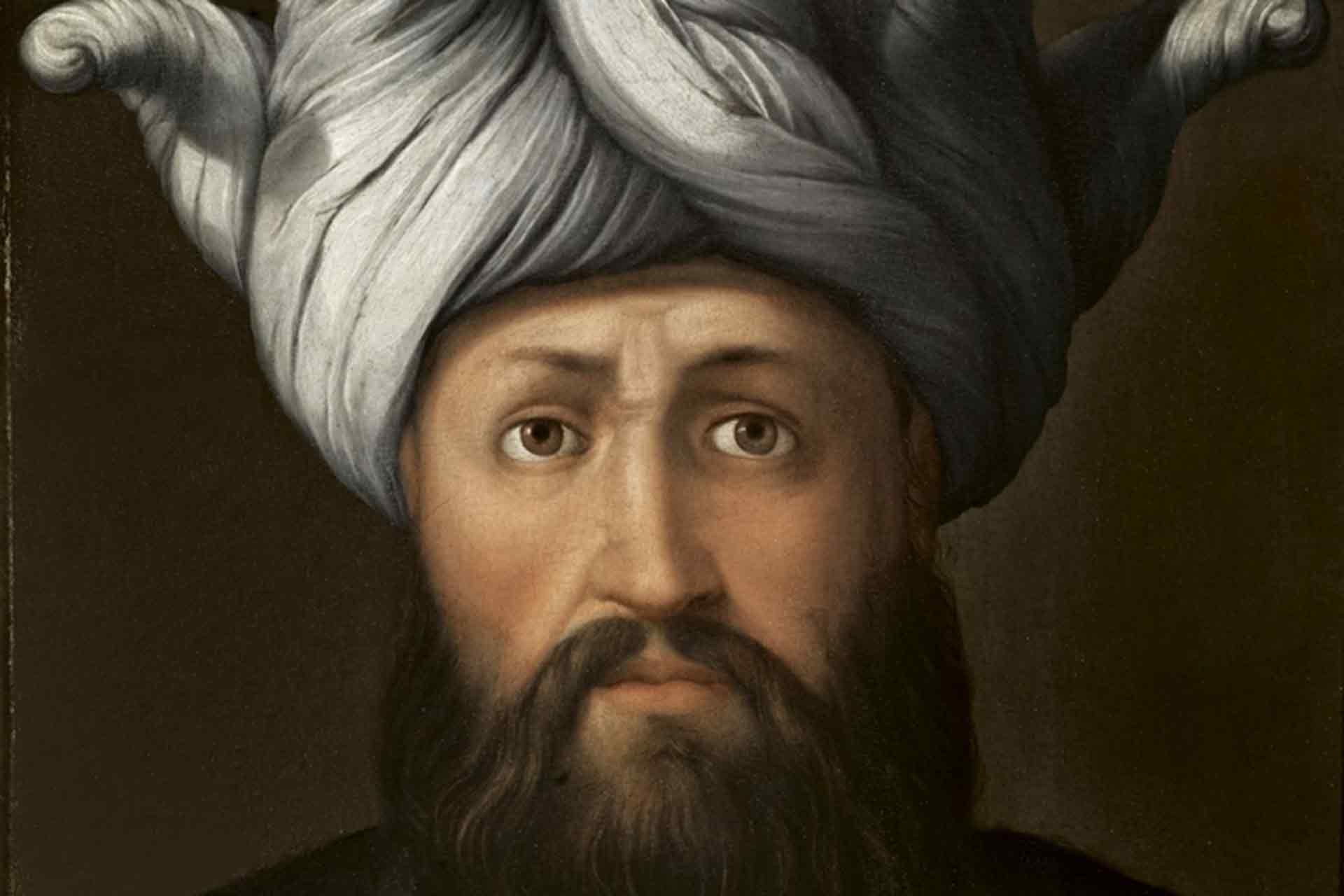

Saladin: The Warrior Who United the Islamic World Against the Crusaders

In the turbulence of the 12th century, when long-running internecine rivalries and the Crusader states had greatly divided the Islamic world which still dominated much of the Levant, one man would eventually appear who was strong enough and gifted enough to reforge a unity of purpose. Saladin, the illustrious Yusuf ibn Ayyub, proved to be a military leader and a politician who could heal the great schism between different Muslim groups. For these reasons, he remains a respected figure in Islamic history and Western accounts of the Crusades, in which he is portrayed, rather unusually, as both an effective enemy and a chivalrous figure.

