Queen Boudica’s Last Stand: The Battle for Britannia

The Warrior Queen and the Fate of a Nation

Set in Roman Britain around the mid-1st century CE, this is a story of ancient culture, conquest, and cruelty. Having invaded Britannia in 43 CE under Emperor Claudius, the Roman legions have marched across the southern half of the island, building roads, forts, and colonies, and crushing the resistance of the native tribes. In eastern Britain, the Iceni tribe maintained an uneasy peace, aligning with the Romans and presenting a veneer of loyalty to the Empire. But when the Romans betray them, the Iceni have had enough and are ready to fight.

For, at the heart of the brewing storm is Boudica, the queen of the Iceni tribe and the widow of King Prasutagus. Hoping to protect his kingdom’s legacy, the king had named Rome and his two daughters as his heirs to the throne and to his people. But Rome had other plans, and their response to his death was to plunder the Iceni lands and flog and rape Boudica. She now has no choice but to avenge herself and her people, and she unites multiple tribes against the Romans.

Thus begins one of the most spectacular rebellions in the history of the Roman Empire – a campaign of bloody vengeance that would destroy Roman settlements, cities, and trade and appall the empire – and lead, finally, to a climactic and brutal battle that would shape the destiny of Britannia and Boudica forever.

Background: Rome and the Iceni

When Roman legions landed on Britain’s shores in 43 CE under Emperor Claudius, the conquest marked the beginning of profound upheaval for the island’s tribal societies. While some tribes resisted, others, such as the Iceni of eastern Britain, sought peace through alliance. Led by King Prasutagus, the Iceni became a client kingdom, nominally independent but effectively under Roman influence. The arrangement brought brief stability, but Rome’s appetite for expansion and wealth soon overshadowed its promises.

Upon Prasutagus’s death, he attempted to secure his kingdom by naming both his daughters and the Roman emperor as co-heirs. Roman officials, however, rejected this compromise. Instead, they annexed Iceni lands outright, seized property from the nobility, and treated tribal leaders as enemies. According to Tacitus, the Roman historian, Boudica—Prasutagus’s widow—was publicly flogged, and her daughters were brutally sexually assaulted, a personal humiliation that ignited public outrage.

Historian Dio does not mention these specific abuses in his version of events. Instead, he attributes the uprising to three main factors: the sudden demand for repayment of loans previously extended to the Britons by Seneca; the seizure of funds by Decianus Catus that Emperor Claudius had once lent; and appeals made by Boudica herself. The Iceni believed these debts had already been settled through traditional gift-giving practices.

This betrayal sparked a political and cultural crisis. The Romans had underestimated the depth of tribal pride and unity. The punishment of Boudica was not just an insult to her family but to all Britons under Rome’s heel. What followed was a stunning transformation: Boudica, once queen of a subdued client state, rose as a war leader, galvanizing the Iceni and rallying other oppressed tribes to her cause.

The Trinovantes, bitter from the Roman destruction of their capital at Camulodunum (Colchester), quickly joined Boudica’s revolt. Other groups followed, forming one of the largest tribal coalitions ever assembled in Britain. Boudica became more than a queen—she was a symbol of defiance and a rallying figure for a fractured population seeking revenge and liberation from foreign rule.

The Rebellion Begins

Claudius sent an invasion force to Britain in 43 CE, and Roman legions established a beachhead. Many of the tribes on the island fought against the Roman invaders. However, the Iceni tribe of eastern Britain decided to maintain peace by striking a deal. Led by their king, Prasutagus, the Iceni became a client kingdom of Rome. Although the Iceni were nominally independent, in reality they were not, and Rome considered them a vassal. At first, the Romans kept their word, and the kingdom was left alone. However, the Romans always wanted more; they had an insatiable hunger for expansion and glory, and the Iceni land was rich in natural resources.

When King Prasutagus died, he left the kingdom to both his daughters and the Roman emperor. The Romans, however, rejected this compromise. The Roman governor annexed Iceni lands and looted property belonging to the Iceni nobility. Roman officials rounded up tribal leaders to be dealt with as enemies. Tacitus, a Roman historian, writes that Boudica, the widow of Prasutagus, was flogged and Roman officials raped her daughters. The Romans had defied their agreement, and Boudica sought vengeance not only for her family but for her people.

