The Price of Addiction: The Opium War’s Lasting Consequences

The Opium Wars of the 19th century represented a critical juncture in Chinese history, signaling the beginning of an era of foreign domination and national humiliation. The conflict began in the early 1800s, when Britain, in search of new markets, started exporting opium to China in massive quantities. The addictive nature of the drug led to widespread addiction among the Chinese population and a significant outflow of silver from the Chinese empire to pay for the opium.

In an effort to curb this trade, the Qing dynasty took action by seizing and destroying a large opium shipment, which incited the British to respond militarily. This led to two significant wars, the First Opium War (1839–1842) and the Second Opium War (1856–1860).

The impact of the Opium Wars on China was profound and far-reaching. The imposition of unequal treaties marked the beginning of a period of semi-colonial status for China, during which foreign powers exerted significant control over the country’s trade and resources. This not only weakened China’s economy but also its political stability, as the Qing government was seen as weak and incapable of defending the nation’s interests.

The Rise of the Opium Trade

By the end of the 18th century, Britain’s demand for Chinese products, such as tea, silk, and porcelain, had grown enormously. However, China’s restrictive trade policies, which limited foreign trade to the port of Canton and required payment in silver, led to a severe trade imbalance, draining Britain’s silver reserves. To address this, Britain turned to a highly profitable and destructive commodity: opium. Cultivated in British-controlled India and smuggled into China, opium became a potent economic weapon, reversing the trade deficit and filling British pockets while wreaking havoc on Chinese society.

The British East India Company was instrumental in the expansion of the opium trade. Officially banned from directly selling opium in China, the company cultivated the drug on a large scale in India and used private traders to sell it in China. This allowed Britain to distance itself from the trade while still profiting massively. By the early 19th century, tens of thousands of chests of opium were entering China annually, despite repeated prohibitions by the Qing government. Corrupt Chinese officials and merchants, seduced by the opium profits, looked the other way as addiction spread among all levels of Chinese society.

Opium addiction caused severe problems in China, devastating its economy and society. As addiction spread among farmers, laborers, and scholars, productivity plummeted, and the empire’s strength waned. China’s silver reserves, previously plentiful, began to flow out of the country to pay for opium, causing inflation and financial instability. Families were torn apart by addiction, leading to widespread misery and crime. The Qing government recognized the threat of opium and made several attempts to suppress the trade. Still, Britain’s economic interests ensured that the flood of opium into China would continue unabated.

The opium trade’s rise marked a turning point in China’s history. What had begun as a British economic measure to balance trade led to the widespread destruction of Chinese society and economy. The profits reaped by British merchants came at the cost of an empire in decline. The addiction crisis and China’s inability to control foreign exploitation set the stage for military conflict, humiliating treaties, and a prolonged period of national suffering that would shape the country’s future.

The First Opium War (1839–1842): China’s Defeat and the Treaty of Nanjing

In 1839, the Qing Dynasty launched its most aggressive attempt to end the opium trade. Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu seized and destroyed thousands of tons of opium in Canton and banned foreign trade with the Chinese. Lin placed increased restrictions on foreign merchants, and expelled British traders who refused to stop selling opium.

The British were furious. The ban threatened to cripple their trade, which they had worked so hard to build up. It was a direct attack on Britain’s economic and political interests in Asia. Diplomatic negotiations broke down, and Britain sent a military expedition to China in response. The First Opium War had begun.

Armed with the latest steam-powered gunboats and artillery, the British Royal Navy had a decisive technological advantage over China’s outdated forces. The war started in November 1839 when the British blockaded the Pearl River, cutting off Canton’s trade. Chinese wooden junks and antiquated cannons could not withstand the firepower of the British ships. At the Battle of Chuenpi in January 1841, the British squadron destroyed the Chinese fleet. British soldiers then landed on Chinese soil, taking control of coastal forts and towns with little resistance.

