Spartacus’ Revolt: The Slave Who Defied Rome

Spartacus, the Thracian gladiator and revolutionary, has long been etched in the annals of history as a symbol of defiance and a challenge to authority. Once a slave, trained to entertain and fight for the amusement of Roman spectators, Spartacus would rise to become the leader of one of the largest slave rebellions in the ancient world. His name, a byword for fear among the Roman elites of his time, continues to reverberate through history as a testament to the indomitable spirit of resistance.

The Third Servile War, as history would record it, spanned from 73 to 71 BC, ignited by a handful of gladiators breaking free from a training school in Capua. Led by Spartacus, this small band of fugitives swelled into an army numbering in the tens of thousands. It was more than a mere rebellion; it was a movement that laid bare the vulnerabilities of Rome’s control and the desperation of those in chains.

Who Was Spartacus?

Spartacus was born in Thrace, a wild, mountainous region that is part of modern-day Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey. Thrace was home to many warrior tribes, some of whom served in the Roman auxiliary forces. Spartacus is thought to have been a Roman soldier at some point before he deserted. Sources such as Appian and Plutarch indicate that he was enslaved after rebelling against the Roman authorities. As a slave, he was thrust into the brutal world of the gladiator.

After his capture, Spartacus was sold to a gladiator school in Capua as part of the Ludus. The schools were run by lanistae, or gladiator masters, who taught enslaved men how to fight for the entertainment of the Roman people. Life as a gladiator was grueling, with brutal physical training, harsh discipline, and a regular chance of being killed in the arena. Spartacus, a hardened Thracian warrior, stood out quickly for his strength, discipline, and potential as a leader.

Amid the brutality and fear of the Ludus, Spartacus is said to have distinguished himself from the other gladiators. In addition to his physical prowess, he had a keen intelligence and a strong sense of justice. The ancient historian Plutarch described him as “more of a Greek than his countrymen in spirit and gentleness”, suggesting that Spartacus had a unique combination of physical and charismatic qualities. These traits made him a natural leader, and he quickly won the respect of the other enslaved men in the school, many of whom would become his closest allies in the rebellion.

His time in Capua gave Spartacus a first-hand look at the inhumanity of Roman slavery. Gladiators were some of the most well-fed and well-trained slaves in Rome, but they were still considered property, meant to die for the amusement of the masses. In the cruel world of the Ludus, Spartacus found common cause with the other fighters, men who were also desperate for freedom. In this crucible of violence and desperation, Spartacus and his allies began to hatch a plan to escape, setting the stage for the most famous slave revolt in history.

The Outbreak of the Revolt

In 73 BC, Spartacus, along with about 70 to 80 other gladiators, escaped from the gladiator school in Capua. Initially equipped with kitchen implements and makeshift weapons, the escapees overwhelmed their guards and fled. Historical accounts, particularly those of Plutarch, note that they found a cartload of gladiatorial arms, which they then used to arm themselves for a proper rebellion.

Escaping to the base of Mount Vesuvius, Spartacus and his followers used the terrain to fortify their position. The Roman response was initially to send a militia force led by Praetor Gaius Claudius Glaber. Glaber’s troops managed to surround the mountain, but Spartacus and his men ingeniously scaled down using vines as ropes and surprised the Romans, who were unprepared for such a bold move.

This early success in battle elevated Spartacus’s status among the slaves and emboldened more to join the cause. Ancient texts estimate that within a few months, Spartacus’s army grew to over 10,000 individuals, mainly composed of runaway slaves seeking freedom. The revolt began to adopt a more organized, strategic approach with each battle won.

Spartacus’s strategic acumen enabled his less experienced forces to outmaneuver Roman commanders. By leading raids on Roman settlements and agricultural estates, Spartacus’s forces not only liberated more slaves but also looted supplies. The Roman Senate, which had previously been somewhat dismissive of the threat, was forced to take more drastic measures as the rebellion spread through southern Italy.

The capacity of Spartacus and his followers to defy Roman authority in this manner was both shocking and revealing to the Roman Republic. The initial success of the revolt highlighted Rome’s vulnerabilities, particularly the over-reliance on slaves and the fragility of local military resources in the region. As Spartacus led his army with increasing confidence, what had begun as an attempt at self-preservation morphed into a fight for broader justice and autonomy.

By the conclusion of the first year, Spartacus’s rebellion had expanded in scale and impact far beyond what either the rebels or the Roman state had anticipated. His ability to rally, organize, and lead his followers to victory against trained Roman legions marked a significant turning point in the Roman perception of internal threats. The revolt was now a war, one that required all the resources and attention of the Roman Republic.

