The First Expedition to The South Pole & What We Have Learned

For centuries, the South Pole and Antarctica have been a complete unknown, a continent covered with ice and snow. Countless stories have been written of the journeys and voyages to the white continent; it took the stubbornness of man to conquer a seemingly unconquerable kingdom. Looking back at past Antarctic expeditions, we have come to understand that our Antarctic history is also our history, and it has contributed significantly to our knowledge of our planet and the frozen desert.

The Alluring South: Early Ventures to Antarctica

Maps, since the time of ancient Greece and Rome, had hinted at the possibility of a great southern land, but had presented no factual evidence. As navigation improved, the search for Terra Australis increased during the 18th and 19th centuries.

In 1768-1779, Captain James Cook pushed further south than any previous mariner. Cook never actually saw the Antarctic continent, but his reports of the iceberg-strewn seas whetted the appetites of many.

Although there were many reasons none reached the Antarctic mainland, the biggest hurdle was that they could not get there! The Southern Ocean has always been a tough ocean to navigate. Waves of monstrous proportions and unpredictable weather patterns made sailing in icy waters a perilous undertaking. In addition, without knowledge of the Antarctic ecosystem, even if the explorers made it there, there was no guarantee they could survive.

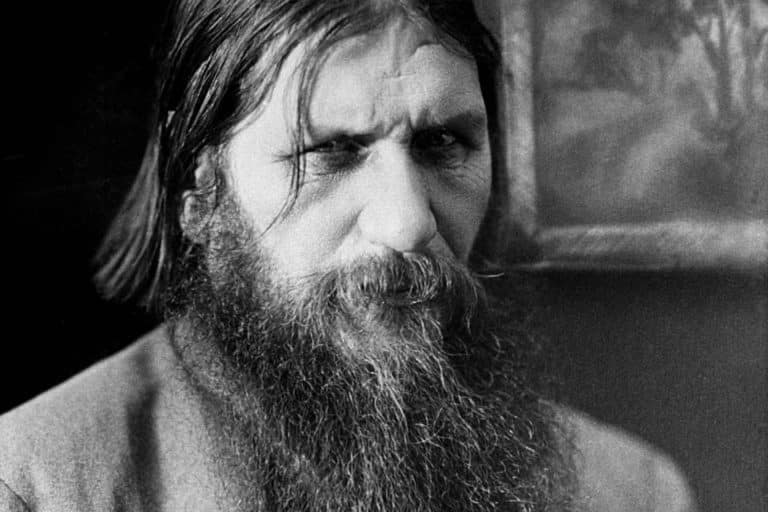

Roald Amundsen of Norway / Wikipedia Commons / Public Domain

Robert Falcon Scott of Britain – Photo by John Thomson – Alexander Turnbull National Library, New Zealand / Wikipedia Commons / Public Domain

A Duel in the Snow: Amundsen versus Scott

The 20th century’s race to the South Pole is one of the most dramatic episodes in the history of exploration. In this competition between Norway and Britain, two of the greatest maritime nations of the age, Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott represented the summit of their countries’ polar experience. Each man was the standard-bearer for a unique national approach to the conquest of the last great wilderness on Earth. Yet their distinct personalities, strategies, and mindsets would lead them down radically different paths to the pole and, finally, to the vastly different outcomes for their expeditions.

In one of his race’s first moves, Amundsen almost entirely hoodwinked his own crew. He secretly prepared to sail the ship Fram to Antarctica rather than the North Pole. His two small ships slipped away from the pack ice and out of the Norwegian ports without anyone, including his ship’s captain, knowing the new destination. It was a last-minute decision that could easily have backfired.

Amundsen, however, based his own plans on extensive polar experience. He refined all the details—optimal routes and their possible variations, equipment and supplies, food rations and techniques of travel, survival protocols in case of the unforeseen, and all other aspects of the expedition. In Amundsen’s preparations, the Antarctic became a test of extreme logistical organization, and there was no room for mistakes.

Amundsen’s planning took years and was based on his understanding of survival from the study of native Arctic peoples and his own experience. He honed every element of the journey to the limit of efficiency: the route and supply depots, the clothing and boots, the food and fuel rations, and the use of sled dogs.

There was nothing untested in his preparation. His team used dog teams trained for hauling sledges, something almost unheard of in polar exploration to that point, and they wore fur clothing, also an anathema to explorers who had not been to the Arctic, because it kept out the cold while still allowing whole movement and range of motion. Amundsen was the acknowledged master of polar travel, and by the time he began, he knew the race for the pole was already a foregone conclusion.

