleman at the heart of the Gunpowder Plot. The Catesby family had been persecuted for years by England’s anti-Catholic laws. Catesby’s father had been fined many times for recusancy, and the family’s estate had been burdened with penalties for failing to attend Anglican services. These injustices formed Catesby’s worldview and made him deeply resentful towards the crown. He believed that negotiation was not an option. Chroniclers wrote of Catesby as “a man of high courage and resolution.” His fierce determination to act on his beliefs led to a plot of greater scale and ambition than ever before undertaken by English Catholics.

Guy Fawkes was a soldier by training and temperament. A native of York, Fawkes converted to Catholicism as a teenager and travelled to the Spanish Netherlands to fight as a mercenary in Catholic Spain’s war against the Protestant Dutch. He became familiar with siege warfare and explosives during his years in the Spanish army. It was for this reason that Catesby recruited Fawkes to look after and ignite the gunpowder under the Houses of Parliament. A contemporary wrote of Guy Fawkes as “a man of no mean valor,” and even when he was caught, “his face expressed neither pain nor fear.”

A close-knit inner circle of conspirators surrounded Catesby and Fawkes. Thomas Winter was an educated and well-connected member of Catesby’s extended family. Winter was a diplomat, recruiter, and frequently acted as a messenger between the plotters and their external contacts. He travelled to Spain on at least two occasions in search of foreign assistance.

Thomas Percy was a younger member of the influential Northumberland family. Percy had access to political and military networks in London and used his influence to secure a lease on the undercroft beneath the Houses of Parliament. John Wright was a veteran swordsman and a long-time associate of Catesby. Wright, Winter, and Percy were all men of long experience in secret Catholic activity. They had been friends for years and were bound by loyalty, skill, and faith.

Meetings were held in secret at rented houses or on remote estates. The first recorded meeting of the Gunpowder Plot took place in May 1604 at the Duck and Drake Inn in London. It was at this meeting that the core conspirators pledged their oaths of loyalty to each other over a prayer book. The group began to grow as the plot was discussed. Robert Keyes and Christopher Wright were among the first to join, and by early 1605, the membership had grown to include Francis Tresham. Despite coming from diverse backgrounds and having different skill sets, the group was tied together by the belief that a single decisive blow was the only way to restore Catholic rights.

The oath-bound secrecy of the group was intended to protect it, but it also fostered the group’s sense of purpose. Every meeting made them more committed, and every recruit made the circle tighter. By the summer of 1605, the conspirators had become a disciplined unit. They were bound by their faith, their resentment, and their belief that England’s political future hinged on their success. This would carry them all the way to the cellars under the Houses of Parliament—before betrayal unraveled everything.

Planning the Explosion: Inside the Gunpowder Plot

Access to the undercroft beneath the House of Lords was the first problem to be solved. In March 1605, Thomas Percy successfully leased a storeroom directly beneath the chamber in which King James I and the assembled Parliament were to meet for the State Opening. These spaces were typically used for coal and firewood storage, and the arrangement raised no suspicions at the time. The plotters were aware that access to the very center of government would be hard to achieve without attracting attention; their tenancy, arranged through Percy’s connections, was an incredible piece of luck. As one observer would later write, the conspiracy “crept under the very feet of the kingdom.”

Transporting gunpowder to London was a dangerous business in itself. After much difficulty, the conspirators eventually managed to bring 36 barrels, enough to destroy the stone building above and kill all inside. Gunpowder was tightly controlled and regulated, and the conspirators had to buy it in small batches from various sources, taking care to disguise their movements. The stockpile was hidden by stacking the barrels under firewood, iron tools, and piles of coal. Guy Fawkes was in charge of storage, periodically checking on the powder’s state. The explosive had to remain dry and stable; damp powder would not burn, and unstable powder could explode. Either scenario would be catastrophic.

Working in the cramped cellar and under constant fear of being discovered, the conspirators labored at their task. They transported the powder at night, communicated in whispers, and kept the number of men entering the undercroft to a minimum. When Parliament’s opening was delayed due to plague in London, the conspirators feared the Gunpowder Plot would be uncovered, but they had to remain patient. Guy Fawkes was left in charge of the explosives, living in secret as “John Johnson”, a putative servant in Percy’s employ.

The conspirators had aims that reached well beyond a single explosion. The detonation was timed to coincide with the State Opening of Parliament on November 5, to guarantee the presence of King James, the Privy Council, senior bishops, judges, and the leading members of the nobility. The plot’s objective was nothing less than the beheading of England’s Protestant leadership. Catesby and his co-conspirators hoped that such a strike would create enough chaos to spark a Catholic uprising.

In the immediate aftermath of the explosion, the conspirators hoped to kidnap Princess Elizabeth, the nine-year-old daughter of James I, then living at Coombe Abbey in Warwickshire. Elizabeth was to be installed as a Catholic monarch under the guidance of sympathetic nobles. The scale of this ambition—assassination, kidnapping, and political revolution—showed the depth of the conspirators’ desperation and conviction. Catesby reportedly said the blast would “shake the kingdom to its very foundations” and clear the way for a Catholic restoration.

