Mao Zedong’s China: A Journey from Hope to Havoc

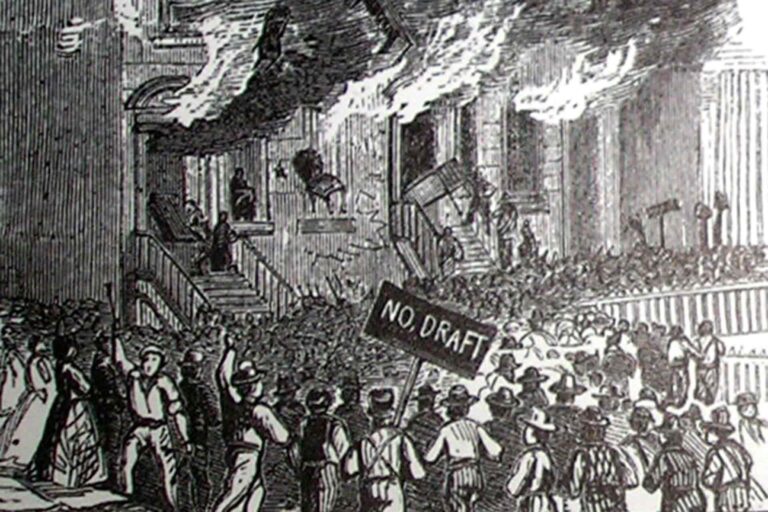

When Mao Zedong stood atop Tiananmen Gate and announced the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, citizens believed they had finally achieved a stable society ruled by justice. Few countries came into being on a promise so earnest, nor one that was heard by so many people. Land redistribution, reunification, and independence inspired hope for millions who had weathered years of invasion and civil war. “The Chinese people have stood up,” Mao famously proclaimed.

But the people’s newfound freedom was soon threatened by the policies of Mao’s revolution. Social campaigns intended to create equality and strengthen communist rule only inflicted fear, starvation, and purges on the population. This article will explore how the Chinese Revolution went from uplifting an entire nation to wreaking havoc on one of the world’s oldest civilizations.

Mao’s Rise to Power

When Mao Zedong rose to power, China was caught in one of the bloodiest and most chaotic periods of its history. After imperial rule collapsed in China, regional militias known as warlords fought each other and gained territory at the expense of a weak Republican government. Pressures from foreign imperialism added to the domestic turmoil. Mao came to power as an influential figure in the Chinese Communist Party, advocating for revolutionary change that diverged from traditional Marxist thought by focusing on mobilizing peasants in the countryside. The majority of China’s citizens were peasants, so Mao focused his party’s cause on them.

Mao’s ascent to power began with his conflict against Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist government. When fighting between the Nationalists and the Communists resumed after the Second Sino-Japanese War, Mao’s goal was to outlast the Nationalist government while gaining legitimacy as the only alternative. Chiang controlled the cities and had international support, while Mao was actively being pursued by Nationalist armies. They destroyed much of Mao’s army in 1934, forcing the surviving members to embark on the legendary Long March to evade being slaughtered. Mao Zedong maintained an image of order and power despite his circumstances, which gave his followers something to believe in and personified endurance as a virtue.

Japan inflicted significant damage to the Nationalists during their invasion of China. The Nationalists were busy warding off the Japanese invasion, allowing Mao to grow his forces in the territories behind enemy lines. Mao’s armies also began to accrue support by reorganizing peasant resistance against the Japanese. They redistributed land from rural landlords and kept their soldiers in check to prevent them from appropriating peasants’ labor. Mao said that the party withstood persecution because “The guerrilla must move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea”. The Second Sino-Japanese War enabled the Communists to gain valuable time, credibility, and popular support.

Peasant support for Mao Zedong is one of the most important factors in his ascent. Communist ideas spread quickly through villages that had been suppressed by landlords. Disenfranchised peasants were inspired by Communist cadres who empowered them and made them feel worthy. Villagers were taught how to read and write by the cadres while also being organized to work on major party initiatives. Mao framed the conversation of revolution around moralistic ideals of justice rather than foreign ideology. By convincing peasants that their survival was linked to his land reform, Mao inspired devotion that could not be coerced.

