The Haitian Revolution and the First Black Republic

The Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) was among the most radical and far-reaching revolts in modern times. What began as the largest slave revolt in the history of the Americas developed into a revolution that defeated European imperial powers and abolished a genocidal plantation economy. Over the course of thirteen years, enslaved women and men revolted against one of the richest colonies in the Atlantic world. In 1804 they declared independence and named their country Haiti. Witnesses were shocked: the revolt “astonished the world”.

The Haitian Revolution remains the only successful slave revolt in history on a large scale. Other revolts failed, but Haitian slaves bested the forces of France, Spain, and Britain. The revolution transformed the Atlantic world. Haiti abolished slavery in the colony and established the world’s first independent Black republic. In doing so, Haiti redefined what people around the world understood about freedom, empire, and human rights. It changed not just one island. It changed the world.

Saint-Domingue Before the Haitian Revolution

Saint-Domingue was France’s most profitable and wealthiest colony before 1791. The colony produced sugar, coffee, indigo, and cotton on large plantations primarily for export to Europe. By the end of the 18th century, Saint-Domingue accounted for half of the sugar and coffee consumed in Europe. French shipowners, merchants, and investors accumulated great wealth through trade with the colony. The colony was one of the richest in the world, and one traveler called Saint-Domingue “a jewel of the Antilles.”

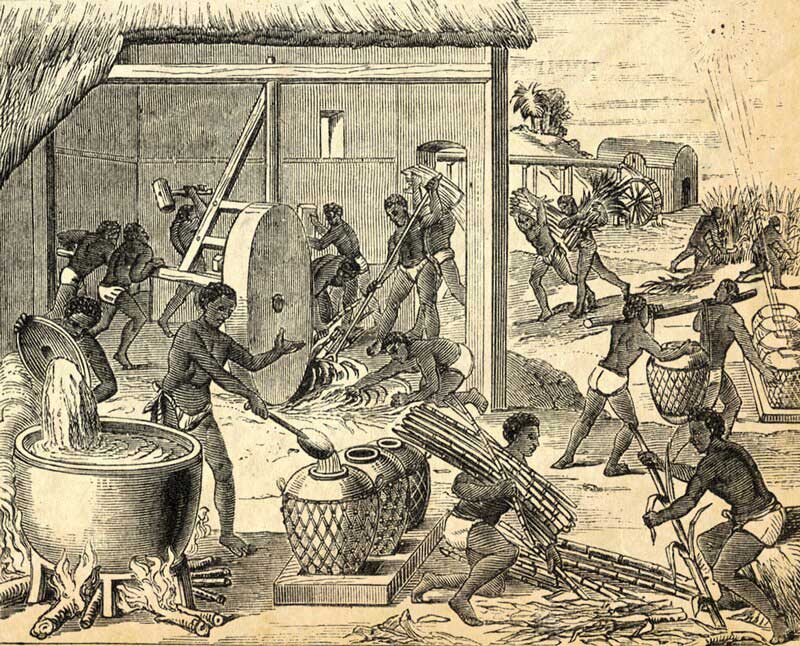

It is estimated that slaves comprised nearly ninety percent of the population. Sugar, coffee, and wealth were produced through grinding schedules, near-constant discipline, physical violence, and brutal treatment. Mortality rates were high due to overwork and punishment, as well as tropical diseases. Many enslaved Africans had only recently arrived from their homeland via the harrowing Middle Passage. Planters maintained brutal working conditions because the death rate far exceeded births in the population of enslaved workers. Few people, enslaved or free, felt completely secure in their status.

In Saint-Domingue’s class society, position in the social hierarchy was determined by race and status. At the top of colonial society were wealthy white planters and officials sent by the French colonial authorities. French administrators and their troops were stationed on the island to maintain the lucrative status quo.

In the middle were free people of color, who were often mixed-race descendants of French men and enslaved women. Many were quite prosperous and owned property (and sometimes slaves), but were denied political rights. Enslaved Africans were at the bottom of colonial society. Segregation laws were strictly enforced. Tensions could erupt from small disturbances in the social hierarchy. White colonists were reluctant to believe that society was united at all.

Revolutionary sentiment came to Saint-Domingue from two directions: the ideas of the Enlightenment, and the outbreak of revolution in France. Enlightenment ideas spread through books and periodicals. Newspaper boys brought news of these ideas to colonial Saint-Domingue from the port cities in France. On both sides of the Atlantic, free people of color began agitating for the rights promised to them in France. Enslaved laborers also became aware of and took interest in debates about the nature of liberty and citizenship. “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.” The words of the Haitian Revolution would prove incendiary in Saint-Domingue.