The war continued in 1841 and 1842 as the British forces moved up the Chinese coast. In March 1841, the British captured the city of Canton after intense fighting. The Qing military was no match for the well-trained and well-equipped British soldiers. In December 1841, the British launched an amphibious assault on the port city of Amoy (Xiamen) and easily took control. In 1842, British forces advanced up the Yangtze River, capturing Shanghai and eventually Nanjing, forcing China to sue for peace.

The First Opium War officially ended with the Treaty of Nanjing in August 1842. In this humiliating agreement, China was forced to cede Hong Kong to the British and open five treaty ports—Shanghai, Xiamen, Ningbo, Fuzhou, and Canton—to British trade. China also had to pay a large indemnity for the destroyed opium and war costs. The treaty also gave British citizens in China extraterritorial rights, meaning they were exempt from Chinese law and subject to British law instead.

The Treaty of Nanjing was a catastrophic blow to China’s international prestige. For the first time, foreign powers had directly taken control of parts of the country, weakening it. It also showed that China’s military was no longer up to the West’s technological standards. The treaty marked the start of what became known as the “unequal treaties,” in which China was forced to cede more and more of its sovereignty to foreign powers over the next century.

The defeat also shattered the myth of Chinese invincibility and marked the beginning of a period of Western exploitation and humiliation. The First Opium War was a turning point in Chinese history and would shape its national identity for generations to come.

The Second Opium War (1856–1860): Further Humiliation

The Second Opium War (1856–1860) was initiated by Britain in 1856 when, with the pretext of a dispute over the seizure of a Chinese-registered ship called Arrow, it declared war on the Qing dynasty, which was still not fully recovered from the First Opium War. France soon joined the war on the pretext that a French missionary had been executed. With China still on the defensive, the two Western powers, this time joined by the United States, demanded an increase in trade, the legalization of opium, and even more concessions to foreign envoys that would further infringe upon Chinese sovereignty.

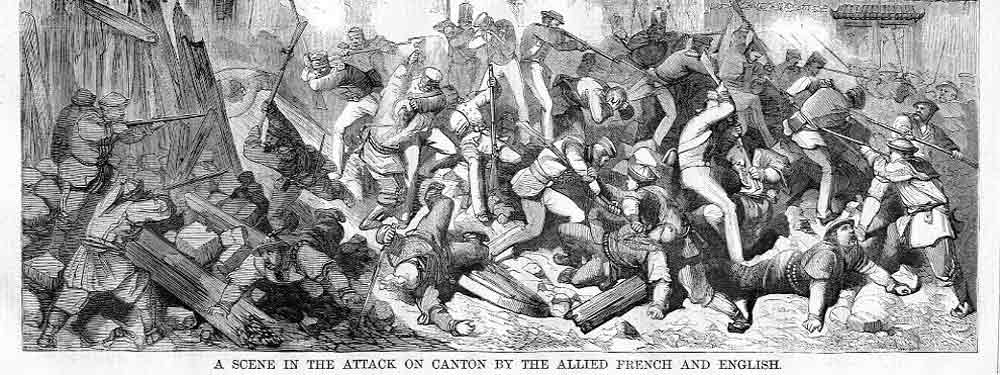

The war can be divided into two distinct phases. In the first phase of the war, British and French forces attacked Canton (Guangzhou) in 1857. After bombarding the city, they occupied it in early 1858, and then, encountering little resistance, marched north and occupied the Taku Forts outside Tianjin (Tientsin). The Qing government, aware that it was on the defensive, offered to negotiate. The resulting Treaty of Tientsin (1858) granted the foreign powers new privileges, including the legal importation of opium, new trading ports, and the right for foreign diplomats to reside in Beijing. The Qing court, however, was not interested in fully implementing the treaty, and a new phase of fighting broke out in 1859.

In the second phase of the war, China again sought to resist further foreign encroachments by strengthening the Taku Forts, but in June 1859, British and French naval forces were forced to retreat when their armies were rebuffed from entering the Peiho River. This failure was to be short-lived. In 1860, Britain and France responded with an all-out invasion. After storming the Taku Forts, Western forces proceeded to Beijing. The ill-equipped and demoralized Qing army could not halt the onslaught. In October 1860, British and French troops entered Beijing in a horrific culmination of the war.