Saladin’s impact on history was compounded by the fact that, at this time in the Second Crusade, foreign armies were menacing the holiest sites of Islam. Consequently, his campaigns against the Crusaders, culminating in the conquest of Jerusalem in 1187, had a significant effect on the balance of power in the Levant. But beyond this, his ability to forge a unified front from Cairo to Damascus and to reinvigorate a deeply divided Islamic world was Saladin’s fundamental distinction.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Saladin was born in Tikrit, on the Tigris River, in what is now Iraq, to a Kurdish family of military and administrative officers in 1137 or 1138. His father, Ayyub, was one of the army commanders under the Seljuk general Shirkuh. Saladin was a Kurdish Sunni, but he was placed in charge of a Shi’a-ruled state. Sectarian labels in the medieval Islamic world were complex and far more fluid than we might imagine.

Saladin’s first major military patron was his uncle Shirkuh, a leading military commander in the service of Nur al-Din, who ruled Syria and was also a determined opponent of the Crusaders. Saladin joined Shirkuh in a series of campaigns into Egypt, which was by this point in the hands of the Shi’a Fatimid Caliphate, but a state that was politically weakened by intrigue and factionalism at court. Saladin learned both the art of government and the art of war.

In 1169, the unexpected death of Shirkuh led to Saladin’s promotion to the position of vizier of Egypt, a crucial role in a politically charged court. He was just over thirty years of age when he was appointed, which came as a surprise to many. He was a Sunni Kurd in a leadership role in a Shi’a caliphate and initially did his best to keep a balance, ensuring that he was seen to be loyal to the Fatimid regime.

Saladin gradually brought the army and state under his control, working in the background to consolidate and promote the Sunni religious presence in Egypt. He appointed new administrators over the coming years, took control of the army, and formed alliances with leading political and tribal figures. In 1171, he effectively brought an end to the Fatimid Caliphate without bloodshed and publicly declared Egypt to be a part of the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate based in Baghdad.

Saladin’s political acumen and diplomacy were evident from an early stage and formed part of a larger picture. He sought the religious and political unification of the Muslim world to defeat an external enemy, a moral and religious framing that would characterize his rule for decades to come.

Unifying Egypt and Syria

The peaceful end to the Fatimid Caliphate in 1171 allowed Saladin to make his own political move. He pledged allegiance to the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate, effectively integrating Egypt into the larger Sunni Islamic community. This act was received well among Sunni religious circles and helped Saladin position himself as a legitimate broker of power in the Islamic world. With Egypt’s wealth and administrative machinery under his control, Saladin was able to build a stronger military force and project his influence.

To solidify his rule, Saladin needed to take more than just military control of Egypt. He initiated administrative reforms, boosted the economy, and secured the loyalty of his officers. Saladin’s prudent governance transformed Egypt into a stable and prosperous base, endowed with abundant resources and a skilled workforce. His personal reputation for justice, fairness, and piety also helped him gain the support of both the elite and the common people.

The unification of Muslim-ruled Syria and Mesopotamia was Saladin’s next primary objective. The death of his former overlord, Nur al-Din, in 1174 had created a power vacuum in the region. Saladin entered Syria and took Damascus without bloodshed, using political maneuvering and his reputation for mercy to his advantage. He then embarked on a series of campaigns to bring other Syrian cities, such as Homs, Hama, and eventually Aleppo, under his control.

These conquests were not always straightforward or bloodless. Saladin faced challenges from other claimants to Nur al-Din’s territories and had to navigate complex political landscapes, tribal rivalries, and the fears of local leaders who were wary of losing their autonomy. In Aleppo, a key Sunni power center, the ruling family initially resisted Saladin’s authority. After a period of siege warfare and diplomatic maneuvering, Saladin eventually took the city.