The Spark of 1791

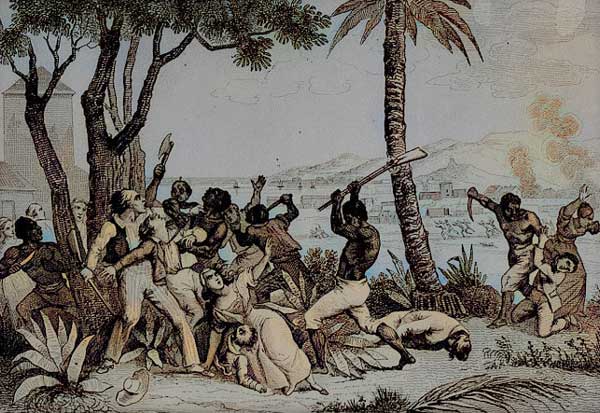

In August of 1791, tensions boiled over. The first uprising occurred on the northern plains of Saint-Domingue, where many of the wealthiest plantations were located. Armed slaves attacked one estate after another. They set fire to sugar fields and to mills where sugar cane was processed. Hundreds of plantations burned within days. One French witness described “the horizon was red with fire.” Slave rebels organized the insurrection and worked together to attack the white colonists who had oppressed them for generations.

The ceremony at Bois Caïman has been mythologized as the moment the enslaved of Saint-Domingue formally decided to break their bonds. As the story goes, voodoo priests led enslaved laborers in a wooded clearing and had them swear an oath of unity and revolt. A leader among them, often said to be Dutty Boukman, proclaimed that they no longer believed in the “god of the whites who caused their tears and suffering” and encouraged the people to believe in themselves.

The details of the ceremony are likely exaggerated or altered, but serve as a powerful image of the spiritual and political strength throughout the rebellion. The ceremony marked a fusion of Vodou religion with a movement to resist slavery at all costs.

News of revolts in the north spread like wildfire. Houses were burned, cane fields were torched, and animals were killed throughout northern Saint-Domingue. Some plantation owners escaped inland toward the northern cities of Cape Français and Porto-Principe, while others hanged themselves or were killed by their own slaves. The revolt was not simply an outburst of rage but a widespread attack on the institution of slavery. Sugar mills ground to a halt, and fields once busy with the colony’s most lucrative commodity lay abandoned and burnt. Hierarchies that colonists had built over the years began to collapse in a matter of weeks.

Colonial leaders could do little to quell the uprising. Militias were assembled but proved ineffective against the tactics of insurgent slaves. White colonists from different political factions argued in town meetings about how to address the crisis. Members of the free people of color were demanding equal rights as news of the French Revolution reached Saint-Domingue. Colonial leaders were divided on how to proceed as the insurgency grew bolder by the day. Residents lost faith in the government’s ability to control the situation.

News of the revolt had also reached France, which had been in the midst of the French Revolution since 1789. Officials in the National Assembly scrambled to find solutions, but no clear decision was made on what to do with the colony. Some believed it could be negotiated, while others advocated military suppression. Time was lost as colonial officials bickered back in Paris. The French government’s power seemed weak as colonial society fell into chaos.

1791 was the beginning of the end for colonial control. Although the rebellion began as a coordinated attack on the wealthiest plantations in the north, it did not take long for the violence to escalate. Armed groups began to form around leaders who would become the faces of the rebellion. New alliances were created and old ones dismantled as more events unfolded. The empire, maintained through decades of domination and violence, would take more than a few weeks’ upheaval to rebuild. In August 1791, enslaved people began fighting for their freedom and would not give up.

