The Fragile Frontier: Mormon Settlers and the Mountain Meadows Massacre

The Mountain Meadows Massacre, one of the most contentious events in American Western history, took place in September 1857. A group of Mormon settlers and Native Americans ambushed and killed emigrants from Arkansas to California who were passing through on their journey westward. The massacre, however, did not occur in a vacuum. It was the culmination of rising tensions between Mormon settlers and the United States government, which had been escalating over several years of territorial disputes and religious persecution.

To fully understand the events leading up to the Mountain Meadows Massacre, one must first look at the precarious existence of Mormon communities in the Utah Territory and their attempts to assert their independence in an unforgiving frontier.

The Mormon Settlement of Utah Before Leading Up to the Mountain Meadows Massacre

The Mormon settlement of Utah began with the arrival of Brigham Young and thousands of Latter-day Saints in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847. Escaping religious persecution in the eastern United States, the Mormons sought isolation in the Utah Territory to practice their faith freely and build a theocratic society. At the time, Utah was part of Mexico, but the Mexican-American War ended in 1848, making it a U.S. territory and bringing Mormons under American governance.

By the early 1850s, the Mormon population had grown, establishing communities throughout the Utah Territory. They built a network of self-sufficient settlements focused on farming, irrigation, and communal living. Brigham Young was appointed as governor of the Utah Territory in 1850, consolidating Mormon control over the region. Tensions between Mormons and non-Mormon settlers and federal authorities intensified due to mutual distrust of Mormon polygamy, theocracy, and perceived separatism.

As the population of Utah Territory increased, settlers also became more determined to assert their autonomy. The federal government, concerned about potential rebellion and separatism by the Mormons, attempted to expand its influence over the territory. In 1857, President James Buchanan ordered a military expedition to Utah to remove Brigham Young as governor and reassert federal authority, leading to a period of conflict known as the Utah War. The impending federal invasion led to an atmosphere of fear and hostility among Mormon leadership and settlers.

In mid-1857, Mormon settlers had fortified their settlements and prepared for potential conflict with federal forces. Brigham Young had adopted a defensive strategy, calling for local militias to defend the settlements and urging isolation from non-Mormon outsiders. This climate of fear and tension created a volatile situation for emigrant groups traveling through the Utah Territory.

The Baker–Fancher Party Before Reaching Utah Territory

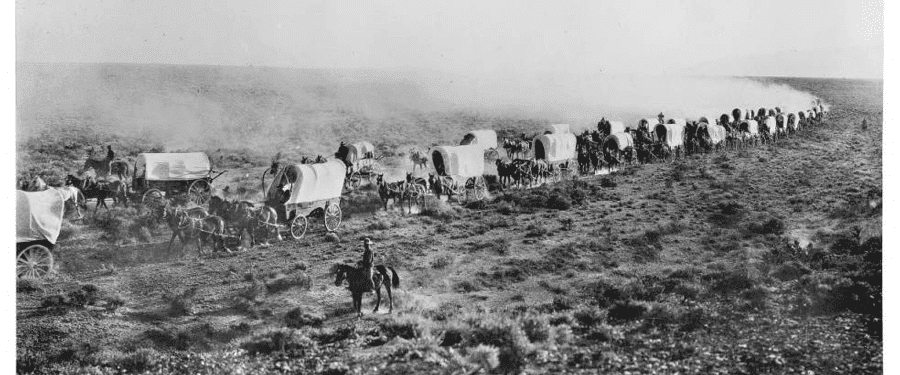

The Baker–Fancher party was composed of four or five small wagon trains of emigrants that had been formed in the northwestern corner of Arkansas, in Marion, Crawford, Carroll, and Johnson counties. In early 1857, several families from this region gathered at Beller’s Stand, near today’s Harrison, Arkansas, to begin their westward trek, planning to make southern California their final destination. At first, the group was known as the Baker train or, sometimes, the Perkins train. The name “Baker–Fancher party” comes from their leader, “Colonel” Alexander Fancher. A veteran of two successful trips to California, Fancher was respected as an experienced and knowledgeable frontiersman.

