The Battle of Culloden: A Turning Point in British and Scottish History

On April 16, 1746, in a remote field on the windswept moors of Culloden, two armies met to decide the future of Britain. The Jacobites, led by Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie), were determined to restore the Stuart monarchy to the British throne. The Duke of Cumberland’s government army, loyal to King George II, stood ready to defend the status quo. The resulting battle was one of the most decisive and brutal in British history.

In less than an hour, the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 was crushed, with thousands of Jacobites killed or wounded. Culloden was not just a military defeat but a turning point that reshaped the Scottish Highlands and solidified British rule over Scotland. The British government launched a relentless campaign to dismantle Highland culture, outlawing Gaelic, tartan, and the traditional clan system. The battle’s impact extended far beyond the battlefield, leaving a lasting legacy of loss, displacement, and forced assimilation that would forever change Scotland. This article will take a closer look at the events of Culloden, its impact on Scotland, and its role in marking the beginning of a new era in British history.

The Road to Culloden: The Jacobite Uprising of 1745

Jacobitism was a political movement devoted to restoring the Stuart dynasty to the British throne. The movement had a strong foothold in Scotland, as many Highland clans remained loyal to King James II, who had been deposed by Parliament in 1688. His son, James Francis Edward Stuart, and his heirs were seen as the rightful rulers of the British Isles, rather than the German King George II.

As part of an effort to weaken Britain, the French government provided limited military aid to the Jacobites. It encouraged Prince Charles Edward Stuart to attempt to lead a rebellion. Charles had strong personal reasons to want to restore his family to the throne, and he traveled to Scotland in July 1745 to raise an army.

Bonnie Prince Charlie’s efforts in 1745 were a dramatic success. Landing in Scotland, he was able to rally a number of Highland clans to the Jacobite cause. With a small but enthusiastic army, Charles marched south to Edinburgh, which was captured with no resistance.

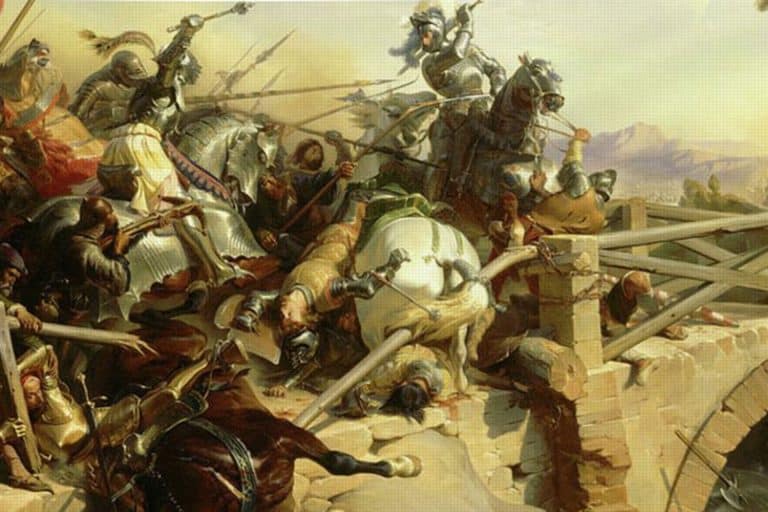

The Jacobite army met a government force at the Battle of Prestonpans in September 1745. Employing a tactic known as the Highland charge, the Jacobites made an all-out attack with broadswords and muskets. The British were unable to stop the charge, and the government army was defeated in under 15 minutes. The victory was a sensation, and Charles was buoyed by the support he found and convinced that he could win the throne. Charles left Edinburgh and marched south into England.

The Jacobite army moved quickly, reaching Derby in November 1745, only 130 miles from London. Yet despite the early success, the Jacobite army was increasingly encountering resistance rather than recruiting English and Welsh allies. The expected rebellion of English Jacobites failed to materialize, and promised French reinforcements had not yet arrived. The British army was reorganizing, and King George II’s Hanoverian forces were ready to fight back. Jacobite supply lines were stretched and threatened with being cut off entirely. The commanders of the Jacobite army, against Charles’s personal wishes, abandoned the advance on London and returned to Scotland.

