The Black Hawk War and the Struggle for the Mississippi Valley

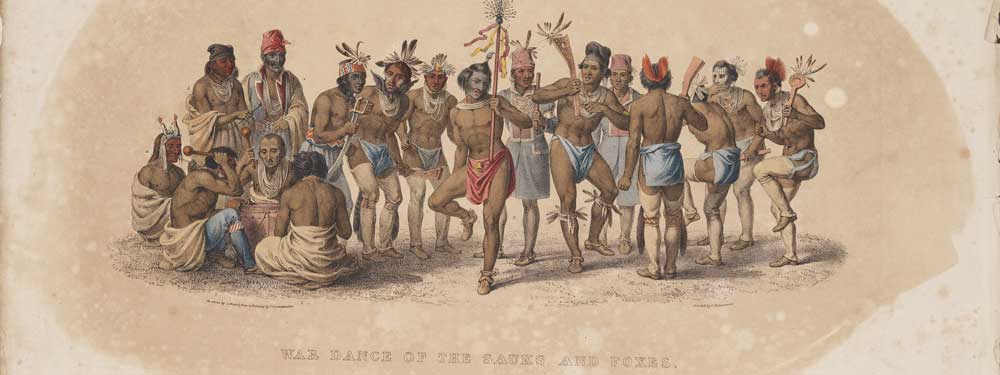

In the Mississippi Valley in 1832, native nations and white settlers collided in a deadly struggle for land, power, and survival. For generations, Sauk and Fox people had hunted and farmed along the river valleys. Still, the rapidly expanding United States was encroaching on Illinois and Wisconsin, with settlers continuing to pour into the region. The simmering tensions between cultures that had persisted on the American frontier for years quickly reached a boiling point, leading to conflict.

Black Hawk, a Sauk leader and the grandson of the well-known Chief Saukenuk, had decided to take action to restore his nation to its homeland. Dismissing a treaty that he and his village had signed as illegitimate and believing their home village of Saukenuk was still theirs to claim, Black Hawk and his followers crossed the Mississippi in an attempt to take back their land. “I touched the goose quill to the treaty, not knowing, however, that by that act I had given away my village,” he would later say. This decision led to the Black Hawk War. This short but costly conflict marked the culmination of efforts to control the Mississippi Valley and the high cost of American westward expansion.

The Mississippi Valley in Transition

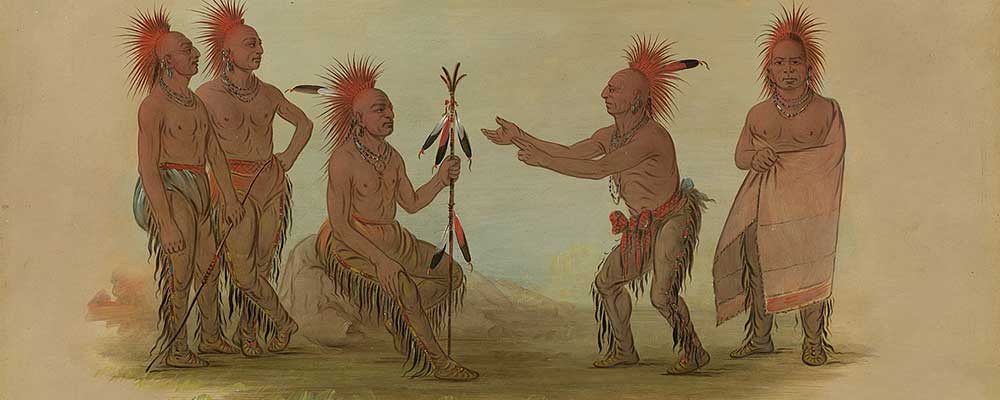

The Mississippi Valley was home to the Sauk and Fox Nations for many generations before settlers began arriving in large numbers. For them, this region with its network of rivers and prairies was the center of their world. The Fox and Sauk built villages, hunting grounds, and sacred sites along this territory. Saukenuk, the Sauk’s main village, was their “Center of the World.” It was located near the Rock River in present-day Illinois. Their way of life included moving around the region with the seasons, hunting game, and planting new crops. Settlers did not have the same connection to the land they began to move into, so many did not understand why losing it was such a deep concern for the Sauk and Fox.