Civil war erupted once more between the Communists and Nationalists after Japan’s surrender in World War II. Though the Nationalists held the cities and still had international support, their government had been severely weakened by corruption, inflation, and constant war. The Communist armies had been engaged in guerrilla warfare throughout the conflict and had quickly seized major territory. Mao stressed the importance of patience and strategic encirclement. Cities were eventually allowed to fall to the Nationalists after the Communists gained control of the countryside. Avoiding direct confrontation with the Nationalists’ larger armies prolonged the war and eroded the morale of Nationalist troops and politicians.

By 1949, Communist victory was all but assured. Nationalist troops began to surrender and defect to the Communists by the thousands. In an effort to retain what remained of his regime, Chiang Kai-shek and the remnants of his government fled to Taiwan. On October 1, Mao Zedong stood atop the gate of the Forbidden City and announced the victory of Communism and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. He famously proclaimed, “The Chinese people have stood up.”

Early Reforms and Consolidation of Power

As Mao Zedong rose to power, he promised to bring change to China after decades of conflict and foreign humiliation. Reform began soon after the Communists assumed control in the early 1950s. The party labeled the reforms morally motivated, designed to eliminate feudal corruption and uplift the common man. Life under the Guomindang had been chaotic, and many citizens welcomed public order and certainty. The new government initially had wide support.

Millions of acres were confiscated from landlords and given to poor peasants. Much of the land was taken during public struggle sessions. To peasants who had farmed under the weight of rent and debt for generations, ownership was transformative. Combined with rhetoric that landlords were “parasites”, violence against them was cast as corrective justice. Hundreds of thousands of landlords were killed.

Parallel campaigns were carried out against so-called “counterrevolutionaries”. Former officials of the Nationalist government, suspected collaborators, religious figures, and local elites were targeted. Trials were often held in public and were designed to frighten people into compliance. Mao stated, “revolution is not a dinner party”, and that minorities who opposed the party would be ruthlessly repressed.

Other political dissent was not tolerated. All other political parties were ordered to disband or be absorbed by the Communist Party. Education and media were brought under party control. Intellectuals were pressed into service to help with the nation’s development. Debate and public discourse were allowed, but only when they served party objectives. As a result, acceptable forms of speech grew narrower.

Campaigns such as the Three-Anti and Five-Anti movements sought to bring cities and private businesses under party control. Corruption, tax evasion, and “bourgeois tendencies” were prosecuted, sometimes indiscriminately. Many businessmen and merchants were forced to commit suicide, while others went to prison or were heavily fined. These campaigns broke the last of China’s economic independence.

In a surprising move, Mao Zedong initiated the Hundred Flowers Campaign in 1956. Citizens were encouraged to voice their criticisms of the government, and “let a hundred flowers bloom.” However, when criticism of the party grew more widespread than Mao had hoped, he launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign to root out these “counterrevolutionaries”. Millions were sent to labor camps for their opposition. Mao had effectively shut down free speech.

By the mid-1950s, Mao Zedong had complete control over the nation’s land, politics, and thought. The early years of Communist rule in China seemed to promise stability and material improvements for citizens. However, they also instilled fear and quashed political dissent. Mao had ensured that political power would face little opposition moving forward.

The Great Leap Forward: Ideology Over Reality

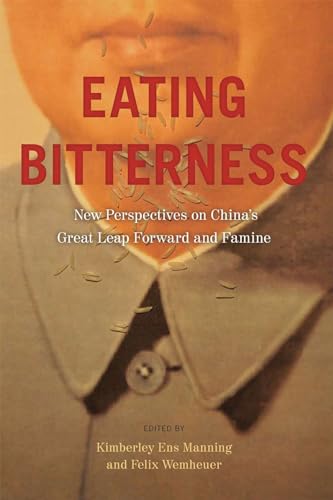

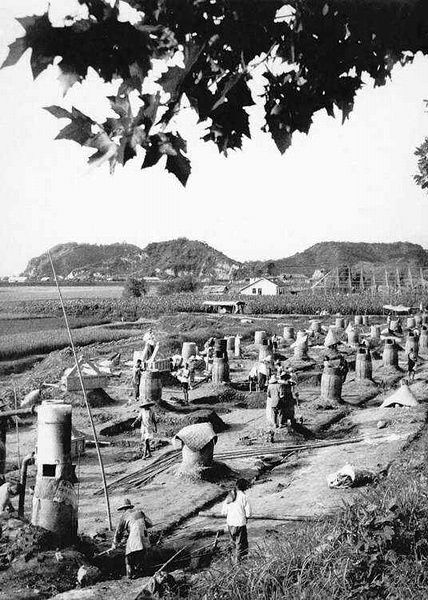

The Great Leap Forward was announced in 1958 with Mao Zedong confidently predicting that China would catch up with advanced industrial economies in the near future. Mao held that revolutionary fervor could replace expertise and that the people could meet physical limits through sheer willpower. The Great Leap Forward was sold to the public as both a patriotic movement towards socialism and communism, as well as requiring great sacrifice, speed, and unquestioned dedication from its participants.