The decision to retreat from Derby signaled the beginning of the end for the rebellion. The Jacobite army won another battle at Falkirk in January 1746, but it was increasingly short on supplies and discipline. The British, led by the Duke of Cumberland, pressed relentlessly on the retreating Jacobite army, leaving them little time to regroup or recover. The situation in Charles’s army became increasingly divided, as many Highlanders, who had been on the march for months, began to desert the cause. Cumberland’s army pushed on, leaving Charles to make his last stand at Culloden Moor in April 1746. The final battle was bloody and brutal, and it would be the end of the rebellion.

The Battle of Culloden: April 16, 1746

The Battle of Culloden was the final and most significant engagement of the Jacobite Rising of 1745. The battle took place between the Jacobite army of about 5,500 Highland clansmen, led by Prince Charles Edward Stuart, and the British army, led by Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, the son of King George II. The Jacobites, having been cornered, outnumbered and outmanoeuvred, were caught on the open field of Culloden. Cumberland, on the other hand, had 7,000 to 9,000 soldiers under his command. His troops were better trained and more battle-hardened. Despite the bravery and determination of the Highlanders, the British forces had a significant edge that, on the morning of April 16, would prove insurmountable.

The marshy ground of Culloden Moor proved to be a terrible battleground for the Jacobites. It took away the element of Highland charge, their speed, and manoeuvrability – the strengths they had used to win battles in the past. The hilly terrain slowed their movement and forced them to disperse, reducing the effectiveness of their attacks. Previous battlefields had enabled Highland warriors to rush and close with the enemy, but the Battle of Culloden left them open to heavy casualties from long-range fire. As the battle commenced, the Jacobites were unable to form a tight formation and faced a barrage of artillery from the British lines.

The Highland charge was the one strategy of the Jacobites most feared and their only hope. But Cumberland’s army was ready. As the Highlanders rushed in, they were met by a withering storm of musket fire, which cut down men as they approached British lines. The compact formations of the government army rushed in to exploit the gaps in the Jacobite ranks. The scene was a grim one: according to the historian John Prebble, “They fell in clumps, blown apart by cannon fire, slashed down by sabers before they could raise their broadswords”. The charge, which had been so successful at Prestonpans and Falkirk, had been completely stopped at Culloden.

Superior artillery tactics, aided by grapeshot, also decimated Cumberland’s Jacobite opponents. The lightly armored Highlanders had no protection against the blasts. The trained British soldiers quickly reloaded their muskets and kept up a steady, continuous fire. The bayonet, rather than the sword, then met those members of the charge who managed to reach the British lines. British infantry had been drilled to thrust their weapons rather than slash, and were thus far more deadly in hand-to-hand combat. The Highlanders, already tired and confused, could not break through.

The battle had lasted less than an hour. By the time the fighting stopped, more than 1,500 Jacobites were dead, and many hundreds more were wounded. British losses had been less than 300 men. Jacobites who had tried to flee were mown down as Cumberland’s men relentlessly chased them across the moor. The British cavalry then hunted the retreating Highlanders and butchered many of them. Jacobite survivors who were taken prisoner were often hanged or imprisoned. Others were sent to the colonies to work as forced laborers.

The Battle of Culloden was the end of the Jacobite cause. Bonnie Prince Charlie had inspired thousands of men to rebel against the British crown. Now he had fewer than 100 men left and barely managed to escape the field. He escaped into the Highlands and eventually back to France, where he spent the rest of his life in exile. His dream of a Stuart restoration had turned to ashes. The British government was determined that another rebellion should never be possible. Cumberland’s soldiers hunted down and executed fleeing Jacobites.

The Aftermath: The Suppression of the Highlands

Despite the Jacobites’ crushing loss at Culloden, the war was not over. Beaten, bloodied, and desperate, Prince Charles Edward Stuart was the only significant figure left. He eluded capture for five months, making his way through the Highlands by boat and on foot, sheltered with Jacobite sympathizers and protected by a number of his most loyal supporters. One famous Highlander, Flora MacDonald, assisted his escape to the Isle of Skye by dressing him in women’s clothes as a maid.

In the following months, the Scottish clans rallied, gathering support for another uprising and holding onto the final, faint hope that Prince Charles might return. But the British government took no chances. The surviving Jacobites and the Highlanders who had fought with them could not be allowed to rebuild their forces and take up arms again.

