The Albigensian Crusade: How Rome Tried to Erase the Cathars

The Albigensian Crusade was launched in an Occitan region at peace and on the economic rise. The tolerant region of Languedoc, its thriving towns, and poets became a source of anxiety for Rome as Catharism took hold among the population. The dualist faith, which emphasized the material corruption of the world and the unreliability of Church authorities, threatened to upend Rome’s influence over communities in southern France. For the leadership of the Catholic Church, the movement’s alternative form of Christianity and rejection of materiality warranted the Church’s increasing fear, which justified a crusade unlike those fought in the Holy Land, one fought in Europe against Europeans.

The results of the Albigensian Crusade were a bloodier chapter in Church history than any inquisition or in-fighting, as the political, military, and ideological force of the Catholic Church razed towns and brought war to Occitania. The papacy, northern French nobility, and the monarchy used the crusade to impose their power, bringing to an end the independent region, its autonomous religious culture, and resulting in near-total silence on the Cathars and their history.

Origins of the Cathar Movement

Medieval Languedoc was a particularly hospitable environment for heretical ideas. The region was one of the most prosperous in Europe at the time, with busy towns, bustling trade routes, and a vibrant tradition of urban self-government. These factors led to a society in which feudal magnates did not have the same degree of influence as in northern France. In the south of the country, Occitania was known for its cultural tolerance, with Jewish communities, merchants, troubadours, and clergy living in proximity to one another.

In such a society, unusual ideas spread easily, and, as one chronicler wrote, Languedoc was “where every man spoke his mind.” In this way, the region was significantly more open to spiritual exploration and deviation than other parts of Europe.

It was in this environment that the Cathar movement developed, becoming a significant alternative to the Church’s teachings. Cathars were adherents of a Christian dualist belief system which posited that the universe was a battleground between the forces of light and darkness, with the material world being equated with evil.

]The most committed of them were known as the Perfecti and rejected material wealth and violence, following an austere lifestyle. The humility and self-discipline of the Cathars won them the support of many laypeople, both among the peasantry and among the nobility. In a region where resentment of clerical wealth was high, the Cathar movement seemed to many to be a purer, more authentic form of Christianity than the one offered by the Church.

The movement had a significant impact on medieval Christianity in Languedoc by rejecting material wealth and the idea of a physical church hierarchy. The Cathars did not recognize the sacraments of the Church, such as baptism and the Eucharist, and argued that there was no need for a priestly class to mediate between the believer and God. This denial of the Catholic priesthood and sacraments was a direct challenge to the authority of the Church.

The movement’s success in attracting adherents among the local nobility and the urban elites of towns such as Toulouse and Albi was also seen as a threat to the papacy’s power. In a region already known for its cultural independence and defiance of authority, the influence of the Cathars was seen as a direct challenge to Rome.

By the late twelfth century, as the Cathar movement had taken root and spread throughout Languedoc, the Church came to see it as an existential threat to its authority in the region. Papal legates had been sent to the region to try to win converts away from Catharism, but met with limited success, especially where the local population was suspicious of wealthy, well-fed clergy.

The fear was that an entire region of Europe would be lost to the Church, and as the movement became more established, it was seen not only as a theological but also as a political problem. In the context of the wider conflicts of the period, this was a significant development with major consequences for the Church.

Tensions Build: Before the Crusade

In the years preceding the Albigensian Crusade, the Catholic Church had several opportunities to confront the Cathars by more peaceful means. It had also made several attempts to address the problem of Catharism in Languedoc before taking up arms against the sect. Missions from Cistercian monks were sent to southern France in a deliberate effort to win Cathar sympathizers through example.

Cloistered in their own communities and preaching humility and poverty, the monks initially found little success. They were regarded with suspicion by the local populace and, in the south, often as interlopers by the urban population. The Cathar Perfecti, with their own lives of actual poverty, usually made a more convincing impression than wealthy churchmen. Cathar and Catholic scholars were occasionally placed in the same towns to debate publicly. However, the Cathars were usually victorious in these debates, further tarnishing the church’s reputation.

