Rome in Ruins: The Sack of Rome in 1527

The Sack of Rome in 1527, marks the tragic descent from a peak of Renaissance splendor to the chaos of imperial armies overwhelming the Eternal City. Artists, clerics, and scholars, once celebrated in palaces and basilicas, now found themselves the targets of looting, violence, and terror on a scale previously unimaginable. Contemporary accounts speak of “a darkness over Rome,” echoing the incredulity of a society watching its cultural and spiritual epicenter unravel in mere hours.

The events leading to this calamity stemmed from escalating tensions between Pope Clement VII and Emperor Charles V. Their power struggle fractured the fragile balance of Italian politics. As the emperor’s unpaid and mutinous troops grew restless, the situation spiraled beyond anyone’s control. The sack of Rome in 1527 was not merely a military catastrophe; it was a cataclysm that redefined the cultural, political, and spiritual trajectory of Europe.

Europe on the Brink: The Road to 1527

Europe was a continent deeply fractured along political lines. In the Italian Peninsula, the established equilibrium of power had given way to a more contested scenario by the time of Clement VII. The pontiff and Charles V found themselves at odds over the extent of Habsburg influence in Italy. Clement’s apprehension of Habsburg encroachment and Charles’s perception of papal duplicity fanned the flames of mutual distrust. The political landscape was thus set for small provocations to metastasize into significant crises, with both sides interpreting actions as veiled hostility, setting the stage for a Rome that would soon find itself on the brink of disaster.

The coalition of 1526, known as the League of Cognac, marked a significant shift in the balance of power. France, Venice, Florence, and Milan sought to curtail Charles V’s influence in Italy, and Clement VII ultimately aligned with this league in 1526, lured by the prospect of a more balanced power dynamic. However, the League of Cognac was hamstrung by a lack of cohesion and coordination, leaving Rome increasingly vulnerable. The Eternal City, as both a symbolic and tangible prize, was eyed by those looking to weaken the pope’s standing. A strike against Rome would serve not only as a blow to the pope himself but also as a destabilizing act against the alliance arrayed in his defense.

Economic distress further exacerbated the situation. The demands of war were beginning to take their toll on all the powers involved. Shortages of supplies, food, and wages were starting to create discontent and difficulties within armies.

In an era where the logistics of campaigning were often unreliable, the ability to make promises without the means to fulfill them was being tested. The precarious financial situation led to frayed nerves and the potential for insubordination, with soldiers conditioned to expect regular pay finding themselves in a state of growing desperation.

Religious division also played a crucial role. By the 1520s, Lutheran ideas had begun to gain a foothold across the German states, fostering a climate of religious dissent with direct implications for Rome’s standing. The spread of Reformation thought contributed to an atmosphere of anti-papal sentiment that reached new heights during Clement VII’s pontificate. Political and religious fractures were increasingly visible, with the papacy’s spiritual authority more directly challenged than at any point in the previous century.

The cumulative effect of these elements by early 1527 was to create a volatile situation on the precipice of disaster. The political machinations had left Rome in a state of strategic exposure, the League’s defense was showing signs of weakness, and the forces of reform and insurrection were on the move. It was into this powder keg that the events leading to the Sack of Rome would soon erupt, setting in motion a sequence of events that would dramatically alter the course of the Renaissance.

The Imperial Army: A Powder Keg Ready to Explode

The army that advanced on Rome in early 1527 was a temporary alliance of European soldiers. Its backbone consisted of thousands of German Landsknechts, professional mercenary infantrymen known for their ferocity in the field and unpredictability when unpaid. They were accompanied by experienced Spanish veterans of the Italian Wars and a smaller number of Italian forces in the service of the Holy Roman Empire.

This diverse army was effective but not cohesive; these troops spoke different languages, followed different tactics, and were paid with the expectation of sharing plunder and little else. The Landsknechts in particular were hostile to the papacy. Protestant ideas had spread among them during the war in Germany, and many had been exposed to teachings that challenged Rome’s power.

The force was led by Charles de Bourbon, a Frenchman who had risen to the rank of general in the imperial army after falling out of favor with Francis I. Bourbon was a competent commander, but he was not popular with his troops and was in no position to order them around. In part, his power rested on the respect he commanded and his soldiers’ anticipation of dividing the spoils.