Scott’s Terra Nova expedition had a different focus. Scott was a naval officer and a gentleman scientist committed to discovery. His expedition was designed not just to reach the South Pole, but also to explore the Antarctic and its regions, with research at every stop along the way. A multidisciplinary team of geologists, biologists, meteorologists, and oceanographers made extensive collections, even during the two months of travel required to reach the South Pole and then the months needed to return.

Scott brought dogs, an entire team of specially selected Siberian ponies to pull sledges, and two experimental motor sledges based on the latest technical advances in the field. He even made an additional poniesledge from a custom-designed aluminum framework. In many respects, these choices reflected the practicality and technological optimism of the early 20th century, but the Antarctic did not cooperate.

The motor sledges broke down almost as soon as they were used, with one sinking and the other freezing up, and could not be recovered for repair. The ponies had similar problems: they sank into soft snow, were repeatedly injured, and eventually could not be used at all. They had to be killed and abandoned. In short order, Scott was forced into one of the most labor-intensive and energy-sapping forms of sledging in existence: man-hauling.

Amundsen and his team made steady progress toward the pole, a relatively short 800 miles from the Bay of Whales. The Norwegian team also placed its supply depots with navigation markers and skied to the pole using a route the expedition had preselected. The sled dogs performed remarkably well, pulling the sledges at high speeds across all types of terrain, and the food and clothes kept them warm and energized. Amundsen’s five-man team to the pole were skilled skiers with experience in polar travel.

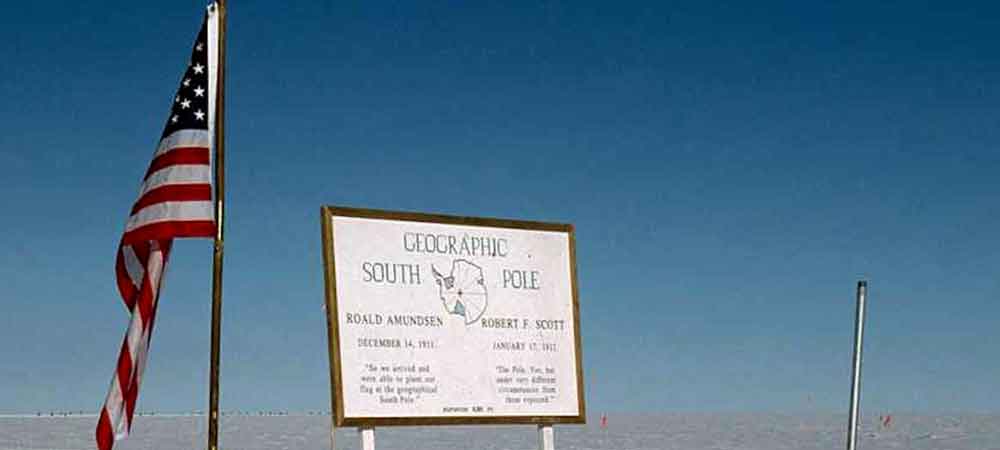

On December 14, 1911, the team planted the Norwegian flag at the geographic South Pole and spent about a week confirming and recording observations before returning towards the coast. They left a tent and documents for Scott and his team, in case he had not yet arrived. Scott and his team arrived at the South Pole on January 17, 1912, to find that they had been beaten by just over a month.

The British expedition group reached the pole to the sound of howling wind. Scott’s diary entry, a beautiful last testament to the optimism of exploration, is also an act of grace to his opponent. It was the Norwegian flag and his carefully left notes that greeted Scott’s team on the 17th.

Scott’s next days and weeks would be spent recording his observations while retreating from the pole, until one by one the men would die of exposure and exhaustion in their tent at the edge of the Beardmore Glacier. Just 11 miles from a depot with food and fuel to make their journey back to base camp possible, a nine-day blizzard had cut the group off. Scott wrote an eloquent last note for his companion, Edward Wilson, and together they laid out the sledges and most of their remaining equipment to make shelter for their last days, all the while documenting their observations.

In March 1912, a search party discovered their bodies, the remaining equipment, and their journals and specimens. The story of Scott’s return journey, like the entire Terra Nova expedition, had a complex legacy. The successful return of their specimens meant that scientists could use many of their observations for decades to come. Yet the way in which Amundsen and Scott ultimately completed their missions would shape polar exploration and its narratives for generations.

These two expeditions offer contrasting styles of exploration: one optimized through adaptation and learning from past successes and failures, and the other through scientific method and technological progress. They also represent the strengths and weaknesses of both approaches. The solutions offered by Amundsen relied on the experience of explorers who had learned from generations of Inuit hunters, and on the use of these strategies with the best technology of the day.

