Charles Martel at Tours: The Hammer of the Franks

The year 732 found Charles Martel in a pivotal position on the world stage. The Umayyad Caliphate’s armies, freshly victorious in Iberia, were pushing north into Frankish Gaul. The heart of Christendom was aflame, and Abdul Rahman al-Ghafiqi, an intrepid Muslim commander, was making a push into the continent to conquer it. In the 300 years since the fall of the Roman Empire, Europe had splintered into bickering factions and fiefdoms. It was a weak state. But the Battle of Tours and Poitiers would put a stop to this.

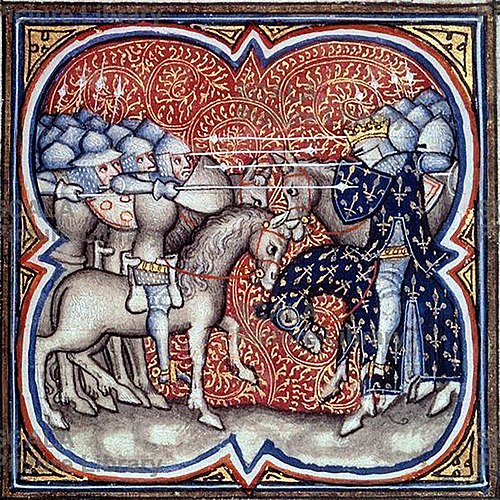

In the fight to hold his own patch of Europe together, Charles Martel became known as “The Hammer”. The Frankish mayor of the palace, who had absolute power in the kingdom, united disparate tribes in revolt against the heathens and reorganized the chaos into an organized fighting force. He met the Umayyad Caliphate’s general, Abdul Rahman al-Ghafiqi, and his army near the city of Tours. The organized and decisive Martel decimated the invaders and pushed them back into Iberia. His single, brilliant move not only saved a fractured Europe from conquest but also helped create the Carolingian Empire. The same move singlehandedly elevated him from tribal warlord to the world’s most outstanding defender of the West.

Europe Before The Battle of Tours and Poitiers: A Continent Divided

Europe in the early 8th century had not yet recovered from the fall of the Western Roman Empire three centuries earlier. A unified body politic, administered by law and secured by infrastructure, had given way to a patchwork of competing kingdoms, warring tribes, and local warlords. Authority was localized, information scarce, and most men’s allegiances did not run much farther than the walls of their nearest castle. Petty warfare and shifting alliances across Gaul, Saxony, and Lombardy had taken the place of the centralized government that Rome once provided, and a new order was starting to take shape, both political and religious.