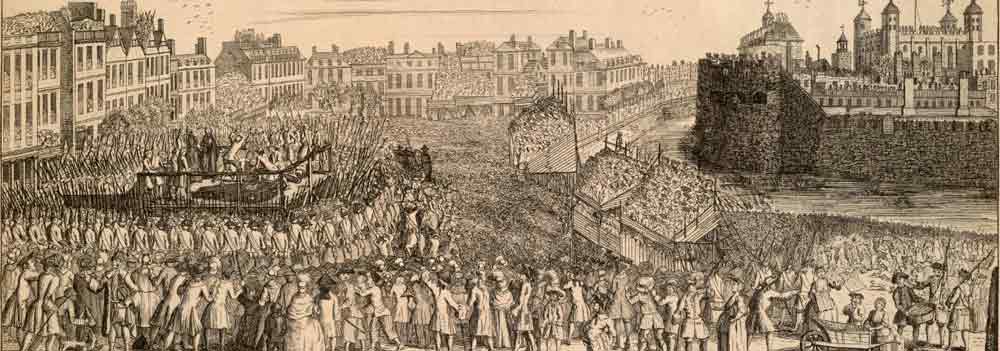

Instead, the Duke of Cumberland, King George II’s son, began a program of reprisals that quashed the final hopes of a Stuart restoration. His forces pursued the retreating rebels through the Highlands, hunting down and executing prisoners. The homes of known rebels were burned to the ground, and anyone who had taken up arms with the Jacobites was given no mercy. Many were killed on the spot, while others were hanged in public, as a warning to any future rebels. Cumberland’s tactics were so vicious that he is still remembered in Scotland today as “Butcher Cumberland”.

The captured Jacobites were dealt with quickly. Hundreds were imprisoned in abominable conditions, while others were executed or transported to British colonies in North America and the Caribbean, where they were sold into indentured servitude or forced to work for long sentences. In Edinburgh and London, high-ranking prisoners were hanged, drawn, and quartered in public spectacles.

In addition, the British government took steps to try to eradicate Highland society itself. Jacobite support came in large part from the clan system, and as a result, it was systematically targeted. The Highland Clearances saw lands taken from Jacobite supporters and their communities driven out. Over the coming decades, many of these landlords forced their tenants off the land to make way for large-scale sheep farming, causing thousands of Highlanders to move to urban areas or emigrate abroad. In this way, the Highlands’ demographic and cultural identity began to change significantly.

In an effort to further break the Highland clans, the British government also passed the Act of Proscription in 1746, which outlawed many traditional Scottish customs. From this point, it was illegal to wear tartan or kilts, carry weapons, or, as the bagpipes were considered an instrument of war, even play the bagpipes. This was done to both punish the clans and prevent them from being in a position to support the Jacobites again. Punishments for breaking these laws were typically harsh, with imprisonment or deportation being the most common sentences.

The most significant long-term impact of the Battle of Culloden was undoubtedly the cultural genocide of Highland culture. The decimation of the clan leadership and the prohibition of cultural symbols left many Scots with no choice but to assimilate into British culture or leave Scotland entirely. The loss of language, tradition, and, most devastatingly, land, changed the course of Scotland’s history forever and has remained a painful scar on Scottish history and national identity. While the Highland way of life would never be the same, the romanticism of the Jacobites and their fight for independence would continue to shape generations to come.

The aftereffects of Culloden were not just the end of a rebellion, but rather the forced incorporation of Scotland into a centralized British state. The battle’s long-term legacy is still seen today, with many Scots citing Culloden as the end of Scottish sovereignty and as a symbol of resistance against oppression. While the Jacobites failed to take the crown, their impact on Scotland’s history and cultural memory remains a powerful reminder of when the Highlands rose in open revolt against the British government.

Long-Term Consequences: A United British Identity

The Battle of Culloden had a profound impact on the Jacobite cause and Scotland as a whole. In the immediate aftermath of the battle, the British government took measures to prevent any future uprisings. The suppression of Highland culture, the decline of the Gaelic language, and Scotland’s integration into the British state changed the country forever. While Culloden was a military defeat, its cultural and political ramifications were far-reaching.

One of the most significant outcomes of Culloden was the decline of Gaelic culture, a cornerstone of Highland identity for centuries. Although the language was never officially banned, it was increasingly marginalized and pushed to the peripheries of Highland society. English became the language of government, business, and education, while Gaelic was relegated to rural areas and isolated communities. As Highlanders were displaced and forced to assimilate, the language began to decline, with fewer communities passing it on to future generations.