Peasants were put into enormous people’s communes where private life ceased to exist. Family units were disbanded as everyone lived and worked together, with their days planned out in near military fashion. Officials were tasked with demonstrating perpetual growth and ideological correctness. There was no margin for error, as regional officials quickly learned that it was better to lie about failure than face punishment. Reality became substituted with political pressures.

People were ordered to melt scrap metal in backyard steel furnaces to boost production numbers. In their zeal to meet impossible production quotas, Chinese citizens melted down everything from pots and pans to farm equipment, and the metal created was often unusable due to its low quality and often brittle nature. Millions of man-hours were diverted in order to meet these quotas that existed only on paper.

Reporting became falsified at every level as regional officials reported impossible production feats to their superiors, who were just as afraid to tell their bosses that the numbers didn’t add up. As historian Yang Jisheng described it, “lies became heaped upon lies. Lie on top of lie, until the truth was buried.” Policies were created based on these falsehoods.

In less than a year, mass fatigue, oppression, and systemic violence had killed millions of people in what was, for China, peacetime. People weren’t allowed to move about freely, and suffering was largely hidden from the world. What was happening was concealed by the government and those in power.

Mao Zedong refused to accept any wrongdoing and instead blamed natural disasters and the incompetence of local officials. He would only tolerate minor adjustments to the Great Leap Forward if his peers pushed hard enough. China never accepted responsibility for the man-made atrocity.

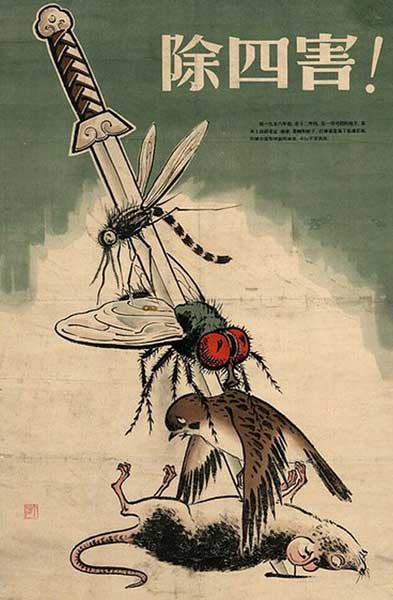

Four Pests Campaign: Ecology Misunderstood

The Four Pests campaign began in the spring of 1958, one of the first of the Great Leap Forward’s campaigns. The campaign ordered the extermination of rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows on a widespread scale. It was marketed as revolutionizing hygiene through science. Mao Zedong had laid the groundwork for policy statements earlier, claiming that by showing willpower, society could change nature. Targets were varied and often dependent on quotas issued by higher officials. As a result, the Four Pests campaign quickly turned into a nationwide competition of loyalty and obedience.

Government officials also claimed that mosquitoes spread malaria, rats caused plague, and flies were creatures of filth. Sparrows were targeted for eating grain and seed, particularly the Eurasian tree sparrow. By February 1958, the campaign was officially underway. Millions took to their roofs and drums, keeping records of every kill. Once again, the campaign had become political theater.

The campaign against sparrows was especially catastrophic. People worked day and night to keep sparrows in the air until they died of exhaustion. National news outlets reported that over one billion birds had been killed by the end of 1958. The People’s Daily wrote that streets were now cleaner, people were healthier, and that nature itself bowed down to the socialist society. Sparrows were killed en masse, and because of their disappearance, so too was nature’s understanding of insect control.

With the bird population decimated by humans, locusts and other insect populations grew wildly out of control. Massive amounts of sparrows were killed, and without them, there was no natural predator to eat the crops. Fields already ravaged by other policy changes suffered. Millions were dying from policy-induced problems, yet what was framed as scientific analysis of nature paid little regard to ecological relationships.

By 1960, sparrows had been removed from the Four Pests list, replaced with bed bugs. The campaign had slowed as the Great Leap Forward unraveled. Corruption, economic collapse, and administrative inefficiency caused many officials to stop enforcing the campaign. After 1961, it mostly ceased to exist.

