The Maori Musket Wars and the Transformation of New Zealand

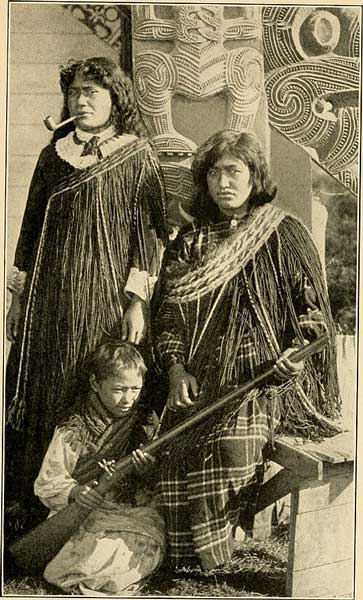

The Māori Musket Wars were a series of inter-iwi conflicts between Māori that occurred from around 1807 to 1845. After muskets were introduced to New Zealand by European traders and whalers, the adoption of firearms and their use in inter-tribal warfare caused enormous changes in power dynamics between the island’s natives.

Groups that had access to muskets had an advantage over those that didn’t, and this changed the nature of warfare from that fought with earlier pre-muskets weapons. It is estimated that over 40,000 Māori died in these conflicts and that Māori demographics, including migration and land acquisition, were massively affected by them. As a consequence of the massive social and political changes that resulted from these wars, missionaries arriving in New Zealand described the country as “desolate and empty”.

Background: Pre-Musket Māori Warfare

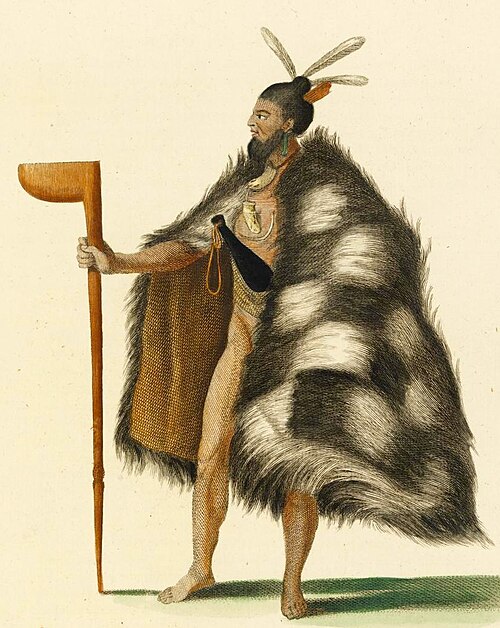

Pre-Musket Māori warfare was characterized by deeply ingrained traditions and practices honed over generations. Battles were fought with traditional weapons like the taiaha (wooden staff weapon for striking and parrying) and the patu (short hand club, often made of stone or greenstone). Warfare was highly organized and ritualized, with close-quarters fighting and emphasis on individual skill, agility, and bravery. Villages were often fortified into pā (fortified hilltop or ridge-top settlements with palisades, earthworks, and ditches) providing strategic defensive positions against attackers.

Warfare played a significant role in Māori society beyond the battlefield, as it was also a means to gain mana (prestige, influence, authority). Victory could increase a chief’s mana and bring honor and respect to his people, while defeat risked diminishing his authority and weakening his tribe’s position.

Another important cultural principle was utu (reciprocity or balance), which meant that if an insult was made, if a person was killed or if something was lost, then utu had to be paid to restore balance. This could involve war or raids to punish the offending group, re-establish honor, and deter future aggression. Thus, conflict was not random but deeply embedded in inter-iwi relationships, with implications for status and influence in the region.

Warfare was also a means for iwi (tribes) to acquire resources, land, and captives, but also a way to maintain dominance and reputation within the region. Successful warfare brought prestige to a chief and raised the status of his people, while defeat risked loss of authority and weakened security. Raids were often quick hit-and-run tactics to exact punishment or show strength, while larger battles would be fought more strategically. Captives could be enslaved, adopted into the victor’s community, or sometimes used in human sacrifices, emphasizing the high stakes of warfare.

European contact in the late 18th century began to influence Māori warfare. Ships of traders, whalers, and explorers provided new materials like metal tools and weapons, which were quickly incorporated into Māori society and warfare. Iron and steel replaced stone for making patu and spear heads, making these weapons more effective. The Māori’s enthusiasm for trade also created new means for iwi to gain status by becoming important intermediaries for European goods and trade access. These changes would accelerate dramatically with the arrival of muskets in the early 19th century, but the seeds of this transformation had been sown in these early encounters.

The early contact period was a time of both opportunity and risk. European goods could enhance traditional practices, but they could also create imbalances between iwi with access to these materials and those without. These initial contact events set the stage for the dramatic transformation of Māori warfare with the widespread adoption of firearms and the coming of the Musket Wars.