A typical emigrant group of its day, the Baker–Fancher party was, by most accounts, a relatively wealthy, well-organized, and well-equipped group of travelers. The company was large enough to form a single wagon train, which would keep them together and provide some measure of protection against attacks and accidents on the trail. Fancher planned the party’s route, and his experience gave them confidence in his leadership.

Supplies had to be carefully rationed on the long trail, and the Baker–Fancher party planned to resupply in Salt Lake City along the way, as was common for many travelers on the trail. Families from other states, including several from Missouri, joined the emigrants from Arkansas before the party left on its journey. By the time the group reached the plains in the vicinity of what is today Independence, Kansas, in mid-April, the party had grown to between 120 and 140 people, including children.

In addition to their numbers, the party was notable for its wealth, in terms of both money and goods, for which it was widely known along the trail. Emigrants often bought and sold among themselves while on the trail, and records show that the Baker–Fancher party had a large number of cattle, horses, and other animals. Groups like the Baker–Fancher party were common on the California Trail during the middle decades of the 19th century, seeking to establish a new life in California. This destination became increasingly popular with settlers each year due to the Gold Rush and other economic opportunities.

The group was not long past eastern Kansas when it found itself enmeshed in a political and military situation that was growing increasingly tense and rapidly approaching a boiling point: that of the conflict between Mormon settlers in Utah Territory and the federal government of the United States. The Baker–Fancher party had no way of knowing, as they neared Utah Territory and planned to stop in Salt Lake City to resupply, that this would put them right in the middle of this conflict and on their way to becoming a part of one of the most notorious tragedies of the West.

The Baker–Fancher Party’s Arrival in Utah

The Baker–Fancher party, which had traveled for months across the western frontier, finally arrived in Utah Territory in August 1857. Their destination was southern California, but like many other emigrant groups, the Baker–Fancher party intended to rest and resupply in Salt Lake City before moving on. Tensions were high when the emigrants entered Utah. Federal troops were on their way to the territory, and the threat of war was on everyone’s minds. Mormon settlers were growing increasingly distrustful of outsiders. These tensions would all contribute to the events at Mountain Meadows.

The emigrants were noted as they passed through various Mormon settlements in Utah. In previous years, emigrant groups were usually greeted and traded with by local communities, but in 1857, these relations were strained due to the political situation. There are also reports that the Baker–Fancher party was only able to obtain supplies with incredible difficulty. It seems that Mormon authorities had ordered the settlement’s inhabitants not to engage in trade with the emigrants. The fear that federal spies or saboteurs were in their midst led to this policy, which made it very difficult for the Baker–Fancher party to restock its supplies.

The party continued its journey south through Utah and toward the Mountain Meadows, a lush area where many travelers rested before moving on toward California. Mormon militias called the Nauvoo Legion were on high alert to protect Mormon settlements from any potential threats. As the Baker–Fancher party traveled through the American frontier to Utah, the area was filled with fear and hostility. Their presence was seen as part of a potential federal attack, and tensions rose.

The emigrants reached the Mountain Meadows in early September. Unbeknownst to them, they were soon to become caught up in the escalating conflict between the Mormon settlers and the U.S. government in what would become known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

The First Attack and Encirclement of the Baker–Fancher Party

The Baker–Fancher party continued on their journey, heading 125 miles (201 km) from Corn Creek toward Mountain Meadows. They passed through Mormon settlements, Parowan and Cedar City, each presided over by a Stake President who was also a senior leader of the Nauvoo Legion military district: William H. Dame in Parowan and Isaac C. Haight in Cedar City.

The approach of the emigrant company was met with a series of community meetings among LDS leaders, who were uncertain about the proper course of action given Young’s order of martial law. Some called for using Paiute allies to massacre the emigrants, but the meeting ultimately determined that they would await a response from Young before taking further action. Haight, however, dispatched a secret messenger south to John D. Lee.

In early September, the Baker–Fancher party arrived at Mountain Meadows. The site was well known to emigrants along the Old Spanish Trail as a shared stopping place. The weary travelers intended to rest there for several days before continuing west to California.