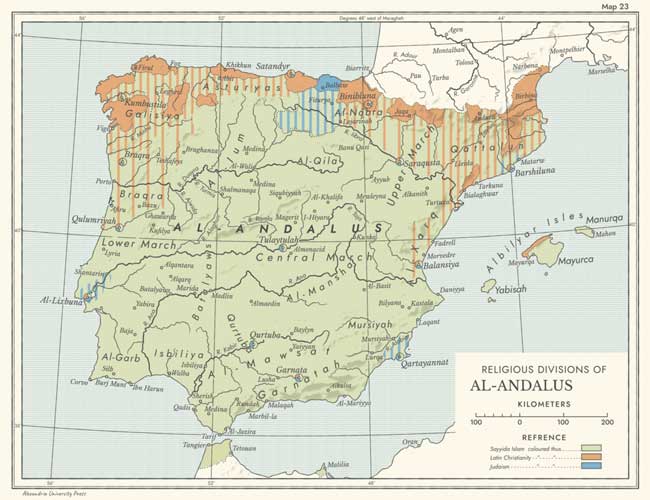

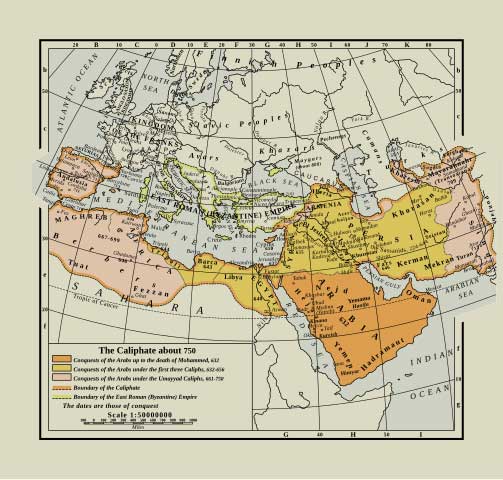

As Europe stagnated and squabbled, a new and powerful empire had taken shape across the Pyrenees. The Umayyad Caliphate, which stretched from Persia to the Atlantic, had stormed through North Africa and conquered almost all of the Iberian Peninsula. Muslim armies had crushed the Visigoths of Spain and turned Al-Andalus into a bastion of Islamic strength. Their leaders were ambitious and confident, and they looked north to the plains of Gaul as their next objective. Raids into Aquitaine and southern France by the early 730s had become more frequent and more brutal.

The Christian West was nowhere near ready to meet such an organized and motivated enemy head-on. Although Islam had provided the Caliphate with a common cause and brought its subjects under a standard banner, Europe was still riven with differences in language, faith, and ambition. The Pope in Rome commanded spiritual respect, but little in the way of military or political power, and local rulers bickered over power and position. A common European identity had not yet formed, and most men understood little of the concept of Christendom.

Charles Martel: The Making of “The Hammer”

Charles Martel’s meteoric rise to power was born of chaos. The illegitimate son of Pepin of Herstal, he was born circa 688, in a realm ruled in the name of the decrepit Merovingian kings by powerful mayors of the palace. When Pepin died, factions of Frankish nobility split into feuding camps, and the kingdom devolved into open civil war. His stepmother’s partisans imprisoned Charles, but he escaped and raised an army from his loyal partisans.

In a series of violent, destructive campaigns, he wiped his rivals from the face of the Earth, reuniting the Franks under his banner. His rise to power was not a story of noble inheritance or legal right. It was a tale of blood and violence—of a man who by his will and his strength made himself master of all Gaul.

Secure in his position, Martel set about remaking the Frankish military. For generations, the armies of the Franks had been levies—peasants and warriors who put down their tools and took up the sword for the duration of a campaign. Charles recognized that such an army was ill-equipped for sustained war, particularly against invaders as fierce and aggressive as the Muslims. He instead created a professional fighting force, outfitting and training an elite body of warriors capable of warfare year-round. To pay for these professional troops, he controversially plundered church lands and redistributed them among his fighting men, justifying this act as a sacred duty of defense.

Martel’s innovations were revolutionary. He saw the power of cavalry over infantry and heavily invested in heavy cavalry. Well-trained and well-armed horsemen equipped with lances and mail armor became the prototypes of medieval knights, shock troops able to strike from the saddle and break enemy lines. By pairing heavy cavalry with defensive infantry formations, Martel built an army both able to defend against incursions and powerful enough to strike against numerically superior forces. Martel’s reforms would shape European warfare for centuries.

Martel was not just a great military leader; he was also a great politician. He worked to unite the Franks under not just the authority of his rule but the divinely sanctioned authority of his cause. The Frankish kingdom was unified under a banner of common, spiritual purpose. The defense of Christendom against pagan and Muslim aggression became both the political and the religious justification for Charles Martel’s rule.

As the Islamic armies rolled over Iberia, Martel’s victories took on a new importance as symbols of his divine protection. Charles Martel was now not just the kingmaker of the Franks; he was the savior of Christendom at a time when no one else was capable or willing of defending it.

In this time, Martel was given his nickname “The Hammer.” Chroniclers painted him as a man who with the force of a hammer would strike down his enemies and smash them into the dirt. Revolts, Muslim invaders, other warlords—none could stand before the Frankish hammer. The nickname was a portent of fear and respect. Martel was more than just a Frankish warlord. He was the symbol of Europe’s resistance; he was the hammer that beat back the enemies of Christendom, a man whose name and deed would be known through the ages. By the time of the Battle of Tours and Poitiers, Martel was more than a man—he was an idea, the hammer of Christ.