One of the major causes of the war was a controversy over a treaty. In 1804, a small group of Sauk and Fox leaders signed a treaty in St. Louis. The United States claimed that it ceded to them millions of acres in Illinois and Wisconsin. Many Native leaders later denied that they had actually ceded these lands and signed the treaty under duress or through trickery. Black Hawk later stated that “I touched the goose quill to the treaty, not knowing, however, that by that act I had given away my village.” For decades, Native leaders would continue to claim they had not ceded their lands in the Midwest, while the government maintained that it was a legal treaty.

By the 1820s and early 1830s, increasing numbers of settlers began moving into the Mississippi Valley. The region’s potential for rich farmland attracted people who sought to capitalize on the opportunities it offered. Illinois was admitted to the Union in 1818, and migrants flocked to its farms and towns near the villages of Sauk and Fox. Wisconsin was still a territory at the time, but settlers also began to move into that region. In their eyes, the Mississippi Valley was a chance to build prosperous new lives, while the Native peoples living there viewed it as an encroachment on their own territories.

The settlers’ movement into this area increased tensions between the groups. The farmers and town residents who saw Sauk and Fox people returning to Saukenuk in the spring and summer after the planting season viewed them as squatters, rather than as people who rightfully belonged on their land. Native hunting groups and settlers frequently clashed over crops and livestock, increasing hostility between the two groups. Frontier newspapers also spread fear and often exaggerated the actions of Black Hawk and his followers, portraying them as dangerous and aggressive foes, even when they were simply trying to find food and continue their traditional way of life.

The two groups could not coexist peacefully for much longer. Some Sauk leaders, most notably Keokuk, were willing to work with U.S. government officials and settlers, but Black Hawk would not give up Saukenuk. His resistance to leaving land that was part of his people’s heritage was part of a larger conflict between the settlers and Native peoples. For Native Americans, the Mississippi Valley was their homeland, the heart of their identity and traditions. But to the settlers, it was simply a place that was available for people willing to stake their claims and build new lives there. This clash of cultures and values over land and belonging had reached a head by 1832, and war was the inevitable result.

Black Hawk and His Trib

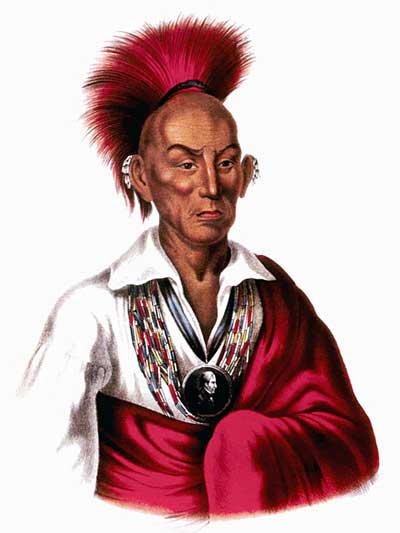

Black Hawk was born in 1767 in Saukenuk, the largest and central settlement of the Sauk Nation. The village was located at the junction of the Rock River with its west fork, in present-day Illinois. He rose to become a renowned Sauk leader through displays of bravery in battle against both rival Indian tribes and later against American troops. He also established himself as a leader through his dedication and sense of responsibility to his people. By the early nineteenth century, Black Hawk was one of the most powerful Sauk leaders, known for protecting his homeland against American expansion.

The Sauk and Fox Nations both held Saukenuk to be of particular cultural and spiritual importance. Saukenuk had been home to many generations, who farmed the land and worshiped there. The village’s proximity to the Rock River valley allowed it to provide for the people during the growing season, with corn and bean fields being planted every spring before seasonal hunting trips were taken. Leaving Saukenuk would mean leaving a sacred land. Black Hawk thus saw forced relocation across the Mississippi into Iowa as both unjust and an attack on his people’s identity.

Indian Creek Massacre occurred on May 21, 1832, near Indian Creek in LaSalle County, Illinois. A band of Potawatomi Indians, with a few Sauk, attacked a group of settlers living in a village on the stream. The Indians had wanted the whites to take down a dam they had built which was preventing fish from entering a stream that flowed past a Potawatomi village nearby.