A chronicler of the campaign would later write that Bourbon “advanced with an army which he did not command, but only accompanied.” As the force moved south, its condition declined. Wages were not paid, and the troops were often hungry and sick. They subsisted on foraging and looting as they marched, and their spirits changed as Rome loomed closer. The city became, for the men, “the city that would pay the emperor’s debts.”

Mercenaries who were not paid were known for being dangerous, but these soldiers were particularly so. The Landsknechts’ religious beliefs gave them additional motivation for marching on Rome; some saw the prospect of sacking the city as a chance to target the Catholic Church. The Spanish and Italian soldiers also had their reasons for embracing violence. The veterans of the Spanish units had no strong loyalty to the emperor and wanted to take their chance at getting their wages and a share of any loot. The Italian recruits had joined the army because it was the only option left to them. These reasons were different, but they all led to the same place.

As Bourbon’s power over the army waned, he attempted to slow his forces in the hope of receiving more supplies and wages. The troops threatened to mutiny, and according to some contemporary accounts, some soldiers shouted that if Bourbon would not take them to Rome, they would march without him. Bourbon could not risk losing the army; as far as he was concerned, he had no choice but to continue the march.

By the time the army arrived in front of Rome, it was a mob of starving and exhausted men, driven by the thought of what lay beyond the city walls. Add to this the fact that Bourbon was killed at the start of the siege, and it was an army of men with nothing to lose and little to direct them. It is little wonder that the Sack of Rome was one of the bloodiest events of the Renaissance.

The March Toward Rome

The imperial army marched slowly through central Italy throughout the spring of 1527, its composition and pace increasingly ragged and desperate. Soldiers in the German, Spanish, and Italian units were tired, hungry, and fed up with a months-long dry spell in pay. According to contemporary chroniclers, men moved through mud and rain with scant food and growing certainty that only in Rome would they at last be given the wages that had been long promised to them.

Motivated by this growing sense of urgency, the army pushed its march through central Italy at an accelerating pace, as the towns through which it passed could do little to resist or impede the combined force’s advance. As the army neared Rome, it became clear that the soldiers were about to take part in a desperate gamble: one that the newly-constituted city was unprepared to resist.

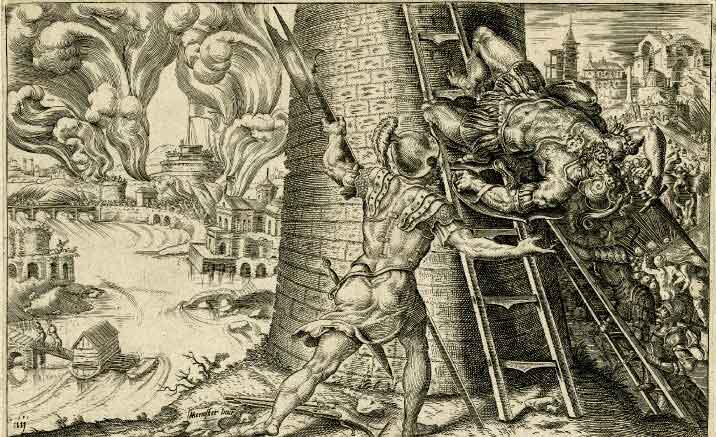

Upon the imperial army’s approach, Charles de Bourbon took a decisive step to enforce discipline upon its ranks. When the assault began on the morning of May 6, Bourbon rode at the head of the initial wave of attackers. Covering his armor with a white cloak to make himself recognizable to his men, the constable moved closer to the walls under the cover of his men’s fire. But Bourbon was struck down almost immediately upon the start of the assault.

The death of the army’s leader at such an early stage in the attack would have a decisive impact. According to eyewitness testimony, at the very moment when leadership was most urgently needed, the army “lost its guiding hand,” leading to confusion and disarray among the ranks.

Without an obvious authority to direct their operations, the imperial soldiers who took part in the attack fought in disorganized, desperate groups. Units that had marched side by side for months were now acting entirely on their own, motivated more by desperation and a sense of urgency than by organized command. The Roman defenders were not ready for the unstructured advance. While they had been expecting a siege of some sort, the extent and disorganization of the pressure on various points along the walls was a shock to the defenders. The rapid loss of leadership among the attackers created a new, dynamic pattern of combat that Rome was ill-prepared to respond to.