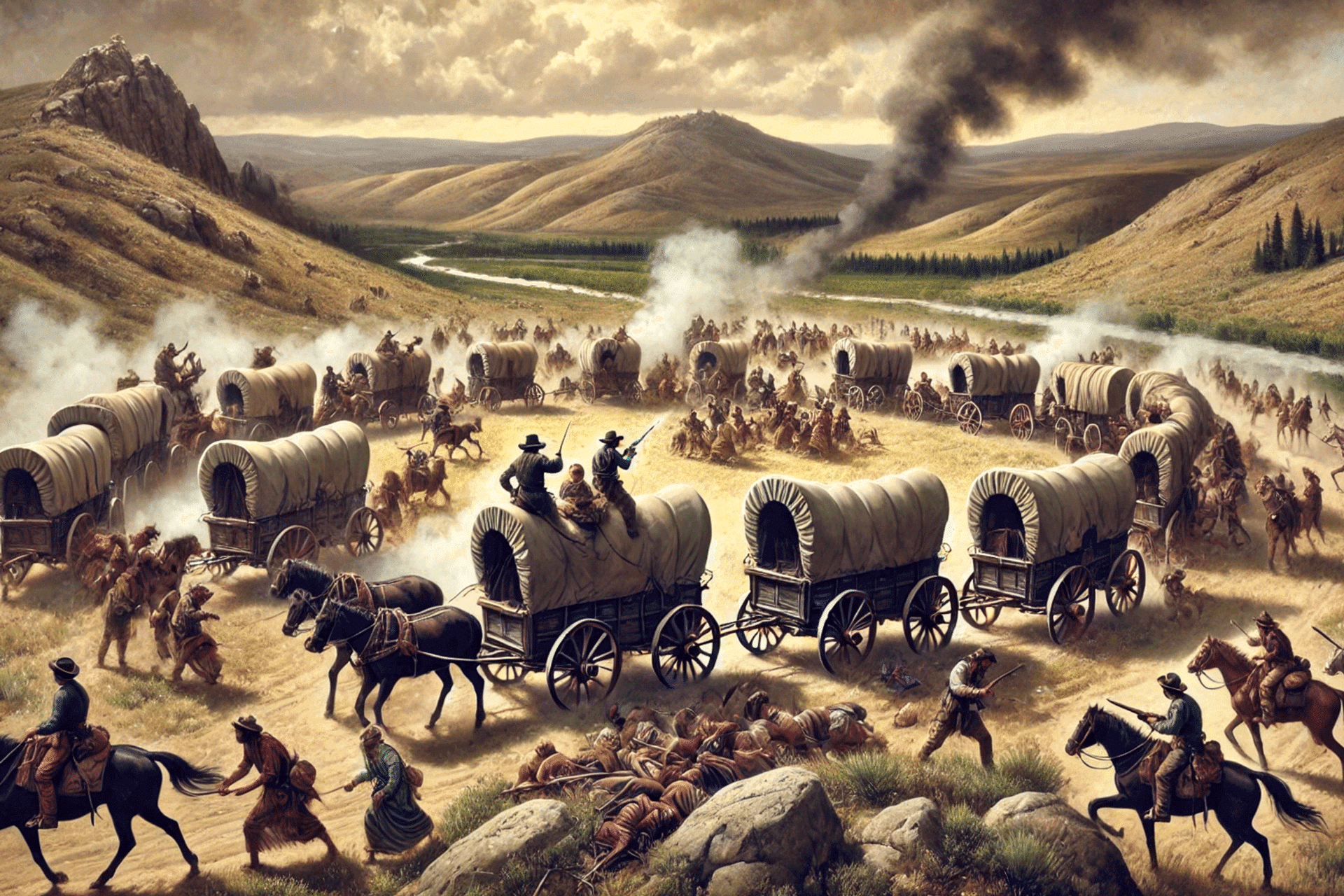

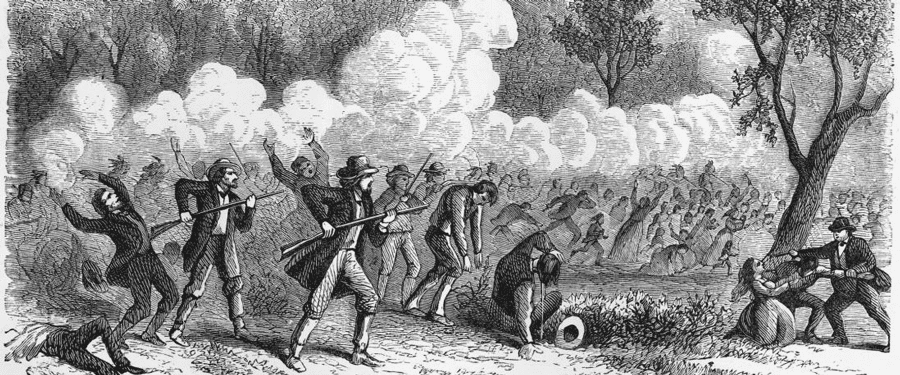

On the morning of September 7, a band of Nauvoo Legion militiamen in Native American disguise, accompanied by a force of Paiute, appeared and suddenly attacked the emigrants. The emigrants circled their wagons and chained the wheels together. Seven emigrants were killed and sixteen wounded during the initial attack, but the emigrants were able to keep the attackers at bay. However, their water and ammunition supplies were soon running low.

After five days of siege, with no fresh water or food, the emigrants were in a grave situation. At the same time, chaos was overtaking the Mormon militia leaders, as a panic set in that some of the emigrants had seen white men among their attackers and might tell. As they worried that word of the events would reach a California settlement before them and the militia had left, the decision was made to slaughter all the emigrants, sparing only the children under the age of seven or eight who were thought too young to remember or testify about what had happened.

Treachery Following the Truce and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

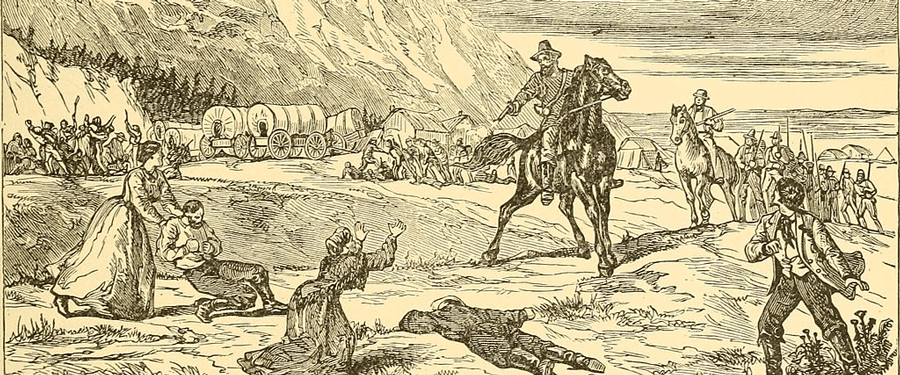

On September 11, 1857, after five days of siege, two militiamen approached the Baker–Fancher party under a white flag of truce, one of them being John D. Lee, a Mormon militia officer and Indian agent. Lee told the emigrants that he had made a truce with Paiute warriors. He promised safe passage to Cedar City under Mormon escort, but only if the emigrants surrendered their livestock and other supplies. Exhausted and facing a severe winter, the emigrants agreed, not realizing they had been tricked and that this was only a prelude to the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

The emigrants were led out of their fortifications. The men were separated from the women and children and put in pairs with militiamen dressed as their escort. At a prearranged signal, the militiamen turned and shot the emigrants; some other members of the militia ambushed the women and children from covered positions. Seventeen children were spared because they were considered too young to have witnessed or remember the events. At least one girl, apparently judged to be old enough to be able to testify to what had happened, was shot to death before the children’s eyes to prevent her from identifying her murderers. The surviving children of the Mountain Meadows Massacre were taken into Mormon families.

Eventually, the U.S. Army recovered the surviving children present at the Mountain Meadows Massacre and returned them to their relatives in Arkansas. Descriptions from the time indicate that the children were half-starved, filthy, and in poor health as a result of their captors’ indifference and neglect. Captain James Lynch’s 1859 report stated, “I found the whole party in a wretched condition, destitute of clothing, half-starved, and loaded with vermin.” The survivor stories of the massacre’s orphans are some of the most haunting of the event.