By the autumn of 1605, the conspirators believed they had everything in place. The gunpowder was stored, the cellar locked, and Guy Fawkes was ready to light the fuse. Even as they put the final touches to the plan, however, there were whispers of betrayal—foreshadowing the conspiracy’s dramatic denouement.

Discovery and Betrayal

The unraveling of the Gunpowder Plot can be traced to the best-known letter in the history of the English language, the Monteagle Letter. On October 26, 1605, Lord Monteagle received an anonymous letter that warned him to “abstain this parliament, for God and man hath conceived against it, and they shall receive a terrible blow this parliament.” The note was both general and cryptic, but Monteagle decided to bring it directly to the government’s attention. While the identity of the author remains a point of historical debate, many of the rebels’ sympathizers, most notably Francis Tresham, have been cited as the most likely suspect. In contrast, some modern authors posit that Monteagle forged the letter himself to gain royal favor.

The authorities responded to the letter, which the king took seriously, especially after James I realized the word “blow” was a reference to gunpowder. Attention focused on a property near the House of Lords leased by Thomas Percy. Questions had been quietly asked about that tenancy, since Percy was known to have close relatives who were recusants. A search of the premises was ordered, and on November 4, the King’s men began investigating, but they found nothing. That night, the servant of Lord Monteagle was said to have overheard several men below his lodgings while they were moving firewood, and so the search was redoubled.

A team of investigators was sent into the undercroft of the House of Lords in the early hours of 5 November. A man was spotted standing in the darkness, with a cloak, boots, a lantern, and fuses. When challenged, the man, Guy Fawkes, identified himself as “John Johnson” and claimed to work for Thomas Percy. Taken by surprise, he was arrested and searched, and found to be guarding barrels that had been stuffed with straw and cloth to disguise the gunpowder beneath. Fawkes was bound, gagged, and arrested. A contemporary broadsheet report stated that Guy Fawkes “confessed nothing, yet betrayed himself by his very boldness.”

Fawkes’s arrest shocked the government, which realized that the barrels must contain the mysterious “terrible blow” referred to in the Monteagle Letter. The government immediately ordered arrests, and King James personally interrogated Fawkes. Percy and Catesby were soon in flight, along with other conspirators who hoped to gather support in the Midlands. The plot, however, was already lost.

The point at which Fawkes was discovered was the point at which the Powder Plot began to unravel. The secrecy that had been the great strength of the conspiracy for months was suddenly overcome by a panic of searches, proclamations, interrogations, arrests, and executions. The event was at the same time a triumph for the government and its system of intelligence and counterintelligence, and a justification for more severe laws and persecutions against Catholics.

On the morning of November 5, 1605, Guy Fawkes was being conveyed to the Tower of London. The plot to destroy the English government was over, stopped only hours before it would have caused one of the worst explosions in European history.

Guy Fawkes Interrogation and Confession

Guy Fawkes was brought to the Tower of London in the early hours of November 7. King James I had immediately authorized the use of torture on Fawkes in an attempt to extract information. He gave orders for the interrogators to “begin first with the gentler tortures, and so, as the quality of the offense and the nature of the offender shall give warrant, to proceed to the more severe”.

Fawkes was first manacled and suspended by his wrists, a relatively mild technique. When this did not make him talk, the interrogators resorted to the rack, the Tower’s most feared implement. According to a contemporary account, he “endured and suffered all the torture that could be inflicted on him with admirable constancy”, for which his torturers respected him.

He would not name any of his co-conspirators for almost two days. He readily admitted his own intention to blow up the king and Parliament, but he would say no more. On November 8, after the pain became too great, Guy Fawkes signed a full confession. His signature on the document is barely the same as the one from the previous day, written in a jagged, quivering hand. Some historians consider it the most disturbing artifact of the plot.

With Fawkes talking, the government acted quickly. He named several of the co-conspirators, and it was now clear who Robert Catesby, Thomas Percy, and the Wright brothers were. Over the next few days, royal forces raided the Midlands to prevent the surviving plotters from escaping. A few of them died in a firefight, including Catesby and Percy at Holbeche House. The rest were caught, bound in chains, and brought to London for interrogation.

Fawkes’s confessions led the government to further safe houses and participants. Other members of the Catholic community were investigated and, in many cases, arrested, interrogated, or heavily fined. The unraveling plot was used by government officials to point to a larger Catholic threat in the months that followed. By the end of November, the entire plot was known to the government, which had the resources and will to publicize it to the fullest.

Guy Fawkes, physically and mentally exhausted but resolute, was under constant watch as the crown prepared to try the Gunpowder Plot conspirators in public trials. The capture, confession, and information from Fawkes were such that the Gunpowder Plot, intended to destroy the English government, became one of the most documented failed plots in British history.

