The Final Run of Engine 382: Inside Casey Jones’ Fateful Journey

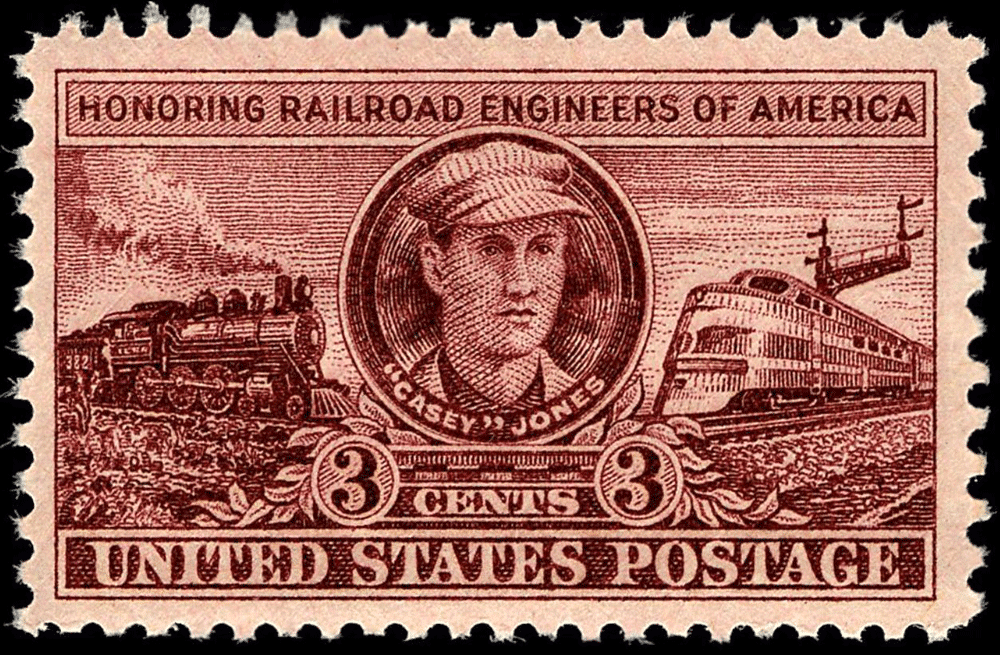

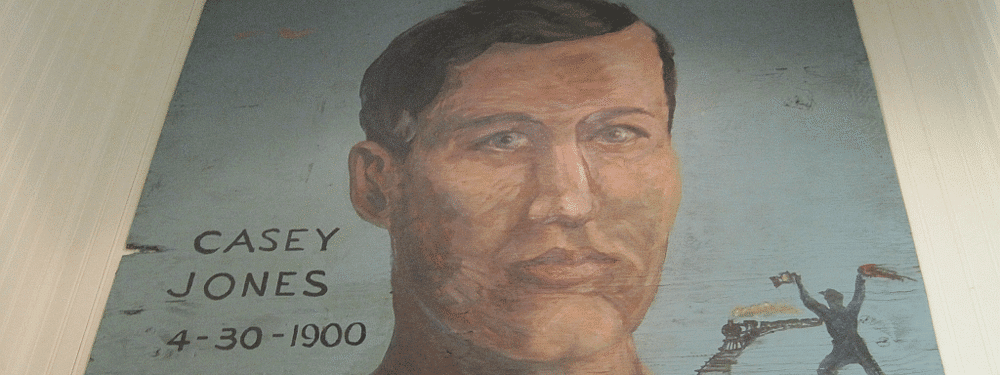

John Luther “Casey” Jones was no ordinary railroad engineer. Revered by his peers for his unwavering dedication, remarkable timing, and calm command under pressure, Casey earned a reputation as one of the fastest and most dependable men on the rails. Operating for the Illinois Central Railroad at the turn of the 20th century, he was known for his punctual arrivals and the personal care he gave to his locomotive, Engine 382. However, his name would become etched in American folklore not just for how he lived—but for how he died.

On the night of April 30, 1900, Casey Jones climbed into the cab of Engine 382 for a run that was not originally his. A fellow engineer had fallen ill, and loyal to the line, Casey stepped up to cover the shift. As the Cannonball Express steamed out of Memphis, Casey and his fireman, Simeon “Sim” Webb, knew they were running behind schedule. Determined to make up lost time, Casey pushed the engine hard through the Mississippi night—unaware that this run would become his last and that his heroic actions in the face of disaster would make him a legend.

Setting the Scene: America and the Railroads in 1900

Railroads had become the lifeblood of America at the turn of the 20th century. The expanding iron network of tracks linked rural hamlets and industrial cities from coast to coast. Trains carried mail, freight, and passengers faster than ever before, forever changing the economy and the way people interacted. The locomotive was an awe-inspiring symbol of industrial might, and the men who worked on them, primarily engineers, were considered daring heroes at the vanguard of the march of progress. The job had its perils, however. Trains often ran rigid schedules on difficult terrain, in inclement weather, and had to share the track with other trains going in opposite directions.