The force that had been mustered to defend Rome was a local militia, hurriedly gathered and untested. Most of its members had little or no military experience, and now found themselves pitted against the hardened, veteran soldiers of the imperial army. After breaches were made in the walls at several points along the walls, the defenders were unable to form or maintain a coherent line.

Panic and disorder set in quickly, debilitating the city even further. As the attackers pressed in, Rome’s strategic vulnerabilities became clear. The city was not prepared for a lengthy attack, and the quality of its walls and fortifications was varied and often poor. The imperial army had made the great Italian capitals of the day its target, and their fortifications were not ready for a test of this sort.

Communication between the defenders’ units was hampered under the pressure of the assault, and many of Rome’s commanders were unable to coordinate their response adequately. By the time meaningful resistance began to be organized, the attackers had already taken footholds in multiple districts. In the middle of the day, the imperial army had forced its way into Rome with little more than momentum and disarray to guide it.

The fall of Charles de Bourbon in the opening stage of the assault, intended to inspire heroism among the attackers, had in fact created a void that hastened the disintegration of Roman defenses. Marching with an increasing desperation brought on by economic hardship and a general loss of discipline in the ranks, the assault was equally disorganized: urgent, and once started, unstoppable.

The Sack Unleashed

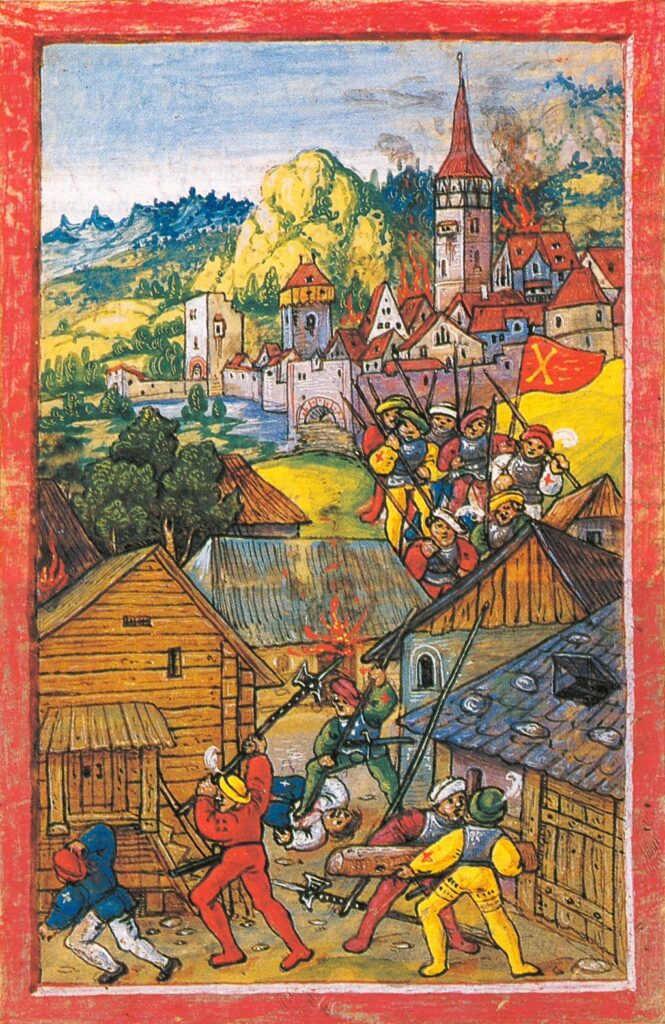

Under heavy rain and gunfire, soldiers scaled ladders, smashed weakened gates, and poured through gaps in the walls near the Janiculum. Soldiers exploited the initial breaches of Rome’s walls, and within minutes, order and discipline were lost. The city was immediately consumed by violence. The initial hours of the sack have been described in later historical and literary works as a “whirlwind of iron and fire”.

A day of indiscriminate mass killing followed, as troops rampaged across the city with little or no restraint. Churches and other places of worship, previously considered to be out of bounds, were looted and defiled in the city centre, and by troops venting the frustration of months of near-starvation and ideological enmity against the papacy.