The Road to Battle

By the early 730s, the armies of the Umayyad Caliphate had conquered nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula. The region from the Pyrenees Mountains to the Strait of Gibraltar was under Muslim rule, and the Arab governors, known as emirs, sought to enrich themselves by raiding further north. Victorious in battles against Visigothic Spain, which had capitulated in less than a decade, the Umayyads had set their sights on the rich farmlands of southern Gaul. Abdul Rahman al-Ghafiqi, an emir of the Umayyad dynasty, had taken charge of the forces and led them to triumph in Hispania. The Muslim forces, well-organized and battle-hardened, saw their next destination as a prime opportunity for both plunder and further expansion.

In 732, the Arab armies crossed the Pyrenees and ravaged the region of Aquitaine, one of the few areas of Gaul still outside their control. Under the command of Duke Odo, an independent-minded and powerful Christian warlord, they captured and pillaged the city of Bordeaux, then defeated his army.

Abdul Rahman then plundered the region, his raid bringing terror to towns and monasteries. The city of Tours, which held the shrine of St. Martin, was his next objective. St. Martin was one of the most popular saints in Western Christendom. If the Muslim forces captured Tours, the city and its holy sites could be turned into a garrison to consolidate the Arab power further into Europe, providing a base for further expansion.

Alerted to the threat, Charles Martel was in no mood to give up his territory to these raiders. He raised his Frankish warriors and sent messengers to his Burgundian allies, calling them to his standard. Martel had not had the resources to amass an army as large as that of the Umayyads, but his soldiers were well-trained, experienced, and motivated by their leader and their faith.

Instead of waiting for Abdul Rahman’s army to push further into his lands, Martel took the initiative, knowing that if he could defeat them, they would be less likely to attack him again. It was a bold move, one that would pit the Frankish infantryman against the Arab cavalryman in a contest to the death.

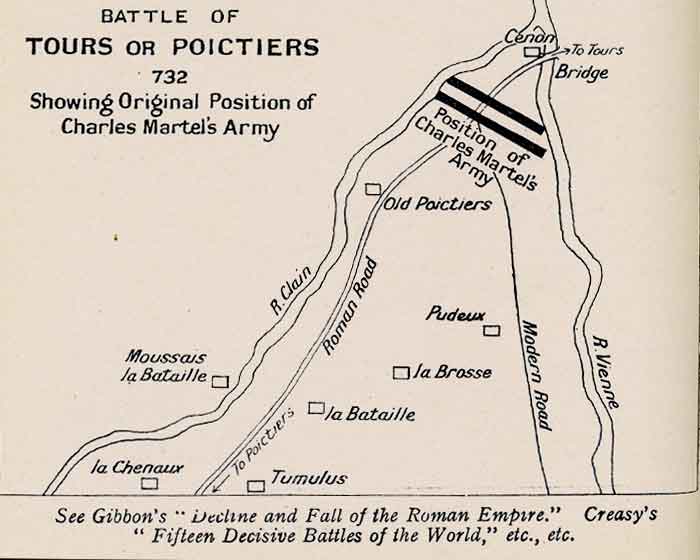

Martel chose his terrain carefully. The area north of the river Loire around the town of Poitiers, a passageway through the high, wooded ridges of the region, was ideal. It allowed him to bar the way to Tours and prevent the Umayyad army from outflanking him. It also gave him a strong defensive position with high ground on which to form up. He arranged his men into solid, phalanx-like formations, tight arrays of shields and spears that would have to be pierced before they could be defeated. His army, heavily outnumbered but united by a common goal, knew that there could be no retreat.

For a week, the two armies faced each other on the fields around Poitiers. Waiting for each other, both armies endured a cold October, each hoping the other would give in first. In the end, it was Abdul Rahman who was more eager, more anxious for the riches of Tours. On October 10, 732, the armies clashed. Charles Martel’s decision to stand and fight at that moment at that place would be a turning point, a culmination of both luck and calculation. The road to Tours had been long, and its fields had been paved with conquest and chaos, but on them, the die would be cast.