This exasperated Pope Innocent III, who, like his predecessors, felt that at least persuasion should have succeeded if the clergy had lived by the rules of Christianity. He was scathing in his criticism of the local bishops, berating them for their moral laxity and negligence of their duties, and claimed that this was the reason why the Cathars’ attacks sounded so plausible. Further attempts were made to reform the local clergy, but progress was slow. In many towns, such as Albi and Toulouse, the Cathar preachers were backed by the urban elite, whose social position and strength grew rather than diminished as a result of the Church’s peaceful measures.

The early optimism of a peaceful conversion of Catharism was fast disappearing, and the thought of ridding Languedoc of heresy through negotiation was starting to seem both difficult and impossible.

Then, in 1208, all hope of a peaceful resolution was abandoned, and events hurried. Pierre de Castelnau, one of the two papal legates sent to the region to try and negotiate a solution, was murdered on the banks of the Rhône. Castelnau had been in the employ of the Church for several years and was, at the time of his death, attempting to deal with Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, who was accused of being too soft in his handling of the Cathars.

The relationship between the papal legate and Raymond had been on a downward trajectory. At their last meeting, the two had argued heatedly, and Castelnau, who was an astute politician, no doubt felt that the danger to him personally had increased. Castelnau left the meeting and was on horseback on the opposite bank of the river. His exact words at the time of his murder are lost, but it is known that he called out something against Raymond and his attendants before he was speared through the chest by an unknown assassin. He was killed on the field and never regained consciousness.

The identity of the killer was never established beyond all doubt, but there was a strong suspicion of Raymond VI and his immediate family, whether justified or not. Raymond certainly had both the opportunity and the motive for the murder. Innocent, however, never wavered in his belief that Raymond was guilty, and in 1209, Raymond was excommunicated on the pretext of the murder.

The murder of the papal legate was the signal for Innocent III to act. In a letter, he described the murder as an assault on the Church, and the preparations for war began. With the murder of Castelnau, he was able to frame a letter to the French nobility, announcing a crusade against the heretics of Languedoc and promising complete forgiveness of sin for those who took up arms. The response of the pope and his cardinals, as described by the chronicles of the time, was immediate. Within months, the first crusading forces began to gather on the borders of Languedoc, and war seemed inevitable.

Launching the Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade

Innocent’s call for a crusade was a dramatic shift in policy toward the Cathars and their supporters. While other crusades had been directed at pagans or Muslims outside Christendom, the campaign in Languedoc was against other Europeans. Innocent portrayed the war as a sacred duty required to protect the Church, and argued that heresy was an internal danger far worse than external enemies.

He offered full indulgences to anyone taking part in the recruitment effort to attract as many participants as possible, promising the same spiritual rewards as those granted to those going to Jerusalem. The pope also authorized crusaders to retain rights to the land they conquered. He offered financial incentives for others to join, making the campaign a profitable venture for ambitious nobles or those facing financial difficulties.

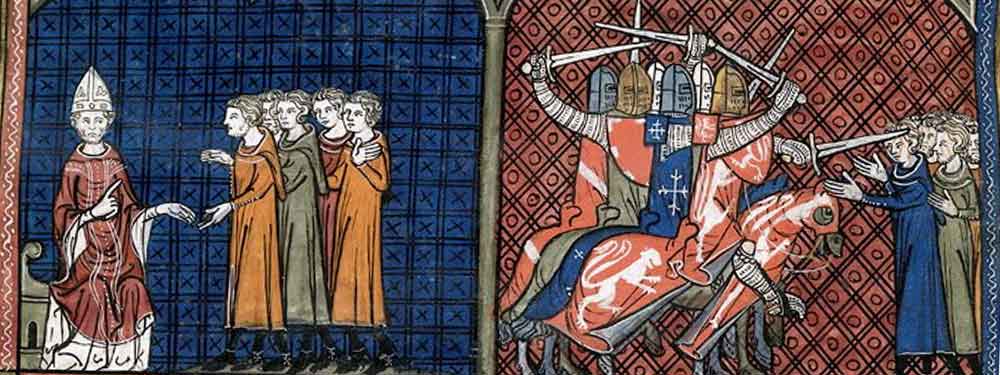

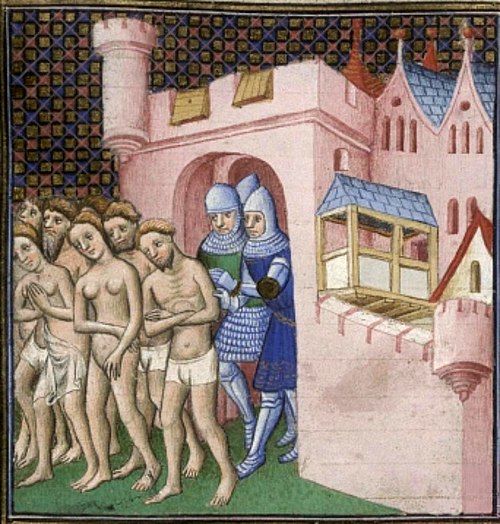

Massacre against the Cathars during the Albigensian Crusade (right)

