Hawaiian Kingdom to American Territory: The Sugar Interests that Toppled a Queen

In the vibrant tapestry of Pacific history, the Hawaiian Kingdom is a testament to a rich cultural legacy and a pivotal era of geopolitical transformation. This once-sovereign nation, characterized by its unique traditions and independent monarchy, faced a seismic shift in the late 19th century as burgeoning American sugar interests began to cast a long shadow over the islands. This story delves into this critical juncture, unraveling the complex interplay of economics, politics, and power that led to the downfall of a monarchy and the eventual annexation of Hawaii by the United States.

The heart of this narrative is Queen Liliʻuokalani, the last reigning monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, whose steadfast determination to maintain her nation’s sovereignty collided with the expanding ambitions of American sugar planters and business interests. These sugar interests, seeking to maximize profit and minimize political obstacles, were at odds with the kingdom’s aspirations for self-rule.

The ensuing struggle, marked by diplomatic intrigue and covert maneuvers, culminated in the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. This historical episode has nuanced and often overlooked dimensions, shedding light on how the insatiable demand for sugar on the American mainland irrevocably altered Hawaii’s destiny.

The Kamehameha Dynasty’s Formation of the Hawaiian Kingdom

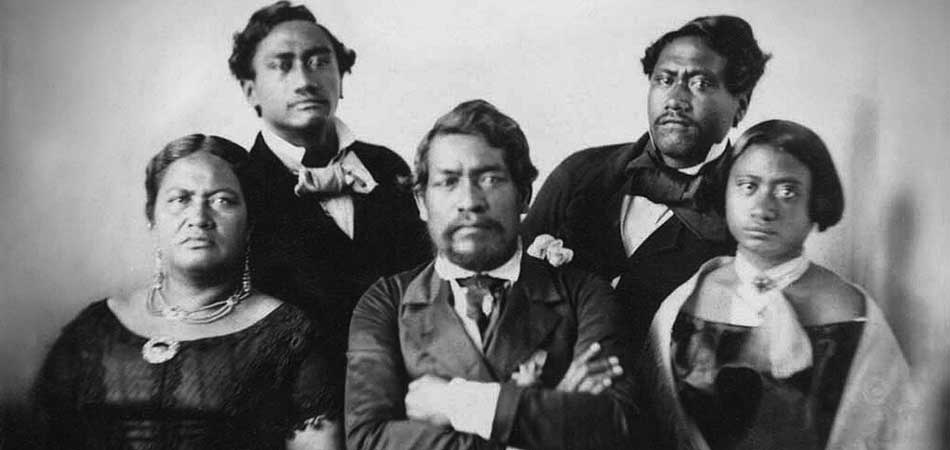

The Kamehameha Dynasty, rooted deeply in Polynesian heritage, was the pivotal force behind the Hawaiian Kingdom, guiding its evolution from a collection of independent chiefdoms to a unified sovereign state. This legacy began with Kamehameha I, a leader of great military skill and strategic insight, who, starting in 1795, embarked on a mission to consolidate the Hawaiian Islands under his rule.

His success in unifying these islands forged the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1810, establishing a dynasty that would carry on his vision until the death of Kamehameha V in 1872 and the subsequent short reign of King Lunalilo, ending in 1874. The dynasty, steeped in their Polynesian ancestors’ rich traditions and practices, not only united the islands but also fostered a unique cultural identity that persisted throughout their rule.

During the reign of Kamehameha III, the Hawaiian Kingdom reached new heights in diplomatic relations, particularly with the United States. On July 6, 1846, U.S. Secretary of State John C. Calhoun, on behalf of President Tyler, formally acknowledged the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This recognition marked a significant achievement for the Kamehameha Dynasty, affirming the Kingdom’s sovereignty on the international stage.

This era saw the Hawaiian Kingdom establish treaties with many of the world’s major powers and an extensive network of over ninety legations and consulates in various global ports and cities. These diplomatic efforts were a testament to the Kingdom’s desire to engage with the worldwide community while retaining its unique Polynesian heritage and sovereign identity.

However, the Kamehameha Dynasty’s pursuit to preserve and nurture the Hawaiian Kingdom’s autonomy and Polynesian cultural roots increasingly came under threat due to the growing influence of American sugar interests. The Hawaiian Islands’ strategic position and economic potential made them a target for American expansionist aspirations. As the sugar industry’s clout expanded, so did its interference in Hawaiian politics, signaling a challenging era for the Kingdom’s sovereignty.

