Elite Units of Antiquity: The Forces That Built and Defended Empires

From Greece to China, from Rome to Persia, empires relied on a few thousand elite troops to fight and win their wars. Elite Units of Antiquity: The Forces That Built and Defended Empires showcases the mightiest and most prestigious formations in the ancient world, from the fiercely disciplined Spartan hoplites to the Persian Immortals, whose “splendid armor and unbroken ranks” so impressed Greek historians. Standing for national pride and military prowess, these forces served as both the shock troops of antiquity and the object of the most fearsome reputations, and their discipline, training and courage often determined the fate of entire nations.

Elite Units of Antiquity also explores how these elite formations changed and defined the historical eras in which they were used. Whether it was Macedon’s Companion Cavalry sweeping across Asia or Rome’s legions conquering the ancient world, the armies we look at left an indelible mark on history. From tactics and discipline to battlefield innovation, we see how the legacies of these elite units endured long after their empires fell.

Elite Units of Antiquity

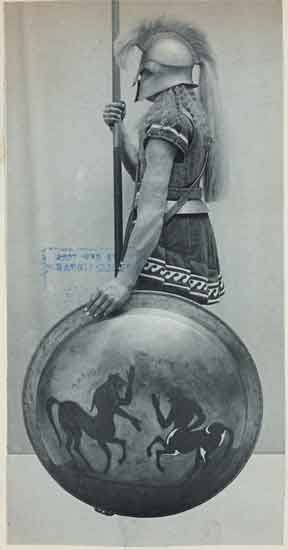

1. Spartan Hoplites (Greece)

The Spartan hoplites are often celebrated as some of the most formidable elite warriors in ancient history. Training from a young age, Spartan males were subjected to intense physical and mental conditioning. This preparation created soldiers of extraordinary endurance and fighting ability, as noted by writers of the time, who observed that Spartans were “accustomed to endure hardship and to conquer or die.”

One of the key elements of Spartan military prowess was the phalanx formation. In a phalanx, each hoplite soldier protected the one to his left with his shield, creating a wall of bronze and wood that could advance as a single unit. This tactic, combined with the rigorous discipline of the Spartan warriors, made their units nearly impenetrable. Xenophon, a Spartan historian, admired their discipline, stating that their ranks were “unevenly drawn, but they have sufficient staying power, like a rampart.”

The Spartans also held a deep-seated code of honor that forbade retreat without orders and stigmatized surrender. Cultural expectations of bravery and the societal pressure to return “with your shield or on it,” instilled by Spartan mothers, contributed to their fearsome reputation throughout Greece.

While Sparta did not often embark on extensive military campaigns, its hoplites were a critical force in its territorial defense and influence. The Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE stands as a testament to their military skills, where King Leonidas and his small army, including 300 Spartan hoplites, delayed the Persian forces. This defense, as Herodotus documented, provided time for Greek city-states to organize against the invasion.

The Spartans’ success was due not just to their physical training but also to their mental unity and the understanding of each hoplite’s role within the formation. The state of Sparta instilled in each warrior that personal glory was secondary to the collective strength of the polis.

Spartan hoplites have left a lasting impact on the history of warfare. Their methods, strategies, and values have been studied and emulated by generations of military thinkers. The legend of the Spartan warrior endures as a symbol of indomitable spirit and martial excellence long after their time has passed.

2. The Sacred Band of Thebes (Greece)

The Sacred Band of Thebes was one of the most extraordinary elite military units in the ancient world, comprising 300 soldiers organized into 150 pairs of devoted companions. The Sacred Band was established in the 4th century BCE on the principle that male lovers, fighting for each other, would exhibit unparalleled bravery and solidarity on the battlefield. Ancient sources such as Plutarch lauded their discipline, cohesion, and virtuous character, and it was even said that they were “invincible through love.”

The Sacred Band is most famous for their pivotal role at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE, where under the command of Theban general Epaminondas they innovatively defeated the once-invincible Spartan army. In a tactical maneuver, the Sacred Band was placed at the center of the Theban left, where they directly assaulted the renowned Spartan troops. As the Sacred Band and the rest of the Theban army advanced, their phalanx remained steady where others would have broken, crushing the Spartan line in a way that no Greek army had managed in centuries. The battle effectively ended Spartan hegemony and marked the rise of Thebes as a dominant power in Greece.

The effectiveness of the Sacred Band was the result not only of courage and skill but of comprehensive training and strategic deployment. Members of the Sacred Band were full-time soldiers, unlike other Greek hoplites, supported by the state and trained continuously throughout the year. They were often deployed at the most crucial points of the phalanx, enabling Theban commanders to employ more aggressive tactics in battle, assured that the Sacred Band could hold the line when needed.

It was their unique relationships that inspired the extraordinary bravery for which they were renowned. Ancient historians tell of the Band’s pairs standing side by side, encouraging each other to acts of heroism that few other soldiers could hope to match. The philosophy was elegantly straightforward: knowing that a comrade one loved was at their side would inspire a man to fight to his utmost, to never show cowardice, or to turn and flee. This morale boost gave the Sacred Band an edge over other ancient fighting units.

The Sacred Band’s final battle was at Chaeronea in 338 BCE, where they were defeated by the combined forces of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. Facing the aftermath, Plutarch tells us that Philip gazed upon the bodies of the fallen and, moved to tears, declared, “Perish any man who suspects that these men did or suffered anything unseemly.” Their legendary last stand further cemented their legacy.

The Sacred Band of Thebes continues to symbolize the power of devotion, unity, and elite martial prowess. Their stand at Leuctra and the role they played in shifting Greek power dynamics stand as a testament to the potential of an elite group of bonded fighters. They remain one of history’s most extraordinary examples of elite units and the might of companionship and courage in war.