Scott brought cutting-edge technology of the age to the Antarctic. Still, the distances, isolation, and conditions of the polar plateau had a levelling effect, revealing the fundamental weakness of his logistical and scientific approach. The dominance of the southern ocean meant that if humans ventured out to its coasts, they had to be prepared for a grinding battle against some of the harshest conditions on the planet. In the end, nature won.

The Triumph of Amundsen and Its Significance

The outcome of Roald Amundsen’s expedition to the South Pole in December 1911 represented a monumental achievement in human exploration, showcasing the power of meticulous preparation and respect for the unforgiving polar environment. Unlike previous polar expeditions, which were marked by harrowing struggles against nature, Amundsen’s journey to the South Pole was characterized by precision and an understanding of the human relationship with nature. He and his team reached their goal and returned home safely, an outcome not always ensured in the era of polar exploration.

One of the most significant achievements of the Amundsen South Pole expedition was, of course, the triumphant arrival of the entire team at the South Pole and their safe return to their starting point in Hobart, Australia. This outcome was by no means a certainty in the era of polar exploration, given the numerous challenges and dangers posed by the Antarctic environment. Amundsen’s dietary and clothing choices, as well as his reliance on dog sleds, played a crucial role in ensuring the mission’s success by providing the team with efficient, warm, and rapid travel options. This enabled them to conserve energy, minimize risk, and reach their destination without suffering the tragic losses that had befallen some of their contemporaries.

Amundsen’s team’s observations and practical knowledge gained during their journey to the South Pole also significantly contributed to the era’s understanding of the Antarctic environment and the challenges of polar exploration. The expedition members documented weather conditions, ice formations, and navigational experiences, which provided valuable data for future explorations and scientific studies. These insights, combined with Amundsen’s careful planning and adaptation of indigenous Arctic techniques, offered lessons in sustainable logistics and the importance of scientific and cultural understanding in overcoming the challenges of extreme environments.

The success of Roald Amundsen’s South Pole expedition was not only a triumph of human ambition but also a demonstration of the effectiveness of careful preparation, scientific reasoning, and cultural adaptation. The team’s ability to reach the South Pole and return home safely, along with their practical knowledge, had a significant impact on polar exploration and set new standards for future expeditions. By integrating lessons from indigenous Arctic cultures, focusing on sustainability, and approaching the expedition with a deep respect for the power of nature, Amundsen and his team rewrote the rules of polar exploration, influencing generations of explorers and reshaping humanity’s understanding of its relationship with the most remote and challenging environments on the planet.

From First Steps to Modern Scientific Hub: The Evolution of Antarctic Exploration

After the feats of Amundsen and Scott and their expeditions to the South Pole, the South Pole became a stage for international scientific collaboration rather than national competition. During the early stages of the Cold War, there were fears that the continent might become another region of the world subject to division and control by military powers, but this did not happen.

A turning point for science in Antarctica was the International Geophysical Year of 1957–58 when twelve countries set up over 40 research stations. Studies during this year included investigations of the geology, meteorology, ionospheric physics, geomagnetism, auroras, and cosmic rays, among others. At the end of IGY, representatives of these nations signed the Antarctic Treaty in 1961, which banned military activity and reserved the continent for peaceful scientific research.

In the following decades, the continent was peppered with research bases from numerous countries. The findings of scientists stationed at those bases are starting to reveal the climate history hidden in Antarctic ice, including the discovery of lakes beneath the ice, the uncovering of the unique ecosystems of the Southern Ocean, and even the use of telescopes on the ice to look back in time at the formation of the universe.

Decades of research in Antarctica have taught us just how critical the continent is in the global climate system and in the years since Amundsen and Scott, evidence of climate change has been mounting, including dramatic changes to the Antarctic Peninsula’s climate, where recent summers have been completely ice-free. The change in Antarctic ice sheets has been most rapid in the West Antarctic ice sheet, where ice loss is affecting sea levels worldwide.

In addition, the continent’s relatively pristine environment has provided scientists with a means of controlling for human impacts in more environmentally degraded regions. Just as scientists have been revealing the continent’s deep climate history, they have also been finding that large areas of the continent, previously thought to be lifeless, actually host massive ecosystems under the ice.

In the years since the end of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration, the continent has become a site of international scientific collaboration and a reminder of how much work remains to understand better the effects of climate change in this increasingly fragile environment. The journey from Amundsen and Scott’s polar explorations and eventually arrival at the South Pole to the many different research fields at work on the continent in the 21st century reflects human curiosity and growing understanding of our place on the planet. Stories of courage and sacrifice in the exploration of the white continent, a thirst for knowledge, and an ethos of international collaboration and cooperation still resonate powerfully.