Thus, the history of the Kamehameha Dynasty is a story of political unity and cultural pride and a narrative intertwined with the complexities of preserving indigenous sovereignty against the backdrop of escalating foreign economic interests.

The Sweet Rise of Sugar in the Hawaiian Kingdom

Sugar’s roots in the Hawaiian economy can be traced back to the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1778, marking the beginning of an era that would drastically transform the islands’ economic landscape. The establishment of the first permanent sugar plantation on Kauai in 1835 by William Hooper, who leased 980 acres of land from King Kamehameha III, was pivotal.

This venture marked the start of a sugar cultivation boom that, within three decades, would see plantations spread across four of the main Hawaiian islands. Sugar cultivation brought about a profound change in Hawaii’s economy, moving it from its traditional agrarian base to a plantation-centric system deeply intertwined with international markets and politics.

The growing influence of the sugar industry began to significantly shape the Hawaiian Kingdom’s governance, particularly with the rise of American-born plantation owners. These individuals, deeply invested in the lucrative sugar trade, sought more political representation, citing their substantial contributions to the kingdom’s economy and the royal family’s coffers.

This period saw a blend of missionary zeal and economic interests driving political change, putting pressure on the Hawaiian monarchy and chiefs for land tenure reforms. The 1839 Hawaiian Bill of Rights, or the 1839 Constitution of Hawaii, was a response by Kamehameha III and his chiefs to protect native land rights and lay the foundation for a free enterprise system.

However, following the 1843 occupation by George Paulet, Kamehameha III, under the influence of foreign advisors and missionaries like Gerrit P. Judd, implemented the Great Māhele, leading to significant land redistribution. In the 1850s, the Hawaiian Kingdom sought to reduce the heavy U.S. import tariffs on Hawaiian sugar through a proposed reciprocity policy, but this initiative faltered in the U.S. Senate.

The strategic importance of Hawaii, particularly to the United States, became increasingly evident in the 1870s. As early as 1873, a U.S. military commission, recognizing the significance of the Hawaiian Islands for the defense of the U.S. West Coast, recommended acquiring Ford Island in exchange for tax-free sugar importation. Major General John Schofield and Brevet Brigadier General Burton S. Alexander were dispatched to assess Hawaii’s defensive capabilities, with a keen interest in Pu’uloa, Pearl Harbor.

The potential sale of Pearl Harbor, proposed by Charles Reed Bishop, a foreigner with deep ties to the Hawaiian monarchy, became contentious. Despite Bishop’s influence, his wife, Bernice Pauahi Bishop, and many Hawaiians opposed the sale, fearing the loss of their sacred land. The reigning monarch, William Charles Lunalilo, initially entertained the negotiations but eventually abandoned them due to health issues and public disapproval, leading to his death in 1874 without an heir.

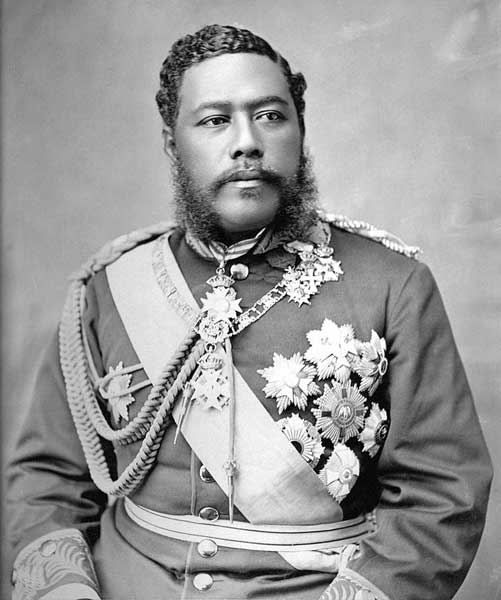

Following Lunalilo’s death, David Kalākaua was elected monarch by the legislature. He faced immense pressure from the U.S. to cede Pearl Harbor, a move he feared would lead to the annexation of the islands and a violation of Hawaiian traditions regarding land. To secure a better position, Kalākaua visited the United States in 1874-1875, resulting in the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, which traded Ford Island for the tax-free importation of sugar. This treaty led to an exponential increase in sugar production, expanding from 12,000 to 125,000 acres by 1891.

