Combahee River Raid: The Civil War’s Boldest Rescue

The Combahee River Raid took place under the cover of predawn on June 2, 1863, when a fleet of Union gunboats moved up South Carolina’s tidal rivers. The ships were engaged in a fluid kind of military strike and a mission of liberation. Led by Colonel James Montgomery and guided by Harriet Tubman, the raid targeted Confederate rice plantations, supply depots, and bridges on the Combahee River. Fires were set, buildings were destroyed, and families of enslaved people came running from the riverbank. A Union officer reported that the spectacle had the appearance of “the whole river bank was alive” as enslaved people flocked from bondage within hours.

One notable thing about the Combahee River Raid, however, had as much to do with why it happened as with how. This was not just a military strike but an intentional act of rescue. One of its goals was to free as many enslaved people as possible, but the raid’s planners were also able to develop a plan based on intelligence received from enslaved people themselves. In both freeing over 700 men, women, and children and by damaging Confederate supplies and transportation infrastructure, the raid represented a turning point in Union warfare, showing how liberation could be both a moral and strategic goal.

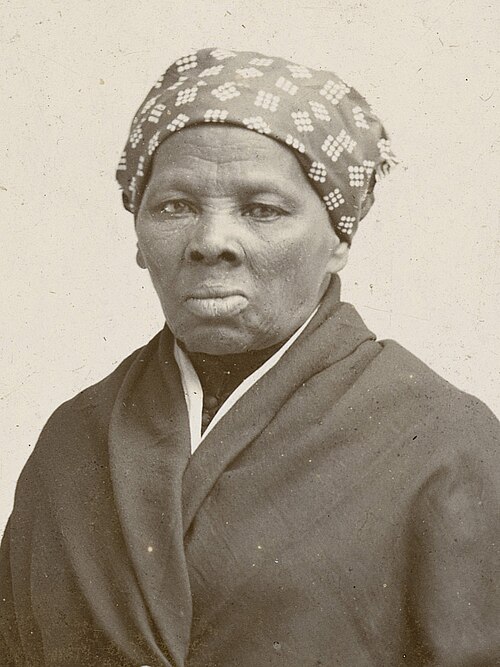

Harriet Tubman Enters the War

Long before she joined the Union cause, Harriet Tubman had been engaged in a personal war against slavery. She escaped as a slave from Maryland in 1849 and, in the following years, returned to the South again and again to help dozens of enslaved people escape via the Underground Railroad. When the Civil War began, Tubman saw in the conflict an opportunity that had been years in the making. As she recalled later, “I waited and prayed for this war,” confident that it would finally destroy slavery’s hold.

Tubman arrived in Union-occupied South Carolina in 1862. She quickly proved her worth to the army, and soon began work as a nurse, caring for sick and hungry soldiers and refugees in Union camps. She had a keen knowledge of herbal medicine and treated the diseases that were epidemic in the camps. These early duties brought her into regular contact with the Black refugees who were streaming into Union camps. They allowed her to listen, learn, and earn trust in communities that the Union Army barely understood.

But her most important role would be as a scout and intelligence gatherer. Tubman was able to organize networks of enslaved informants who could move through the plantations and along the riverbanks without raising suspicion, and who would report back on Confederate troop movements and locations of supplies. They also reported river mines that Confederates had put in place to try to disrupt Union operations. One Union officer marveled at how Tubman “seemed to know the river as if she had helped to dig it.” Her understanding of both the land and its people was unparalleled.

While many officers viewed intelligence as the purview of maps, Tubman recognized that enslaved communities possessed strategic knowledge. She knew the tides, the turning points along the narrow creeks, and the safe harbor points along the Combahee River. This information would come to shape Union planning in a way that lines on a map never could. Tubman’s lived experience became military intelligence, and in that sense, the bridge between the worlds of resistance and of war.

By the time of the Combahee River Raid, Tubman was no longer a behind-the-lines auxiliary but a key factor in Union success. Her leadership that day would show that emancipation, intelligence, and military force could function hand in hand.