News of the pope’s appeal spread quickly through northern France, where a great many noblemen were eager to take up the cross. Aristocratic families who were heavily in debt or had ambitions to expand their lands understood that the southern regions of Occitania were wealthy and fertile but also politically divided. Chroniclers at the time stated openly that many took up the cross because they could “win glory and territory under the cloak of religion.” The effects of these mixed motives would be felt in the coming years.

The northern armies assembled with very little concerted resistance from the local rulers in Languedoc. The lands of southern France were a collection of semi-independent fiefs, all owed a measure of loyalty to a regional overlord and, ultimately, to the French king. They were a loose collection of bishops, lords, and towns, each with its own traditions and practices. Some nobles had been vocal in their support for the Cathars, but most sought to distance themselves from heresy, hoping to avoid excommunication and punishment from the Church.

This lack of any centralized resistance made organized defense nearly impossible. The most powerful lord in the region, Raymond VI of Toulouse, wavered in his support for the Cathars and alternated between placating the papacy and supporting his local subjects. As a result, Occitania lacked a cohesive political front.

The crusading armies assembled in the north and prepared to invade southern France, meeting very little resistance. When they crossed the borders, they encountered a patchwork of poorly organized and unprepared defenses. Towns like Béziers and Carcassonne mobilized local militias and did what they could to prepare defenses in a short space of time. The papal promise of full indulgences from sin also ensured that the crusaders arrived in the south with high levels of motivation. This deeply religious conviction and the material incentives provided by the pope combined to form a force that was both zealous and opportunistic.

The Albigensian Crusade was now well underway, and the papacy had in many ways shifted its initial objective from eradicating heresy to territorial conquest. This effect on the balance of power in southern France would have long-lasting effects on the Languedoc region, and the fragmented nature of Occitan resistance meant that the crusading armies would strike hard and early in the war.

Year of Blood: Béziers and Carcassonne (1209)

The first target of the Albigensian Crusade was the city of Béziers, which fell in July 1209. The town’s inhabitants were asked to surrender all known Cathars, but refused, claiming that they would not turn in their neighbours or relatives. During the ensuing siege, a cry went up as the crusaders began their assault, “Kill them all; God will know His own.” This phrase was supposedly uttered by the papal legate, Arnaud Amalric. However, some sources suggest that it was misheard or mistranscribed, and it is unlikely that Amalric would have used such violent language in any case. However, he later wrote that “neither age nor sex was spared,” so the extent of the massacre is not in doubt.

In the fighting that followed, Catholic and Cathar alike were killed indiscriminately. With fires consuming much of the city, thousands died in a few hours, until there was no one left to kill. Béziers was one of the wealthiest and most populous towns in Languedoc, but it was left a smouldering ruin, its streets empty and silent. The massacre sent shockwaves through Europe and was a warning to the other towns of the Occitan.

The Church, however, had no hesitation in presenting the fall of Béziers as a triumph for Christendom, the will of God made manifest. Occitans, on the other hand, knew that this was only the first taste of a campaign that would be bloody indeed. During the rest of 1209, the crusading army marched through Languedoc, tamping down Cathar resistance in the towns that it passed through.

The crusade then made for Carcassonne, another well-fortified city in the territory of Raymond-Roger Trencavel, viscount of Béziers. Trencavel had been given notice of the crusade’s advance by his vassal at Béziers and had prepared a defence, but the crusaders were far too numerous. They quickly invested in the city and brought up siege engines designed to starve it of food and water.

Carcassonne was large and prosperous, but there was nowhere for the citizens to flee during the siege. Summer was at its height, and the city was overcrowded with refugees, straining its resources and rationing food. Its wells were deep, but they ran dry within a few weeks, and men, women, and children alike were forced to drink from the rivers.