The Aftermath: Trials, Executions, and Public Spectacle

The surviving plotters were tried before a court crowded with noblemen and foreign diplomats in January 1606. They faced vague charges of treason, sedition, and attempting to “levy war against the king, the queen, the prince, and the whole body of the realm.” The prosecution offered lurid descriptions of the plot and paraded the barrels of gunpowder as evidence of the plan.

The arrest of Guy Fawkes, now blackened and bloodied from torture, beneath Parliament was also retold in court. Government statements made clear that the plotters were Catholic and the entire conspiracy a foreign-inspired attack against the English monarchy. Witnesses noted the apparent lack of emotion in the condemned men. Guy Fawkes, sick from torture, remained silent through the proceedings.

The court quickly determined all of the prisoners guilty. Their punishment was obvious. The usual sentence for treason was hanging, drawing, and quartering: a gruesome form of execution intended to intimidate the general public. On January 30 and 31, the plotters were carried through the streets to St. Paul’s Churchyard and Old Palace Yard, where crowds gathered to see the proceedings.

The government used every means of propaganda to assure the English public that the Gunpowder Plot was “the most cruel and detestable treason that ever was imagined.” Some of the doomed men prayed aloud, some remained silent. Guy Fawkes was set to die last, and while on the scaffold, he leapt from the trapdoor, breaking his neck and escaping some of the full fury of the executioner’s blade.

The reactions of the English public were complex. A powerful combination of fear, triumph, and anti-Catholicism shaped many reactions. Pamphlets and sermons promoted the idea of God’s direct intervention at the last possible moment to save the king. Bonfires were lit across the kingdom, and Parliament determined to establish November 5 as a national day of thanksgiving. This story—the government’s tale of steadfast Protestants saved from destruction—molded the image of the plotters as dastardly villains.

For England’s Catholics, life became even more difficult in the years and decades after the failed plot. The small minority of English Catholics was already subject to recusancy fines and other limitations on worship and behavior. After 1605, new and stricter laws were passed. Catholics were expected to take oaths of allegiance to the crown, foreign Catholic priests were banished from England, and recusancy fines were increased. Ordinary Catholic families (and the majority of Catholics disapproved of the plot) were suddenly viewed as threats. Suspicion and fear were rife. Catholicism and treason were linked in the minds of English Protestants.

The legacy of the Gunpowder Plot affected English life for generations. The plot was used both as a rationale for stringent anti-Catholic policies and as a parable against the dangers of internal enemies. The memory of the trials and executions outlasted the men themselves. November 5 and the story of Guy Fawkes would remain essential parts of Britain’s cultural and political life.

Legacy of November 5

The months following the foiled plot were also dominated by parliamentary action. Seeking to prevent the conspiracy from slipping into obscurity, Parliament passed the Observance of 5th November Act in 1606, which decreed an annual day of thanksgiving for the king’s deliverance. Initial commemorations were modest affairs of church services and public meetings, but gradually became raucous public holidays.

Bonfires were lit in towns and villages up and down the country, and effigies (initially of Guy Fawkes, but eventually of other political and religious figures) were tossed into them. By the 18th century, fireworks had become a staple of the celebrations, and the evening was now a grand display of noise, light and popular celebration.

Guy Fawkes’s place in the national consciousness also evolved. For hundreds of years, he was remembered as the archetypal traitor, a reminder to all that disobedience to the crown was punishable by gruesome death. Children sang “Remember, remember the fifth of November”, and effigies of Guy Fawkes—mockingly dressed in outlandish costumes and stuffed with firecrackers—were carried through the streets before being burned.

But gradually the Fawkes image began to change as cultural norms shifted. Many 19th- and 20th-century writers started to re-evaluate the conspirators’ motives and portrayed Fawkes not just as a villain but a victim of religious persecution. In some accounts, he became less a terrorist and more a misguided idealist.

But it was not until the 21st century that Fawkes’s image shifted once again, in the form of a Guy Fawkes mask. Popularised by the graphic novel and subsequent film V for Vendetta, the stylised mask has become an international icon of resistance to tyranny. Movements from Occupy Wall Street to anti-government protests worldwide have embraced it as a symbol of resistance, anonymity, and bottom-up power. It is a sign so globally recognised today that Guy Fawkes is more famous now than at any point since 1605.

The Gunpowder Plot’s path to becoming one of the most famous conspiracies in British history and the global icon of protest has been centuries in the making. In a sense, it succeeded where it otherwise failed; turning a failed plot to become an annual day of thanksgiving, folk festival, and finally a global political symbol has firmly embedded it in the national psyche.

November 5 has endured not just because of what might have happened under Parliament, but because every generation since has found new significance in it. It is a lesson in loyalty to the crown, a cautionary tale about extremism or, perhaps most of all, a reminder that resistance—whether armed or peaceful, criminal or not—remains a force that shapes our history.