The Strategic Importance of the Combahee River

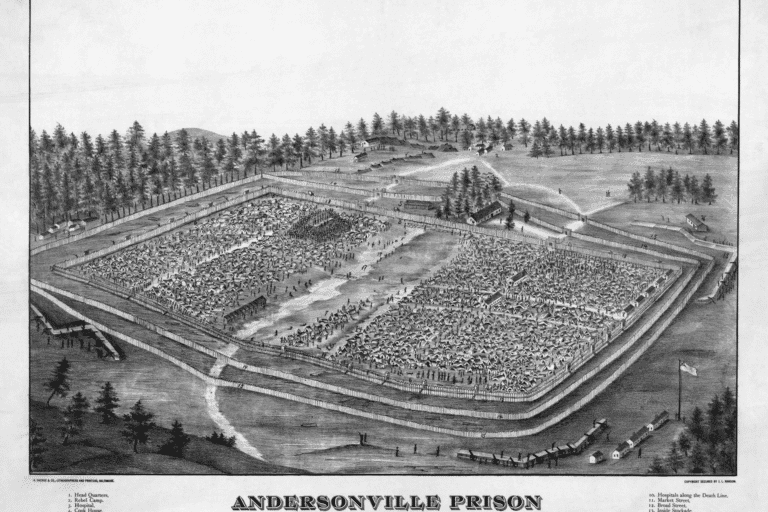

The Combahee River meandered through South Carolina’s lowcountry, a network of waterways leading inland plantations to the Atlantic coast. Treacherous with sluggish currents, marshy banks, and hidden creeks, it was challenging to patrol from the shore. The river served as a vital artery for the Confederacy, transporting foodstuffs and labor while remaining vulnerable to naval activity.

Plantations along the Combahee produced some of the region’s largest rice crops, worked by enslaved people and relying on the river to ship goods to market. These plantations fed and armed Confederate soldiers while generating the wealth necessary to continue waging war. A series of light fortifications, river mines, and widely dispersed pickets guarded its banks, designed to deter smaller raids rather than a concerted, multi-pronged attack supported by intelligence from enslaved populations.

Confederates stationed there believed the marshy conditions and narrow channels would protect the river from attack by a force large enough to attempt the operation. Those same conditions benefited Union Navy shallow-draft gunboats, able to move along these waterways, while larger ships remained in deeper ports. Its many bends and turns obscured the river from Confederate lookouts, giving the Union the element of surprise. Union commanders knew that dominance on the water translated to freedom of movement, communication, and supply.

Less understood but equally strategic was the human landscape. Enslaved men and women lived and labored along the river’s banks, free to travel as they pleased between plantations, farms, and the waterways. Their knowledge of tides, landings, and mine locations made this region uniquely vulnerable. This intelligence made the Combahee River a weakness rather than a natural line of defense.

The river, and those who used it, presented an opportunity. A single strike against the Confederacy could disrupt its logistics, morale, and enslaved labor systems simultaneously. The Combahee was not just a physical thoroughfare but a strategic fault line in the Confederacy. One well-planned raid was all it would take to sow military disruption and mass liberation in a matter of hours.

Planning the Combahee River Raid

The planning of the Combahee River Raid was deeply rooted in intelligence gathered outside the Union high command. For months prior, Harriet Tubman had been cultivating a network of trust among the enslaved individuals living along the Combahee River and on the surrounding plantations. Through songs, coded messages, and secret meetings, Tubman was able to gather critical information about Confederate mines along the riverbanks, which landings were most heavily guarded, and the timing of patrol shifts when they would be most vulnerable. This intelligence, acquired at significant personal risk, gave Union planners an advantage no topographical map could match.

Tubman collaborated closely with Union officer Colonel James Montgomery, a staunch abolitionist who shared her vision of taking direct action against the institution of slavery. Montgomery valued Tubman’s intelligence and engaged with her as an equal in the planning process, a significant gesture that acknowledged her as an operational partner rather than a mere informant. Together, they devised a strategy that would leverage speed, surprise, and Tubman’s local knowledge. Montgomery himself later stated that without Tubman’s guidance, they would have never been able to navigate the river safely.

A critical and deliberate decision in the planning was the inclusion of Black troops from the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, composed of formerly enslaved men. Their role was both a practical choice and a symbolic one. These soldiers had an intimate understanding of the landscape, knowledge of local dialects, and could directly communicate with the enslaved individuals they sought to liberate. Moreover, their active participation in the raid marked a significant shift in Union military strategy, moving towards the liberation of enslaved people as a tactical objective in the war.

