Charlemagne: The Warrior King Who United Europe

Charlemagne was a leader with the central role in history where the paths of war, politics and religion converge. He expanded his power and influence over the greater parts of Central and Western Europe. In a single lifetime, the deeds of Charlemagne by sword and of his tireless work as a diplomat made him the foremost ruler to have unified a divided continent by any means possible. The chroniclers who witnessed the times about him are speaking as much of a powerful and prophetic ruler, as of a merciless warrior and a shrewd statesman.

He left more than a legacy of conquest. He inspired a European identity cultural and political. Uniting many different peoples under one royal crown, sponsoring the Christian Church, and instituting administrative reforms, Charlemagne redefined the landscape of medieval society. The renaissance of knowledge, sponsored by Charlemagne, that came to be known as the Carolingian Renaissance, would ensure that his impact was far reaching and would not be restricted to the martial realm. His legacy lives not only in the memory of the empire he built but in the very idea of a Europe.

Early Life and Ascent to Power

Charlemagne was born circa 742, a member of the Carolingian dynasty. The Carolingians were a Frankish noble family that had taken prominence among the Frankish nobility over the generations. Charlemagne’s grandfather Charles Martel had earned fame for halting the Muslim advance into Europe at Tours in 732. This victory positioned Carolingian rulers as champions of Christendom. The dynasty, by the time Pepin the Short occupied the Frankish throne in 751, had already outshone the decaying Merovingian kings. Charlemagne would go on to ascend to the kingship within this already established background of legitimacy and authority on which he would build his rule.

The kingdom was divided between the two of them, as was custom in Frankish tradition, when Pepin the Short died in 768. It created a dynamic where Charlemagne’s portion was more susceptible to foreign invasion and exposed more to invaders and where Carloman’s portion was more stable with a centralized control.

This was one of the few events recorded for the brothers, with contemporary sources suggesting they did not get along well. Frictions between the two were such as to threaten the kingdom’s stability. But the sudden death of Carloman in 771 left Charlemagne as the sole Frankish ruler. This sudden change in circumstances provided the chance for Charlemagne to focus on unifying the kingdom under his rule to avoid other dynasties’ eventual fate.

Charlemagne moved with urgency to consolidate his control of the realm. He employed a balance of coercion and diplomacy to ensure nobles’ support and bolster his power. Charlemagne drew tighter to the Church, re-emphasizing Carolingians as the champions of Christianity. The alliance invested his rule with a sacred quality, placing him above kingship and enabling him to present himself as one with divine backing. He also shuffled local administration to make regional administrators answerable and prevent rebellions that could challenge his kingship.

Charlemagne’s ability to combine military might and effective government separated him as more than just heir to a powerful dynasty. The power to do this, as he demonstrated at a young age, could command armies, parley with enemies, and provide an aura of continuity. These traits not only established him as King of the Franks but also enabled him to expand into one of medieval Europe’s largest empires. By the late 770s, his kingship was already reconfiguring the political landscape of Europe, and his name as a force to be reckoned with was set in stone.

Annexation of the Lombard Kingdom

One of the earliest and most significant campaigns in Charlemagne’s long military career was that waged against the Lombards in northern Italy. The Lombard Kingdom, centered on the city of Pavia, had long been a dominant power in the region and was frequently a threat to the Papal States. Pope Adrian I, faced with Lombard aggression, sought the assistance of Charlemagne. As a political ally and protector of the Church, Charlemagne entered Italy in 773 and led his armies over the Alps in a bold and strategic move that would signal his martial prowess. The campaign would become one of the defining moments of his reign.

The siege of Pavia became the campaign’s defining episode. Charlemagne’s forces encircled the city for almost a year, attempting to starve out its defenders. Despite its strong fortifications, the city was ill-equipped to withstand a protracted siege. The Lombard King Desiderius, who had previously attempted to secure his dynasty through marriage alliances with Charlemagne’s family, was forced to surrender in 774. Chroniclers like his biographer Einhard called the episode the campaign’s culminating point by stating that Desiderius was exiled as Charlemagne claimed the title “King of the Lombards” for himself.

Charlemagne’s victory over the Lombards was not merely a military conquest, it was also a political one. Donning the Iron Crown of Lombardy, he placed himself as the new King of Italy and had in effect united two great kingdoms under a single ruler. This gave him control over the strategic Alpine passes and solidified his hold on northern Italy, enabling him to control and to expand the economic base of his empire through trade. By conquering the Lombards, Charlemagne cemented his alliance with the Pope and reinforced his role as the protector of Christendom.