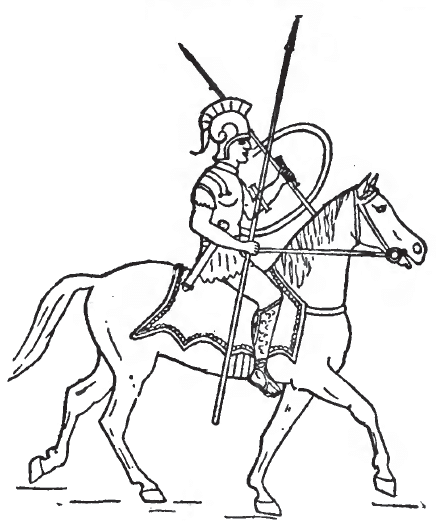

3. Macedonian Companion Cavalry (Alexander the Great)

The Macedonian Companion Cavalry served as the mounted arm of Alexander the Great’s military forces. This elite unit was made up of noble-born cavalrymen, who were trained from a young age in the ways of war. The Companions fought as heavy cavalry, charging into battle armed with long lances called xystons and wearing bronze armor for protection. Their role on the battlefield was to deliver a decisive charge at the most opportune moment, using speed, cohesion, and shock to break enemy lines. Ancient sources like Arrian frequently remark on their discipline and effectiveness in acting as Alexander’s arms and legs—fast, fearless, and relentless.

At its height under Alexander’s command, the Companion Cavalry was a highly effective force. Alexander personally led their wedge-shaped formations into battle, allowing them to concentrate their power and punch through enemy defenses. He employed the Companions to exploit gaps and weaknesses in the Persian lines at the Battle of Issus in 333 BCE and later at Gaugamela in 331 BCE, turning what could have been a stalemate into a route. The mobility of the cavalry allowed Alexander to perform rapid maneuvers that surprised and outflanked his enemies, earning him a reputation for “lightning-fast” conquest throughout Asia.

One of the primary strengths of the Companion Cavalry was the unity and loyalty of its members. As hetairoi or “companions” they served as cavalry and also as Alexander’s closest advisors and personal bodyguard. This engendered a level of trust and camaraderie that allowed the unit to perform complex, coordinated tactics on the battlefield. When Alexander ordered a charge, the Companions acted as one cohesive unit, their horses and lances driving forward in unstoppable momentum. Their bravery and combat effectiveness inspired the rest of the army and often broke the morale of enemy forces.

The composition of the Companion Cavalry also reflected Macedonian society at the time. The riders were often from wealthy families that could afford high-quality horses and armor, giving the corps an aristocratic air. This status came with its own set of expectations: they were routinely placed in the most dangerous positions on the battlefield and expected to fight with unparalleled courage. Historical accounts document how Alexander often put himself in the midst of the thickest fighting alongside his Companions, sharing in their danger and bolstering their loyalty.

The effectiveness of the Companion Cavalry had a lasting impact on military history. Their combination of speed, shock power, and professional training established a new standard for mounted warfare. Subsequent empires, from Rome to Persia, studied Macedonian tactics and incorporated aspects of their cavalry operations into their own military doctrines. The Companions exemplified how a well-trained, elite mounted unit could exert disproportionate influence on the outcome of battles, often achieving results much more quickly than traditional infantry alone.

By the time of Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, the Companion Cavalry had played a key role in creating an empire that stretched from Greece to India. Their battlefield precision and the bold leadership of their king set a standard for elite cavalry warfare that would influence future armies for centuries. Among the myriad forces of antiquity, few could match the Companions in their combination of speed, discipline, and devastating combat impact.

4. Macedonian Hypaspists (Greece/Macedon)

The Macedonian Hypaspists were the crucial middle-ground between the heavy Macedonian phalanx and the highly mobile Companion Cavalry. Versatile, elite, and well-trained, Hypaspists were selected from the army’s strongest and most disciplined soldiers. They were primarily used to protect the phalanx’s flanks, protecting enemy light troops or cavalry who might otherwise exploit the phalanx’s narrow defensive front. Ancient historians such as Arrian frequently emphasized the mobility of the Hypaspists. The phalanx could not maneuver easily, so, in this respect, the Hypaspists were often the infantry corps most crucial to Macedonian battlefield tactics.

The Hypaspists carried shorter spears and swords than phalanx pikemen, and they also used larger shields. They were also very mobile, trained to fight both on foot and on horseback. In effect, this made the Hypaspists something of a cross between traditional Greek-style hoplites and the more lightly armed peltasts, allowing them to fight in rough terrain or in confined spaces in a way that a Macedonian phalanx could not. Commanders used this enhanced mobility to a significant effect, often assigning Hypaspists to perform surprise attacks, rapid advances, and holding key positions during the course of a battle.

Alexander frequently used his Hypaspists to carry out his most audacious tactical maneuvers. At Gaugamela, the Hypaspists protected the king’s right flank while Alexander led the Companion Cavalry on a charge that smashed straight through the Persian lines. Their presence as a disciplined, cohesive fighting force ensured Alexander never had to fear a rout of the infantry wing at his side. Ancient historians and scholars credit the Hypaspists with Alexander’s ability to pull off many of his most dangerous battlefield gambits.

As with the Companion Cavalry, the Hypaspists were elite troops. Like many other aspects of his army, Alexander frequently selected his Hypaspists from noble or otherwise wealthy families. This meant that these troops had not just to meet, but often exceed the physical and tactical standards expected of regular Macedonian infantry. Their training focused on speed, stamina, and skill, and allowed them to march and fight at a rate of pace that many ancient units could not match. This made them well-suited to a variety of dangerous tasks, such as storming city walls in siege assaults or other special missions that required particular bravery or skill.

As Alexander expanded his empire, he began using the Hypaspists as a nucleus for a new royal elite guard. These units, known as the Argyraspids or “Silver Shields”, were famed for their exceptional discipline. Even in their later years, when the Silver Shields were a collection of older veterans, they remained among the most feared infantry units in the world. Their experience and fierce loyalty to the king allowed them to continue holding their own against even younger, fresher armies, a testament to elite training over many decades of warfare.