Carcassonne endured for several weeks, aided by defences among the best in Languedoc. Negotiations were attempted, and when Trencavel appeared in the crusader camp with safe conduct, he was seized and imprisoned. The garrison and people of Carcassonne were hard-pressed, but Trencavel’s men knew they could expect no mercy if the city was taken by storm. It was left to the leadership to decide the city’s fate, and they soon accepted that there was no other choice but to surrender. The Crusaders entered Carcassonne on August 1, 1209, but rather than being protected, the people were expelled by the conquerors. The city’s men, women, and children were driven from their homes with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

Carcassonne’s fall was another triumph for the crusaders and a personal blow to Raymond-Roger Trencavel, who died in prison under mysterious circumstances. Occitan political autonomy collapsed as the Crusaders placed their own men in the region’s castles and abbeys. The barons of Languedoc who had submitted had little to say in the matter and trebled their oaths of fealty, just to be safe.

Taken together, the slaughter at Béziers and the siege of Carcassonne showed both the strength of the crusade and its utter ruthlessness. The Crusaders were now in a position to advance through Languedoc, confident that the events of Béziers and Carcassonne cowed their opponents and that other towns would surrender rather than face the same fate.

The Rise of Simon de Montfort

In the wake of Carcassonne’s surrender, the crusading army fell under the command of Simon de Montfort, a veteran knight known for his strict discipline and pious fervor (not to be confused with his son, who led the Barons’ Revolt against Henry III). Montfort had made his name in previous campaigns, and his blend of martial prowess and religious zeal made him an attractive figure to the Church. Many northern knights who had joined the crusade in search of land or glory had little interest in long-term campaigning in Languedoc. De Montfort was different. He stepped up to the task with enthusiasm, ready to lead the campaign as the Church desired.

Contemporaries described de Montfort as “unyielding as iron,” a characterization which events were to prove dreadfully true. His approach to quelling resistance was often one of brute force. Montfort had a particular penchant for the strategy of forced conversion when taking towns. If the townspeople refused to renounce their Cathar faith, de Montfort did not hesitate to mete out executions.

It became common to see public burnings at the stake. Scores of Cathar Perfecti, lay believers, and their families would be tied to stakes and ceremoniously burnt alive in the town square. Chroniclers record de Montfort ordering mass executions without trial or following a perfunctory trial in one notable instance, emphasizing his view that the extermination of heresy required no mercy.

His skill at siege warfare was also notable. De Montfort captured several towns and castles that had long been Cathar bastions. Fortified towns like Minerve, Termes, and Lavaur fell to his armies, often after prolonged sieges or stubborn resistance. In 1211, the fall of Lavaur became one of the most notorious massacres of the crusade. After the town’s surrender, de Montfort had the lord of Lavaur hanged, imprisoned the lord’s wife in the town well until she died after several days, and burned more than 400 Cathar Perfecti and lay believers. Montfort’s actions at Lavaur and elsewhere earned him a reputation as the most ruthless commander of the crusade.

Each conquest saw de Montfort’s influence grow. He was granted the lands of vanquished lords by papal decree, turning him from a minor baron into a power in his own right. This rise in power was deeply concerning to many across Languedoc, including some who had previously sought conciliation with the Church. As more land fell into de Montfort’s hands, he grew more ruthless in his determination to stamp out the last of Catharism and any lingering resistance.

This was not without its cost. The brutality of de Montfort’s methods only stoked hatred and resistance among the Occitan populace. Even nobles who did not share the Cathar faith began to see de Montfort as a threat to their own autonomy and traditions. Resistance to his armies remained strong, yet he pressed on, driven by a sense of divine mission and papal support.

By the time of his most successful campaigns, Simon de Montfort had turned the Albigensian Crusade into a land grab, a political conquest of the region of Languedoc that was just as much about personal gain as it was religious cleansing. The rise of de Montfort marked the dark days of the war, when zeal and ambition exacted an unthinkable toll on the people and culture of the region.

Occitan Resistance and Shifting Power

The strengthening position of Simon de Montfort and the crusaders did not go unchallenged in the regions of Languedoc. Tensions were growing among the local nobility, who began to rally against the northern incursion with greater resolve. In Toulouse, a wealthy and independent city, the sentiment of resistance coalesced into a more organized form of defiance. Raymond VI of Toulouse, who had been widely accused of heresy and fostering Catharism, returned from his years of penance to gather support among the Occitan populace.