The assimilation of the Lombards into his empire also demonstrated Charlemagne’s administrative acumen. Rather than dismantling Lombard institutions, he incorporated them into his own administration, creating a blend of native and Carolingian practices. Lombard nobles who pledged their loyalty to him were allowed to retain their positions. In exchange for their continued support, these nobles were expected to assist in the smooth succession and prevent any uprisings. This strategy allowed him to solidify his control over Italy and provided a template for future expansion.

The conquest of the Lombard Kingdom elevated him from being just a regional ruler to being an ambitious monarch with imperial aspirations. It extended his dominion far beyond the borders of Francia and provided him with a foothold in northern Italy, which would become a cornerstone of his empire. The victory at Pavia established him as a ruler who could skillfully combine military might with political acumen and religious sanction. The new title and authority that he took would later be the foundations on which he would build his larger imperial ambitions.

Campaigns around Lombardy, Spain, and against the Avars

The conquest of the Lombards was only the beginning of Charlemagne’s continental ambitions, and his armies became the vanguard of conquest as much as they were a means of consolidation. To the north, still in Italy, his war against the Lombards was as much a matter of establishing a permanent Frankish base as it was of destroying King Desiderius. Charlemagne returned to Italy time and again, as much to reinforce the Frankish position as to make sure that the crown of Lombardy never strayed far from his own. The capture of strategic cities like Verona or Pavia drew the country closer to his own lands and solidified his role as a defender of the Papacy.

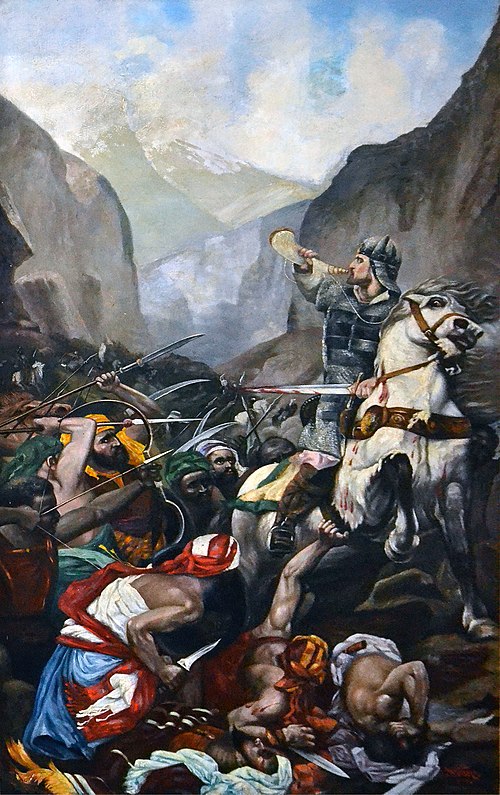

To his west, Charlemagne gazed across to the Iberian Peninsula, where Muslim rule within the independent al-Andalus emirate was both an invitation and an opportunity. It was he who first led his famous campaign into Spain in 778 to extend Frankish power beyond the Pyrenees. He was initially successful in taking cities all the way down to Pamplona, but the withdrawal to the north ended in disaster at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, where Basque raiders ambushed and killed the Frankish rearguard under the legendary Count Roland in the Breton March.

Although a military humiliation, this episode became part of the epic song, the Song of Roland, which would raise Charlemagne’s campaigns to heroic proportions, and serve as a warning to all who would expand into a foreign and hostile land.

To their east, Charlemagne had the Avars, a large nomadic confederacy that had established itself within the Carpathian Basin. The Franks began a series of campaigns with the Avars as early as the 790s that lasted nearly a decade. The heaviest blows were dealt when Charlemagne’s armies broke into the Avar “Ring,” their fortified camp, and looted a vast amount of treasure. The chronicles said that there was so much booty that it would last years and was to be shared among the monasteries and nobles. This victory obliterated the Avars and pushed Charlemagne’s borders deeper into Central Europe.

Force and negotiation usually went together with him; he granted native rulers powers if they promised fealty. This policy allowed him to incorporate many disparate people under a single crown and to bring a sense of order to a divided world.