The Hypaspists’ legacy was one of mobility and flexibility. They were not quite as immovable as the Macedonian phalanx, nor as mobile as the Companion Cavalry. Still, their ability to serve as a bridge between these extremes became one of the great strengths of Macedonian military power. Their story also illustrates the importance of such flexible infantry in an era when the inflexibility of a rigid formation often decided the battle. As a result, the Hypaspists are an excellent example of how elite units can enhance an army’s strategic potential.

5. Roman Legions (Republic & Empire)

The Roman legions were the driving force behind Rome’s transformation from a city-state into an empire that spanned three continents. Compared to the citizen militias of earlier times, the legions were a true professional force. They were trained throughout the year and had to follow strict discipline. Rome could now deploy standing troops along its frontiers and react more flexibly to new challenges. Ancient authors like Polybius therefore described the legions as a well-organized and effective fighting force. “No army in the world,” he wrote, “is better adapted to meet all emergencies of war.”

The Roman legionary was equipped with a short sword (gladius), a spear (pilum), and a large rectangular shield (scutum). This equipment gave him a certain degree of flexibility and allowed him to fight at short and medium range. However, what set the Roman legions apart was the high level of cohesion among their ranks. Soldiers were trained for months, even years, to act together as a unit. They rotated the battle lines, kept formations under stress, and executed deliberate, coordinated strikes. These abilities made the legionaries effective against a wide range of foes, from the Greek phalanx to tribal warbands.

Another key innovation of the Roman military was its internal structure. The legion was divided into cohorts and centuries that could be maneuvered separately without losing tactical coherence. This provided Roman officers with greater flexibility in battle and gave them an edge against enemies with more rigid or loosely organized armies. Julius Caesar, for example, used these advantages to significant effect during the Gallic Wars, when disciplined Roman formations defeated much larger Gallic armies.

The Roman legions were also known for their ability to construct fortifications and other military engineering works with great speed and precision. Soldiers built roads, bridges, siege engines, and fortified marching camps. The engineering skills of the Roman legions not only expanded Rome’s strategic options but also increased its tactical flexibility. Fortified marching camps enabled the Roman army to move quickly into hostile territory while maintaining relatively stable supply lines. The marching camps were completed at the end of each day of march. The ability to build such elaborate camps even impressed Rome’s enemies, one of whom famously remarked that the legions were “an army of builders as much as an army of warriors.”

In response to new challenges, the legions evolved. During the Empire, Augustus and his successors reformed the military and standardized legionary training and pay, while later emperors recruited soldiers from across the Roman provinces. But despite these reforms, the Roman legions retained their core identity as highly disciplined, well-armed heavy infantry. As such, they were constantly refining their tactics when faced with new threats. This included the new enemy types posed by cavalry and horse archers in the East, as well as the Germanic tribes in the North. This adaptability is one reason why the legions became one of the longest-lasting military institutions in history.

The Roman legions have had a lasting influence on military organizations to this day. In fact, modern armies often emulate Roman ideas in organization, training, and logistical planning. The very idea of a standing professional army has its roots in Rome’s military. As a result, the legionnaire endures as a symbol of discipline and military excellence, an elite force whose legacy far exceeded the ancient world and helped define Western warfare.

6. Praetorian Guard (Rome)

Originating as the personal guard of Roman generals, the Praetorian Guard rose to become one of the most powerful and elite fighting forces in ancient history. Instituted by Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, as a military corps tasked with protecting the emperor and maintaining order in and around the capital, they quickly distinguished themselves from the legions stationed at the empire’s frontiers.

Praetorians were drawn from a select group of men, usually hailing from Italy instead of the provinces. They enjoyed higher pay, shorter service, and better living conditions. This exclusivity bred an elite culture within their ranks, and Praetorians were trained to be both bodyguards and shock troops in battle. Their armor was more ornate, and their helmets crested, a visual marker setting them apart from ordinary soldiers. Such accouterments symbolized their elite status and reinforced their role as the emperor’s guardians and the visible arms of imperial power.

The Praetorian Guard’s military prowess was not just ceremonial; it was proven on numerous occasions throughout Roman history. They were often deployed on campaign when emperors personally took the field, serving as an elite reserve force capable of decisively influencing battles. They played critical roles in quelling revolts and defending Rome’s political elite during periods of civil strife. However, their most significant advantage was their ability to respond swiftly and precisely to threats within the capital itself. The Praetorians were the only military force in Rome that could immediately mobilize to protect the emperor when enemies lurked inside the city walls. This ability was crucial, as threats could emerge from the city’s political factions as much as from external invaders.

The Guard’s position in the heart of Rome also gave them unprecedented political influence. They were more than just a military unit; they were kingmakers who could sway the course of Roman politics in a way no other force could. On several occasions, Praetorians deposed emperors, installed new ones, or extracted concessions and payments for their support. The most notorious example is in AD 41, when they effectively chose their next emperor by aiding Claudius’s ascension to the throne following Caligula’s assassination. Cassius Dio wrote that they “held in their hands the power of life and death over those who ruled.”

As the centuries passed, this political meddling became more and more corrupt. Praetorians became infamous for kingmaking, venality, and even auctioning off the imperial throne to the highest bidder (as occurred in AD 193 when they sold it to Didius Julianus). This degeneration of the Praetorian Guard eventually convinced Emperor Constantine the Great to disband them entirely in AD 312, after defeating them in battle. Their barracks, known as the Castra Praetoria, were destroyed, and the elite corps disbanded.

Nonetheless, the Praetorian Guard’s influence on Roman military tradition was indelible. Their unique blend of elite status, specialized training, and political influence made them unlike any other force in antiquity. The Praetorians were the strengths and the weaknesses of imperial Rome in microcosm: fearsome in battle, powerful in their influence, and ultimately undone by the authority they were meant to safeguard.

7. Immortals (Achaemenid Persia)

The Immortals were a unit within the ancient military structure of the Achaemenid Empire, known for their distinctive uniforms, battle tactics, and role as the Great King of Persia’s personal bodyguards. This elite force was primarily composed of 10,000 heavily armed infantrymen. Herodotus, the Greek historian, emphasized their unique structure by noting that the unit’s numbers were meticulously maintained; if a soldier was killed or incapacitated, he was immediately replaced to keep the unit’s number at 10,000. This practice fostered the legend of their immortality, both in their names and in their perceived invincibility.