Leadership and the Rise of Toussaint Louverture

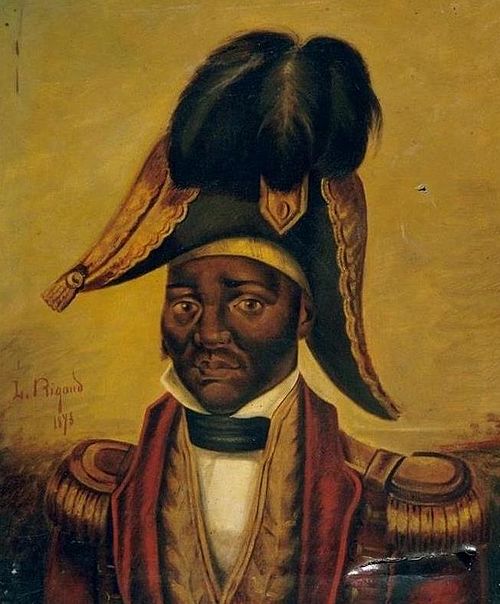

One of the leaders who rose to prominence in the fighting was Toussaint Louverture. Born into slavery but later freed, Toussaint had educated himself enough to read and understand the Enlightenment ideals of freedom and rights that had begun circulating during his lifetime. He joined the early slave revolts and impressed others with his organizational talents. French administrators remarked on how calmly authoritative he seemed, even in times of crisis. Louverture slowly gained command of the rebels and became the effective leader of the revolutionary forces in the colony.

Events on the world stage aided Toussaint’s ascent. France, Spain, and Britain all intervened in the conflict over Saint-Domingue and attempted to dominate the colony for themselves. Spain entered the war on the side of the rebels early on, providing weapons and commissions to many leaders. Toussaint accepted a commission as a Spanish officer. However, allegiances were easily broken. In response to the foreign invasion of the colony, France abolished slavery there in 1794. Toussaint promptly betrayed his Spanish allies and threw in his lot with France, declaring liberty and not empire would guide his cause.

In one famous letter, Toussaint proclaimed that he “no longer recognizes whites as leaders.” He fought now not for colonial autonomy but to expel the Spanish, British, and remaining French administrators from the island. Toussaint was greatly helped by France’s Emancipation Decree. Desperate to hold onto their most profitable colony, France had officially freed all enslaved people there.

This positioned them against both Spain and Britain, who continued to support slavery in their own American territories. Louverture had little difficulty convincing former rebels to follow him against foreign powers; he could now offer them freedom as well as victory. Britain was driven out of Saint-Domingue militarily by organized Black troops under Louverture’s command.

Louverture consolidated power through a mix of politics and violence. He signed peace treaties with the remaining rebels and had them executed after they surrendered. Plantations were slowly brought back under production using paid workers. Although Louverture cooperated with France and allowed French administrators to return to the colony, he never fully submitted to their rule. He wrote letters to French officials, promising allegiance to the French Republic but refusing to be ordered about. Louverture even wrote that if France attempted to re-enslave the population of Saint-Domingue, he would “plant the tree of liberty” once more. In many ways, Louverture maintained his power through strength and threats.

Louverture defeated his rival generals in 1801 and took control of nearly all of Saint-Domingue. He crushed rebellions and chased out the last of the Spanish and British forces. The colony would no longer be dictated by remote imperial administrators. Toussaint publicly maintained he was only fighting on behalf of France. In reality, he had the most power and placed his administrators in key positions. Order was enforced after a long, chaotic period of revolt.

In 1801, Louverture promulgated a constitution for the colony. It reiterated the abolition of slavery and appointed Toussaint as governor for life. It promised an allegiance to France but removed France’s power over the colony. The constitution made clear that Saint-Domingue would act independently of France whenever its interests were threatened. Leaders in Paris, including Napoleon Bonaparte, viewed this as an affront to their power.

Napoleon’s Intervention and Renewed War

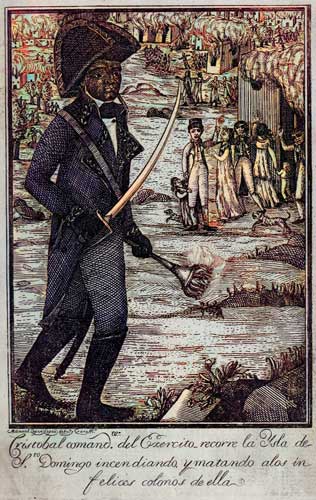

In response to the loss of France’s wealthiest colony, Napoleon Bonaparte organized an expedition to Saint-Domingue in 1802. Although slavery had been abolished by France in 1794, colonial interests hoped to restore plantation agriculture. Napoleon wanted to restore imperial authority over the colony and its profits. He stated that emancipation would not be reversed. However, news from other colonies hinted that France may have other intentions. French soldiers took control of the island in strength and began disarming the inhabitants. Word quickly spread through networks of former revolutionaries. They feared their freedom was at risk once again.