The campaigns in Lombardy, Spain, and against the Avars all reinforced Charlemagne’s identity as a Christian king and a unifying monarch. These wars were often presented as a mission to make Christendom great. Victories over pagan and Muslim foes were divine triumphs that solidified his position as a defender of the Catholic Church.

Saxon Wars: Decades of War and Christianization

None of Charlemagne’s many wars was so protracted or so bloody as his Saxon Wars. Lasting for more than 30 years, from 772 to 804, they pitted Christian Franks against the pagan Saxons of northern Germany. The Saxons fiercely resisted Frankish rule and, when forced back, they retreated to the swamps and forests, then re-emerged to raid when the Frank armies left. Charlemagne responded with ruthless determination, carrying out campaigns that were virtually annual and which aimed to do more than just defeat the Saxons: they aimed to Christianize them too.

The war proper began in 772, with Charlemagne attacking and destroying the Irminsul, a religiously holy Saxon tree which was seen as connecting heaven and earth. The chronicler Einhard described this as a symbolic attack on Saxon religious centers. Frankish armies continued to win repeated victories, including taking over strategic centers like Eresburg, but the Saxons continued to stubbornly refuse to submit unconditionally, encouraged by a leader of Saxon resistance, Widukind. Widukind himself urged his countrymen to rise up even after signing a truce.

Charlemagne was ruthless in Saxony. In 782, in response to a Saxon uprising, he ordered the execution of thousands of Saxons at Verden. This was his attempt to break Saxon resistance, and is by far the most notorious episode of his reign. From this point forward he focused on using a combination of military and diplomatic pressure: settling loyal Franks in Saxon territories, requiring oaths of loyalty, while also sending priests and bishops to establish churches and schools.

The turning point was Widukind’s own surrender and baptism, which took place around 785. Widukind’s baptism was significant as part of the broader cultural transformation which Charlemagne was hoping to achieve: the replacement of Saxon paganism with Christianity, as the new basis for their identity as Frankish subjects. There were further rebellions in the years that followed, but continued pressure through campaigns, resettlements, and missionary efforts gradually wore down Saxon resistance and the wars were ended by 804, with Saxony firmly incorporated into the Carolingian Empire.

The Saxon Wars had a lasting impact on Europe. They cemented Charlemagne’s reputation as a ruler who was not afraid to use both sword and cross to unify the various peoples under his rule. The wars also spread the influence of Christendom into northern Europe, thereby laying the foundations for the later Christianization of Scandinavia. At the same time, they also exposed some of the underlying fault-lines of Charlemagne’s empire in the integration of conquest, religion, and government. The Saxon struggle can be seen as in many ways the most acute form of the problem of creating unity in a continent divided by culture, belief, and tradition.

Faith & The Pope

Faith was the constant running current of Charlemagne’s life and reign. One of the most significant and fruitful relationships in his career was forged with the Church. As early as his ascension as King of the Franks, Charlemagne understood that a connection with the Catholic Church would not only enhance his spiritual standing, but his political status as well. The Papacy welcomed a strong ally to back Rome and bring protection and Christianity to the wider world.

Charlemagne advanced the spread of Christianity strategically. In territories where he won military success, such as Saxony and Bavaria, building churches, ordaining bishops, and establishing schools became a priority for Charlemagne. The conversion of the newly subjugated people forged a common religious identity that unified his empire. Chroniclers often extolled Charlemagne as a pious man of God (and he was; he was reported to be a regular attendant at Mass and supporter of missionary work), but Charlemagne was no fool and could see how practical religion could be in solidifying his position of power.

Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican – RAFFAELLO Sanzio

The most legendary event of his alliance with the Church is of course on Christmas Day in the year 800, when he was anointed and crowned “Emperor of the Romans” by Pope Leo III at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. This was more than a blessing from the head of the Church. The title of Emperor had not been claimed in Western Europe since the collapse of Rome nearly 300 years before. Charlemagne may or may not have been surprised by the coronation (sources differ), but there could be no doubt about the historical significance of the event. In one moment, the foundations of Europe as it would be known for centuries were irrevocably altered.

The coronation was a political statement as much as a spiritual one. The act and title tied Charlemagne to the ancient tradition of Rome. Pope Leo III anointing Charlemagne was as much a message to the people as it was to history books; The Church had the ability to make and unmake rulers, and in crowning Charlemagne, the Pope was making it clear that a Christian ruler was a protector of the faith and a father of his people. The relationship between Church and State which it established would be a defining feature of European politics for generations to come.