However, as the treaty neared its end, the U.S. showed little interest in renewal, setting the stage for further political and economic upheaval in the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Brewing Troubles: The 1887 Rebellion and the Bayonet Constitution

The year 1887 marked a turning point in the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom with the advent of the Rebellion of 1887 and the subsequent imposition of the Bayonet Constitution. The United States had begun leasing Pearl Harbor on January 20, 1887, a move that intensified political tensions within the Kingdom. In response, a group predominantly comprising non-Hawaiians, known as the Hawaiian Patriotic League, initiated the Rebellion of 1887.

This uprising culminated in drafting a new constitution on July 6, 1887, led by Lorrin Thurston, the Hawaiian Minister of the Interior. Thurston, leveraging the Hawaiian militia as a coercive force, compelled King Kalākaua to dismiss his cabinet and sign this new constitution under the threat of assassination. This constitution, which drastically reduced the monarch’s powers, came to be infamously known as the “Bayonet Constitution” due to the force and intimidation underpinning its creation.

The Bayonet Constitution fundamentally altered the political landscape of the Hawaiian Kingdom. It permitted the monarch to appoint cabinet ministers but stripped him of the authority to dismiss them without legislative approval. The changes extended to voting rights and eligibility for the House of Nobles. New property and income requirements effectively disenfranchised two-thirds of native Hawaiians and other ethnic groups who previously had the right to vote.

These voting requirements were tailored to benefit the white, foreign plantation owners, allowing them and other Europeans to retain citizenship of their home countries while voting and holding office in the Hawaiian Kingdom. In contrast, Asian immigrants were entirely excluded from acquiring citizenship or voting rights, revealing the racially and economically discriminatory nature of the new constitution.

Amidst these upheavals, under President Grover Cleveland and Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard, the United States monitored the situation with vested interest, primarily focused on protecting American commerce and nationals in Hawaii. Bayard’s directive to American Minister George W. Merrill emphasized supporting “the reign of law and respect for orderly government in Hawaii.” Thus, the Bayonet Constitution reshaped Hawaii’s internal political dynamics and played a pivotal role in the islands’ path toward American annexation, highlighting the complex interplay of local governance and foreign interests.

The Wilcox Rebellions of 1888 and 1889

The late 1880s in Hawaii were marked by the Wilcox Rebellions, a series of uprisings that profoundly shaped the political landscape of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The first rebellion in 1888 was ignited by a plot to overthrow King David Kalākaua and replace him with his sister, Princess Liliʻuokalani. This scheme was hatched following the Bayonet Constitution, which Kalākaua had been coerced into signing. Liliʻuokalani, who had just returned from Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, learned of her brother’s diminished authority and, feeling he was unfit to rule, conspired with Robert William Wilcox, a native Hawaiian officer and veteran of the Italian military. Their plan, however, was thwarted just before execution, leading to Wilcox’s brief exile.

The second rebellion, known as the Wilcox Rebellion of 1889, saw a more audacious attempt by Robert Wilcox, who returned to Hawaii with Princess Liliʻuokalani’s knowledge. Wilcox, along with his friend Robert N. Boyd and about 80 recruits from various ethnic backgrounds, formed the Liberal Patriotic Association. Their objective was to restore the monarch’s powers by forcing King Kalākaua to reinstate the Constitution of 1864.

On July 30, 1889, they launched their attack, donning red shirts inspired by Garibaldi’s Redshirts, and took control of key buildings in Honolulu. King Kalakaua was forewarned and stayed at Honuakaha, the private residence of Queen Kapiolani, helping thwart the rebels’ efforts. The ensuing battle was intense, with the Honolulu Rifles, led by Colonel Ashford, engaging the insurgents. Despite initial successes, Wilcox’s forces were eventually overpowered, and the rebellion was quelled.