When the settlers refused, the Indians, numbering between forty and eighty warriors, killed fifteen of the whites, including women and children. Two other young women were taken captive, but they were ransomed and released unharmed. The massacre took place during the Black Hawk War, but the chief Black Hawk had nothing to do with the attack. The incident caused panic on the frontier, with many settlers fleeing to militia forts for protection. There are memorials at Shabbona County Park in Illinois marking the site of the massacre.

In contrast to leaders like Keokuk, Black Hawk was unwilling to cede Sauk territory or leave it behind to maintain peace. He resented that the Sauk had supposedly sold their land in a 1804 treaty, and he firmly believed that treaty to have been fraudulent. The signing had been done by lower-ranking representatives, without the approval or authority of the tribe’s full council. Black Hawk was especially angered by having to witness white settlers moving in and plowing over fields that his people had farmed for generations. He thus saw it as a moral imperative to return to the Rock River and a spiritual requirement.

In 1832, Black Hawk led a band of warriors, women, and children across the Mississippi River into Illinois and back to Saukenuk. The band came to be known as the “British Band” because Black Hawk had formed an alliance with the British against the Americans during the War of 1812. Black Hawk had initially hoped to gain at least some protection from the British or Canadian authorities, but they had been unsuccessful. Black Hawk stated his intention to be that of a peaceful resettlement of their ancestral village. Many settlers and U.S. officials saw this return across the river as an act of armed aggression.

The crossing was a defiant act. The band would not simply give up on their ancestral land; instead, they were attempting to reclaim a part of it while also fighting for the dignity and autonomy of their people. To Black Hawk and his followers, Saukenuk was the soul of their tribe, and it was unthinkable to leave it behind. His decision to lead his followers back across the Mississippi into Illinois led to the series of battles that became known as the Black Hawk War. It was a struggle born from both desperation and courage.

The Outbreak of War

When Black Hawk and his followers crossed back into Illinois, many in his band believed they would be able to plant crops and live peacefully on the ancestral lands of their people. To settlers, however, the return of several hundred Native people—many of whom were armed—appeared to be an invasion. Fear and rumor spread quickly across the frontier, transforming a movement of resettlement into what many whites assumed was the opening of war.

The U.S. government responded by mobilizing state militias to confront Black Hawk’s band. Poorly trained and inexperienced, these militias were often more prone to panic than discipline. This became evident at the Battle of Stillman’s Run in May 1832. A detachment of Illinois militiamen clashed with a small group of Black Hawk’s warriors, but confusion and fear turned the encounter into a rout. Dozens of militiamen fled in disarray, and the engagement emboldened Black Hawk’s followers while spreading alarm across the frontier.

Stillman’s Run marked a turning point, convincing many Americans that Black Hawk’s presence posed a genuine threat. What may have begun as a contested resettlement now escalated into open conflict. Settlers fled their homes, seeking refuge in hastily built forts, while militia leaders called for reinforcements. Newspapers fanned the flames, portraying Black Hawk as a dangerous aggressor determined to drive settlers from the Mississippi Valley.

In the weeks that followed, skirmishes multiplied across northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin. The U.S. Army and local militias pursued Black Hawk’s band, determined to force them back across the Mississippi. Meanwhile, Black Hawk’s group—burdened with families and elders—struggled to move quickly or avoid confrontation. Each encounter pushed the conflict further from negotiation and closer to all-out war, ensuring that bloodshed would define the summer of 1832.

Campaigns and Clashes

The fighting intensified in June, as the retreating Black Hawk’s band reached Apple River Fort, a crude stockade in northern Illinois. Black Hawk’s warriors gave the building an all-day test, only to be repelled by a combination of settler militiamen and civilian inhabitants. As the women rolled bullets and kept the spirits of the fighters up, the Sauk and Fox warriors tried to wear down their opponents. One settler recalled that the “women fought with as much courage as the men.” Ultimately, the attack was a failure, but it served to demonstrate the dire straits of Black Hawk’s band. Cut off from many of their supplies, his people were now foraging for food and equipment in hostile territory as they were pursued.