In his reliance on the Church for spiritual legitimacy and the power that the Church could provide, Charlemagne was not averse to exercising influence and control over its own internal matters. He convened church councils, influenced doctrine, and encouraged a uniformity of practice and belief. Charlemagne saw and utilized the Church as much as an instrument of government as a partner in faith. In his capacity as both servant and master of the Church, Charlemagne set the stage for the contest of wills between popes and emperors to come.

Charlemagne was no longer just a warrior king. He was now the quintessential medieval king: warrior, statesman, and servant of God. The image of Charlemagne, crowned by the Pope, sword in one hand, cross over his heart, became a symbol of a ruler who would, by the joining of faith and the power of the sword, bring order to a chaotic world.

Governance and Reforms

Charlemagne understood that to maintain a diverse empire made up of many different people and territories, he would need more than just military might. His was a government of the sword and the pen, and from the beginning of his rule, he set about ordering, stabilizing, and uniting a world that was often chaotic and disparate.

Charlemagne’s innovations began with his approach to governance and administration. He appointed counts, or regional officials, to act as his deputies, responsible for justice, defense, and taxes within their counties. These local officials were essentially the king’s representatives in the field, tasked with implementing the will of the central government. However, to ensure that the counts remained loyal and efficient, Charlemagne also established the missi dominici, or “envoys of the lord ruler,” a system of itinerant royal inspectors who would travel the empire, auditing local administration and reporting back to the emperor. This early form of checks and balances was key to maintaining control over the far-flung territories of the empire.

He also sought to standardize and codify laws across his empire, creating a more unified and predictable system of justice. Charlemagne merged older tribal laws with Christian ethics and ordered them to be written, revised, and uniformly applied across his realm. His capitularies, or royal edicts, often focused on legal reforms and the establishment of standard justice for all his subjects. While the practical enforcement of these laws was often uneven due to the vastness of his empire, the intention was clear: Charlemagne’s kingdom was one of moral as well as military order.

Education became another of Charlemagne’s primary concerns, both as a tool of statecraft and as a moral obligation. An effective empire needed educated administrators, both secular and clerical. To this end, he brought in Alcuin of York, an English scholar, to oversee the palace school at Aachen. Under Alcuin’s tutelage, the curriculum would eventually come to include the seven liberal arts: the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, logic) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). Charlemagne not only wanted his courtiers to be literate and knowledgeable but also his clergy. Despite his age, Charlemagne himself took to learning reading and writing in his later years, a testament to his commitment to this cultural endeavor.

Charlemagne’s efforts in these areas would give rise to the Carolingian Renaissance, a period of cultural and intellectual revival that sought to preserve classical learning and Christian texts. But the renaissance was not limited to scholarship and education. Architecture, visual arts, and music also saw a significant revival and standardization during his reign.

The Palatine Chapel in Aachen, for instance, was both a feat of engineering and art that symbolized Charlemagne’s vision: a fusion of Roman imperial power, Christian sacredness, and Frankish identity. The standardization of coinage and even liturgical music helped to create a cohesive imperial culture.

Charlemagne also encouraged the development of a standardized script, known as Carolingian minuscule, which was clearer and easier to read and copy. This script reform helped preserve many ancient texts that might have otherwise been lost and made education and literacy more accessible throughout the realm.

In all these endeavors, Charlemagne demonstrated that effective leadership was as much about the pen as it was the sword. It was not just about how much land he conquered, but about how he ruled and reformed, and how he imagined a better, more united, and more enlightened Europe. His legacy, therefore, was not only in the empire he built but also in the model he provided for future kings and emperors who would look to what Charlemagne had achieved with awe and aspiration.

The Enduring Legacy of Charlemagne

The legacy of Charlemagne had a profound impact on the history of Europe. He was not only a conqueror but also a visionary who laid the foundations of modern European identity. Although his empire did not survive in its original form, the institutions, ideas, and systems he established endured.

Charlemagne is remembered as a unifier, a builder, and a model of Christian kingship. His influence can be seen in the development of feudalism, the revival of classical learning, and the concept of Europe as a shared cultural space. Even his sword, Joyeuse, became a legendary relic, used in French coronation ceremonies as a symbol of royal authority and continuity.

His life is a powerful example of how one leader’s vision, courage, and persistence can shape the destiny of nations. By integrating faith with governance, warfare with learning, and tradition with reform, Charlemagne built more than an empire.