The aftermath of the 1889 rebellion was a turning point for Hawaii. Wilcox lost several men, and many more were wounded, including Boyd. The conflict resulted in significant property damage, and the 2nd Battalion Hawaiian Volunteers was disbanded due to their neutral stance. Most rebels were imprisoned, but Wilcox was tried for treason and acquitted by an all-Hawaiian jury. In contrast, Lieutenant Albert Loomens, a Belgian member of the Liberal Patriotic Association, faced harsher consequences and was exiled. These rebellions, particularly their failure, paved the way for Liliʻuokalani’s ascension to the throne in 1891 and highlighted the growing tensions and divisions within the Hawaiian Kingdom, setting the stage for the dramatic political changes that soon followed.

The Tumultuous Reign of Queen Liliʻuokalani: Economic Crisis and Constitutional Struggle

Queen Liliʻuokalani’s ascension to the Hawaiian throne in 1891 came at a tumultuous time for the Hawaiian Kingdom. Following the death of her brother, King Kalākaua, in San Francisco in January 1891, Liliʻuokalani inherited a kingdom grappling with an economic crisis.

The McKinley Act, which had recently come into effect, severely impacted the Hawaiian sugar industry by removing the tariffs on sugar imports from other countries into the United States. This legislation negated the advantages that Hawaii had previously enjoyed under the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, putting significant financial strain on the kingdom’s economy. Liliʻuokalani proposed innovative but controversial solutions to mitigate this economic downturn, including a lottery system to raise government revenue and an opium licensing bill. However, these proposals were met with opposition from her ministers and close advisors, who feared the potential consequences of such measures.

Determined to restore the monarchy’s authority, Liliʻuokalani sought to repeal the 1887 Bayonet Constitution, which had significantly diminished the monarch’s power. Her proposed 1893 Constitution aimed to expand voting by relaxing property requirements and, crucially, to revoke the voting rights granted to non-citizen European and American residents. This move directly challenged the political influence of Hawaii’s robust Euro-American business community. The Queen’s determination to enact these changes was met with widespread support among the Hawaiian population. Her island tours on horseback to discuss her plans revealed a strong public backing, evidenced by a lengthy petition advocating for a new constitution. Despite this support, her cabinet hesitated, fully aware of the likely backlash from her powerful opponents.

The efforts of Queen Liliʻuokalani to strengthen the monarchy and address the challenges facing her kingdom were met with fierce resistance from the non-native subjects who held substantial economic and political power. The attempt to implement a new constitution that would reassert monarchical power over the legislature catalyzed the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

This overthrow was orchestrated by a group of conspirators, including United States nationals and other foreign residents, whose stated goals were the deposition of the Queen, the overthrow of the monarchy, and the annexation of Hawaii to the United States—this pivotal moment marked a significant turning point in Hawaiian history, as it laid the groundwork for the eventual loss of the kingdom’s sovereignty and its transition to American territory.

The 1893 Coup d’État and Overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy

The overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893 was a pivotal event orchestrated by influential figures, mainly from the American and European business communities residing in Hawaii. The coup was initiated by Lorrin Thurston, a newspaper publisher and former Minister of the Interior of Hawaiian descent, and was formally led by Henry E. Cooper, an American lawyer. These individuals, along with the Committee of Safety comprising U.S. and European citizens who were also subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom, leveraged their political connections and economic influence to bring about radical change. Their dissatisfaction stemmed mainly from the 1887 Bayonet Constitution and the subsequent attempts by Queen Liliʻuokalani to restore the monarchy’s authority, which threatened their economic interests and political influence.

The overthrow began on January 17, 1893, catalyzed by a confrontation between the Committee of Safety, backed by armed non-native men, and the existing Hawaiian government. The events were set in motion the previous day when Charles B. Wilson, the Kingdom’s Marshal, received intelligence of the planned overthrow and sought to arrest the Committee’s members.

However, the arrest warrants were denied due to their strong political ties, notably with U.S. Government Minister John L. Stevens, and fear of escalating the situation. The presence of the U.S. military, summoned by Stevens under the guise of protecting American lives and property, played a crucial role. On January 17th, Henry E. Cooper stood in front of ʻIolani Palace. He proclaimed the deposition of Queen Liliʻuokalani, abolishing the monarchy and establishing a Provisional Government headed by Sanford B. Dole.

This intervention by the United States and establishing the Provisional Government was met with international criticism, notably by President Grover Cleveland, who questioned the legitimacy of the U.S. military’s involvement. Despite the proclaimed intentions to protect American citizens, the troops were positioned strategically to influence the Hawaiian government and palace rather than safeguard American property. Under house arrest in the ʻIolani Palace, the Queen ultimately surrendered, prioritizing the safety of her subjects over resistance.