The political unification of the Muslim world presented challenges both on and off the battlefield. Saladin realized that for the unity to be lasting, it had to be based on more than just military conquest; it also needed a shared religious vision and administrative integration.

Saladin’s Religious and Political Vision

Saladin’s religious vision, both a deeply personal element of his leadership and a political instrument, was expressed in terms of reasserting Sunni orthodoxy and unifying the Islamic world. He was an early figure in jihad’s evolution into a communal obligation and used this to justify his wars against the Crusaders as the Muslim community’s holy duty. The effectiveness of his calls to jihad cannot be separated from his religious and political successes, which rallied Muslims across factional and communal divisions, gaining him the support of both clerics and the general public, including religious scholars, tribal factions, and city dwellers.

His religious and military policies and practices were closely linked. Saladin took a keen interest in the affairs of the religious class, restoring and building mosques, madrasas, and religious infrastructure, and promoting Sunni legal and theological education, especially in Egypt, where Fatimid Shi’a influence had been strong. This emphasis on religious patronage was crucial to Saladin’s own image as a defender of Sunni Islam. S

Saladin’s court attracted leading scholars and jurists from across the Islamic world, helping to establish him as both a religious and a military leader. His religious policies and practices were not ends in themselves but were deeply connected to his political aims and were deliberately broad in their reach. Saladin tied his rule to the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, aligning himself with the center of religious and political gravity in the Muslim world, which gave him additional religious and political capital and made his appeal to distant Muslim rulers and publics more effective.

Saladin was a pious and deeply religious man, and jihad was a central concept in his religious, social, and military life. Nevertheless, he was also a political pragmatist and understood that ideological zeal had to be moderated by practical political concerns if he was to maintain internal stability and power. S

Saladin took a keen interest in the religious affairs of his realm. Still, he was also an effective political and fiscal manager, taking steps to improve tax collection and distribution, ensure consistent legal practice, and address injustices and inefficiencies in his government. He personally reviewed complaints about oppression and injustice. He was known to seek out corruption in his administration, a practice that served both his political and religious interests.

Saladin’s personal religious convictions did not lead him to excuse or promote unbridled violence. While he could be ruthless and pragmatic, he also respected the value of diplomacy and negotiations when they served his purposes. He was known for his humane and merciful treatment of prisoners and civilians, both before and after battles. In doing so, he both set an example of ethical conduct for his followers and helped to solidify his positive reputation and legacy among both his contemporaries and those who followed.

The Crusader Conflict and the Battle of Hattin

By the end of the 12th century, the Crusader states, mainly the Kingdom of Jerusalem, had established a foothold in the Levant. Conquered by the First Crusade, they had been maintained through waves of pilgrims and crusaders from Europe. Lacking a substantial unity of purpose among themselves and support from the West, the Latin Christian states were struggling to maintain their presence in the Holy Land. As Saladin had unified most of the Muslim opposition in Egypt and Syria, his next target became the Crusader states.

The 1180s witnessed increasing hostilities between the Kingdom of Jerusalem and various Muslim forces in the region, particularly in Transjordan. This was primarily due to the conduct of Reynald of Châtillon, a Crusader lord with strongholds in the area of Kerak. He broke truces with Saladin, raided Muslim caravans, and even tried to attack Mecca and Medina, reportedly setting out to attack the city while carrying Saladin’s sister on his way back from a raid.

His efforts, for which he often did not receive the king’s blessing, gave Saladin both the cause and the public support to declare jihad against the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