The Expansion of the Rebel Army

Spartacus’ cause attracted a significant number of supporters, bolstering his forces. At the height of the rebellion, his army numbered up to 70,000 men. Slaves from all over Italy had fled their masters to join the gladiator. A large portion of Spartacus’ army came from the countryside, and his followers were a diverse mix of individuals. Many of them were agricultural workers or former soldiers, providing a certain level of practicality and combat experience to the rebel army.

The rebel army had a remarkable structure for what was essentially a force of fugitive slaves. Spartacus divided his army into groups of 300, each overseen by his subordinates, such as Crixus and Oenomaus. It is important to note that this was not a force of unruly men running amok. Spartacus maintained discipline, and the rebels were not a disorganized rabble but a semi-professional army.

As with so many other aspects of the Third Servile War, it was remarkable how an escaped slave could organize such a force and bring men to heel. However, Spartacus had shown not only the ability to lead men into battle but also to conduct successful campaigns. He tactically avoided facing large and professional Roman armies on open ground; instead, he would attack Roman supply trains and patrols by surprise. Raiding convoys and then slipping away into the mountainous countryside was a style of hit-and-run guerrilla warfare that was highly effective in swelling his army with men who saw Spartacus as the new hope for slaves throughout the Roman Republic.

At other times, Spartacus demonstrated the ability to conduct successful, decisive battlefield strategies. In 72 BC, Spartacus defeated two separate Roman armies on different occasions; the armies were led by the consuls Lucius Gellius and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus. The Roman defeat at the hands of the slave army was particularly severe. Spartacus’ men isolated the two Roman forces and overwhelmed them in separate clashes. Many thousands of Roman soldiers were killed, and the survivors were forced to retreat to the city of Rome itself. The Senate was embarrassed by the defeat, and the Roman people feared the thought of Spartacus and his slave army marching on the city itself.

The historian Appian claims that, encouraged by their commander, Spartacus’s army considered marching on Rome after their victory over Lentulus. However, it is not certain whether this was indeed the case. The option was likely considered, as the defeat of Lentulus’ army would have given Spartacus enough manpower and resources to mount an assault on Rome. However, Spartacus ultimately decided against attacking the city, most likely because his troops lacked proper military equipment and were untrained.

His forces ravaged large parts of southern and central Italy, engaging Roman troops and marching on cities such as Nola and Metapontum. Large numbers of slaves were defecting to Spartacus’s army as news of his victories spread. Still, it was the invasion of Campania that really drove home the point that Spartacus was no longer a bandit or a gladiator. The slave had gone from being a local threat to the leader of an entire rebellion against Rome.

Spartacus’ actions had now made it clear that he was not only a gladiator leader. He was the head of a slave rebellion, and his rebellion had now reached the heart of the Roman Republic. With each battle and skirmish, more and more men were joining the ranks of the rebel army, swelling the already large numbers of Spartacus’ followers. Each of Spartacus’ victories further strengthened his position. By the end of 72 BC, Spartacus had grown his army in size and shown that the Roman system of slavery could be overcome with will and determination.

The Strategy and Goals of Spartacus

As for Spartacus’ long-term goals, sources diverge. Some ancient historians (for example, Plutarch) have argued that Spartacus sought freedom for himself and his followers, and their actions at the start of the rebellion support this view. The early stages of the rebel army’s movements strongly suggest a desire to leave Italy, marching north through central Italy towards the Alps, beyond which former slaves could disperse and attempt to return to their homelands. On the other hand, the continued size and momentum of the slave revolt have led some to ascribe to Spartacus more revolutionary aims, perhaps a desire to end Roman domination over the Italian peninsula.

In the winter of 73–72 BC, the rebels led their forces north again, intending to escape over the Alps and into Gaul. Heavily outnumbering their Roman opponents, Spartacus and his army seem to have set out deliberately to break out of the Italian peninsula and avoid further conflict with Rome. It made good sense, too. His army was not equipped for prolonged fighting and was growing increasingly ragged under the pressure of the Roman forces.

Spartacus’ repeated attempts to break out of Italy towards his native Cappadocia suggest that he planned on disbanding his army after crossing the Alps. However, even after reaching the northern part of the Italian peninsula, Spartacus inexplicably reversed course and began to march his army back south. This is one of the great puzzles of his career, as the army would have been only too happy to disperse as he had intended. An uprising in the slave ranks, or a renewed hope of victory, may have been factors in this decision.

In any case, the leadership of Spartacus and his allies was not united and, for a time, Crixus was in open revolt. The historian Diodorus Siculus (as well as a fragment of Livy) reported that at this time the rebel army was divided into two, with the larger half under Spartacus and the other under Crixus. Crixus and his men are thought to have been defeated at an unidentified battle by Lucius Clodius Glaber, commander of an eight-cohort force.