Ecological damage from the campaign helped contribute to the Great Chinese Famine, which lasted from 1959 to 1961. Deaths by starvation are estimated by historians to be in the tens of millions. Historians commonly estimate that between 15 and 55 million people were killed. Exact numbers are hard to come by, but the impact of human life was enormous. Sparrows were even imported from the Soviet Union to help repopulate the species. History still remembers the disastrous Four Pests campaign as a lesson on what can happen when science and constructive criticism are ignored.

The Culture of Fear and Silence

Fear was a mainstay of Mao’s leadership almost from the beginning. Officials were told that they must have absolute faith that their policies would succeed, regardless of the facts before them. Failing to report the full completion of a goal was considered dishonest reporting, rather than an act of political subversion. Those who admitted failure risked being stripped of rank, publicly humiliated, thrown in jail, or even executed if they questioned party mandates or failed to meet stated goals. The only thing that mattered was obedience.

The result was that telling the truth meant you suffered. Officials who went to higher levels with accurate reports—say about food shortages in the coming year, or a breakdown in the party bureaucracy—were labelled as lacking a “revolutionary spirit.” Many such people were singled out as “rightists” or even counterrevolutionaries. “To tell the truth,” one former member said later, “was to invite disaster.”

Chinese citizens lived in a constant state of alternate reality, shaped by propaganda. Local newspapers, wall posters, and radio stations trumpeted great success and great accomplishments. The People’s Daily stopped reflecting Chinese life and became a window into the party’s fantasies. Without any concrete information to go on, Mao Zedong and his bureaucrats simply repeated party slogans rather than investigate conditions. If everything sounded fine from on high, it must be fine.

Rumors and exaggeration became standard practice in China. Local leaders padded their numbers to please those above them and avoid disgrace. But the more things seemed to be going well on paper, the less anyone paid attention to what was actually being reported. Policies could not be blamed for causing problems, because, by all official accounts, there were none. The danger was that as lies grew to satisfy party expectations, telling the truth became riskier.

Fear even spread to ordinary Chinese citizens who learned not to speak freely, even around their families. People’s words could be used against them, so citizens learned not to complain—or even to make false promises to their children—lest someone overhear them.

Neighbors informed on neighbors. Many people simply learned not to talk at all. While this silence may have kept people from coming to grief by speaking out, it also prevented them from banding together to help one another.

It didn’t stop disasters from happening, of course. Famines continued to occur because officials refused to believe that failing policies might be the cause. When confronted with early signs of collapse, Maoist bureaucrats blamed natural forces, or “rightist conservatives” who were doom-and-gloomers. Mao Zedong himself issued warnings against “rightist conservatism.” At a minimum, policies that were killing people were continued for years. By the time that they were reversed, a significant percentage of the population had already died.

The Cultural Revolution: Revolution Turned Inward

By the mid-1960s, Mao Zedong began to feel that both his power and the revolution itself were threatened. The Communist Party leaders were beginning to reinstate some measure of order and expertise after the disasters of the earlier years. Mao saw this as betrayal. In 1966, he launched a call to “continue the revolution.” He warned that China’s enemies were behind him in the government, subtly undermining the socialist program. He proclaimed that class struggle would now be between “ideas, and between habits, and between people.”

Mao had found his ammunition among China’s youth. Millions of students joined Red Guard units, given free rein to attack teachers, party officials, and even their own parents if necessary. They traveled through cities and villages across the land, armed with quotations from Mao. Violence became a virtue. Red Guard pamphlets put it simply: “Rebellion is justified.” Schools shut down the classroom became a battleground.

Across China, ancient temples, libraries, paintings, and monuments were burned. They were part of the “Four olds” of Chinese tradition that Mao Zedong was determined to root out. Schools and universities closed their doors. Intellectuals were humiliated, driven out, or killed. Learning of any kind was seen as suspect by the Red Guards. Universities would remain shuttered for years, leaving an entire generation without education.

Parents hung posters of Mao in their homes, and children ridiculed and denounced their own fathers and mothers. Loyalty to the Party (and Mao) became more important than loyalty to one’s family. Entire neighborhoods and workplaces were forced to participate in struggle sessions, where victims were publicly hounded and abused by former friends and neighbors. Professors, doctors, and authors were marched through town, signs detailing their crimes posted. Many were beaten to death; others killed themselves. Millions were sent to prison or labor camps or exiled to rural China.