Casey Jones worked for the Illinois Central Railroad, one of the largest and busiest lines in the nation. He had developed a reputation as a safety-conscious, high-speed operator. Casey always ran “on the dot” and took pride in keeping his engines in top mechanical condition. Other engineers on his line respected him as an experienced and steady hand on the throttle. Casey took pride in running his train exactly as scheduled and was known to treat every run as his own personal mission. Engine 382 was a mighty steam locomotive with a top speed of around 60 mph. It was a robust, bullet-nosed design intended for speed and endurance—precisely what Casey Jones needed.

Engine 382 was scheduled to pull the Cannonball Express, a passenger service that ran between Memphis, Tennessee, and Canton, Mississippi. The run had its share of challenges, including long stretches of single track, irregularly timed schedules, and numerous sidings and junctions that could result in close calls. But Casey Jones and other high-speed operators working the Cannonball helped earn the line a reputation for quick service. Casey, who was off-duty on the night of April 29, 1900, jumped at the chance to take over a run that was already behind schedule. He didn’t expect any problems—it would be just another night on the rails.

The Call to Duty: Why Casey Took the Run in 1900

April 29, 1900, was not a day Casey Jones had planned to be at the throttle of Engine 382. The late-night Cannonball Express run from Memphis to Canton had been assigned to another engineer, but when that man became ill, Casey volunteered to take the job. Casey never hesitated to lend a hand to a fellow crewman in need, and despite having not slept for many hours following the earlier run, Casey readily agreed to take the train south.

Casey Jones had a work ethic that was the stuff of legend, and he would often go above and beyond to do what was expected. He was a rock, the epitome of dependability, and had a well-earned reputation that preceded him throughout the industry, among both his peers and superiors.

Simeon “Sim” Webb was Casey’s regular fireman and was riding with him on this run. Webb was a trusted, well-liked colleague who had worked with Casey for many years. They were close friends, as most firemen and engineers are who have spent hundreds, if not thousands, of hours riding together in the cab of a locomotive. Webb would have Casey’s back, as he knew his habits, instincts, and all his idiosyncrasies; they were, in short, absolutely in sync.

Webb knew just what Casey expected of him at all times, making their relationship essential for the successful navigation of the demanding and often hazardous world of railroad operations. It was that knowledge that allowed Webb and Casey to run so many trips so safely.

Jones and Webb were already running behind schedule. With a tight timetable to maintain and passengers who had high expectations of being on time, there was significant pressure to make up time along the route, but Casey Jones was confident that he could regain those lost minutes; of course, he could.

The Journey Begins: High Speed and Heroic Timing

Engine 382 pulled out of Memphis just before midnight on the night of April 30, 1900. Under the soft light of the moon, the Cannonball Express pulled out of the station, only about 45 minutes late. As Casey had a reputation around the Illinois Central Railroad for having no fear of punctuality, few in the crew were worried about losing too much time with Casey behind the throttle. Casey was running one of the fastest trains on the IC, and he intended to make the train look fast that night.

Throwing down more coal and throttling forward, Casey took the train into the peaceful Southern night. The Cannonball blasted through the darkness, whipping through the air as though it were a bullet from a gun. Telegraphers and stationmasters at the small towns along the way all noted Engine 382 thundering past, well before they were due. Casey, through a combination of skill and knowledge of the road, managed to make up nearly all of the time that they were late, something that few engineers could have done in his place.

Sim Webb, who had been on many trains with Casey throughout his career, later wrote that the ride was smooth and fast on the night of April 30. Riding through towns and the open road, the Cannonball flew by with hardly a jolt from Casey’s expert throttle. In several interviews, Webb told interviewers that “it ran like silk” which is a testament to the skills of Casey Jones. In addition to the speed, Webb marveled at how the engine was able to roar so powerfully down the tracks, without a great deal of smoke belching from the stack.

The train was gaining on the schedule as they approached the small town of Vaughan, Mississippi. However, unknown to Casey and Webb at the time, an air hose had broken on a stalled freight train, leaving it sitting on the main line ahead of them. As the train approached, the signalman there tried to flag the pair down. Coming in at a full head of steam, the Cannonball Express was not easy to flag down at such an hour.

The Fatal Moments at Vaughan

Flags were waved, but the Cannonball Express was too fast for a last-minute warning. The poor visibility and speed gave Casey precious seconds to decide what to do after spotting the blockage.