The raid itself was meticulously designed as a coordinated naval operation, utilizing shallow-draft gunboats capable of navigating past Confederate defenses. Timing was of the essence; the boats would travel under the cover of night, guided by Tubman’s expertise in tides and river bends to reduce exposure to enemy fire. Speed was crucial; the longer the boats were in the area, the higher the risk of Confederate reinforcements arriving.

In every aspect, the plan reflected a level of preparation that went beyond mere tactical considerations, rooted in human intelligence and strategic thinking rather than just brute force. The objective was not only to destroy supplies and infrastructure but to actively dismantle a system of bondage. By combining Tubman’s clandestine network with Montgomery’s command acumen and the resolve of the Black soldiers, the Combahee River Raid was set to achieve something unprecedented in the Civil War.

The Night of the Raid (June 2, 1863)

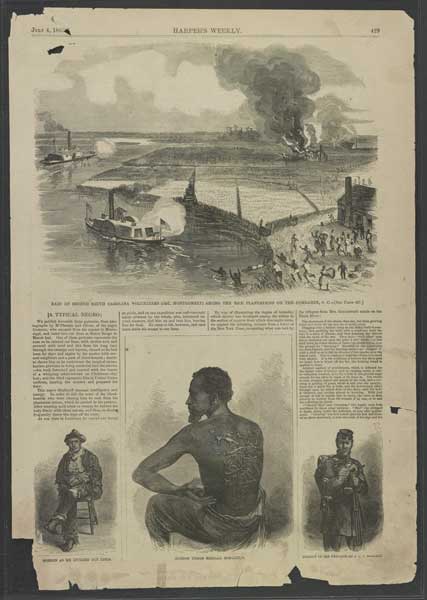

Gunboats slid into the Combahee River in the morning hours of June 2, 1863, with lights out and engines muffled. Confederate torpedoes (mines) were thought to be abundant on the river bottom. Still, Tubman’s intimate knowledge of the riverine landscape allowed the flotilla to slip past submerged hazards with relative ease. Soldiers stood by for a quick strike as the boats inched farther upriver, the mission’s planning and execution dependent on timing and silence.

As soon as they landed, Union troops moved quickly and quietly. Rice mills, storehouses, and supply depots that had fed Confederate armies were targeted first for torching, along with nearby plantations that enslaved people had long cultivated for their profits. Montgomery ordered other buildings burned, strictly those which had direct bearing on the Confederate war effort and had little impact on civilian housing and infrastructure. The raids were deliberate and effective.

Enslaved families emerged from cabins and fields as the flames took hold and word spread. They appeared on the riverbank in groups with children and meager possessions, at once fearful and hopeful. “Never saw such a sight,” Tubman later said. Hundreds of people gathered around the landings, uncertain but willing.

Union sailors and soldiers scrambled to get as many people on board as possible. Many were reticent, fearing it was a trap or Confederate forces were just around the corner, until Tubman finally appeared in plain sight and urged them on. She told those who listened that Confederate reinforcements would soon arrive, and by sunrise, the decks of the gunboats were teeming with men, women, and children who had been recently freed.

Confederate resistance took some time to materialize. Summer “sick season” illnesses of malaria, typhoid, and smallpox had forced commanders to retreat most of their troops from the Lowcountry’s rivers and swamps, where mosquitoes were bad, and flooding was worse, leaving behind only small detachments. The sentries hesitated to raise another false alarm without better confirmation, as there had been a recent incident. That hesitation gave the Union force time to escape.

Hours later, Confederate reinforcements began to arrive from McPhersonville, Pocotaligo, Green Pond, and Adams Run. Colonel Breeden rallied what troops he could and deployed a small artillery contingent, opening fire on the retreating Union force as they neared a narrow causeway. The threat was only temporary. Gunboat John Adams soon opened fire and blasted the causeway, forcing the Confederates into the woods. The Union flotilla escaped without losing a single soldier or sailor.

Liberation on a Massive Scale

In the space of one night, the Combahee River Raid would liberate more than 700 enslaved people. It was one of the largest mass liberations of the Civil War. As Union gunboats crept forward, plantation grounds emptied. Fields were left untilled, cabins deserted, and tools left behind. “They came in every imaginable condition,” a Union officer wrote of the escapees, “with children in arms, bundles in hand, or empty handed.” For many of the people on those plantations, this was the moment they had waited for their whole lives.