Crixus’ defeat probably influenced Spartacus to change his previous plans and move south instead of heading towards the Alps. The division of the slave army into Spartacus’ and Crixus’ forces may have resulted from disagreement about what to do next. It would be natural for the men who had joined the army from deep within Italy to want to flee the country, while those from the coastal regions may have wanted to stay and fight.

Either way, a revolt from within the slave ranks may have been a factor in this decision.The rebellion continued into 72 BC, and Spartacus once again tried to establish a more permanent base of operations. He looted several Roman cities in southern Italy, and established several stockades in the hills of southern Italy.

Roman Response and Military Campaigns

At the outset of the revolt, Roman authorities underestimated the scale and determination of the uprising. The Senate initially dispatched local militias and small detachments to quash the gladiators, expecting a swift victory. These forces were ill-prepared and suffered humiliating defeats from Spartacus’s disciplined and highly mobile army. Rome’s complacency soon gave way to alarm as the rebellion spread and challenged Roman authority in multiple provinces.

Recognizing the severity of the crisis, the Senate appointed Marcus Licinius Crassus to lead a renewed and concentrated campaign against Spartacus. A wealthy patrician with political ambition, Crassus viewed the task as an opportunity to elevate his reputation. He restructured the Roman legions under his command, instituting strict discipline, including the rare and brutal punishment of decimation for cowardice. This reinvigorated the Roman forces and signaled to the Senate and the rebels that Rome was fully committed to ending the uprising.

The Roman response to the revolt was initially tepid and ineffective, betraying a degree of complacency in underestimating the gladiators’ capabilities and resolve. Local militias and small military units were sent to hunt down the gladiators. Still, their lack of preparation and experience led to a series of embarrassing defeats at the hands of Spartacus and his disciplined, mobile forces. The situation became a crisis as the rebellion grew in size and audacity, with the rebel forces challenging Roman authority not just in Italy but across multiple provinces.

The Senate, recognizing the threat to Roman order and prestige, responded by placing the entire campaign under the command of Marcus Licinius Crassus, a wealthy and politically ambitious patrician. Crassus seized the opportunity to suppress the revolt as a chance to win glory and improve his standing in Rome. He reorganized and reinforced his legions with fresh recruits and imposed strict discipline, going so far as to execute by decimation—though this was rare and brutal punishment for cowardice—any soldiers who shirked from the fight. The reformed Roman army, galvanized by Crassus’s stern leadership, served as a declaration to both the Senate and the rebels that Rome would not take this uprising lightly.

Crassus also employed more effective strategies to contain the rebels, including cutting off escape routes and trapping them in unfavorable terrain. He avoided chasing Spartacus across rugged terrain and, instead, focused on building a series of fortifications to contain the movements of the rebel army. In one of his most brilliant tactical moves, he sealed the isthmus of Rhegium, a narrow neck of land in southern Italy, with a great ditch and wall. This maneuver effectively trapped Spartacus and his followers in a small area, cutting off their supplies and avenues of escape and subjecting them to a siege.

The battle-hardened and resourceful Spartacus and his followers launched several breakout attempts and defeated Roman forces in several pitched battles. At one point, Spartacus and his army even managed to breach Crassus’s fortifications, prompting another confrontation with the Roman troops. The tables had turned, however, and the once-mighty rebel army was now spent, fractured, and surrounded. The battle-weary rebels began to disintegrate, with Spartacus’s leadership under increasing strain as food shortages and the pressure of Roman military tactics took their toll.

Crassus eventually regrouped and started defeating the rebels in more minor engagements, steadily regaining the upper hand. The gladiator army was whittled down and scattered, and by the spring of 71 BC, a demoralized and weakened Spartacus’s army prepared for one final, decisive battle against the might of Rome’s reformed and reinforced legions. The Roman response, though initially slow and inadequate, ultimately proved overwhelming. Crassus’s campaign, with its harsh discipline and strategic acumen, quashed the gladiators’ rebellion, restoring Roman order and authority. The fear and embarrassment the rebellion had caused the Republic would ensure that Spartacus’s name would never be forgotten.

The Final Stand and Death of Spartacus

As Roman pressure on the slaves intensified, Spartacus needed to devise a new plan to save his army and regain the initiative. His latest idea was to escape to Sicily by negotiating with Cilician pirates. The plan was to use their ships to cross the Strait of Messina and incite a slave revolt on the island, opening a new front in the conflict. However, the pirates betrayed Spartacus, stole his money, and left him stranded. Without ships and with the Romans on his tail, Spartacus was forced to retreat into the mainland, his dreams of Sicily shattered.