Functionally, the Immortals served multiple roles in Persian military campaigns. As a standing army, they provided a reliable and disciplined force that could be deployed for both combat and protective duties. Their primary equipment included the now-iconic scale armor and wicker shields, as well as spears and short swords, which balanced practicality and ceremonial display. The Greeks and other contemporary observers also noted the luxurious aspects of their appearance, such as richly decorated garments and gold ornaments, underscoring their elite status. Despite this glamour, the Immortals were known for their strict discipline and professionalism in battle.

In military strategy, the Immortals served as shock troops and played a central role in direct engagements. They were particularly noted for their ability to maintain formation and apply continuous pressure rather than relying on single, explosive charges. This discipline allowed them to adapt to different combat scenarios, reinforcing lines as needed, flanking enemies, or protecting the king. Their psychological impact on both Persian troops, by enhancing morale, and on enemy forces, by intimidating with their disciplined ranks, was significant.

During key battles like the Battle of Thermopylae, the Immortals were at the forefront. Despite their equipment and training, they faced difficulties against the well-armored Greek hoplites in the confined pass. However, their role in these prolonged engagements was critical, with their persistent attacks highlighting Persian tenacity and tactical flexibility. Herodotus, in particular, notes the futility of their charges against the Greeks under disadvantageous conditions, further cementing their place as the stalwarts of Xerxes’ forces.

Symbolically, the Immortals represented the administrative power and unity of the Achaemenid Empire. Comprising members from various ethnic groups within the empire, they epitomized the Persian practice of integrating diverse cultures into a single military and administrative framework, maintaining their number as a constant symbol of Persian values of order and continuity. In governance and warfare, they were a potent symbol of the empire’s might and reach.

The legacy of the Immortals has endured for millennia. In later Persian dynasties and historical narratives, similar elite units were often compared to or inspired by the legendary Immortals. In popular culture, they remain among the most well-known and symbolically rich military formations of the ancient world. Their combination of martial skill, administrative symbolism, and enduring mystique around their immortality makes them a subject of fascination and respect.

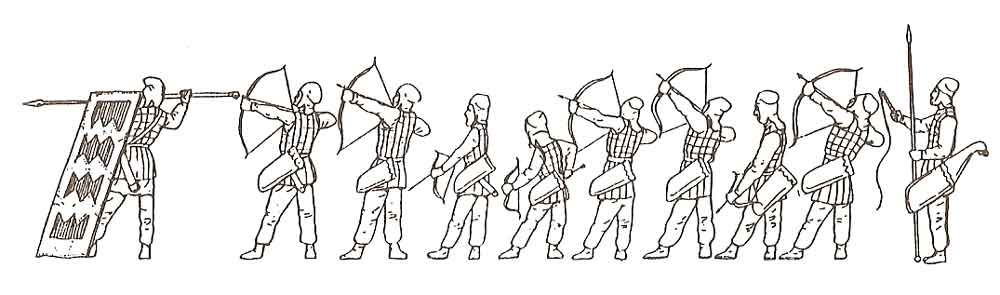

8. Persian Sparabara (Achaemenid Empire)

The Sparabara, or “shield-bearers,” were the primary shield-using infantry of the early Achaemenid Persian army. They were organized in ranks, usually carrying tall rectangular spara shields that formed a wall in front of them. Archers and spearmen could take cover behind the spara shields, making for a versatile and challenging force. The ancient Greeks wrote of the Persians and their layered, coordinated ranged attacks, and the Sparabara were the foundation for such tactics.

Persian shield bearers used lighter armor than the heavily plated Greek hoplites, and their wicker shields were typically lighter but reinforced for strength and durability. By holding a shield in a tight formation, Sparabara could keep moving and shift to different tactics, using their ability to move to make up for the lighter armor and shorter-range weaponry they were likely to face.

The Persians preferred a highly flexible approach to battlefield tactics, and the Sparabara units exemplified this strategy. Their shield wall was a defensive option, but they could also give way to absorb a charge or draw an enemy out to let cavalry strike, and these options were all part of the multi-layered, mobile tactics that set Persian armies apart from the Greeks in the eyes of some modern historians.

On the battlefield, Sparabara would usually be one of the first lines of engagement in battle. As the enemy approached, Persian archers behind the shield wall would open fire, harassing the opposing forces. If a fight broke up close enough, the shield-bearers would lay down their bows and fight with spears and shields in melee. Though the Sparabara were occasionally outnumbered or outmatched by heavily armored forces in defensive positions (particularly hoplites) in constricted terrain, their ability to hold off against enemy charges was one of their significant advantages on open battlefields.

Herodotus described the early Persian wars with a heavy focus on the incoordination and mismanagement among the different units of the Achaemenid army. The Sparabara themselves were not typically meant to act as standalone units in such a system, but instead were a first line to protect the various archers, cavalry, and elite units like the Immortals. Their function was to allow these other units to play to their strengths, namely long-range and highly mobile engagement tactics that defined so many of the Achaemenid successes across Asia.

Persian Sparabara are as much a symbol of the Achaemenid Empire’s approach to administration and cultural strength as they are a component of its battlefield tactics. Often recruited from other parts of the empire, Sparabara were one example of how the Persians could successfully field and move units across distances. Their shared training and standardized armor and shields are a sign of how heavily the Persians valued organization and a central, bureaucratic system of management. This, above all else, was the key to their long rule over a large portion of the known world.

The Achaemenid Immortals may have been the most famous units in the Persian armies, but the Sparabara were equally crucial to Persian success on the battlefield. Shield defense, coordination, missile support, and a flexible but disciplined formation system allowed the Achaemenid armies to control territory and expand from the Mediterranean to the Indus River. In many ways, the sparabara were the unsung foundation for the earliest Persian conquests, giving an opening for the grand strategy of the Achaemenid army to work behind them.