The Roman historian Dio does not include this information in his historical account. In his version of events, three primary causes of the rebellion are cited. These include Seneca demanding the Britons repay loans they had previously received from him, Decianus Catus taking away a large sum of money Claudius had earlier loaned to Boudica, and speeches made by Boudica herself. The Iceni believed these loans were gifts.

The Iceni were surprised and humiliated by Rome’s action. A political and cultural crisis had begun. The Iceni and other British tribes took great pride, and the Romans had forgotten this. Boudica had not only been flogged in front of her household, but in front of Roman occupiers. All Britons were insulted by Rome’s actions, and retribution was needed. The Romans had created a war leader in Boudica, a former queen of a Roman client state.

The Iceni took up arms, and the Trinovantes quickly followed. The Trinovantes had been especially humiliated by the Romans; the Romans had built a new city on top of their old capital, Camulodunum (Colchester). Many other tribes joined, forming one of the largest tribal alliances in British history. Boudica was no longer just a queen, but the figurehead for a fractured population seeking revenge.

Queen Boudica’s Rising Fury: From Revolt to the Edge of the Final Battle

As the rebellion sparked by Boudica’s personal injustices grew into one of the most formidable of all anti-Roman uprisings in Britannia, Boudica’s was the face that defined it for many. Tacitus records her words to be imbued with a “fierce and commanding presence” and claims she incited Britons to “avenge with fire and steel their common freedom and the sanctity of groves and altars.” No historical source can accurately estimate how many Britons were enraged enough to join the revolt, but what is known is that tribes of the Iceni, Trinovantes, and others who may have had their own historical grievances against the Romans coalesced into a tide of revolt behind her.

The first objective of Boudica’s newly united Britons was Camulodunum, Trinovantian capital and recent home of a Roman colony. The town, which housed Roman veterans who had mistreated the local Britons, was notably reliant on a walled temple to Claudius, built around the time of the conquest, as a defensive stronghold for its inhabitants. These buildings fared little when Boudica’s forces arrived. Tacitus writes that the townsfolk took refuge in the temple and held out for two days, before the temple itself was stormed by Boudica’s forces.

Archaeological excavations have confirmed a similar scale of destruction to that described by Tacitus, and at least one ancient source alludes to the burning of the town. The message of these events reached Rome, where previously secure Britannia had rapidly become a very different place.

It took little time for the revolt to spread, and with remarkable speed, Boudica’s Britons advanced on Londinium, a large, wealthy, and thoroughly Romanised city, yet it was also a place with little in the way of protective walls. Suetonius Paulinus, the current Roman governor of Britannia, having been delayed in his return from campaigning on Anglesey, quickly estimated Londinium to be indefensible and ordered it to be evacuated. There was no Roman military presence in the city when Boudica’s Britons arrived, and accordingly, the town was burned.

The behaviour of Boudica’s Britons has been reported to have left the townsfolk of Londinium with little time to put up resistance. Ancient authors such as Tacitus and Dio Cassius have reported that buildings collapsed as people rushed through narrow alleyways, attempting to reach the Thames riverbank. Londinium lay waste, and the Britons moved north to their third target: Verulamium, a Romanised town of seemingly major economic importance to Roman interests, and home to a reported 15,000 inhabitants at the time.

There is strong evidence that Britons came into the settlement by one route and fanned out to strike with great numbers when in a position to do so, a scene of chaos recorded by Dio Cassius, who described Verulamium as burning from “three distinct fires.” The scale of the Roman Britons’ defeat is clear by the occupation layer of burnt debris, which at the time would have reached up to two metres in height.

Britons had torched three major Roman settlements, and thousands of Roman Britons and veterans had been killed, and with them, the revolt reached its most powerful momentum. The Romans were on the back foot, with dispersed legions and a route north that was swarming with refugees and occupied outposts. The momentum of Boudica’s Britons was as formidable as it would ever be; however, without a doubt, there were major issues that such an army faced, and Boudica herself led some of the biggest of these issues.

No Roman source can reliably state how large Boudica’s army was. Still, Dio Cassius estimates the number of Britons at around 230,000, with every family possessing a stake in Boudica’s revolt in one way or another. Boudica’s Britons were massive in number, but the logistics of such a feat were becoming harder to overlook. Vast swathes of southeast Britannia faced severe risk of supply shortages. The behaviour of her Britons had corrupted the initial spirit of the revolt and, in many cases, led to anarchy, as looting occurred when Boudica and her Britons set about attacking Roman outposts on the march to Londinium.