French leaders initially attempted diplomacy alongside military action. Many colony leaders waited and watched to see if France would restore slavery. Toussaint Louverture was one leader who negotiated. He hoped to work with the French to maintain some degree of autonomy in the empire. French leaders, however, had other ideas. In June 1802, Toussaint was invited to a meeting and imprisoned. He was exiled to France and incarcerated in Fort de Joux. He died there the following year.

Before his death, Toussaint is quoted as saying: “In overthrowing me, you have cut down in Saint-Domingue only the trunk of the tree of liberty.” Slavery was officially abolished in Saint-Domingue, but trust had been broken. Rumors spread that slavery had been re-instituted in Guadeloupe. Black leaders feared that negotiating with France would lead to slavery once more. Support for negotiating with the French weakened. The war would no longer be about autonomy, but independence.

The renewed conflict was vicious, and both sides attacked with ferocity. French reprisals included executions and village burnings. Former revolutionaries fought back fiercely against the French army. Former revolutionaries had unified under a common goal of stopping slavery. What was once a revolution for autonomy had become a fight for survival. The violence traumatized much of the island population.

Illness soon became as lethal as warfare itself. Yellow fever ravaged the French army, claiming the lives of thousands of men unaccustomed to the tropical weather. Entire legions were debilitated or decimated. General Leclerc even fell victim to disease. They were reinforced with new troops who met similar consequences. “The climate was the real general of the blacks,” one historian noted. Slowly but surely, the French expedition unraveled with disease and constant resistance.

Amid this renewed war of independence, Jean-Jacques Dessalines emerged. Formerly Toussaint’s lieutenant, Dessalines had lost faith in the promises of the French. He organized and led troops during the fight for independence. Dessalines was resolute and focused on the war effort. Former slaves fought to gain their freedom at all costs from France, which was jaded by their betrayal. Under his leadership, soldiers were dedicated to the mission of independence.

By November of 1803, the French were tired. Dessalines continued to push French troops until the climactic battle of Vertières. The second war of Haitian Independence ensured the irreversible transition to independence and created the first black republic.

Independence in 1804

By November 1803, French resistance in Saint-Domingue had ended. Years of fighting, yellow fever, and native armies dismantled Napoleon’s forces. At the Battle of Vertières in late November 1803, the French suffered their final defeat. French General Rochambeau surrendered weeks later. Napoleon’s dream of reclaiming the colony had failed. What started as a mission to reassert power ended in defeat. France’s greatest colony in the Americas had fought and won independence. For the first time in history, enslaved people had defeated a European power in open combat.

On January 1, 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines read Haiti’s declaration of independence in Gonaïves. Haiti, taken from the Taíno word Ayiti, meaning “land of mountains,” was the new name of the colony. The declaration moved away from the colonial title of Saint-Domingue and referenced the indigenous past. In it, Dessalines promised that Haiti would “never again be the province of any kingdom.” Independence was freedom; enslaved people were no longer subjects of a foreign power after the Haitian Revolution.

Dessalines quickly became governor-general and later crowned himself Emperor Jacques I. His power came from his control of the army and support from veterans. However, independence was just the beginning of the nation’s troubles. The economy of Saint-Domingue was devastated by years of war. Plantations were destroyed, international trade was disrupted, and France refused to acknowledge Haitian independence. Other global powers feared the example Haiti set and would not recognize Haiti as an independent nation for decades. Haiti faced potential isolation.

Haiti’s leaders feared foreign invasion. Slaveholding powers viewed black independence as a threat to their own countries. The United States and European nations would not establish diplomatic relations with Haiti. Dessalines argued that only through unity could Haitians ensure their independence. To maintain independence, Haiti would have to become agriculturally self-sufficient again. However, Dessalines did not want to return to the repressive conditions that preceded the Haitian Revolution. Freedom was imperative, but how could that be balanced with production?

Dessalines also faced domestic strife. Some Haitian leaders opposed the idea of a strong central authority. Regional autonomy was preferred by others. The army was strong, but political opponents lingered. In 1805, Haiti promulgated its first constitution, which declared all Haitians to be Black. The Constitution promised that slavery would be abolished forever. This decision was driven both by pride at Haiti’s accomplishments and fear of the international response.

Independent Haiti was not without conflict. Dessalines was a harsh ruler, and many opposed his policies. When he attempted to resume plantation production through military force, many opposed him. Dessalines was assassinated by political opponents in 1806. Northern and southern governments soon divided control of Haiti. Even amid civil war and isolation, Haiti maintained its independence.