Following the initial phase of unchecked violence, the sack took on a more “organised” nature. The troops forcibly entered many palaces, monasteries, and libraries and looted them of their wealth, often accumulated over centuries. Priceless manuscripts were burned or sold for a fraction of their value, while artworks were carted away as trophies or to extort higher ransoms.

Houses were also ransacked systematically and comprehensively, and treasures accumulated and passed down over the centuries were looted and sold within days. For a large part of the city’s population, it was no longer possible to hide or protect their accumulated wealth: imperial soldiers poured through every cellar, well, and even grave in the city looking for valuables.

A structured ransom market emerged in the following days, as a second phase of the sack. Nobles, clergy, merchants, shopkeepers, courtesans, and even artists were rounded up, kept captive, and released upon payment of an exorbitant sum of money. Entire families sometimes surrendered their life savings in exchange for a relative’s freedom. In many cases, however, victims could not afford the ransoms and were routinely humiliated, abused, and stripped naked. Many of the captives were traded between soldiers who had them at their disposal: imprisonment was, in effect, transformed into a profitable business. Even after the captives had gathered the requested sum, troops often returned to extort more money from them.

Against this backdrop of “organised” plunder, murder, rape, and torture were rampant, as reports of atrocities committed throughout the city circulated. There were few apparent distinctions made between social class, nationality, or religion. Accounts of forced baptisms abounded: members of the clergy, in particular, were said to have been forcibly baptised after being held for ransom or at the point of a sword. The violence was indiscriminate and widespread. In all quarters of the city, formerly peaceful streets were turned into killing fields. The psychological damage to the city’s residents was significant: its effects would linger for years after the sack.

The violence perpetrated upon Rome, the very heart of Renaissance culture and faith, was described by those who lived through it as an apocalyptic rupture: the sack was experienced by many as the shattering of a myth, the city’s long-held belief in its own invincibility, when faced with the realization of its own vulnerability. The sack had not only physically decimated the city. The psychological, spiritual, and cultural losses it caused were described as nearly incomprehensible: years of artistic and scholarly progress came to an end overnight. Religious institutions, symbols of stability, were defiled in ways that would remain deeply ingrained in the city’s collective memory.

Inside the Sack of Rome: Voices from the Besieged City

Accounts of the sack’s experience from within Rome are some of the most important primary sources from the siege. Letters written by priests, merchants, and diplomats offered vivid, often harrowing descriptions of a city on the edge. “The streets are full of cries, for, it seems, every hour there are cries of battle,” one Florentine messenger reported as panic set in early in the sack. “The whole city was changed to tears,” echoed a Roman priest whose family huddled in a cellar during the battle.

On the one hand, these messages emphasize the sense of hopelessness that seized Rome’s inhabitants once the breaches were made and war came to the streets. So swift and violent was the advance of the invaders that the population, conditioned by months of siege to expect a peaceful resolution, found itself wholly unprepared for a rout.

On the other hand, the approaching famine and disease quickly spread through the trapped city. Food supplies were looted, markets closed, and deprivation spread. Many of the prisoners sent home with stories wrote of filthy, cramped conditions in which hunger and disease killed at alarming rates. “Plague walked the streets as freely as the soldiers,” one captive from the Condottiere’s regiment told his family on a return trip north. A lack of order and supplies thus compounded the misery inside the walls.

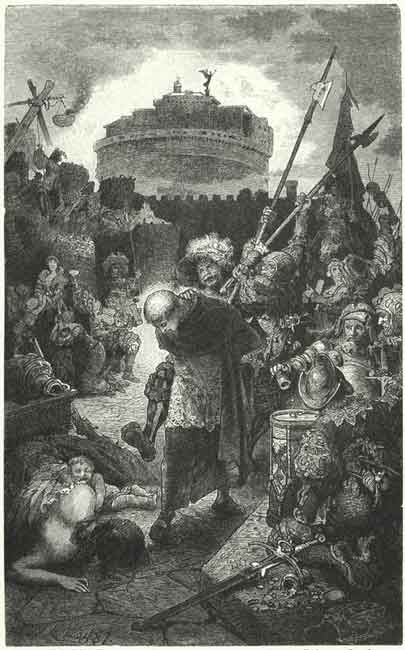

The story of the Swiss Guard remains one of the most famous events to occur in the sack of Rome. The heavily armed troops had been assigned the task of defending the pope and chose the steps of St. Peter’s Basilica as their position. Faced with a flood of armed attackers, the Swiss nevertheless held their ground.