As the summer months dragged on, the stress of the retreat took its toll on the Sauk and Fox, who were trying to move as many women, children, and older people as possible. The battle at Wisconsin Heights in July was emblematic of the experience. Black Hawk’s warriors held off the U.S. troops and a force of Ho-Chunk and Dakota fighters so that women, children, and elders could be ferried across the Wisconsin River. This time, the delay was costly: many Native men were killed, but the main body of the band was able to slip away. Nevertheless, each day of the retreat saw the band weakened by hunger, exhaustion, and the constant harassment from U.S. regulars, state militias, and allied Native people.

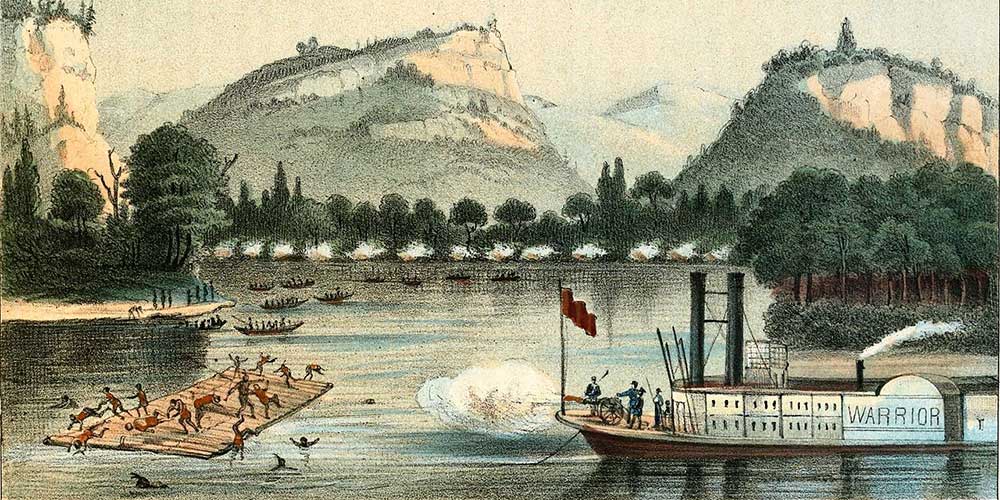

The last stand of Black Hawk’s band would be the Bad Axe Massacre in August 1832. Trying to cross back over the Mississippi River, Black Hawk’s band was cut off by U.S. regulars, steamboats, and militia. What happened next was less a battle than a massacre, with hundreds of Native men, women, and children killed. Survivors would later claim that the river was “running red with blood.” The massacre marked the end of the war, but its memory would be seared into Native minds for generations.

The U.S. military used a combination of state militias and Native allies for most of the campaign. The Ho-Chunk and Dakota were critical in many of the conflicts, motivated by the desire to protect their own standing in a rapidly changing world. For Black Hawk and his people, however, the campaign was less about military movement and more about the difficulties experienced by those fleeing fighting. Fleeing from one side of the state to another, Black Hawk’s people were trying to escape to the forest and swamp with little food and rapidly diminishing strength. The war was becoming an ordeal for everyone involved.

Aftermath and Consequences

The Black Hawk War ended in tragedy and had far-reaching consequences. In its aftermath, the survivors of the conflict dispersed. Black Hawk, on the run after the Bad Axe slaughter, evaded capture by hiding and eventually managed to cross back over the Mississippi River, heading north. He was later captured by the Ho-Chunk, who passed him over to the U.S. officials. His capture effectively signaled the symbolic end of hostilities, but for the Sauk and Fox, life after the war was anything but quiet.

The consequences of the war and subsequent defeat were staggering. The conflict led to the deaths of several hundred Sauk and Fox, the destruction of their villages, and the end of their claims to land in the region. After his arrest, Black Hawk was taken east as a prisoner of war. U.S. officials made him a spectacle as they paraded him through the cities of Washington, Baltimore, and New York, where crowds of gawkers and onlookers came to catch a glimpse of the chief. Newspapers painted him as a heinous savage and a pathetic and broken figure. The tour was, to many Americans, a way to celebrate the might of the United States and its manifest expansion, but it must have been a bitter spectacle to Black Hawk.