Alliances were brokered and reinforced with the local lords of the region, his son, Raymond VII, who were keen to resist the perceived northern aggression. The rebellious sentiment spread, and towns and cities across the region rose in revolt against the crusaders. Garrisons were driven out, and old allegiances were restored. The tide turned against the crusaders in 1218. During a siege of the city of Toulouse, Simon de Montfort was struck and killed by a stone from a defensive trebuchet. The incident was recorded as divine justice by many contemporary chronicles.

The death of Simon de Montfort was a significant turning point in the Albigensian Crusade. The crusading forces were left leaderless and without a commander of equal caliber to lead their efforts. De Montfort had been a particularly effective military leader, and his death led to a relative lack of momentum among the crusaders. His son, Amaury, took up his father’s campaign but lacked his decisive cruelty.

The Occitan nobility, who had lost ground in recent months, seized the opportunity to reclaim some of their lost influence. The local leaders began to regain confidence and made substantial inroads in the fight against the northern crusaders. The town of Toulouse, the center of this nascent Occitan resurgence, was itself a focal point of the shifting momentum. The city had borne the brunt of de Montfort’s initial success, but was now seen as a center of anti-crusader resistance and reorganization.

The success in Toulouse was not a decisive blow against the crusaders, however, and peace did not yet come to the region. The conflict in Languedoc continued for some time, broken into several more minor conflicts and skirmishes. The crusader forces were at a disadvantage after de Montfort’s death, as many of the northern lords were loath to give up the lands they had so recently seized. The Occitan forces also lacked the cohesion required to press the crusaders from the region.

The fighting continued for several years in a piecemeal fashion. Skirmishes, sieges, and reprisals were repeated across the lands of Languedoc, with the front lines in the region waxing and waning as various forces sought to press their claims against opponents in the name of the Albigensian Crusade.

The papacy repeatedly and significantly took an interest in the region, seeking to influence the course of the war in various directions. Innocent III, who had been the prominent figurehead of the crusade, died in 1216, but the crusade did not wane in its zeal after his death. His successors continued to advocate efforts to suppress heresy and heretics and, by extension, to increase the power of the Church in the region.

Papal legates were dispatched at various times and had the power to mediate, chastise, or support any of the rulers in the area, depending on political pressures. Papal attempts at mediation often resulted in a brief cessation of the fighting, though it was rare to see permanent peace brokered by papal edict. Papal involvement, however, ensured that the crusade remained both a spiritual and a political conflict, enmeshed in many territorial disputes with both secular and spiritual overtones.

The war, after many years of crusader invasions, had by then morphed into a power struggle between northern occupiers and a southern nobility weakened by several years of crusading. The Occitan resistance had won some important victories, but much of the political landscape had been redrawn, and the future of the lands of Languedoc was already changing. The French crown was growing ever more interested in bringing the prosperous region more fully under its control, and the collapse of the local lordships made this an easier task.

De Montfort’s death was a critical moment in the Albigensian Crusade. While it marked a turning point in the crusaders’ fortunes, it did not bring an immediate resolution to the conflict. The subsequent wars revealed both the long-term weakness of the region’s local rulers and the rising influence of the French crown. The Occitan resistance had slowed the crusade’s momentum, but the changing political landscape meant the fight over Languedoc’s identity and autonomy would not end with the crusade.

The Siege and Fall of Montségur (1243–1244)

Montségur dominated the Pyrenean foothills like an island unto itself: remote, heavily fortified, and brimming with spiritual significance. By the early 1240s, it was the last bastion of the Cathar Perfecti who, hounded by increasing persecution, had fled there in the hope of finding safety. The castle’s steep, almost vertical walls and commanding view made it one of the most naturally defensible strongholds in Languedoc.

Inside its walls, a small community of Cathar clergy, their families, local craftsmen, and soldier-freemen lived and worked in relative isolation. The daily routine during the siege was grim but highly disciplined, with time divided between shared prayer, mealtimes, and watching for attacks. Chroniclers writing after the fact often refer to Montségur as “a citadel of faith as much as stone.”