They held off the attackers as long as was humanly possible, outmanned and outgunned: less than 200 Swiss Guards defending the Vatican against thousands of imperial troops. Historical records show how the Guards formed ranks at the bottom of the steps to St. Peter’s and held their position as a storm of attackers surged over them. Accounts of the day tell of how they “stood in array like a wall in defense of the holy seat,” as their number was gradually reduced.

“They were the final shield of the Church,” and took wave after wave until almost all were dead: 147 out of approximately 189 Guards killed in what has become one of the most famous last stands of all time. Their sacrifice gained Pope Clement VII just enough time to escape via the Passetto di Borgo, and ensured the papacy survived even as the city fell.

It was this sacrifice that made possible one of the sack’s most cinematic moments. Clement VII and a small entourage escaped through the Passetto di Borgo and into Castel Sant’Angelo. The elevated and fortified passage connected the Vatican directly to the castle and ran over and through buildings on the city side. Witnesses later described the pope racing across the corridor while the battle raged just behind him, having “crossed the threshold of the palace with the weight of Rome on his shoulders.” The pope’s flight was thus successful, and the papacy was able to outlast the siege. However, Rome itself was mainly left to its own devices.

Survivors of the sack later described the city as unrecognizable. Citizens often reported aimlessly wandering their own neighborhoods, lost in the destruction. Churches were desecrated, houses destroyed, and the city’s cultural life was, to all intents and purposes, over. From within Rome, the sack felt very much like an apocalyptic event. The firsthand accounts from the time are raw, frightened, and eminently human, as much a record of the emotional and spiritual shock of the sack as of the violence itself.

Taken together, the first-person accounts of the Sack of Rome from both the attacking and besieged camps offer one of the best primary source windows into the event. Letters, diaries, chronicles, and eyewitness accounts from the period capture the lived experiences of those in Rome during the sack. They preserve a history of famine, imprisonment, bravery, and despair, allowing future generations to witness how a capital of Renaissance culture and power was turned into a landscape of devastation.

The Human and Cultural Cost

The 1527 sack of Rome resulted in the deaths of thousands of civilians and soldiers. Many perished in the initial fighting and the chaotic, brutal days that followed. Exact figures are hard to determine, but numerous sources give estimates of 6,000 to 12,000 victims in the first phase of the disaster. Disease and starvation further decimated the city. “Death walked the streets as freely as the conquerors,” wrote one eyewitness.

The sack also had a profound impact on Rome’s cultural life. Before 1527, the city had been a vibrant center of Renaissance art and culture, a magnet for painters, architects, humanists, and scholars. The sack scattered many of these, weakening Rome’s cultural hegemony. Artistic luminaries such as Parmigianino and Benvenuto Cellini, as well as countless minor figures, left Rome and took their talents to other courts and cities, such as Florence, Bologna, and beyond.

The sack also quickened the shift from the harmonious balance of High Renaissance art to the more mannered, distorted style of Mannerism. Artists who remained or returned to Rome were influenced by the trauma, producing work that was more restless, more skewed in its proportions, and more emotionally charged. The stability and optimism that had marked the early Renaissance in Rome gave way to a darker, more anxious aesthetic. Historians have remarked that “the world had changed, and art changed with it.”

Rome lost not only its artists but also many of its cultural treasures. The sack saw palaces, churches, and libraries ransacked or destroyed; many of the manuscripts that had survived the fall of the ancient world were lost in a matter of days. Works of art were melted down or broken up, while others were carted off to foreign lands to be sold or used as diplomatic gifts. Chroniclers spoke of the sack as “a wound upon learning itself,” as entire collections of ancient and Renaissance texts were lost.

The impact on knowledge and scholarship was immeasurable. Libraries and archives that had been the repositories of humanist study were gutted. Political, religious, and civic records that spanned centuries were scattered, lost, or destroyed. The disruption to Rome’s scholarly community was severe, with much knowledge lost that future generations would need to recover or rediscover. For contemporaries, the cultural damage was as harrowing as the physical destruction.