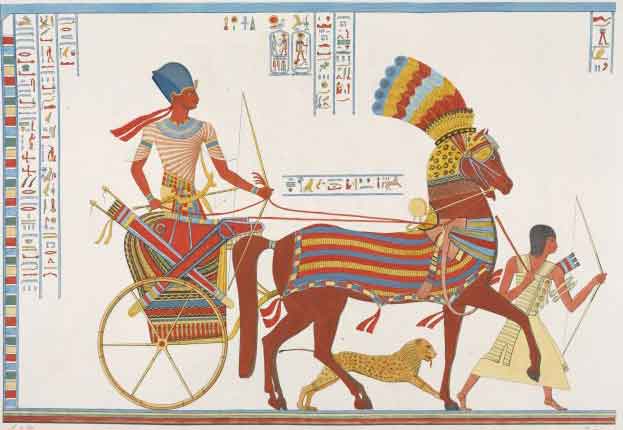

9. Egyptian Chariot Corps (New Kingdom Egypt)

The Egyptian Chariot Corps represents one of the most renowned elite military units in ancient history, achieving unmatched battlefield dominance from the 16th to the 11th century BCE. The introduction of the chariot to Egypt, following conflicts with the Hyksos, revolutionized warfare, offering both mobility and a commanding platform for archery and weapons. Integral to the chariot was its two-man crew, typically comprising a driver and an armed warrior. Highly skilled and trained from a young age, they mastered seamless coordination and precise shooting on the move. Pharaohs leading chariot corps into combat are frequently depicted in temple reliefs at Abu Simbel and Luxor, symbolizing their martial prowess and divine mandate.

The chariot corps emphasized speed, maneuverability, and archery over heavy armor. Egyptian chariots were lighter and faster than those of their contemporaries, enabling them to outmaneuver enemy formations and execute swift attacks. The warriors were armed with composite bows, designed for quick, accurate shooting. A well-drilled chariot unit could unleash a storm of arrows, decimating opponents before they had a chance to retaliate. This highly mobile and flexible warfare style made the Egyptian chariot an early form of skirmisher unit, particularly effective on open terrain and in large-scale battles.

One of the most detailed accounts of the chariot corps’ role comes from the Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE) between Ramses II and the Hittites. The battle, depicted in both poetic and monumental inscriptions, provides insight into its tactical importance. Ramses’ celebrated personal charge from his chariot is a prime example of how such units could be decisive. Despite the battle’s indecisive outcome, the Egyptian narrative emphasizes the charioteers’ discipline and valor as they repelled the more numerous and heavier Hittite chariots. Their ability to maintain formation and adapt to changing battle conditions became a hallmark of New Kingdom military strategy.

Training within the chariot corps was extensive and often exclusive to nobility or specialized recruits. Their education included archery from a moving platform, coordinated driving, and battlefield communication using horns and flags. The pharaoh himself was often depicted as an expert charioteer, underscoring the corps’ elite and symbolic status. Tomb paintings and surviving equipment, such as flexible wooden frames, leather bindings, and spoked wheels, highlight the craftsmanship and emphasis on speed and maneuverability.

Charioteers also occupied significant social and political positions. They often served as bodyguards, courtiers, or high-ranking officers within the royal administration. Their proximity to the pharaoh elevated them to a privileged warrior class. Their loyalty was crucial to the state’s stability, and some corps members were rewarded with lands or valuable goods for their service, integrating them into Egypt’s ruling elite.

In summary, the Egyptian Chariot Corps transformed the nature of warfare in the Bronze Age. Their combination of mobility, precision archery, and disciplined tactics set a new standard for elite military units. While the role of chariots declined in the Iron Age, the legacy of Egypt’s charioteers endured, serving as a testament to the power of military innovation and training to dominate the battlefield and sustain an empire’s might for centuries.

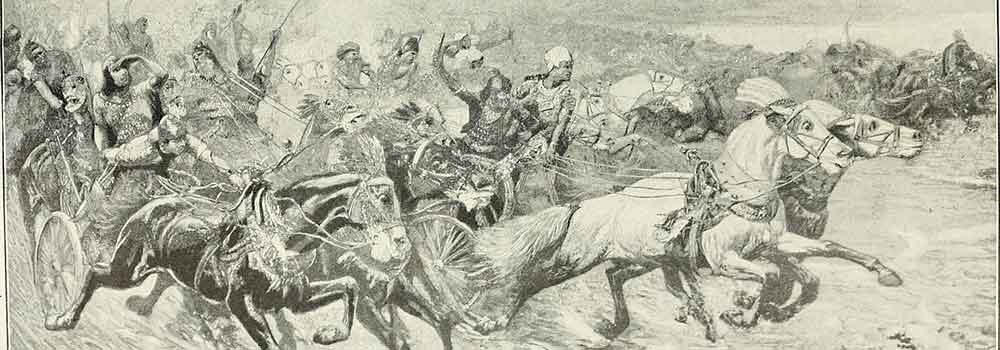

10. Heavy Chariot Warriors (Hittite)

Hittite heavy chariot warriors were considered one of the most effective shock forces of the Late Bronze Age. The Hittite heavy chariot was built to deliver a powerful impact on the battlefield, and they were especially good at breaking enemy lines through sheer momentum. Their chariots were often slower and heavier than the Egyptian light chariot, as they were designed to be more durable and carry additional troops.

The Hittite chariots usually had a three-man crew: a driver, a shield-bearer, and a spearman or archer. This allowed them to deal massive damage with coordinated charges at key points during a battle. Ancient sources, such as the Egyptian inscriptions of the Battle of Kadesh, record that the Hittite chariot forces advanced in a “storm of chariots” that could have wiped out entire Egyptian divisions.

The Hittite chariot design differed from the light Egyptian chariot in that the axle was reinforced and located in the center of the vehicle rather than at the rear. This design allowed it to carry more weight and more troops. The Hittite charioteers charged as part of larger, organized formations, which focused on creating openings in enemy lines with concentrated force. Infantry units would then capitalize on this advantage after the shock force of the chariots had shattered the enemy line. The heavy chariot of the Hittites was not only a technological advantage but also enabled a well-trained, disciplined force of warriors to execute complex maneuvers on the battlefield.