The Battle of Tours and Poitiers (October 732)

In October 732, the two armies met at the city of Tours. Charles Martel had at his disposal an army of well-trained infantry, drawn from the heartland of Gaul. At the same time, Abdul Rahman commanded an experienced cavalry force of the Umayyad Caliphate, fresh from their advance across Gaul, undefeated and unopposed from the Pyrenees to the Loire. The Umayyad forces were numerically superior, but Charles’ Frankish army was better positioned on the high, wooded ground, while his tactics would mitigate the speed and power of the Muslim horse.

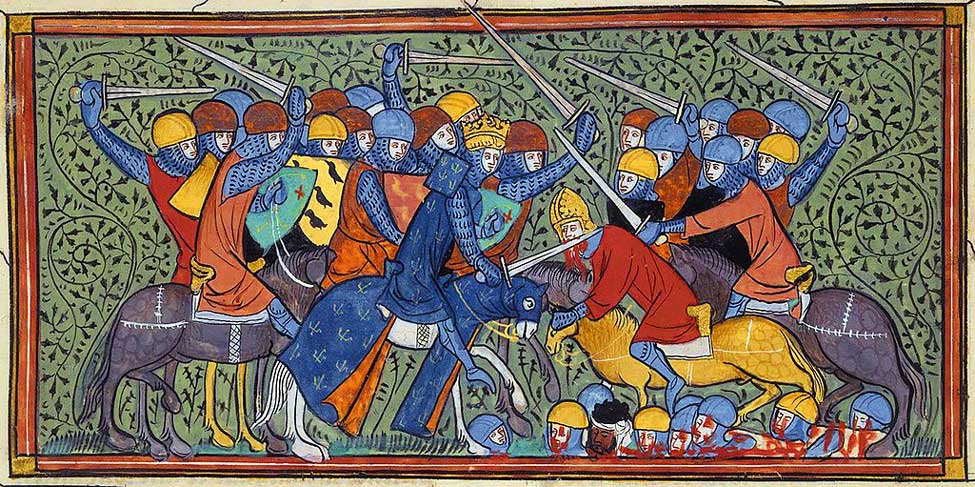

Martel had taken up a position on a ridge, behind a bank and a ditch, a mile and a half from the town of Tours. The Muslims approached, skirmishing with the Franks’ forward guard. Abdul Rahman ordered a general advance, and the battle began in earnest. Martel’s Frankish infantry formed a phalanx with their spears and shields, ten or so men deep in a broad line. The Umayyad cavalry charged, striking the Frankish line, only to be thrown back by the dense formation of shields and spears.

The Franks lacked cavalry, so Martel’s troops bore the brunt of the charge, stood their ground, and waited. As the Arab horses struck and fell back, the Franks formed a line as “still as a wall,” an impenetrable mass of men. Despite being outnumbered, the two armies fought a pitched battle for seven hours, locked in close-quarter combat.

To medieval chroniclers, the Battle of Tours and Poitiers would represent a turning point, a clash of civilizations, of Christianity against Islam, of a Europe besieged by an infidel army. To contemporary sources, such as the Chronicle of Fredegar, the battle was a “great slaughter of the Saracens” and medieval tradition would later celebrate Martel as the savior of Christendom. In reality, the struggle was less about religion than it was about power and survival. Nonetheless, the narrative and sense of a Europe fighting for its cultural identity would define the legacy of Tours.

Hours passed, and the Arab cavalry attacks grew more desperate. Neither side had made significant gains, but eventually, towards late afternoon, the Muslim vanguard became aware that Emir Abdul Rahman had been killed in the fighting. The news caused panic in the Muslim camp. Believing they were about to be surrounded, and fearing for their captives and the plunder they had already taken, elements of the Umayyad army began to retreat.

Martel’s forces pressed home the attack, their tightly-packed formation beginning to push the wavering Muslim line back. The battle of Tours was won. Darkness saved what was left of the Umayyad army, and by morning, the Franks readied themselves to renew the attack. They found the Umayyads had disappeared, their camp abandoned under the cover of night. The Arab army, in rout, slipped away to the south and the safety of Iberia.