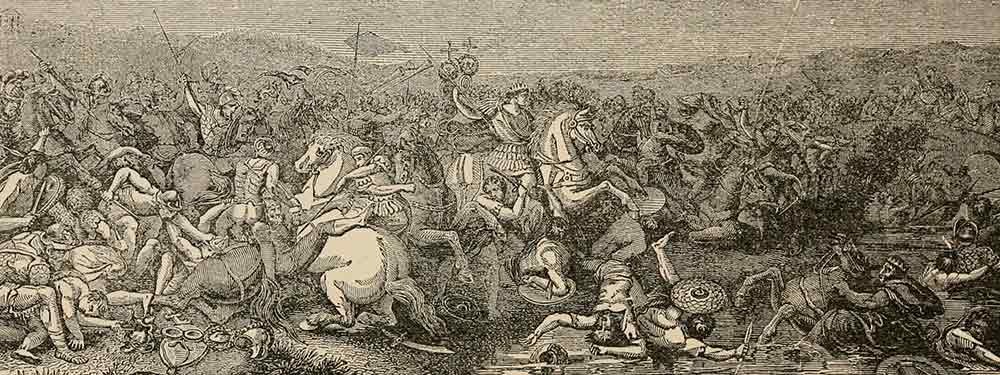

In the summer of 1187, Saladin set out to crush the Crusader army, gathering forces from across the Muslim world, including Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, Yemen, and the Hejaz. With most of his army, he besieged the city of Tiberias, where the wife of Count Raymond III of Tripoli was being held, baiting the Crusaders to come to her aid and engage his forces in battle.

A combination of extremist views from Reynald, the Templars, and other zealots, who convinced the more moderate Count Raymond III and Patriarch Heraclius to attack, and the delusions of King Guy of Lusignan, who also joined the march, led to the entire Crusader army leaving Tiberias and marching across the dry plains near the Horns of Hattin, west of the Sea of Galilee, straight towards Saladin and his army.

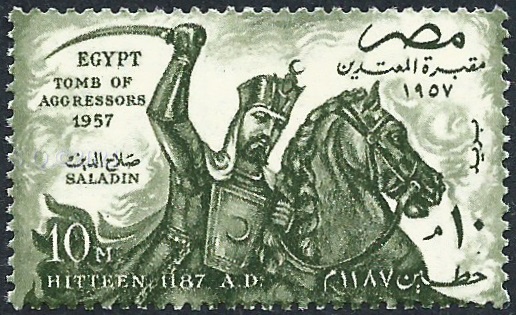

On July 4, 1187, the Battle of Hattin began. Saladin’s men surrounded the tired, thirsty, and marching without sufficient water in the morning heat, Crusaders on the battlefield and then proceeded to cut them apart. Using smoke from brushfires to demoralize the army, Saladin’s troops routed them, and the now retreating Crusaders were crushed. Saladin’s men took thousands of prisoners, and King Guy of Lusignan was captured but released later. Reynald of Châtillon was killed by Saladin himself, who said before executing him: “Twice you swore oaths by your religion, and twice you broke them.”

The battle was one of the most significant in the history of the Crusades. With their army annihilated, most of their forces were taken prisoner or fled the field, and their leaders either executed or captured, the Latin states were defenseless, and Saladin was free to move against them. He did so, and one fortress after another was captured across the Levant. With each conquest, his momentum grew, and he fell cities with little resistance.

In less than three months, he was before the walls of Jerusalem. While some of his men called for a massacre in retaliation for the First Crusade’s conquest, Saladin instead sought to take the city through negotiation. On October 2, 1187, the city capitulated after a brief siege, marking the end of nearly 90 years of Crusader rule in the Holy Land.

Saladin allowed most of its Christian inhabitants to ransom themselves and their families, and his men did not rampage the city. Churches were respected, and the Dome of the Rock, previously taken by the Crusaders and repurposed into a church, was rededicated as a shrine for Muslims. Saladin’s chivalry was in stark contrast to what had happened 88 years ago when the Crusaders took Jerusalem in 1099. Even Christian sources, such as William of Tyre, recognized his clemency and honorable nature. The fall of Jerusalem sent shockwaves through Europe, leading to the proclamation of the Third Crusade, and also began the legend of Saladin in both the West and the Islamic world.

Saladin’s leadership of his people, his military acumen, and political skills were critical throughout the conflict. The Battle of Hattin was the culmination of these qualities, as he outmaneuvered and then decisively defeated an enemy that was nearly 15 years before thought to be unbeatable. It was not just a military victory for him, though, as the success at Hattin also represented the victory for his efforts to unify the Muslim peoples under one banner, one that could fight against those in the Holy Land.