Hittite charioteers’ weapons made them even more effective as well. Warriors were equipped with long spears for use from the chariot and devastating composite bows that were able to pierce enemy armor. Shield-bearers on the chariot raised a large shield to protect the spearman or archer and the driver during the charge. The weapons and the chariot itself were used in coordination, allowing the crew to function as a single unit and switch between archery and close combat as needed.

The Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE) provides an excellent case study of the Hittite heavy chariot in action. According to Egyptian sources, thousands of Hittite chariots participated in a surprise attack on the Egyptian forces of Ramses II. The Hittites managed to scatter part of the Egyptian army, and the pharaoh was forced to put up a defensive position. The battle ended in a stalemate, but the battle serves as an example of the effectiveness of Hittite shock tactics.

Training for Hittite chariot warriors was likely extensive. Warriors had to be proficient in their individual roles as well as their part in coordinated maneuvers with other chariots. There is some evidence to suggest that many of these elite units were composed of members of noble or warrior families who passed military service down through the generations. In particular, the Hittite chariot corps was able to maintain formation over rougher terrain, which is in stark contrast to many other Bronze Age forces.

As the Late Bronze Age collapsed around 1200 BCE, the Hittite Empire and the heavy chariot corps faded from history. However, they left an impression in their enemies’ records, and their legacy as effective shock forces would live on as part of the evolution of elite units.

11. Assyrian Royal Guard (Neo-Assyrian Empire)

The Assyrian Royal Guard were the elite soldiers who protected the Neo-Assyrian kings. Equipped with bronze or iron helmets, scale armor, and tower shields, they served from the 9th to the 7th centuries BCE. The Royal Guard’s primary role was the personal protection of the king, and they were also a key component in the Assyrian military machine, serving as shock infantry.

Assyrian palace reliefs, particularly those from Nineveh and Nimrud, show the Royal Guard in full battle regalia, standing as a testament to the wealth and resources the Assyrian Empire invested in these troops. The presence of the Royal Guard symbolized the king’s power, and Assyrian chronicles often highlight the Guard’s proximity to the king in battle.

In the context of Assyrian warfare, the Royal Guard was part of a highly organized, professional army known for its siege warfare and use of infantry in heavy armor. Assyrian military might was underpinned by psychological warfare and the use of overwhelming force.

The Royal Guard, as elite shock infantry, was at the forefront of the Assyrian army’s ability to project power across the Near East. They were heavily involved in siege warfare, a key component of Assyrian military campaigns, and their role in close combat and fast-paced assaults was crucial. Historical records from Assyrian kings, such as Tiglath-Pileser III and Sennacherib, detail the exploits of the Royal Guard in suppressing uprisings and defeating foreign armies

In terms of equipment, the Royal Guard were among the most heavily armored soldiers of their time. Their scale armor provided significant defense, and they were equipped with conical helmets to protect against missile weapons. The Royal Guard also carried large rectangular shields, often requiring support from another soldier. As the king’s personal elite force, they were equipped with the highest-quality weapons available, including spears, swords, and bows. The combination of their armor, weapons, and military training enabled them to engage effectively in battle across various terrains, from the siege ramps of a walled city to the open battlefield.

Beyond their military function, the Royal Guard had a ceremonial and political role within the Assyrian state. They were tasked with guarding the royal palaces and escorting the king during significant state occasions. The display of the Royal Guard would have been a common sight throughout the empire, accompanying the king on his travels and serving as a potent symbol of Assyrian military strength. For foreign dignitaries and the subjugated peoples of the empire, an encounter with the Royal Guard would have been an immediate and tangible experience of the Assyrian Empire’s might. This served not only a martial purpose but also a political one, reinforcing the king’s absolute rule and the hierarchical structure of Assyrian society.

The visual documentation of the Assyrian Royal Guard is one of the most striking elements of their historical legacy. The Lachish reliefs, which depict the Assyrian conquest of the kingdom of Judah under King Sennacherib in 701 BCE, provide a powerful image of the Royal Guard in action. In these reliefs, Sennacherib is shown enthroned, flanked by his heavily armored guards. The contrast between the towering Assyrian soldiers and the captives at their feet is a clear depiction of the Assyrian military’s might and the role the Royal Guard played in it. These reliefs, like many aspects of Assyrian art, were designed to convey the absolute power of the king and the futility of resistance against the Assyrian Empire.

12. Carthaginian Sacred Band

The Carthaginian Sacred Band is notable for being one of the very few elite units composed of Carthaginian citizens. Carthage, known for rarely, if ever, employing a citizen-soldier army and instead recruiting mercenaries, fielded a corps of citizen-soldiers composed of professional Carthaginian aristocrats. Highly disciplined and cohesive, they would fight with great ferocity and defend their city to the last man. Written sources claim that the Sacred Band consisted of heavily armored spear infantry similar to Greek hoplites. This was a result of Carthage’s long cultural influence on the Greek world. If the Sacred Band was on the battlefield, it meant that Carthage was taking the threat seriously and was fielding its best soldiers.

The Sacred Band also had a reputation for exceptional discipline in battle. As the Sacred Band trained together often and fought alongside one another, they formed a very cohesive unit when faced with the enemy. This was in contrast to many of Carthage’s mercenary troops, such as the Numidian cavalry, Iberian infantry, and the Libyan spearmen, who were prone to flee during battle if the going got too harsh. Diodorus Siculus also claimed that, as Carthaginian citizens did not usually form up in fighting, it was a sign that the enemy posed a serious threat to the city of Carthage, to the point that it would send its most valued troops into battle.

The unit’s prowess is first explicitly attested at the Battle of Crimissus in 341 BCE, when they fiercely engaged the Syracusans led by Timoleon, refusing to yield or run despite their mercenaries fleeing. Many were killed where they stood by the Syracusan lines, and their position eventually gave way as the enemy pressed against them. The Sacred Band’s near-annihilation is often regarded as a good testament to their performance in the battle.