Martel did not attempt to pursue the retreating Umayyads. In the end, his victory was total. The field was covered in bodies, and the might of the Umayyad Caliphate had been broken. It was an astonishing victory. Against all the odds, Charles Martel, the Hammer, had destroyed one of the most powerful military forces in the world and saved his kingdom, and with it, the fragile Christian communities that lay to the north.

Consequences and Historical Impact of the Battle of Tours and Poitiers

The consequences of the Battle of Tours and Poitiers were immediate and immense, but not quite so spectacular as later legend would have it. Charles Martel’s victory, as it happened, was not a last-minute reprieve granted by divine miracle. The plain of Tours may have been the Umayyad Caliphate’s farthest reach in the West, but it was far from being its limit. Martel’s forces were able to secure Frankish territory and contain the threat from the north of the Pyrenees, but small-scale Muslim raiding in the south of France would continue for several years.

The large-scale invasion of 732, though, was the high-water mark of Islamic expansion into Western Europe. For the Franks, it was a moment of deliverance, a sign that their armies, however divided and undisciplined they had once seemed, could stand against one of the most fearsome forces on the planet. The victory strengthened Martel’s authority over his rivals at home.

In addition to its military consequences, the Battle of Tours and Poitiers had considerable political significance. By checking the Umayyad advance, Martel had preserved the independence of the Christian kingdoms of Europe. Had he not, the fate of Iberia might have been the fate of Gaul, and a Muslim power would have ruled over much of Western Europe for centuries. Instead, the Frankish heartlands would become the seedbed of a new European power. The stability established by Martel’s reforms and victories would later be known as the Carolingian Empire, the rebirth of the political and cultural order of the West.

Martel used the prestige he gained in the years following Tours to further concentrate power into his own hands. No longer simply mayor of the palace, he ruled over all the Franks as if he were their king, with a united and disciplined military under his command. His political reforms integrated the growing influence of bishops and abbots into the government, in exchange for their support of his wars in defense of the Christian religion. The alliance between church and military power, the core of his new regime, would dominate European politics for centuries to come. Martel’s son, Pepin the Short, would eventually create the Carolingian dynasty for himself, and his grandson Charlemagne would transform that dynasty into an empire.

The symbolism of the Battle of Tours soon eclipsed its historical consequences. Medieval chroniclers, and more modern historians as well, have described it as the battle that “saved Europe”. Edward Gibbon memorably suggested that had Charles Martel been defeated at Tours, Western Europe would have adopted the Muslim faith. Such sentiments are more characteristic of nineteenth-century chauvinism than accurate historical analysis, but they are not entirely without merit. Whether in medieval works like the Royal Frankish Annals or later historiography, a sense of destiny has long attended this event. To many people, the Battle of Tours became not simply a Frankish victory but a pivotal point in the history of civilization itself.

In many ways the battle’s most lasting legacy was not the defense of Christendom but the definition of Europe. Charles Martel’s victory gave birth to the idea of Europe as something special, as something more than just the political order of a single geographical region. Through the Hammer of the Franks, the West was forged anew. Through his leadership, he would go on to define and defend this new civilization and provide the basis for a united Europe.

Myths, Memory, and Historical Debate

The memory of the Battle of Tours held a peculiar place in European consciousness. Chroniclers in Tours’s immediate aftermath framed it as the struggle that decided the fate of Christendom and, in fact, of the entire world. In the eighteenth century, Enlightenment historians like Edward Gibbon shared this perspective; as he put it, Charles Martel “had been defeated, perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford.” To Gibbon and others, the Battle of Tours was a world-historical clash, one that preserved Europe’s identity and ended the Islamic expansionist project once and for all.

In many ways, more recent scholarship has come to a different conclusion. Medieval chroniclers, for their part, tend to focus on the event’s symbolic significance, presenting it as a cosmic confrontation and a battle of religions. The battle itself, on the other hand, was a bit more prosaic; the Umayyad army may have numbered in the tens of thousands, but it was an invading raiding force rather than a full-scale invasion army, and the Caliphate’s attention focused primarily on North Africa and the Middle East rather than on northern Europe.

In many ways, Tours was less the culmination of history than a fundamental regional power struggle that just so happened to represent the practical limit of Islam’s expansion into Western Europe.