The final nail in the coffin for the Jacobite cause was the complete dissolution of the traditional clan system. Clans had been the backbone of Highland society for centuries, but the aftermath of Culloden effectively dismantled them. Land confiscations, economic hardship, and forced displacement left many clans destitute and leaderless. Many chiefs, who had traditionally been the protectors and patrons of their people, abandoned their responsibilities and adopted the ways of the British aristocracy. As landowners rather than warriors, the clans could no longer serve as a military threat to the British state.

The British government further consolidated its hold over Scotland in the aftermath of Culloden. The new military roads and fortifications built in the Highlands allowed the Crown to maintain a degree of control over the region, enabling troops to respond quickly to any future disturbances. The dismantling of the Jacobite power base also saw Scotland become an even more tightly controlled part of the British state, with its political and economic institutions being increasingly integrated with those of England.

Of course, Scottish identity did not die with Culloden, nor did the Highland culture that had been so integral to it. In the 19th century, there was a resurgence of interest in the Highlands and its history, albeit one based mainly on romanticized notions of what it had once been. Writers like Sir Walter Scott popularized the image of Scotland as a land of noble warriors, misty glens, and heroic struggles against overwhelming odds. Queen Victoria’s love of Scotland also helped to fuel a revival of Highland culture, with tartan and kilts becoming popular throughout the country, even among those with no direct ties to the Highlands.

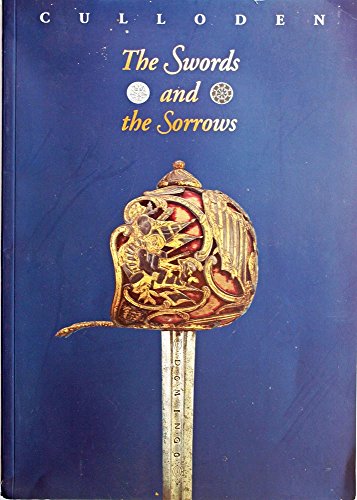

Culloden’s legacy also had a long-lasting impact on Scottish nationalism. While the battle effectively ended the Jacobite cause, it became a symbol of resistance and independence, inspiring future Scottish independence movements. The battlefield itself remains a potent symbol of Scotland’s transformation in the 18th century, with visitors to the site often reflecting on the sacrifices made and the nation’s changed fortunes.

In conclusion, the Battle of Culloden had a transformative effect on Scotland and the Jacobite cause. While it may have sealed Scotland’s fate as part of the British state, it did not extinguish the country’s unique identity and culture. Elements of Highland culture and the Gaelic language have survived, even if they have changed over the centuries. Today, the legacy of Culloden continues to shape discussions about Scotland’s place within the United Kingdom, and its impact is still felt nearly 300 years after the battle.

The Enduring Legacy of Culloden

The significance of the Battle of Culloden extends far beyond its immediate military outcomes. It reshaped Scotland’s future, solidifying British authority over the Highlands and effectively ending the Jacobite threat. The brutal aftermath of the battle marked the beginning of a harsh era of suppression, which left an indelible mark on Scotland’s cultural landscape. The destruction of the clan system and the erosion of Gaelic traditions served to strengthen the British state’s control, leaving a legacy of trauma in Scotland’s national psyche.

The battle’s impact on Scotland was profound and far-reaching. Culloden was the final nail in the coffin for the Jacobite cause, effectively ending any serious attempts to restore the Stuart monarchy and secede from the British state. The defeat also triggered a wave of brutal repression against the Highlanders, which further solidified British control over Scotland. The impact of Culloden on Scotland’s national identity is complex and multifaceted. The battle’s legacy of defeat and trauma has become an integral part of Scotland’s cultural heritage, with the memory of the struggle and its leaders continuing to influence Scottish society to this day.

In many ways, Culloden symbolizes the end of an era for Scotland and the Highlanders. It closed the chapter on the Jacobite movement and its aspirations for an independent Scotland under a Stuart king. The battle’s cultural impact on Scotland cannot be overstated. The memory of Culloden has become an integral part of Scotland’s national identity, shaping its cultural and political landscape for generations to come.

In conclusion, the significance of the Battle of Culloden cannot be overstated. It had a profound impact on Scotland’s national identity, culture, and future, and its legacy continues to be felt to this day. The battle’s cultural effect on Scotland, from the romanticization of Bonnie Prince Charlie to the enduring trauma of defeat, has become an inseparable part of the nation’s heritage. As we continue to grapple with questions of nationalism, sovereignty, and Scotland’s place within the United Kingdom, the Battle of Culloden serves as a powerful reminder of the country’s complex and tumultuous past.