Chinese leaders were purged from the government and the military. Even officials who had once been Mao’s supporters became targets. Millions were thrown in prison or sent away to be “reeducated” through hard labor in the countryside. The legal system ceased to exist. You were assumed guilty until you could prove yourself innocent.

Even the Red Guards turned on each other until Mao Zedong finally had the army intervene to restore order. The Cultural Revolution slowed down by the early 1970s, but how many people did it kill? Estimates range from several hundred thousand to several million. No one can calculate the cost to China’s culture and heritage.

Human and Social Cost

Social trust disintegrated during Mao’s initiatives. Informants reported people they knew, sometimes friends and family. Students ridiculed and turned on their teachers. Intellectuals were targeted and destroyed. Mao’s campaigns took an enormous psychological toll on the nation.

Schools were closed, exams were suspended, and classrooms were politicized. Educated people were abused for their knowledge and experience. Teachers, professors, doctors, and scientists were dismissed. Having “knowledge” could get someone in trouble. “Education was considered suspect,” one survivor remembered. “To know too much was to invite trouble.” China’s scientific and academic communities were set back by years, if not decades.

Children were encouraged to despise their parents. Brothers and sisters turned on each other in Mao’s China. Numerous family members were tortured and killed in front of their relatives. Loyalty to Mao meant loyalty over your own family.

Millions who lived through Mao’s initiatives are traumatized by what they experienced. They suffered through starvation and were forced to live in poverty. Many saw people they knew murdered. Mental scarring from these events lingers, even if the pain is repressed. Children who grew up during Mao’s reign were affected as well.

Precise numbers will never be known. But most estimates of total deaths range from 40 to 70 million people. The Great Leap Forward was responsible for the most deaths, with famines killing between 15 and 55 million. The Cultural Revolution killed several hundred thousand and possibly over 1 million people.

China will never recover what was lost. Countless lives destroyed, families torn apart, and the country was traumatized. Trust was eliminated. And the social fabric of China was forever altered. Millions of people died due to Mao Zedong’s failed initiatives.

Mao Zedong’s Final Years and Legacy

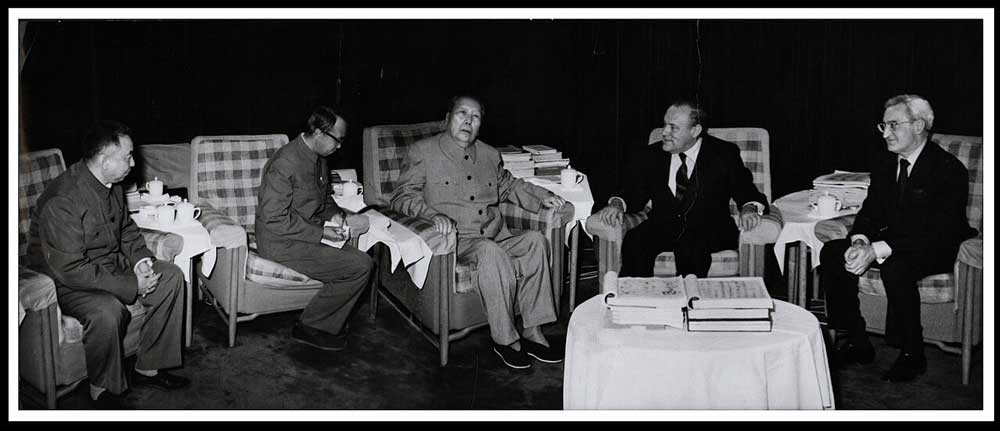

During his later years, effective control of China continued to slip from Mao Zedong’s grip. He became increasingly ill, and true power devolved to competing political factions within the Communist Party. Struggles for dominance among figures such as Zhou Enlai, Lin Biao, and the radical leftist group later known as the Gang of Four became more common. Officials feared making decisions without Mao’s explicit say-so, and the government ground to a halt. China at this time was governed more by politics than policy.

Echoes of the Cultural Revolution persisted through Mao’s declining years. Even as Mao ceded control of day-to-day government, radical upstarts remained active in the political sphere, purge campaigns restarted at random, and paranoia caused officials and party members to hesitate to trust one another. When former defense minister Lin Biao died under mysterious circumstances in 1971 (having allegedly betrayed Mao and begun a coup against him), it exposed just how weakened the system had become. For all that remained of Mao’s power in his later years, it was still enough to keep the country firmly under his control as a figurehead.