Livestock and personal property of the Baker–Fancher party were divided among the local settlers or sold at auction. Some of the children who had survived later recognized pieces of clothing and jewelry that had belonged to their mothers and sisters among Mormon women in the community. Brigham Young may have sent the leaders of the militiamen a letter of advice suggesting that the emigrants be allowed to pass unmolested. Still, it was sent too late, not reaching them until two days after the massacre.

Investigations and Prosecutions for the Mountain Meadows Massacre

The first official inquiry into the Mountain Meadows Massacre was led by Brigham Young in 1857, immediately following the attack. On September 29, 1857, Young interviewed John D. Lee and Lee corroborated the story blaming local Native Americans for the massacre. In 1858, Young submitted a report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs reiterating that Lee and a band of Native Americans were responsible. The first federal investigation that made any headway into the affair was not opened until 1859. Jacob Forney and Major James Henry Carleton opened inquiries in 1859. Carleton’s report, based on his physical examination of the massacre site and interviews with local settlers and Paiute leaders, implicated the Mormons as responsible for the attack.

The army officer described finding women’s and children’s bones strewn over Mountain Meadows, some with children’s remains still seemingly in the arms of the bodies of their mothers. He buried the remains of the dead and raised a cairn and cross at the location of the final massacre. He submitted a report to Congress that concluded the killings were a “heinous crime” in which local Mormon leaders and church elders were both culpable.

Jacob Forney, who had spirited away several of the children from Mormon families who had captured them, also concluded that the Paiutes could not have committed the massacre unassisted. In 1859, Judge John Cradlebaugh impaneled a grand jury in Provo, Utah, but it refused to issue indictments.

Prosecutions for the massacre would resume a decade later in 1871, when Philip Klingensmith, a militia member who had since left the LDS Church and moved to Nevada, submitted an affidavit against some of the principal players. In 1874, indictments were issued against John D. Lee, William Dame, and several others. Lee was arrested, and the others fled or went into hiding. Brigham Young excommunicated both Lee and Isaac Haight from the LDS Church in 1870. Klingensmith testified against the others in exchange for immunity.

John D. Lee was tried in 1875, but the first jury could not reach a verdict. A second trial, in 1876, before an all-Mormon jury, resulted in Lee’s conviction. On March 23, 1877, John D. Lee was executed by firing squad at Mountain Meadows. Before his death, Lee proclaimed that he had been made a scapegoat to protect others who had participated in the attack. Brigham Young would later state that the execution of Lee had been just, but that it was not enough to atone for the crime.

The Legacy of the Mountain Meadows Massacre

The public reaction to the Mountain Meadows Massacre was one of horror and condemnation when the news spread. The event intensified anti-Mormon sentiment among the general American public, with widespread blame placed on the LDS Church for the attack. The federal government also became more suspicious of the Mormon settlements in Utah and increased efforts to establish stronger American control over the Utah territory. Legal ramifications were limited, but the massacre would have a lasting impact on the history of westward expansion and the relationship between settlers and Native Americans.

The massacre harmed the perception of the Mormon community as well. Brigham Young and other church leaders were criticized for their alleged involvement and the perceived inflammatory rhetoric leading up to the attack, even though Young had written a letter warning against harming the emigrants. Over the years, memorials have been erected on the site of the massacre to commemorate the victims. The first memorial was constructed by Major Carleton’s troops in 1859. Over time, other monuments and plaques have been added, and today, the Mountain Meadows Massacre site is recognized as a National Historic Landmark. Commemorative events are also held annually to remember the victims.

The Mormon Church has also made efforts to distance itself from the massacre and the actions of those who were directly involved. In 2002, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints published a detailed study titled Massacre at Mountain Meadows. The publication provided a comprehensive look at the events and context of the massacre, acknowledging the role of local Mormon leaders while also placing the incident in the broader context of the tension and conflict at the time. This was a significant move by the LDS Church to offer transparency and distance itself from the individuals responsible for the tragedy.

The Mountain Meadows Massacre is remembered as a tragic and senseless event, and the impact of the massacre on the collective memory of the American public and the Mormon community continues to be felt. Memorials and historical research have contributed to ongoing efforts to honor the victims and understand the complex causes of this horrific act. The story of the Mountain Meadows Massacre remains a stark reminder of the challenges and violence that characterized frontier life in the American West during the period of westward expansion.