Suetonius, in the meantime, had been taking stock of the situation and, after a long march to consolidate his position, had set about the task of engaging Boudica’s Britons in a last-ditch attempt to stop the revolt. The Roman forces’ position was strategically located in a narrow defile, with a large forest behind them to prevent the Britons from outflanking them. Boudica marched up the battlefield to engage the Romans; at the time, her forces were at their most numerous, but they had reached the end of the line. Britons were charged by emotion, by what they had suffered and what they had gained. They were prepared for battle; Rome was too.

The Battle for Britannia: Boudica’s Last Stand

The climax of Boudica’s revolt was a battle fought on Watling Street, an ancient Roman road running across southern Britain. Roman governor Suetonius Paulinus selected the battleground carefully. He drew up his much smaller but disciplined force in a tight space between the woods, so that he prevented the larger British army from surrounding his troops. The geographer Tacitus estimates the British forces at 230,000, although modern scholars consider this number an exaggeration. With this tactic, the Britons could not use their numerical superiority.

Boudica’s large army mainly consisted of British tribal warriors and, bringing up the rear, her wagon train, in which many women and children rode. The Roman forces comprised about 10,000 legionaries, mainly veterans of the XIV and XX Legions, along with some auxiliary forces. They closed their ranks and, armed with pila (spears) and gladii (short swords), they waited for the enemy charge.

Tacitus writes that the Britons advanced in a massive, roaring crowd. They screamed and waved their primitive weapons, while the Romans “received their first attack with a flight of javelins”. As they reached the Roman lines, the Roman soldiers thrust their shields forward and in wedge formations, they “pressed into the enemy”. Boudica’s warriors were massacred. Unable to escape, the Britons and their wagons formed a blockade behind them, and their bodies formed a barricade on which the Romans trod.

Tacitus and Dio claimed 80,000 Britons killed, and Boudica’s army wiped out, although it is uncertain whether this number refers to the soldiers only or the total number of Britons in the routed army and wagon train. The revolt was now over. Boudica’s head was a prize to the Romans, and a free Britannia died on the battlefield of Watling Street. The Romans had triumphed. As proof, Boudica’s skull was paraded through the streets of Rome on the chariot of a victorious general.

Boudica’s end is shrouded in mystery. According to Tacitus, Boudica poisoned herself so as not to be taken captive by the Romans. Cassius Dio claimed she fell ill and died, and was given a lavish funeral pyre. Boudica’s revolt may have been Rome’s greatest disaster in Britain since AD 43, but her legend would outlast the empire itself. To the Romans, she was a mere rebel. To the British, and to generations to come, she would be an iron queen who fought back against the empire.

The Aftermath and Roman Reassertion

In the aftermath of Boudica’s defeat, Rome took decisive action to quell any remaining resistance in Britain. The governor, Suetonius Paulinus, exacted harsh reprisals on the tribes suspected of supporting the rebellion. Whole settlements were razed to the ground, and those captured were executed en masse. Tacitus writes that the ferocity of the Roman reprisals was not well-received even in Rome, where some criticized the excessive measures taken against the Britons. The intention was to set an example and discourage any future dissent.

Politically, the heavy-handed Roman response to the rebellion was not without cost. The more conciliatory Publius Petronius Turpilianus soon replaced Suetonius. His rule marked a shift in policy, away from antagonizing the native population and towards more subtle methods of control. Rome focused on infrastructure development, trade, and cultural assimilation to solidify its hold on Britain. The process of Romanization accelerated, but the memory of the Iceni queen’s rebellion lingered in the collective consciousness of the island’s inhabitants.