The Carthaginian Sacred Band was later reformed after their defeat in 341 BCE. They are still known to have been present in Carthaginian armies in the latter half of the fourth century and into the early third century BCE. They were often employed in Sicily during these years, as Carthage and the Greek city-states struggled for dominance in the region. The Sacred Band provided Carthaginian generals with a reliable infantry core that they could build their other allied and mercenary forces around. As a result, the Sacred Band often held the most critical positions in Carthaginian armies and was usually given the most important tasks during battles.

As with Carthaginian military history in general, records of the Sacred Band are somewhat scarce. It was highly unusual for Carthage to field citizen infantry units, as it would almost exclusively field mercenary forces in most of its campaigns. As a result, the Sacred Band was a strange aberration within the Carthaginian military and can also be seen as a statement on Carthage’s military culture during these years. Mercenaries were employed because they were an effective means of raising a large, flexible army at short notice; however, they were also a problematic reliance, as they were easily swayed to leave the battlefield during difficult times.

The Sacred Band, as a citizen unit, thus stood in direct contrast to this model and served as a source of internal unity, actively willing to participate in Carthaginian military operations. This also meant that the Carthaginian political elite were often in a position to share the risks that other states expected their citizens to take, and were at risk of falling in battle. This was, in part, the reason why they were held in such high regard among the Carthaginians.

The Sacred Band faded into obscurity as Carthage began to employ generals of renown, such as Hamilcar and Hannibal Barca, who used much more mixed and mobile forces. The Sacred Band last appears at the onset of the First Punic War in 264 BCE, and was likely either disbanded or replaced by other Carthaginian forces. The elite unit was, however, long remembered and revered as a source of great pride among the Carthaginians, and as a legacy which could be employed if need be. As a citizen unit composed of professional aristocrats, they were elite in training, equipment, and the written record.

13. Numidian Cavalry (North Africa)

Originating in the Berber kingdoms west of Carthage, the Numidian cavalry were among the most renowned light horsemen of antiquity. Known for their speed, mobility, and horsemanship, Numidians rode without saddles or bridles and were said to control their horses with only voice and pressure. Ancient authors like Livy and Polybius described them as so agile that they could “turn in an instant,” darting around slower, heavily armored cavalry and attacking where their opponents were most vulnerable. Their speed and light armor also allowed them to harass and outrun almost any enemy they faced.

Numidian cavalry tactics primarily involved harassment and mobility rather than head-on charges or extended melee. Armed mainly with javelins, they were used to skirmishing, outflanking, and wearing down their enemies. Numidians could draw infantry units into a chase and then quickly circle back for ambushes or to attack from the flank or rear. In open and flat terrain, where their maneuverability was at its most significant advantage, Numidian cavalry could prove particularly effective.

Roman commanders would eventually come to fear their hit-and-run capabilities significantly, as they could appear, scatter, and reform with surprising speed in the face of heavier troops. Numidian cavalry were inheritors of a long-established military tradition, developed by generations of horsemen of the desert and the steppe.

Numidian cavalry served an essential role in the Punic Wars, becoming among the most feared and effective cavalry units of the ancient world. Numidians fought on both the Carthaginian and Roman sides, but are best known for their role in Hannibal’s campaigns. They were often crucial in determining the outcomes of battles in which they were deployed, as their ability to harass and wear down enemy formations was unparalleled.

At the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE, Numidian cavalry played a key role in encircling the Roman army. By holding both flanks, the Numidians prevented the Roman cavalry from breaking away to support their infantry, thereby contributing to the Carthaginian victory. The historian Polybius attributes much of this success to the Numidian cavalry’s discipline and timing. The Numidians would be an essential part of Hannibal’s army early on in his campaign in Italy, where their ability to disrupt Roman formations and harass their troops proved invaluable.

Numidian cavalry also played a significant role in the Roman adaptation and use of cavalry forces. The Numidian King Masinissa would eventually break with Carthage and become an ally of Rome. In the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE, Masinissa’s Numidian cavalry rode for the Roman side. It would prove a decisive factor in Scipio Africanus’s victory over Hannibal, effectively ending the Second Punic War. Masinissa’s cavalry chased and scattered the Carthaginian cavalry before returning to attack Hannibal’s infantry in the rear.

After their success at Zama, Roman commanders realized the value of light cavalry, and cavalry became a more integral part of the Roman army. In general, Roman cavalry was more heavily-armored than its Numidian counterparts and was used more often in frontal attacks. However, light cavalry units inspired by the Numidians were also employed for harassment and skirmishing.

In addition to their effectiveness in battle, the Numidian cavalry was also remarkable for its horsemanship. Numidian cavalrymen were so in-tune with their mounts that they were said to be capable of astonishing maneuvers such as throwing javelins at full gallop, faking retreats to draw in pursuers, and then suddenly changing direction and doubling back to attack their pursuers. Another maneuver involved quickly splitting up to confuse enemies, then suddenly doubling back again in coordinated group formations.

Numidians are said to have required very little armor in battle, as much of their advantage over their opponents came from their speed and maneuverability rather than superior force. It was not uncommon for Numidian cavalry to neutralize opposing cavalry long before infantry from either side even engaged.

14. Samnite Warriors (Italy)

The Samnites are from central and southern Italy, and were among the fiercest enemies the early Romans encountered in their formative years. A tribal nation that inhabited the Apennine mountains in central Italy, the Samnites fought among themselves, with their neighbors, and with Rome in a series of protracted conflicts known as the Samnite Wars.

The terrain of their homeland dictated their approach to combat; steep mountains, narrow valleys, and rugged trails favored speed, flexibility, and familiarity with the land. This gave the Samnite warriors a significant edge over the more cumbersome Roman legions of the fourth and third centuries BCE. Livy described them as “hardy, warlike men.” The Samnite warriors were known for ambushes, swift strikes, and their ferocity once engaged.