In May 1243, French royal forces, combined with local lords who were willing to swear fealty to the crown, surrounded the mountain and began a siege. The attackers constructed wooden barricades and siege platforms on the slopes of the surrounding peaks to batter the stronghold. Inside Montségur, the defenders hunkered down to face a long winter. They survived on meager rations, later described as salt fish, hard bread, and soups. Foraging parties ventured out under cover of darkness, but were often harassed by French troops.

Despite increasing persecution, the Perfecti continued to provide consolamentum (the unique sacrament of the Cathars) and to oversee Cathar rituals, offering spiritual consolation to the besieged. The community far outnumbered the garrison of fighters in the castle, and in many ways, it was Montségur’s natural defenses that held.

By early 1244, the defenders knew their situation was untenable. The besieging army had cut off every possible escape route. Negotiations opened, and the terms were offered: those who recanted their Cathar faith would be spared, but those who did not would be put to death. More than 200 Cathars, Perfecti, and believers both, elected to stand firm with their faith. They negotiated a two-week delay to allow for last rites and preparation.

On March 16, 1244, Montségur fell. At the base of the mountain, a huge wooden pyre was constructed. Accounts from the time record that over 200 Cathars voluntarily threw themselves into the flames, choosing death rather than surrender. None tried to rescue themselves, or even to escape. This single, mass execution would become one of the most famous and haunting moments of the entire crusade.

The fall of Montségur marked the symbolic end of organized Cathar resistance. While scattered holdouts and isolated believers survived in remote communities, the spiritual center of Catharism had been crushed. The destruction of the castle and the martyrdom of its inhabitants reverberated across Europe, sealing the fate of the religion that had once thrived in Languedoc’s towns and countryside.

To later generations, Montségur would become both a symbol of the tragedy of cultural and religious suppression and a potent emblem of the extraordinary will of a people who would not be denied the right to their own faith.

Over the centuries, the site took on a near-mythic status. To the Church, it served as proof of God’s triumph over heresy; to others, it would become a place of memory, a stark monument to a way of life which was now lost. The ashes of Montségur were the final, chilling chapter of the Albigensian Crusade.

Birth of the Medieval Inquisition

Military campaigns in Languedoc had primarily come to an end, but Rome had not abandoned its war on Catharism. Instead, it had begun to construct a more permanent mechanism of suppression, a Medieval Inquisition, which would systematically interrogate the population in search of heretics and their sympathizers. From the 1230s, the new institution developed a legal structure and methodology to control and repress Catharism: It would keep records of interrogations, employ a network of paid informants, and operate year-round instead of in occasional bursts. Inquisitors had the right to issue citations, question entire communities, and seize the property of anyone found guilty of heresy.

Over the course of decades, inquisitors—typically Dominican friars trained in theology and law—developed techniques of interrogation and confession to expose secretive networks of Cathar believers. Sessions could last from hours to days, depending on the obstinacy of the suspect, and individuals were typically required to report on all of their religious experiences, contacts, and conversations.

Torture was not initially common, but would become a legally sanctioned tool for eliciting confessions. Punishments for convicted Cathars included enforced penance or imprisonment, but also the handing over of heretics to secular authorities for execution by burning. Accounts of the Inquisition often mention dozens of burnings in a single day, highlighting how deeply the organization permeated local communities.

Property confiscation was another effective tool. The inquisition could, and often did, strip wealthy families of landholdings, vineyards, dowries, inheritances, or all of the above if they were suspected of harboring sympathies for Catharism. Inquisitors maintained an atmosphere of fear, and the knowledge that neighbors might denounce one another out of local feuds or personal grudges was often enough to elicit denunciations. Tensions of this sort reshaped villages, as relationships with even suspected heretics could earn a household a visit from inquisitors and possible imprisonment. Over time, such measures effectively suppressed what remained of local support for Cathar beliefs.

The long-term effects on the region were significant. Languedoc was rapidly losing the cultural and political characteristics that had distinguished it from the rest of the country. The decline of the Occitan language had only begun. Still, it was clearly accelerating: Royal administrators and church officials used northern French dialects in government and liturgy, which quickly took hold among the educated classes.

Many noble families had been dispossessed of their holdings, and so the influence of independent political power centers declined. Chroniclers writing as early as the mid-13th century would remark that “Languedoc is no longer its own”, and this assessment became increasingly true in the coming decades.