Legacy of Chivalry and Statesmanship

Saladin’s response to the Crusaders was characterised by restraint, particularly in his treatment of prisoners and conquered peoples. After the conquest of Jerusalem in 1187, he allowed Christian citizens to pay a ransom instead of being slaughtered or enslaved. He released many more who were unable to afford the payment at the behest of his wife and family members. His clemency in the face of the atrocity committed during the First Crusade made him one of the most admirable examples of mercy in the history of medieval warfare.

His benevolence, when juxtaposed with the intolerance and violence of his enemies, won him acclaim in his own community as well as the grudging respect of some Christian chroniclers. Medieval historians, such as Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad, described Saladin as a generous, pious, and devout Muslim. Their assessments were reiterated by some of his European contemporaries, including Ernoul, and later by historians like Steven Runciman. “A prince without fault,” wrote one European chronicler, “so generous that he gave away his fortune and died with nothing.” Saladin set the standard for justice and chivalry that other rulers aspired to, even as he diverged from their behaviour on the battlefield.

In the course of the Third Crusade, Saladin met, figuratively at least, Richard the Lionheart. The two leaders fought each other at several pivotal battles, most notably at Arsuf in 1191. But even as they struggled over the Holy Land, they came to respect each other enough to begin a series of diplomatic correspondences. Saladin sent fresh fruit and snow to Richard when the English king was suffering from a fever. On one occasion, he offered his own physician. The terms they eventually agreed on in 1192 gave Christian pilgrims the right to visit Jerusalem, though the city was not returned to them.

The legacy of Saladin is not only that of a military leader, but also a skilled diplomat and strategist. He was able to understand the politics of the Islamic world, unifying it through war and trust, while also making compromises and uniting his followers with shared religious values. Similarly, his negotiations with the Christian forces were motivated as much by pragmatism as by religious fervor. The truce he brokered with Richard on the shores of the Mediterranean remained in force for years to come, bringing temporary peace to the region and establishing Saladin’s long-term vision as a ruler who was able to strike a balance between faith and diplomacy.

Saladin died at 55 in 1193 and, despite ruling over an expansive empire, had next to nothing in the way of personal wealth. He was said to have so little in his treasury at the time of his death that there was barely enough to pay for his funeral. He is buried in Damascus in a modest tomb, with the epitaph: “Here lies the servant of God.” His final days and last will were marked by the same humility he displayed throughout his life, in the service of a cause greater than himself.

Over the centuries, Saladin has come to represent a variety of ideals, including Islamic unity and moral as well as military leadership. For Muslims, he is the man who freed Jerusalem and protected the faith. To many in the West, he remains an emblem of chivalry, a noble enemy who earned a degree of respect that transcended cultural and religious boundaries. The 12th-century military leader is immortalized not only in historical records but also in literature, folklore, and even diplomacy, as a fighter who battled ferociously and honorably, and a ruler who valued peace when it could be achieved with dignity.

Saladin has set an example of leadership – one based on faith, discipline, and mercy – as well as a model of power that is not limited to conquest. As one of the few people of the Crusades who can command respect in both the East and the West, Saladin is also the rare ruler who could reconcile strength with justice, and victory with compassion.

Enduring Legacy of Saladin

Saladin’s legacy, however, was more than the sum of his military achievements. His enduring victory was the reunification of the divided Muslim world, comprising Egypt, Syria, and large parts of Mesopotamia, under the banner of justice, religious conviction, and the rejection of foreign rule. He created a united force through diplomacy, military prowess, and a genuine personal piety that was strong enough to retake Jerusalem. His success redefined Islamic power in the face of European Crusaders and established a precedent for future military campaigns. He also forged a new administrative structure in his government based on stability, religious tolerance, and reform. His achievements and reputation as a just leader have continued long after his passing.

Saladin has been held in high esteem by subsequent generations throughout the Islamic world, and beyond. He was known for his humility, statesmanship, and chivalrous qualities, which were perceived as an example of how a true noble should behave. He was seen as an honourable adversary by the Western chroniclers of his time, while to the Muslims, Saladin was a hero who united a region and the hearts of its people. In an age of brutality and bloodshed, Saladin would rise above. He did not just reshape medieval history but redefined the moral expectations of leaders.