Samnite troops were armed with oval scutum-style shields, short thrusting spears, and a curved sword called a sica. The armor varied by clan and personal wealth, but many Samnite warriors wore crested helmets and decorated breastplates, giving them an aggressive, fearsome appearance. Unlike Rome’s early hoplite-style phalanx, Samnite soldiers preferred more open and fluid formations, which allowed them to exploit the broken ground and rush around the battlefield. They were adept at ambushes and hit-and-run tactics, which were particularly effective in narrow mountain passes, where the strict Roman discipline was less useful and speed and mobility were more advantageous.

The protracted Samnite Wars, which lasted from 343 to 290 BCE, highlighted these strengths. Rome suffered several embarrassing defeats at the hands of the Samnites, perhaps the most famous being at the Battle of the Caudine Forks in 321 BCE. Samnite commander Gaius Pontius encircled two Roman legions and forced them to surrender. As a sign of total humiliation, the Romans were forced to pass “under the yoke.” This event had a profound effect on Roman society. It served as a stark reminder of how fragile their traditional methods could be against an enemy willing to resort to unorthodox tactics.

In response to the Samnite threat, the Romans implemented significant military reforms. The manipular legion – a more flexible system organized into smaller, more maneuverable units – was developed in part as a reaction to the Samnite way of war. This allowed the Romans to adapt to the uneven terrain and respond more quickly to the independent fighting style that made Samnite warriors so effective. In this way, the Samnites had an indirect influence on the army that would come to conquer the ancient world.

Even after their eventual defeat and incorporation into the Roman Republic, the Samnites remained fierce warriors. They were often employed as auxiliary troops in Roman armies, bringing their skills as mountain fighters to foreign campaigns. The Samnites would later take up arms against Rome during the Social War from 91 to 88 BCE, demonstrating their continued ability to fight effectively in defense of their autonomy. Samnite fighting ability and reputation made an impression on Roman military writers, who later listed them as an elite unit and among the fiercest tribal warriors of their time.

The legacy of Samnite warriors extends beyond their battlefield effectiveness to how they changed the Roman army. The Samnites forced the early Republic to rethink its military structure, strategy, and even its approach to engaging the enemy. In doing so, they had a hand in shaping the legionary system that would become one of the most effective fighting forces in history. Their influence on Roman military thinking would continue long after their own independence was lost, proving that even in defeat, some armies can change the world.

15. Han Dynasty Heavy Infantry (China)

The Han Dynasty’s heavy infantry formed the core of one of the most excellent military establishments of the ancient world. Highly trained, organized into formations, supplied by an extensive logistical infrastructure, and equipped with standardized weapons, they dominated the battlefield. They are known for their extensive use of crossbows—powerful mechanical weapons that could penetrate armor at range. According to Chinese historian Sima Qian, “the elite [infantry] are drilled soldiers and solid fighters. They are efficient at firing at will from a distance and then rushing forward to fight with spears, shields, and swords.”

The crossbow enabled Han infantry to penetrate enemy armor consistently, a feat not possible in most contemporary armies. Han crossbows had mechanical triggers and standardized bronze components that could be mass-produced for consistency. Because the spring mechanisms were standardized, they also had high draw weights, which made them easier for even average soldiers to use. Han infantry would shoot volleys from range, picking off cavalry and infantry. Bronze crossbows have been unearthed at sites such as the Terracotta Army, and they were mass-produced with high levels of standardization under direct imperial control.

Han infantry was highly effective in combined-arms warfare. In battle, they coordinated with cavalry, chariots, and lighter auxiliary units. They moved in tight formations, using the combined front presented by crossbow volleys and disciplined advancing lines to defeat their enemies. Units of Han heavy infantry would maneuver across the battlefield using flags, drums, and horns to communicate orders over the din of battle. They could quickly form and break formations, creating a defensive square, an aggressive spearhead formation, or a missile line, depending on the tactical situation. In this way, the Han would defeat nomadic raiders, break the power of rival Chinese states, and subdue formidable Central Asian kingdoms.

Han infantry were pivotal in expanding and defending the Han Empire. On long campaigns, Han infantry would advance north against the confederation of Xiongnu tribes under Emperor Wu. Securing the northern steppe allowed the opening of the Silk Road and the establishment of lasting peace and trade with powerful Central Asian kingdoms. Crossbow infantry were particularly useful against mounted archers, nomadic steppe warriors who had previously been difficult for Chinese armies to defeat with traditional warfare. Chinese commanders combined missile lines of crossbow infantry with mobile cavalry reserves, creating balanced military formations that could hold the field in long-lasting frontier warfare.

Infantrymen were drawn from conscription and received months of training in their trade. They were physically fit and skilled in their weapons. Manuals such as the Wu Yue Chunqiu and the Methods of the Sima provide details on the standards to which Han soldiers were held. Heavy infantry were drilled in holding formation in the chaos of combat, creating overlapping shield walls, and firing their crossbows in tight ranks and files. They were also required to dig and repair fortifications, build and destroy siege works, build roads, and perform other engineering tasks needed to support long-distance campaigns.

Han Dynasty heavy infantry would go on to influence Chinese military history for centuries. Their use of the crossbow, their standardized and disciplined formations, and their role in combined-arms units would all serve as foundations for later dynasties. Elite heavy infantry protected Han caravans, stood guard at imperial borders, expanded the frontiers of Chinese influence, and secured the position of one of the ancient world’s greatest empires—and changed the course of human history.

Conclusion

Ancient elite forces were more than military units; they were institutions that defined the identity, strength, and longevity of the empires they served. From the disciplined Spartan hoplite to the thundering Hittite chariot, from Rome’s meticulously organized legions to the swift Numidian horsemen, each unit reflected the values and ambitions of the culture it represented. Ancient authors—from Herodotus to Livy—chronicled these warriors with awe, marveling at their courage, training, and pivotal roles in the rise and fall of civilizations.

The legacy of these elite units endures not only in the annals of history but in the military traditions that followed. Many modern strategies, organizational structures, and elite forces draw inspiration from these ancient precursors. Though millennia have passed, the stories of these units continue to echo, reminding us how leadership, discipline, and innovation can shape the course of history.