Casey Jones reacted instinctively when he saw the freight cars across the track. Slipping on the air brakes and screaming the train whistle, Casey did not jump from the cab. He tried to slow it down so that the collision with the freight train wouldn’t be so violent, sparing as many lives as he could. Casey had one thing in mind when he did that: saving the lives of his crew, including the young Sim Webb, standing beside him.

Webb did not doubt that the crash was fatal. He jumped out of the cab window into the night before the train hit. In the years after the wreck, Webb often recalled that final look he got of Casey, and that Casey kept his hands on the controls and remained concentrated until the end. “He stayed with the engine,” Webb said. “That’s what he always did. He wasn’t going to let his train crash full speed.” That would lead to Casey’s death but spare others.

Engine 382 crashed into the rear end of the freight, and its whole front caved in. However, Casey’s action of slamming the brakes saved it all. The brakes slowed the train just enough to prevent it from falling apart. Thanks to Casey Jones, the passengers and crew suffered from only minor injuries. Casey Jones was found in the cab with one hand on the brake and the other on the whistle cord. His heroism made him an immortal American folk hero.

Aftermath of the Crash

The wreck at Vaughan had pancaked Engine 382 against the rear of the freight train’s caboose. The collision had sheared off the front of the engine and splintered the caboose’s wood to matchwood. Amazingly, no passengers or crew aboard the Cannonball Express had been killed or seriously hurt in the wreck—except for one. Casey Jones, who had stayed at the throttle to slow the train as much as possible, was the only casualty.

Illinois Central Railroad reports of the wreck announced the tragic loss of Casey Jones and praised his heroism in sacrificing his life to save the train. The reports noted that his actions had probably averted a far worse disaster. Newspapers throughout the country honored Jones as an example of dedication and courage. Sim Webb’s account of the last moments of Casey’s life further stirred the public. Casey was a hero to the public because he gave his life to save others.

The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers offered funereal eulogies to Casey Jones’ memory and honored his dedication to duty under the worst of circumstances. Fellow railroaders paid tribute to his bravery and professionalism. Casey was admired by many in the nation’s working class, especially in the other dangerous trades. For them, Casey Jones represented all that was best about life on the rails: fast, fearless, and loyal to the end.

The Birth of a Legend

Days after the crash, news of Casey Jones’ last run spread like wildfire. A local disaster had become a national headline. Within weeks of his death, a friend and fellow engine wiper named Wallace Saunders is said to have written the first known version of “The Ballad of Casey Jones,” his words an admixture of fact and folklore, which distilled the last run’s drama into folk verse. Set to the same music as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” the ballad made a folk hero of Jones almost overnight.

Vaudeville performers, labor organizations, and folk musicians carried the song and its refrain to others who changed it and added verses of their own. Much of what is remembered about Jones is not quite true. The notion that he was racing another train and that he was smiling when he died was added to the legend after the fact.

The newspapers reported a man who would not abandon his post and risked all to save others. He was the last in a dying breed. For an America increasingly industrialized and mechanized, Casey became a folk hero. Stories of men like him were increasingly in short supply; it was a world of anonymous cogs. Casey Jones, the common man who went down with his ship, became the hero men wanted their children to grow up to be.

The decades have seen hundreds of books, ballads, and retellings of Casey Jones’ final run, including everything from children’s storybooks to blues tunes to animated cartoons. In the pantheon of Americana, Casey Jones is a fixed star. We remember his speed, his skill, and his sacrifice; his eyes on the track, at the throttle, the steed beneath his feet, even as the smokestack behind him belched flame, and the whistle wailed its final, desperate warning.

Historical Analysis: Fact vs. Folklore

Over the years, however, the story has gathered details that further muddy the line between history and fiction. In the ballads and retellings, Casey is almost always speeding recklessly through the night, either “riding the brakes” or racing another train. In fact, it’s more likely he was working within the normal parameters of an engineer of the time, just catching up on time on an express schedule.

The description of him smiling or waving as he neared the stopped train has more poetry to it than probability. These little additions notwithstanding, the basic story is still true: Casey Jones died at his post, trying to save the lives of others. The fact that he was the only fatality of the crash is a testament to his presence of mind and his commitment to his job.

He could have abandoned Engine 382 when it failed to stop, but his decision to remain at his post and attempt to stop the train with his locomotive was one of professionalism and self-sacrifice. His peers commended Casey’s actions, and his example of responsibility under pressure was used in early union publications to educate others.

In separating fact from fiction, the legend of Casey Jones is a powerful tale of responsibility and courage. The legend may have dressed the facts up with colorful details, but it’s the fact of his bravery that makes him still matter more than a century later. The fiction doesn’t tarnish his story—it just makes it more human. And it’s that humanity that is Casey Jones’s lasting legacy, a man who met tragedy with grit, resolve and an unshakeable sense of responsibility.