Crassus used the failed Sicilian gambit to his advantage, stepping up his efforts to crush Spartacus. He trapped the rebel army in southern Italy and began constructing fortifications to cut off escape routes, slowly tightening the noose. Cut off from supplies and reinforcements, the once-united slave army began to break apart. Infighting and disagreements over their next move led to factions breaking away, only to be captured and executed by Roman legions. Spartacus himself refused to surrender and instead chose to fight to the bitter end.

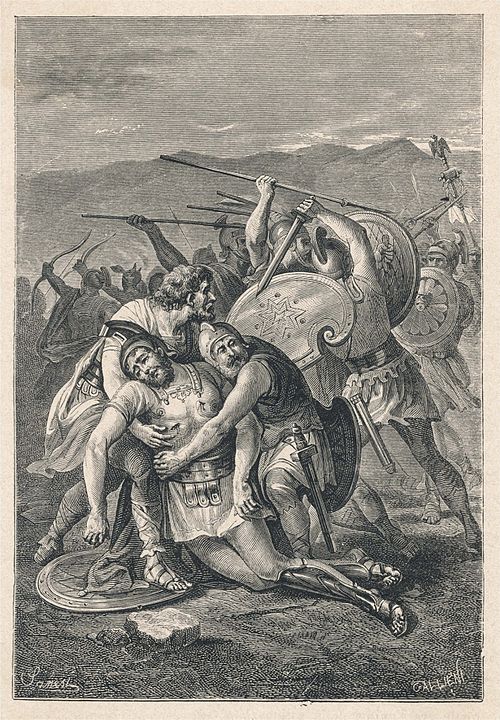

The showdown between Spartacus and Crassus took place in 71 BC near the river Silarus in the region of Lucania. Despite being outnumbered and outmatched, the legendary warrior is said to have put up a heroic fight. According to some sources, Spartacus cut a bloody path through the Roman ranks, hacking his way towards Crassus in a last-ditch effort to turn the tide.

Ancient historians like Plutarch and Appian described his last stand as one of ferocity and desperation, fighting with such intensity that he reached the general before being cut down. The exact circumstances of his death remain the subject of speculation, but it is generally agreed that Spartacus was killed in the heat of battle, surrounded by Roman soldiers. After the fighting, the battlefield was a gruesome sight, littered with the bodies of thousands of slain slaves.

Spartacus’s body was never positively identified among the slain, and his ultimate fate became the stuff of legend. His death symbolically ended the revolt, although small bands of survivors were hunted down in the following weeks. Spartacus’s final stand may have failed, but his name would live on as one of the most famous and revered rebels in history.

Aftermath and Legacy

The memory of Spartacus and his defeat in 71 BC weighed heavily on Roman minds. While the suppression of the rebellion reestablished the Roman order, the magnitude and persistence of the slave uprising shocked the Roman Senate. It exposed vulnerabilities in the empire’s heavy reliance on slave labor and illuminated the simmering unrest in its far-flung provinces. The crucifixion of the 6,000 captured rebels along the Appian Way was an act of gruesome deterrence as much as it was retribution. In an attempt to erase the uprising’s memory, the bodies of Spartacus’s followers were left to decay on the site of the triumph, and no record of his revolt was documented until over a century later.

The burning question in Rome following the conflict’s resolution, which also colored the historical record, was how such an extensive, seemingly existential threat to Rome could have occurred at all. Even as it demonstrated Rome’s military might, the rebellion forced the Romans to reexamine their army’s preparedness, the social injustices that gave rise to such uprisings, and the need for more responsible governance over the provinces.

In Roman historical literature, Spartacus was a figure of fear and grudging admiration. Accounts by historians such as Plutarch and Appian depicted a brave and cunning leader whose tactical acumen was on par with Rome’s most celebrated generals. As centuries passed, his image evolved and was colored by the lenses of the time. In modern times, particularly during the revolutionary fervor of the 18th and 19th centuries, Spartacus was romanticized as a champion of the oppressed against tyranny. Karl Marx famously dubbed him “the finest fellow in ancient history,” and revolutionaries across Europe harnessed his name as a rallying cry for justice and liberation.

In the contemporary era, Spartacus’s legacy transcends the bounds of history, becoming a cultural icon. His life and revolt have been the subjects of books, films, and political discourse, and his story endures as a powerful narrative about the indomitable human spirit’s fight for dignity and freedom. From a Thracian slave who challenged an empire, Spartacus has become an emblem of resistance and the eternal quest for liberty.