The Arrival of Muskets

Muskets began to arrive in Aotearoa (Māori name for New Zealand) from the late 18th and early 19th centuries through trade with European whalers, sealers, and merchants. The Ngāpuhi, a northern iwi, were among the first to acquire these new weapons. Chiefs like Hongi Hika saw the potential of the musket and made it a priority to secure large quantities through trade, exchanging food, flax, and timber in return. By 1818, Ngāpuhi war parties were taking muskets on campaign, and this new advantage was swiftly decisive against rivals who had not yet obtained firearms.

The arrival of firearms began to create an extremely imbalanced relationship between iwi. Armed warriors could strike with impunity- killing at a distance before traditional warriors could close with taiaha or patu. To redress the balance, iwi across the country began trading with Europeans as quickly and as heavily as they could, sometimes going to great lengths to procure firearms both to maintain their mana and to balance utu.

The first campaigns made clear just how game-changing these new weapons would be. In 1822, Ngāpuhi warriors attacked Matakitaki pā, a fortified village in the Waikato region. As the defenders were not accustomed to musket fire, they panicked when volleys ripped through their ranks, and chaos reigned as the pā was overrun. Hundreds were killed in the retreat, and the whole affair served as a clear warning of what was to come for any iwi unprepared to face firearms. It was made clear that traditional fortifications and tactics would no longer be enough to survive.

With the spread of muskets, conflict increased across the country. Iwi that had been previously unassailable through their numbers or formidable defenses suddenly found themselves at a disadvantage. Groups without firearms found themselves displaced, enslaved, or even destroyed, and often driven from ancestral lands. The wars became a never-ending cycle of conquest and reprisal, utu requiring vengeance, and muskets providing the means to escalate violence to new heights.

The introduction of muskets marked the beginning of a new era of warfare for Māori. What began as trade goods began to change the political and cultural landscape of Aotearoa. With every iwi vying to obtain firearms, the balance of power was turned on its head again and again, leading to decades of bloody and destructive conflict that would come to be known as the Musket Wars.

Course of the Musket Wars

As more iwi acquired muskets through trade, the Musket Wars became more widespread, eventually spreading into the North Island and even as far as Te Waipounamu (the South Island). The utu cycle meant that no campaign went unanswered. A response to an attack was expected. As a result of this, and through to the 1830s, the wars became a nationwide affair with most iwi involved.

Ngāti Toa, driven south under pressure from their Tainui and Tūhoe rivals, made repeated incursions over the Cook Strait to carry out large scale raids in the South Island. Te Rauparaha and his warriors successfully fought many battles in the far south. Their destabilising raids through the upper South Island forced many settled iwi to either live in exile in swampy areas, or under the rule of the invader.

The Battle of Mokoia in 1823 illustrated the scale of death and destruction musket warfare could cause. A Ngāpuhi war party invaded Mokoia Island, in Lake Rotorua, a heavily fortified pā of Te Arawa. Mokoia had a highly defensible site, but it was no match for the devastating volley of musket fire. Shots rang out across the island, and as the warriors scrambled from their shelters, they were cut down. Ngāpuhi warriors then rushed in and quickly overran the pā.

Many defenders were killed outright, and others were captured and carried off the island as slaves. Memories of those who survived the battle speak of the fear of being attacked by an enemy whose weapons could quickly cause the demise of those who had put their faith in their pā’s defences and their close-combat skills.

As at Mokoia, many other campaigns were fought across Aotearoa. Defensive pā that were once considered safe now needed to be improved if they were to stand a chance against volleys of musket fire. Raids of this kind were capable of driving thousands of people off their land. Iwi boundaries across the country were redrawn as the victorious moved to take over the lands of those they had defeated. Some iwi were completely destroyed, while others increased their numbers by absorbing slaves and captives.

By the 1830s, the wars had spread nationwide, with most iwi directly or indirectly involved at some stage. While the acquisition of muskets by most iwi evened out the balance, the utu cycle ensured that the violence continued, as each attack had to be answered by another.

The End of the Musket Wars

By the late 1830s, several factors were leading to the slow end of the wars. One of the primary factors was the increased availability of guns. As more iwi acquired access to firearms, the Musket Wars became less lopsided. As all parties were able to cause significant damage, the relative benefit of aggression became less of a tactical option for iwi, resulting in the end of total warfare. Battles were no longer one-sided slaughters, and the futility of continued warfare became more evident to the chiefs and warriors of Aotearoa.

Fatigue was also a factor in ending the conflicts. After decades of almost continual raiding, Aotearoa’s iwi were exhausted. Many thousands of people had been lost in battle and countless others had been displaced from their ancestral lands, with some iwi no longer living in their tribal territory.