When Mao Zedong died in 1976, China was at a relative economic low. Their industries were behind those of most of the world; infrastructure was old and inefficient; agricultural production had yet to return to its previous levels; and years of political isolation had set back development. Reformers after Mao would quietly admit that China had lost 10 years.

The people of China had also suffered greatly. Families were torn apart, education was set back, and professionals were vilified and destroyed. Many who lived through Mao’s reign spoke of having lived in fear. It became common to hear that Chinese people had learned “how to endure, not how to trust” others under Mao. People had become afraid to speak when campaigns were still going on, and that fear did not leave China when they ended.

One thing that never changed was Mao’s status as a quasi-deity in the public sphere. For the Chinese public, Mao Zedong was still celebrated as a hero who had rid China of its imperial past and made it into a world power. His portrait hung over Tiananmen Square, and for years, the party would skirt around judgment of his rule. Mao would be given a sanitized official evaluation years later, labeling his decisions as “70 percent correct, 30 percent mistaken.”

For the millions who suffered under Mao’s regime, there was no such division. To the Chinese farmers who starved, professors who were imprisoned, or citizens who were publicly humiliated by their own country, Mao Zedong was a tyrant personified.

Mao Zedong was a revolutionary who changed China forever. He made China a proud, independent nation, but at what cost? Mao’s reign is a lesson in how power, ideology without regard for truth, and glorification without criticism can destroy humanity.

Reassessment and Historical Debate

The legacy of Mao Zedong has been one of the most heavily debated topics of the 20th century. To many, he is a hero of liberation who unified a country, pushed out foreign powers, and ended a century of humiliation. To others, he is an authoritarian leader responsible for the deaths and suffering of millions of his own citizens. Both sides of this legacy live on today in how Mao is remembered, both in China and abroad.

Proponents of Mao highlight the positive changes he initially brought to China. He pushed Japanese forces out of China and kicked out the Nationalist regime that was riddled with corruption. Land reform and mass mobilization efforts inspired hope in peasants across the countryside. Mao Zedong was seen by many as a symbol of equality and resistance in the late 1940s.

Detractors argue that Mao Zedong’s heavy-handed tactics and disregard for human life became apparent after he solidified his control of China. Policies like the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution were periods when scientific fact was replaced by blind ideology, and incompetence was ignored in the name of loyalty. Historian Frank Dikötter calls Mao’s regime one where “fantasy governed policy.” Policy decisions were dictated to the people from the top down. The truth very rarely reached the leadership.

This proves to be one of the tragedies of Mao Zedong’s reign. Mao established a culture of absolute control, centered on himself. If someone disagreed with him or the party’s policy, they could be written off as counterrevolutionaries or enemies of the people. In such a system, there was no incentive to offer truthful information if it could be used to incriminate oneself. Saber-rattling and exaggeration were incentivized until problems became catastrophes. Ideology was used as a tool to avoid accountability.

Who was to blame for these problems? This question is highly debated. Many believe that Mao’s underlings and provincial officials were to blame for refusing to report accurate projections and quotas when relaying information to the central government. Others argue that you cannot blame individuals when the leader cultivated a culture in which no one dared to tell the truth. Deng Xiaoping himself said of Mao’s regime that “no one dared to tell the truth.”

In China, Mao’s legacy is both remembered and redeemed. The CCP officially calls for reflection on past mistakes while maintaining Mao’s image as the great founder of New China. This stance allows the Chinese government to maintain domestic stability.

Internationally, we can find reassurance in the lessons of history. Absolute power enables absolutist policies that inevitably cause destruction. When ideology is placed over human life, trust within a society is broken. Mao Zedong’s legacy shows us the importance of truth and accountability. More importantly, it shows us the need to limit power.

From Hope to Havoc

The tragedy of Mao Zedong’s China demonstrates what can happen when faith outpaces fact. The rhetoric of hope and liberation became distorted into dogma. Initiatives designed to motivate compliance instead crushed dissent and whitewashed consequences. As one survivor put it years later, “To speak was dangerous. Silence became the only safe language.” Idealism without reality can lead to well-intentioned horror.

Perhaps the most important lesson we can learn from Mao is about the dangers of authoritarianism. Mao had unchecked power and believed he was always right. Totalitarianism became ingrained in the culture of China. Mao Zedong’s reign teaches us one of the darkest lessons of the 20th century: No matter how noble the cause, there must always be checks on power. If there are no systems in place to hold our leaders accountable, hope can become hell on earth.