Black Hawk was imprisoned at the Jefferson Barracks in Missouri and then transferred to Fort Monroe in Virginia. He was tried as a prisoner of war, although the charges were more symbolic than judicial because his guilt was never in question. Still, his behavior as a captive and his later dictated autobiography created an enduring, widespread interest in the man. Black Hawk’s Life of Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, dictated to a writer and published in 1833, provided him with a voice in American popular culture, even as it underscored and contradicted the prevailing story of conquest.

The cost of the war for the Sauk and Fox Nations was high. Hundreds were killed, and those who survived were forced to leave their ancestral lands on both sides of the Mississippi and to live on reservations in places they had never known. Families were torn apart, traditions uprooted, and cultural touchstones such as Saukenuk were lost. The Black Hawk War, then, resulted in widespread death and dispossession for Native peoples in the area and was one among a growing number of similar cases of removal by the U.S. government that would increase through the 1830s.

The U.S. victory brought increased control over the Mississippi Valley. It eliminated Native resistance to American settlement in the area, thereby clearing the way for more U.S. settlers to claim the land for farms, towns, and trading posts. At the same time, for Native people, it was a reminder that resistance, or even the hint of resistance, would be met with considerable force. The Black Hawk War thus ended Sauk independence in Illinois and ushered in a new era of more explicit U.S. dominance in the area.

Legacy of the Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was brief, but it would leave a long legacy. To the Sauk and Fox, it had been a tragic war. They had lost friends and family, their homes, their freedom, and their place in America. But they had not given up without a fight. The major battles of Stillman’s Run, Apple River Fort, Wisconsin Heights, and the Bad Axe Massacre demonstrated both the bravery of Black Hawk and his followers and the destructive force brought against them. These battles were not soon forgotten by the Native people, who remembered them as a time when their country was invaded and their people were killed.

The Black Hawk War also provided an early stage for several men who would go on to shape the United States in the coming decades. Abraham Lincoln, a 23-year-old militia captain, gained no glory on the field but would later reflect on the value of service. Jefferson Davis, serving as a lieutenant at the time, and General Winfield Scott were also involved, and all three would serve in the Mexican-American War and the Civil War as well. In a sense, the Black Hawk War served as a proving ground for future American leaders.

To American policymakers, the Black Hawk War had proven to them that the Native peoples of the land would have to be removed or contained. The violence of 1832 would harden Washington’s and the frontier’s thinking on the matter, speeding up the removal policy that would culminate in the Trail of Tears a few years later in the decade. The Mississippi Valley, a region once home to thriving and diverse Native American communities, became increasingly a place of settler society and a cautionary tale.

Black Hawk, for his part, refused to be written out of history. His autobiography, dictated in 1833, was published that year and became one of the few Native accounts of the era. He gave voice to his people’s suffering and explained their motivations, sharing his story in a way that was rarely preserved in American history. “I fought hard, but your guns were well aimed,” Black Hawk recalled. He acknowledged both the futility of the Native resistance and the need to have tried. Black Hawk’s words would serve as a lasting reminder of both his own dignity and that of those he commanded in battle.

The memory of the Black Hawk War today is two-fold: a tragedy of loss and a narrative of resilience. For Native nations, it represents the resistance of a people fighting to protect their country against an invading force. In the history of the United States, the Black Hawk War serves as a poignant reminder that the country’s territorial expansion came at a steep human cost. The legacy of the war remains not only in its military records and treaties, but also in the words of those who stood to protect their country, allowing those who fought to remember their struggle.

Conclusion

The Black Hawk War was far more than a fleeting frontier skirmish. It was a defining struggle over the future of the Mississippi Valley, pitting the survival of Native nations against the relentless push of American expansion. The battles and massacres of 1832 laid bare the enormous cost of that expansion—dispossession, bloodshed, and the uprooting of communities whose ties to the land stretched back for centuries.

Yet within this tragedy lies a story of resilience. Black Hawk’s refusal to surrender Saukenuk without resistance ensured that his people’s struggle would not vanish into silence. His defiance, though ultimately crushed, remains a symbol of the human fight to defend homeland and identity against overwhelming odds. Remembering this conflict reminds us that the history of the Mississippi Valley is not only about conquest but also about the enduring courage of those who resisted.