Global Shockwaves

News of the Haitian Revolution terrified slaveholders throughout the Atlantic world. Reports that enslaved Africans had overcome a European army alarmed slave societies from Bahia to Barbados. White plantation owners in Jamaica and Georgia alike scoured newspapers with trepidation. Rumors spread even quicker than news. Authorities increased patrols and restricted public meetings in cities like Charleston and Havana. Bondage could be overthrown through violence. The revolt reframed what was imaginable for the enslaved.

Nations reliant on slavery clamped down on their own citizens. Governments restricted freedom of movement, made literacy illegal, and allowed fewer public assemblies. American lawmakers in the South cited Saint-Domingue when arguing for more restrictive slave codes. One British commentator described Saint-Domingue as “a volcano whose lava might spread.” Slaveholders throughout the Americas feared the example would inspire similar rebellions. In 1799, a conspiracy was discovered among slaves in Gasparilla, Florida. Although planned several years in advance, leaders of the revolt had met secretly and discussed plans that included familiar ideas they “learned from the blacks of Haiti.”

American leaders would not officially recognize Haitian independence until 1862. Although Americans traded with Haiti behind closed doors, many did not want to acknowledge a Black republic forged in revolt. They worried that accepting Haiti as a nation would inspire similar rebellions at home. European powers felt similarly. In 1825, France threatened to invade Haiti unless the new nation agreed to pay an indemnity. Leaders sought to prevent the message from spreading by isolating Haiti.

International isolation contributed to Haiti’s economic struggles. Without partnerships, Haiti lacked strong economic ties with powerful countries. France’s embargo on Haiti was a diplomatic quarantine that could only be solved if France would recognize Haiti’s independence, but required the new nation to pay millions of pounds in compensation. Still, Haiti persisted. The mere existence of Haiti devastated racial assumptions about who could govern themselves. Surviving became an act of defiance.

Abolitionists used Haiti as a rallying cry in Britain and the American North. Reformers argued that slavery was immoral and politically unsustainable. They used Haiti as an example of Black people governing themselves independently of Britain. Abolitionists wrote about Haiti in the context of slavery’s violence. If emancipation led to violence, some abolitionists argued it was better to release people from bondage. The Haitian Revolution did not instantly abolish slavery, but it did change the conversation about the institution. Abolition became linked with national security.

Revolutionary leaders in Latin America were also influenced by Haiti. Simón Bolivar of Venezuela would later receive assistance from Haiti when fighting for independence. He promised to end slavery in South America. The Haitian Revolution helped connect the abolition of slavery to struggles against European colonialism. It showed colonized people and enslaved Africans that they could demand independence and freedom from bondage at the same time. The influence of the revolution can be seen around the world.

Haiti exposed the hypocrisy of nations committed to ideas of liberty. America and European powers debated hypocritically over whether Haiti should be a free nation. They championed freedom and order while suppressing the will of people of color. The Haitian Revolution transformed the global conversation about freedom. The revolt in Saint-Domingue forced the world to redefine what liberty meant for all people.

Internal Struggles and External Pressures

Independence did not solve Haiti’s problems. Years of fighting had destroyed plantation buildings, towns, and roads. Fields went untended, commerce dwindled, and trained laborers were few. Haiti’s economy suffered as soon as independence was declared. National leaders attempted to balance ideals of liberty with economic necessity. Some politicians hoped to keep workers on the plantations, overseen by military commanders. Maximizing exports would help rebuild the nation’s wealth. Others were content with smaller plots of land and greater autonomy. Former slaves had differing ideas about the new republic.

Freedom also meant political uncertainty. In 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines proclaimed himself emperor of Haiti. He was killed two years later, which devastated the nation’s political stability. Rival governments formed in northern and southern Haiti. Henri Christophe crowned himself King Henry I in the north. A republic under Alexandre Pétion took power in the south. Both men felt they were Haiti’s rightful leaders. The cultural and political divisions between the two regions grew deeper.

The economy of the north was rebuilt through harsh discipline. Christophe focused on agriculture, attempting to maximize production. He also invested in buildings that demonstrated strength and order. Fortifications like the Citadelle Laferrière served both practical and motivational purposes. Christophe feared foreign invasion, so he kept Haiti’s army ready for conflict. The South redistributed land into smaller farms that were easier for the formerly enslaved population to maintain. In general, the north maintained large export enterprises while the south did not.