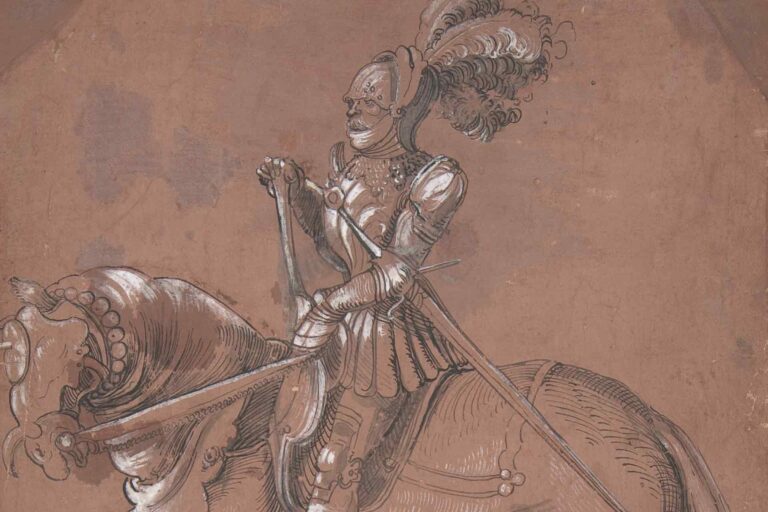

In the centuries that followed, Boudica’s image gradually shifted from that of a ruthless upstart to a heroic figure resisting a foreign power. Medieval and modern British writers resurrected her story as a national symbol of resistance. During the 19th century, the reign of Queen Victoria saw Boudica elevated to a romantic, imperial icon of anti-Roman defiance. Her bronze statue near Westminster Bridge, hoisted on a rearing horse, is a monument to that mythologization. The real Boudica, however, remains difficult to know, her motives and voice obscured by the Roman sources.

The ancient historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio provide vivid portraits of Boudica and her uprising, but they reveal little of the queen’s interiority or that of her people. A native British account of the rebellion, if it existed, has not survived. Modern historians are left to interpret the Roman sources, often skewed to aggrandize the empire and its eventual triumph. The silence of the Britons on this matter leaves many questions unanswered, especially regarding Boudica’s daughters.

The two daughters of Boudica, whom Tacitus says were raped by Roman soldiers, are mentioned no further after the battle. What became of them, or even if they survived, is unknown. In the wake of the fight and Boudica’s death, they too fall silent, and little more is heard of them. The erasure of their voices is a small but potent reminder of the costs of empire.

Legacy of Boudica and the Battle

Boudica’s uprising, while not ultimately successful, remains a testament to the power of rebellion against imperial rule. The warrior queen’s defiance against Rome sent shockwaves through the annals of British history, symbolizing the unquenchable thirst for freedom that is ingrained in the human spirit. As the Roman historian Tacitus once wrote, the Iceni revolt “arose out of grievances deeper than pride.” In this way, Boudica’s name will be remembered as the voice of a people who refused to be silenced.

In the centuries that followed, Boudica would rise to prominence once again as Victorian nationalists and poets retold her tale in the 19th and 20th centuries. In this way, Boudica became reimagined as a national symbol for a new imperialist Britain at the height of nationalism. A fusion of legend and myth, many Victorian writers and historians romanticized the story of Boudica as a narrative of resistance and national pride. As a result, Queen Boudica became the figurehead of British cultural memory.

Today, a large bronze statue of the fierce queen stands outside near Westminster Bridge, built in the early 1900s. Perched on her war chariot, with her long, flowing hair and her two daughters beside her, the sculpture has become a reminder of Boudica’s enduring legacy. Yet this statue is both a romantic and a political image—a symbol of anti-imperial defiance at the heart of the British government. In her rise to notoriety in the 20th century, Boudica would become both legend and martyr.

Yet we are still left with the question of how to best remember Queen Boudica. Was she a tragic and heroic figure, doomed to fail against the power of Rome? Or was she a timeless symbol of national pride, an early embodiment of anti-imperial resistance and defiance? These are questions that historians and Britons have yet to fully answer. It is undeniable that Boudica’s rebellion was at its heart a violent and desperate act, but so too was the Roman response.

The Battle for Britannia was both more than a war and less than a war. It was a clash of empires, a fight between two different cultures and value systems. The conflict laid bare the courage of the oppressed and the callousness of the conquering nation. In the final battle, both the heroism and the tragedy of the struggle were illuminated, for it is only in reflecting on the past that we can come to understand freedom and its price.

It is for this reason that we must reject the Roman accounts and the lens through which they saw Boudica. In a reimagining of her legacy, we must recognize Queen Boudica as a symbol of the voiceless, as a champion of a people who would rather burn their world to the ground than kneel before a tyrant. Her final battle was not a tragedy, but a battle cry that still echoes through the ages.