The riverbanks fell into a panicked tumult as the sound of cannon shells crisscrossed the marshes. Fear and prayer and urgency swirled around families as they crowded to narrow landings in the fog. Some stayed behind, too terrified of Confederate reprisals or too doubtful that freedom would really greet them on the other side. Others ran without looking back. Smoke from burning supply depots lit up the night sky, illuminating the flight towards freedom in harsh and flickering light.

In the midst of all this chaos, Harriet Tubman was everywhere. Trusted by enslaved communities along the Combahee River, she moved calmly through the crowds, coaxing them forward. “Come, one and all, don’t wait,” she reportedly called to them. To calm her nerves, she began singing spirituals she had used for years as coded messages. Her voice soothed the frightened, convincing them that these boats were Union and that escape was, in fact, possible.

By sunrise, whole communities were headed upriver aboard Union ships as free people. Many of the men would soon join the Union Army, turning their liberation into active resistance. The Combahee River Raid demonstrated that freedom could be won through careful planning, intelligence, and the force of arms. It redefined the purpose of Union warfare and, in one dramatic night, made clear what the war could mean for those who had known slavery.

Military and Political Impact

The Combahee River Raid was a near-flawless operation. Remarkably, not a single Union soldier or sailor was killed or wounded. The raid’s precision was the result of careful planning, good intelligence, and disciplined execution. In an era when minor skirmishes could still result in heavy casualties, the raid’s outcome was almost unheard of. This feat not only emboldened Tubman and her network but also reinforced faith in naval–land operations among Union commanders, who had already seen the benefits of amphibious raids on the Confederate coastline.

The material damage to the Confederacy was considerable. Rice mills, storehouses, bridges, and other infrastructure were destroyed, and plantations that provided food and export crops were burned. This destruction disrupted the Confederate supply lines and denied resources to the enemy. Many of the raids on plantations destroyed food supplies that had been set aside for Confederate troops, further tightening the screws on enemy logistics. Southern newspapers rued the raid’s success, as these targets provided more than just material support; they also offered financial resources to the Confederate war effort.

The freedom of more than 700 enslaved men, women, and children also dealt a significant economic and psychological blow to the Confederacy. Enslaved people were the backbone of Confederate wealth, and in coastal South Carolina, rice plantations were a cornerstone of that wealth. Tubman and her assistance in the removal of hundreds of enslaved people overnight crippled plantation operations and sowed fear and uncertainty among slaveholders. By targeting this labor force, the raid highlighted the vulnerability of slavery as an institution and an economic system during the Civil War, making it not just a moral issue but a military liability.

The Combahee River Raid’s success had significant political implications, especially in the North. It helped to shift public opinion and further defined the war’s aims, proving that emancipation and military objectives could be pursued hand in hand. The raid reinforced the logic of the Emancipation Proclamation by demonstrating that the liberation of enslaved people could simultaneously weaken the Confederacy and bolster the Union. Liberation went from being a symbolic act to a tactical one.

In addition to raising questions about the wisdom of slavery, the raid helped to change the way people thought about race and warfare. Tubman, who had been a slave herself, emerged from the raid as a planner, guide, and leader. Harriet Tubman’s role in this military operation proved that Black people could, and would, play significant and leading roles in the Union’s efforts. Her leadership in this endeavor would strengthen arguments for the expanded use of Black troops and intelligence operatives, as well as for their use in other capacities. The raid was a harbinger of a transformation in the Union’s understanding of who could fight and lead in the cause of freedom.

Why the Combahee River Raid Was Revolutionary

The Combahee River Raid was revolutionary for several reasons. First, it challenged assumptions about leadership. Tubman was not simply a helper or guide. She helped plan and direct a military operation. In a 19th-century army run by white men, a formerly enslaved Black woman asserted authority over planning and execution. As one Union officer later put it, Tubman displayed “rare intelligence and energy.” The raid made it impossible to ignore. Her leadership simultaneously upended military, racial, and gender hierarchies.