Many leaders at the time were coming to the same conclusion that the status quo could not last, and started to attempt reconciliation with their traditional enemies. In some cases, warring iwi negotiated peace agreements with each other with the assistance of neutral parties, and it was mutually agreed to cease the ongoing cycle of utu. The realization of the futility and total loss that war was beginning to sink in on both sides of the various feuds.

Christian missionaries also had more influence in the second half of the 1830s, and were another reason for the end of the wars. Missionaries frequently encouraged peaceful relationships between iwi and the settlement of disputes through peaceful means, especially after many important chiefs had converted. Missionaries acted as intermediaries between different iwi, and their presence during negotiations and discussions allowed for truces between some traditional enemies. They also provided an alternative basis of law and morality in which the old cycle of revenge could be replaced, though this was not always successful or agreed to.

The arrival of the first British ship bearing the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 was seen by many Māori as a symbol of the increasing dominance and influence of the colonial government. By the time the Treaty of Waitangi was signed, some Māori were interested in maintaining a measure of protection by the Crown against settler incursions and external influences. In contrast, others saw it as a cession of power to the British government. The British now had a foothold to begin to control not just settlers, but also Māori. As the apparatus of government and colonial society was set up, intertribal warfare became less common and instead would be handled through negotiation and politics.

Although muskets continued to be used in conflicts throughout the 19th century, the wars that had been fought between the early 1800s and the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 had significantly changed the Māori world. The borders of iwi were changed, population levels had been shifted, and society pushed to its breaking point. The Musket Wars ended due to a lack of will to continue the conflict, rather than by a definitive end. In the period after the signing of the treaty, Māori were to face the struggles and issues of the colonial world.

Legacy and Transformation

The Musket Wars profoundly and indelibly changed Aotearoa and its people. The political landscape was significantly altered as the territorial boundaries of many iwi shifted. Some tribes expanded their territories through conquest, while others were driven into exile or subsumed by more dominant groups. Traditional alliances were disrupted, and new relationships were formed as tribes navigated the realities of musket warfare. The wars reshaped the political map of Māori society in ways that would have long-lasting consequences.

The demographic impact of the Musket Wars was severe. While estimates of the death toll vary, it is believed that tens of thousands of Māori were killed during the conflicts. Additionally, many others were enslaved or displaced from their lands. Entire regions were depopulated, leading to long-term shifts in settlement patterns. Communities that had once thrived in fertile valleys or along trade routes were scattered, and ancestral lands were left behind. The upheaval caused by the wars not only changed population distribution but also disrupted cultural continuity, as traditions tied to specific places were lost or forgotten.

Culturally, the Musket Wars had a lasting impact. The design of fortified pā (hilltop strongholds) was modified to better withstand firearms, reflecting both adaptation and resilience. Oral histories and waiata (songs) from the period memorialized the losses, survival, and acts of vengeance that occurred, embedding the Musket Wars deeply into the collective identity of Māori. The wars also influenced how Māori iwi interacted with European settlers, as the experiences of conflict and adaptation fostered both caution and pragmatism in the face of new threats. The scars left by the wars were still fresh when Māori later had to confront colonial expansion.

In a way, the Musket Wars paved the way for the colonial New Zealand Wars of the mid-19th century. By the time conflicts with the Crown over land and sovereignty began, the earlier conflicts had weakened many iwi. Their numbers had been reduced, and their traditional alliances had been fractured. This put Māori at a disadvantage when they were forced to confront new challenges posed by colonial expansion. In this sense, the Musket Wars indirectly smoothed the path for colonial dominance, leaving Māori more vulnerable to European encroachment.

The Musket Wars are a defining chapter in New Zealand’s history. They mark a turning point, the transition from traditional intertribal rivalries to a new era defined by European contact and colonization. The resilience of Māori in the face of the upheaval and challenges brought by the Musket Wars underscores their ability to adapt, rebuild, and endure despite immense odds. Remembering this period is crucial to understanding how Aotearoa and its people were transformed, for better or worse. It is a testament to the fact that societies are often forged in the crucible of hardship, and the Musket Wars were central in shaping the society that would later confront the pressures of colonial rule.

Conclusion

The Musket Wars had a profound and lasting impact on Aotearoa. The conflicts resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, the displacement of iwi, and the abandonment of ancestral lands. Despite the devastation, Māori society demonstrated remarkable adaptability. New forms of warfare emerged, alliances were formed and broken, and traditions were adapted to meet the demands of the rapidly changing world. The Musket Wars reshaped the territorial and political landscape, leaving a legacy of both tragedy and transformation.

The legacy of the Musket Wars continues to be felt in New Zealand today. The conflicts set the stage for the colonial struggles that would follow and underscored the resilience and strength of Māori communities. Remembered as a time of immense suffering, the Musket Wars also highlight the enduring ability of Māori to rebuild and maintain identity in the face of significant adversity. Their legacy remains an integral part of the cultural and political story of New Zealand.