The unstable compromise began to crumble under international pressure. In 1825, France offered to recognize Haiti as an independent nation. In exchange, Haiti would pay 150 million gold francs to French creditors. Former slaveholders had lost “property” during the revolution, and they needed to be compensated. French recognition meant military security, but it came at a high price. Haitian politicians knew that refusing France would invite invasion. They agreed to pay the indemnity and secure France’s goodwill.

French banks loaned Haiti the money in exchange for repayment with interest. The Haitian government bore a heavy financial burden for many generations. Debt payments consumed national funds that could have been used to strengthen public infrastructure. Schools, roads, newspapers, government buildings, and more had to be funded by the people. “The infant republic was forced to buy its freedom a second time,” one historian observed. The indemnity harmed the Haitian economy and fueled political infighting.

Hatred between the North and South mellowed after several years. By the 1820s, Haiti had officially been reunited. But leaders were unable to develop stable political institutions. The Haitian Revolution had left the country weary and its leaders defensive. Government leaders faced constant coups and broken alliances. For many Haitians, balancing freedom and authority proved to be remarkably difficult.

Historical Memory and Legacy

The Haitian Revolution is one of the greatest examples of black resistance in modern history. The enslaved didn’t ask for amendments to their situation. Instead, they toppled an entire slave society and formed their own nation. In 1804, the founding of Haiti sent a clear message to the world that freedom was not the exclusive domain of white Europeans. We had “dared to be free”, declared one revolutionary pamphlet. People on both sides of the Atlantic would dare to be free as well, looking to Haiti as proof that the fight was worth it.

Haiti served as a beacon of hope to blacks worldwide. The mere existence of a free Black republic proved that enslaved people could one day govern and organize themselves. Black activists and abolitionists in the 19th century regularly referenced Haiti’s example. They had liberated themselves without outside assistance. What started in Haiti shook the foundations of racist ideology.

But in the West, Haiti was often silenced. European and American textbooks downplayed the rebellion or depicted it as bloody disorder. Slaveholders had no reason to amplify the voice of the enslaved. Political powers throughout the Atlantic feared the success of the revolt. It took center stage for a time, but many authors relegated it to the margins.

Racial prejudice played a significant role in its exclusion. The Haitian Revolution forced liberal intellectuals to question the validity of their arguments. After all, how could they champion the rights of men and women while upholding slavery? Instead, they twisted the narrative of the rebellion to fit their biases. The historians ignored the voices of Haiti’s revolutionaries as much as possible.

Thankfully, modern historians have recognized Haiti’s significance. Scholars now consider the Haitian Revolution one of the most important geopolitical events in modern history. The Atlantic World would never be the same because of Haiti. It changed the course of trade, colonialism, and debates on race and equality. The impact of Haiti is impossible to understand without studying the Great Haitian Revolution.

What’s more, historians are discovering the intellectual power behind the revolution. The Haitians challenged the world’s understanding of universal rights. Instead of stopping at just proclaiming that all men are created equal, they abolished slavery forever. In doing so, they redefined what liberty meant to everyone.

To this day, Haiti’s great revolution inspires folks around the globe. Haiti has endured a lot since 1804, but its revolutionary spirit lives on. The Haitian Revolution serves as an example and a warning. It shows us that if people have the will to fight for their freedom, they can change the world.

A Revolution That Redefined Freedom

There is no story quite like Haiti’s revolution in history. It was the only slave uprising that successfully established an independent nation. Slaves did not just resist; they defied an empire and founded a state. In 1804, Haitians proclaimed themselves “either to live independent or die.” Neither word was an exaggeration. The Haitian Revolution was one of the most radical ruptures in the age of revolution.

Its impact was immediate and global. Abolishing slavery in Saint-Domingue dealt a massive blow to the Atlantic plantation economy. Slave owners trembled at its example. Abolitionists rallied around its achievement. France’s colonial ambitions were dealt a crippling blow. Even commercial networks adjusted to compensate for the loss of Saint-Domingue’s production. Slavery survived, but no longer seemed inevitable. Haiti changed conversations about abolition for generations.

The Haitian Revolution looms large over modern concepts of freedom and equality. This new sense of freedom mattered because it was tangible. Haiti forced conversations about the inconsistencies of human rights when it came to race. Its legacy lives on for those who continue to insist on their humanity in the face of oppression. Haiti teaches us that freedom is never given. It is won.