In the sack’s wake, Rome lay not only empty and poor but also, in many ways, artistically and spiritually depleted. The human and cultural costs of the 1527 sack were a turning point, marking the end of the Renaissance city’s golden age and the beginning of a new and uncertain chapter.

Deutsch: Sacco di Roma (1527)

Political Consequences

The political effects of the Sack of Rome were almost immediate, starting with a massive humiliation for the papacy. Pope Clement VII, who had tried to act as a mediator between France and the Holy Roman Empire, was himself taken prisoner by imperial troops. Imprisoned in the Castel Sant’Angelo, the pope spent several months negotiating his release with imperial commanders and eventually agreed to pay a huge ransom, emptying out the depleted treasury of Rome in the process.

He remained a virtual prisoner until he paid the ransom in full, with the combined effect of the events leading to diminished prestige for the papal office and a newly undermined perception of the strength of the Papal States, whose defenses against an imperial invasion had proven woefully inadequate.

The effects on the papacy were demoralizing, with Clement VII’s prestige damaged and papal authority in the Italian peninsula crippled for the following decades. The Papal States, already a major power in Italy before the Sack of Rome, was further divided and economically ruined in its aftermath. Many cities which had previously been in good standing with the papacy reevaluated their positions and allegiances, while many local Italian nobles used the opportunity to assert their independence from the papal authority.

The pope’s failure to prevent the sack or to protect the citizens of Rome from its effects tarnished the Church’s image as a moral and political leader at a time when that position was increasingly challenged by reformers from both within and outside the Church. The political situation in central Italy quickly changed as the papacy entered a period of relative rebuilding and retrenchment.

The Sack of Rome, on the other hand, considerably strengthened Charles V’s position. Although the emperor did not specifically order the sack, it worked to his benefit in several ways. It effectively ended the League of Cognac and, by extension, any organized opposition to imperial authority in Italy, as the secular and religious leaders of Europe quickly recognized that the Habsburgs had clearly emerged as the dominant power on the continent. Charles now had the upper hand in negotiations with Clement VII and was able to bring the pope to reconciliation with him on imperial terms.

The political situation in Italy was now reordered with Habsburg dominance, as Charles secured his hold on Naples and Milan, which, when combined with the existing Habsburg territories in northern Italy and the recent capture of Tuscany from Florence, created a near-continuous string of imperial lands from the south of Italy up into the Alpine region. France, previously one of Charles’s major Italian rivals, was forced to give up many of its competing claims south of the Alps. Many Italian city-states, which had previously relied on playing the larger powers off of each other, or taking refuge under papal protection, now changed their calculations, opting to court Habsburg favor rather than that of the papacy.

The effects were also felt throughout the rest of Europe, with many rulers now having seen how quickly the balance of power could change and how easily the papacy could be humbled. Charles V’s consolidation of authority in Italy helped solidify the position of the Holy Roman Empire at a critical moment during the early Reformation and gave him greater sway over both Catholic and Protestant states on the continent. In short, the Sack of Rome was not just a disaster for the city but was also a geopolitical event that changed the basis of European authority.

Aftermath: Rebuilding a Broken Rome

In the immediate aftermath of the Sack of 1527, the city of Rome had an empty quality, with large parts of it seeming to have been hollowed out. This was the result of the wholesale abandonment of whole districts by large sections of the population, many of whom were killed, fled, or forcibly displaced. Before the Sack of Rome, the population of Rome, then believed to be more than 55,000 people, had been halved by the combined effects of death, emigration, and flight.

Once all the dead had been buried, those who were able returned to aid a city with a fraction of its former population. Houses needed to be repaired, churches restored, and even rudimentary order reestablished. Trade was at a standstill, famine still lingered on, and food supplies would take time to recover. Rebuilding the city’s fabric would be slow due to a combination of financial insolvency and political uncertainty. With no work to do, artisans and laborers tried to find something to do; families returned; and everyday life was, to some extent, restarted in the months after June 1527.

Economic recovery from the sack was slow and often painful. Nobles who had been robbed of their wealth had to sell their lands or artworks to get by. Merchants needed to restart trade in a city whose very infrastructure had been shattered. Slowly and against the odds, the city began to recover in the years after the Sack. Small numbers of foreign merchants, bankers, and new artisans started to trickle back to the city, enticed by its long-term historical importance.