The Republic of Hawaii was declared in 1894 by the same individuals who had formed the provisional government, with Sanford Dole as its President, marking a significant step towards the eventual annexation of Hawaii by the United States. This coup d’état signified the end of the Hawaiian monarchy and highlighted the complex interplay of local politics, foreign interests, and economic motivations in shaping the islands’ destiny.

The Road to American Statehood: The Aftermath of Hawaii’s 1893 Coup

The 1893 coup d’état in Hawaii, leading to the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani, set in motion a series of events that would ultimately result in the islands’ transition from an independent monarchy to a state of the United States. The provisional government, established with the support of the Honolulu Rifles, a militia group, signified the beginning of the end for the Hawaiian Kingdom’s monarchy. Queen Liliʻuokalani’s poignant statement on January 17, 1893, underlines her forced abdication due to the overwhelming influence of the United States, represented by Minister John L. Stevens. This marked a significant turning point in Hawaiian history, paving the way for its eventual integration into the American fold.

Internationally, the coup elicited a varied response, with most countries quickly recognizing the new Provisional Government. President Grover Cleveland ordered an investigation into the events in the United States, which led to the Blount Report condemning the U.S.’s involvement. Although Cleveland initially sought to restore the monarchy, his efforts were hampered by the pro-annexationist Congress. The Native Hawaiian Study Commission later concluded that there was no obligation for reparations to Native Hawaiians, and it wasn’t until 1993 that the U.S. government formally apologized for its role in the overthrow. In Hawaii, resistance movements, such as the 1895 Wilcox rebellion, highlighted the ongoing opposition to the loss of sovereignty.

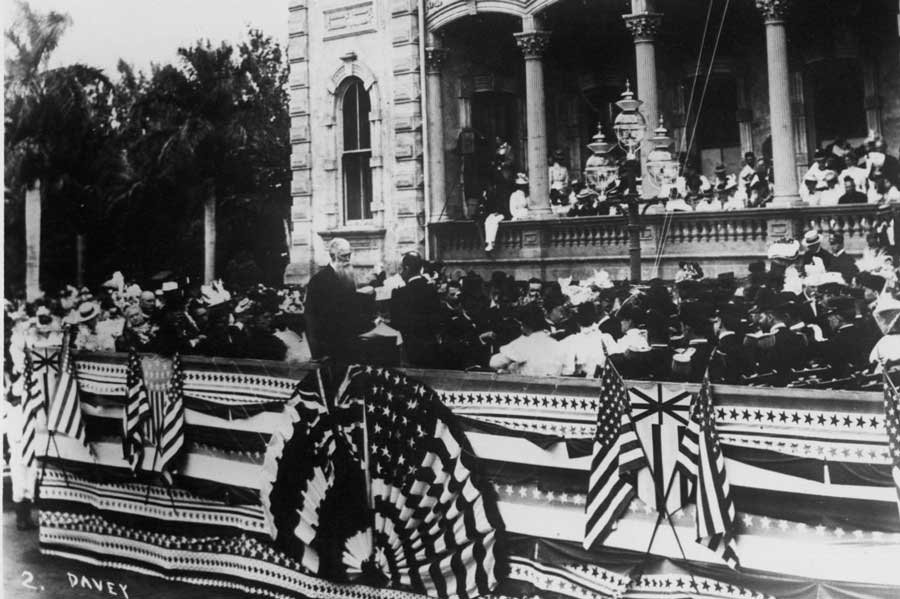

The annexation process reached its culmination under President William McKinley with the formal lowering of the Hawaiian flag in 1898, a moment met with widespread protest and mourning among Native Hawaiians. The transition to American territory was completed in 1900, establishing Hawaii as a U.S. territory with Sanford Dole as its first governor. This significant change laid the groundwork for Hawaii’s eventual statehood.

On August 21, 1959, Hawaii was admitted as the 50th state of the United States, marking the end of a long and complex journey from a sovereign kingdom to a state within the American Union. This transition period in Hawaiian history is a poignant reminder of the intricate interplay between local interests and global politics, encapsulating the challenges and changes faced by the Hawaiian people throughout their history.