The Combahee River Raid was also the first major military operation planned in the United States using information collected directly from enslaved people. Tubman’s network reached across plantations and waterways, gathering exact details about river mines, troop locations, and escape networks. Enslaved informants became active agents of war, rather than passive victims. This was a dramatic shift in how intelligence was collected and in whose knowledge was valued.

The raid’s purpose was also revolutionary. Unlike previous operations aimed at territory or supplies, the Combahee River Raid had the liberation of people as its primary goal. Success was measured by the number of individuals freed and the amount of property destroyed. As one witness put it, the gunboats “went up to carry freedom.” The raid reframed military objectives in both moral and strategic terms.

The operation also reinforced the notion that emancipation weakened the Confederacy and strengthened the Union. Destroying plantations and enslaved labor disrupted Confederate supply lines and morale.

The raid showed that freedom itself could be a weapon of war. Enslavement, once considered a source of Southern strength, was now a vulnerability that could be exploited through organization and action.

Finally, the Combahee River Raid helped make the Civil War explicitly a war for emancipation. It showed that liberation could be achieved not just symbolically, but also through military force planned, executed, and defended. The raid did not represent freedom alone. It was an enactment of liberty. In that way, the Combahee River Raid helped redefine the meaning of victory and changed the way Americans thought about the war’s purpose.

Erasure and Rediscovery

Despite the success of the Combahee River Raid, traditional histories of the Civil War often downplayed or overlooked it. The focus was on white officers and big, bloodied battles. Raids like Tubman’s were seen as secondary missions or just trivia. Harriet Tubman was left as a guide or nurse, or disappeared altogether. One 19th-century military historian called the operation “incidental.” It shows just how powerfully ideas about race and leadership shaped what people thought was worth remembering.

Race and gender were crucial factors in this erasure. A military expedition planned and led in part by a black woman did not easily fit into heroic narratives. It challenged assumptions about who had the right to lead or to change the course of strategy. To put it plainly, Harriet Tubman’s authority challenged a belief in white supremacy. So the raid was silenced or left as an anecdote rather than a military operation. It was a deliberate erasure, not an accidental omission.

Race also played into how emancipation was remembered. Generations have been taught that freedom was a gift handed down from on high. A raid with enslaved intelligence networks at its heart undercut a myth of passivity. If the Combahee were fully understood, it would recognize enslaved people as wartime agents.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, some historians began to reassess these ideas. Scholars began examining military records, letters, and eyewitness accounts from new perspectives. They found that evidence for Tubman’s role was not just there, but quite clear. A report by an officer present was described as “invaluable.” Other documents show her as a planner and the person to decide the timing. It had become much harder to deny her the role of commander.

Assessing the raid with fresh eyes has put the Combahee River Raid back where it belongs in Civil War history. It is seen not just as a military success but also as a moment when race, gender, and war intersected in powerful ways. Tubman and the raid have changed how we understand leadership, intelligence, and the fight for freedom itself.

Legacy of the Boldest Rescue

The Combahee River Raid changed how the Union fought the remainder of the war. It proved that liberation raids could also damage Confederate supply lines and morale. After Combahee, the Union much more openly embraced military logic aimed at pressuring slavery and promoting emancipation—a logic that Sherman’s March to the Sea, which deliberately aimed to destroy the Southern economy to bring about faster collapse, would ultimately expand on a far grander scale. As one officer wrote, the raid demonstrated that freedom itself could be “a weapon more powerful than shot or shell.”

The raid also became an enduring symbol of self-liberation and resistance. More than 700 people chose to take flight in the face of fear and chaos, acting with urgency and purpose. They were not quietly rescued. They moved as families and communities, shaping the terms of their own escape. The raid made it clear that enslaved people were not passive actors in the struggle to win their freedom. They were its subjects, leading the way.

The Combahee River Raid matters today because it continues to challenge the traditional understanding of the Civil War. It reminds us that the liberation of enslaved people was often planned, fought for, and led by those directly affected. It stands as a testament to the power of courage, intelligence, and collective action to change the world.

![[Video] Phrase Origins: Mad as a Hatter](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Screenshot-2025-09-30-at-8.00.59-PM-768x512.jpg)

![[Video] Today in History: From the Pullman Strike to Labor Day](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Screenshot-2025-09-02-at-1.15.28-PM-768x512.jpg)