Important civic buildings and churches were repaired and improved. Roads and bridges were restored. Markets reopened, and the civic administration of Rome began to function once more. There was a long-term demand for housing, so rebuilding for those displaced by the Sack was necessary. The recovery of the city was a long, drawn-out process that would take many decades to show visible signs of success.

The shock waves of the sack of Rome were religious as well as physical and political. The sack was a humiliation for Clement VII that, combined with the damage to the city itself, led many in the Church to conclude that the time for reform was long overdue. The event itself did not cause the Counter-Reformation. Still, the aftershocks of 1527 made many inside and outside the Church more receptive to reform and heightened the reform movement’s sense of urgency.

Many church leaders also took the sack as a warning from God to the Church to reform itself, placing greater emphasis on the spiritual formation of priests and clergymen. This included greater attention to clerical morality, the education of churchmen, pastoral work, and the suppression of curial corruption.

In time, the rhetoric became action. Seminaries were established, and the activities of monastic orders began to be governed more by the rules they professed. Greater attention was also paid to corruption within the curia itself. The measures introduced by later popes, particularly Paul III, set the stage for the Council of Trent, which would change the face of Catholicism for centuries to come. The sack of Rome, then, became the starting point for a process of internal Church reform and renewal.

In the longer term, the recovery of Rome involved not only the rebuilding of its physical fabric but also a cultural and spiritual renewal. It was only as churches were rebuilt and artistic commissions resumed that the city regained some of its lost vibrancy. The memory of 1527 was indelibly etched into the city’s history and into the consciousness of the Church itself. It had long-lasting effects on how the papacy presented itself in Rome and to the broader world.

In the process, the city was not just restored to its former self, but it was also transformed, a new city defined by both the trauma it had suffered and by reform and renewal. By the mid-16th century, Rome had begun the process of reasserting itself as a major centre of faith and culture, having broken the Renaissance city and built something different in its place.

Legacy of the Sack

The sack of Rome in 1527 is often seen as a pivotal moment in European history, marking the abrupt end of the city’s Renaissance Golden Age. In the lead-up to the disaster, Rome was a thriving cultural, artistic, and architectural hub, characterized by intellectual vigor, boundless creativity, and grand aspirations. In its aftermath, the Eternal City became a symbol of ruin, with looted palaces, a traumatized population, and a shattering of its previous confidence and self-image. The incident is often referred to in contemporary chronicles as “the day Rome remembered its mortality,” and in many ways, this apocalyptic trauma became embedded in the city’s cultural memory.

The legacy of the sack of Rome extended far beyond the city’s walls and continued to reverberate across Europe for centuries. The shock of the event exposed the vulnerability of even the most culturally and spiritually prestigious cities. It served as a harsh reminder to both rulers and ordinary citizens that political influence did not necessarily equate to protection. Artists and scholars who managed to flee the city took their tales of Rome’s fall to courts all across Europe, spreading anxiety and fueling artistic and literary trends for decades to come. The emotional resonance of the event would also play a role in Europe’s transition from the Renaissance into a more introspective and uncertain age.

The political implications of the sack were not lost on Europe’s leaders either. Pope Clement VII, who had entered the year with the arrogance of a near-absolute ruler, learned the hard way about the disastrous consequences of political missteps and overconfidence. The near-collapse of the papacy demonstrated that spiritual supremacy was no match for military force.

Italian city-states that had long engaged in a precarious balancing act of alliances and rivalries had cause to reflect on the folly of dismissing imperial power or overestimating the guarantees of diplomacy. The sack of Rome was a brutal demonstration that even the greatest cities could be brought to their knees in a matter of days if the political edifice on which they were built was not solid.

The sack of Rome also left a grim lesson about the dangers of mercenary armies. The unpaid and hungry troops of the Holy Roman Empire, who had run amok in the city, demonstrated how easily mercenaries without a real cause or a chain of command could turn a military conflict into a humanitarian disaster. In the years that followed, many European rulers would rethink their approach to mercenary forces. The sack of Rome was, therefore, a complex legacy, serving as an enduring reminder of the price of hubris, the perils of political instability and military imbalance, and the unchecked violence of war.