In some ways, this debate brings into question the religious elements of Tours as well; if most modern historians would be reluctant to describe the battle in quite the terms of Edward Gibbon’s apocalyptic fantasy, contemporary Frankish sources provide relatively little religious context for the conflict at all. It was more a struggle over territory, politics, and survival than it was a contest of beliefs and religions. Charles Martel fought not as a Crusader but as a statesman; in his day, centuries before the institutionalization of religious warfare, his efforts to drive the invaders back represented less a holy cause than a matter of national defense.

By the High Middle Ages, however, as the idea of religious warfare became more institutionalized, memory had recast the battle in explicitly theological terms and Charles Martel in sainthood; the Hammer of the Franks was remade as a Crusader-before-the-Crusades.

The remaking of memory was also a reimagining of Europe itself. The memory of the encounter became a foundational narrative for European identity; an army of Europe’s Franks stood fast against a Muslim force and turned the tide of history. Chroniclers and poets lionized the story and Charles Martel himself; the victorious Frankish commander, already a warlord with practical aims, became a saintly defender of Christendom, the Hammer of the Franks chosen by God to fulfill his will. For much of Europe, Charles Martel and the Battle of Tours’ memory became a source of both trans-European identity and a sense of unity, one that would shape generations in the High and Late Middle Ages to come.

In that regard, the more recent historiographical pushback against the more mystical, mythical memory of the battle and its participants has had little effect on the story’s actual place in European consciousness. Whether the Battle of Tours was truly the salvation of Europe or not, few would argue that its memory was not crucial to that process; regardless of his own politics, Charles Martel’s victory, and his victory alone, would come to define European memory of this moment in history. In memory and in myth, in actual history and in its later retelling, the Hammer of the Franks still strikes loudly through the ages.

The Legacy of Charles Martel after the Battle of Tours and Poitiers

The victory at Tours catapulted Charles Martel from a local warlord into one of history’s most significant figures. It not only secured the Frankish border but also his political future. Beyond the immediate military success, Martel’s larger significance lies in the reshaping of Europe. Martel was not just a warrior; he was a skilled political leader. He reformed the Frankish military, professionalizing it with a standing army, and introduced heavily armed cavalry, the forerunner of the medieval knight. To pay for these reforms, he expropriated church lands—an act that appalled the clergy but provided the necessary funds to build an effective defense. For Martel, the survival of Christendom was the end that justified all means.

Charles Martel’s personality and his image as a leader were as complex as his reforms. To future generations, he would be the “savior of Christendom”, the bold and virtuous leader who kept the barbarians at the gates. To his contemporaries, Martel was also an unscrupulous power player, a man who eliminated rivals, seized control by force, and blurred the lines between sainthood and ambition. The man who saved Europe from Islam also thumbed his nose at the church, diverting its riches to create his armies. This dichotomy—savior and pragmatist—is the early medieval ruler in a nutshell, a man forced to make moral compromises to survive.

The legacy of Martel would shape Europe for centuries. The political and military structures he put in place would become the foundations of the Carolingian Empire, which his son Pepin the Short and grandson Charlemagne would expand into the most tremendous power of the early Middle Ages. Without Martel’s centralization of power, the Carolingian Renaissance—a re-blooming of learning, culture, and governance in Europe—would have been unlikely. The intertwining of military might and religious authority would serve as a model for Christian kingship across Europe.

Martel’s victory and legacy also influenced ideas. The notion of a united Christendom, a European identity distinct from the Islamic world to the south and the pagan barbarians to the north, found fertile ground in the wake of his reign. Later generations would see him as a model of the faith’s defender, an ideal that would inspire medieval kings and crusaders alike. The Battle of Tours and Poitiers would come to represent the survival of an entire civilization and the belief that Europe was a culture worth fighting for.

In conclusion, Charles Martel’s legacy is one of change. The man who won at the Battle of Tours and Poitiers, through a combination of tactical genius, political acumen, and single-minded ambition, transformed a divided set of tribes into the embryo of medieval Europe. The Hammer of the Franks did not just smash his enemies—he shaped the anvil on which Europe was to be forged.