In addition to suppressing Catharism, the Inquisition also left behind a psychological legacy that would persist across generations. Communities became defined by suspicion, silence, and a self-censorship of their own traditions. Practices that had once been the source of local identity were now abandoned or driven underground, and the memory of the Cathars was preserved through whispered rumors or secret manuscripts. In this way, the Medieval Inquisition achieved not only the suppression of heresy but also the effective erasure of the cultural landscape that had enabled it

Aftermath and the Erasure of a People

The final defeat of the Cathars and the fall of Montségur marked not just a military victory but the beginning of Languedoc’s integration into the burgeoning French state. The Capetian kings, over the course of the 13th century, slowly reined in the powers once enjoyed by the local nobility and the Occitan culture. Agreements like the Treaty of Paris (1229) stripped local rulers of power and brought the land under northern control. With the influx of royal officials, taxes, and legal codes, Languedoc’s independent culture began to decline. Occitan institutions were stripped of power, those of the north replaced local customs, and by the 14th century, the region was no longer what it had once been.

The result was a place that was no longer free. The Occitan language slowly lost its prestige to the language of the north. The age of the troubadours was over, with themes of love and philosophical freedom now either censored or discouraged. The old days of urban independence and cultural pluralism were forgotten as the slow march toward a centralized French state continued. Chronicles at the end of the 13th century began to refer to “the land of the south” as if it were a foreign country, remarking that “the land of the south speaks with a new voice.”

Yet even as they were driven from public life, the Cathars would not disappear from memory. Over the next few centuries, legends began to build up around them and their fate. Medieval writers and the romantics that followed told stories of these enigmatic heretics, imagining them as spiritual seekers burned at the stake for their beliefs. Others spoke of secret rituals and hidden gospels, an ancient spirituality that would be carried on in secret.

By the 19th and 20th centuries, new myths and conspiracies would be added to the mix: that the Cathars had esoteric teachings that the Church feared, hidden gospels and sacred treasures spirited away from Montségur in the dead of night, knowledge handed down from the first Christian mystics.

To one degree or another, these stories have been discredited as historical fact. They have often been used to promote various new-age or new-age-inspired ideologies with scant factual basis. In one sense, these are just more conspiracy theories, added to a mountain of others in a world with little need for them.

But if there is a reason that these rumors have persisted, it is because there was something worth hiding. The carnage and destruction of the crusade, followed by the Inquisition’s later work, left behind a lasting impression that something had been lost. The story of Montségur itself fueled this suspicion, for pilgrims and other seekers have been visiting the site since its destruction, coming to the ruins to contemplate their own “esoteric truths” and to imagine that they too might be walking over secret knowledge, wisdom that had once been burned on this hilltop along with the Cathars.

Final Thoughts on the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade was one of the most important events of the Middle Ages, with far-reaching effects on religious life and on political and social structures in medieval Europe. The war, cloaked in the guise of a religious crusade to wipe out heresy, led to the practical and complete destruction of the Cathars, the reconquest of Languedoc by France, and the creation of the Medieval Inquisition.

It helped centralise power, unify the region under the crown, and transform its religious and political map. But more than that, this spiritual war was also a calculated act of genocide; a deliberate attempt to obliterate one of the most unique, creative, and open-minded cultures of Europe.

The ramifications of this were profound. The disappearance of Occitan tradition, the decline of the Occitan language, and a central spiritual paradigm of life in southern France devastated the region. The way the area and its cultural identity were changed was brutally efficient, leaving a scar on southern culture that is still felt today.

The downfall of the Cathar paradigm and the suppression of their culture were startling in their suddenness; just how rapidly the troubadour courts disappeared, and local power structures and autonomy were dismantled, is a large part of what remains so remarkable about the crusade. The example of the Albigensian Crusade is also instructive regarding the efficacy of ideology in the service of a political end; one man’s heresy is often the justification for decades of violence, forced conversion, and the breaking of a culture.

To this day, the Cathars are a sign of southern France, their memory standing as a metaphor for both their own persecution and their perseverance. They prompt us to question how short the period of religious tolerance and enlightenment can be, how vulnerable an entire population can be to the whims of the powerful, and how powerful the need for spiritual exploration and a desire to find alternative paths in life can be.

The story of the Cathars still lingers in the stones of Montségur, in inquisitorial records, in a range of legends that survive in Occitan folk culture, and of course in their recent memory, long after those who would have tried to wipe them from history have themselves become dust.