One of the most notorious actions of the conflict was the destruction of the Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan), a massive imperial complex replete with cultural treasures of incalculable value. In retribution for the ill-treatment of European diplomats, British and French soldiers ransacked the site, looting various treasures and burning it to the ground. The sacking of this potent symbol of Chinese imperial glory deeply humiliated the Qing government. The destruction of Yuanmingyuan remains one of the most egregious scars on China’s national memory. The defeat underscored the Qing Dynasty’s impotence in the face of Western power and sowed the seeds of deep-seated resentment against foreign influence.

In the treaty settlement that concluded the war, known as the Convention of Peking of 1860, further foreign rights in China were extended. The Qing government was also forced to ratify the Treaty of Tientsin, legalizing the opium trade and opening further treaty ports to Britain and France. Russia, which had not been at war with China but had seized on the opportunity to press its territorial claims, also acquired Chinese territory through separate negotiations. The treaty was yet another severe erosion of Chinese sovereignty and a blow to Qing prestige.

The settlement enshrined extraterritoriality and greater Western rights to travel in the interior, as well as the right to station troops and open churches in the treaty ports. The Qing government, once the hegemonic power in East Asia, had become a puppet to foreign interests. The Second Opium War laid the groundwork for further Western and later Japanese encroachments.

The war reinforced a process that has come to be known as China’s “Century of Humiliation.” From the Opium Wars to the Boxer Rebellion and beyond, China faced a foreign-dominated world, domestic instability, economic depression, and the deep-seated perception that the Qing Dynasty could not protect its people or its country. The legalization of the opium trade and consumption only served to exacerbate domestic social ills further. The loss of tariff and territorial autonomy at a critical period of Western industrialization ensured China’s continued exploitation by foreign interests. The legacy of the Second Opium War would come to define China’s relationship with the world and drive later nationalist movements in their fight for modernization and independence.

The Era of Unequal Treaties and Western Domination

China’s defeat in the Opium Wars signaled the start of an era of submission to foreign powers. The Western powers, along with Russia and Japan, all took advantage of China’s military weakness to gain trade and territorial concessions. The treaties that China signed at this time granted Westerners special privileges and were known as “unequal treaties” because the Qing government had little choice but to sign them. The main points of the Treaty of Nanjing (1842) and the Treaty of Tientsin (1858) were confirmed in subsequent treaties over the next 60 years. China’s economic and legal sovereignty was further eroded, and foreigners gained a powerful presence in China’s major cities and on the country’s waterways.

A key provision of these treaties was the opening of treaty ports, Chinese cities where foreign governments, not the Chinese government, had control over trade, customs, and policing. Shanghai, Canton, and Tianjin were among the cities that were opened as treaty ports.

Foreigners were able to make these treaty ports into centers of their economic and military influence. Foreign companies could control China’s foreign trade, and the Chinese government was denied the right to try Westerners in Chinese courts. This legal concept, known as extraterritoriality, meant that foreigners accused of crimes in China were tried in their home countries’ consular courts rather than in Chinese courts.

Politically and economically, these treaties would tear China apart. It was now open season on the Chinese market, with foreign nations exerting control over tariffs and taxation. Domestic companies and industries were unable to compete against a flood of cheaper imports, while Chinese consumers grew accustomed to Western goods and services. Opium was now legal, which only added fuel to the fire of crisis. More Chinese people became addicts, further hurting the country’s workforce and economy, and creating yet another reason to hate Westerners.

The Qing government, already hard-pressed to maintain order, could not even fully control its own economy or citizens. The powerlessness of China at the hands of foreign powers was infuriating to government officials and citizens alike, as the once-great empire became an economic pawn of Western nations.

China was on its way to ruin, as the effects of addiction started to take their toll on the people. Corruption and powerlessness within the Qing Dynasty also led to greater internal chaos. The Qing Dynasty was seen as weak and ineffectual, with its inability to stand up to Western powers only making it even more unpopular with its own people.

After a series of rebellions and conflicts like the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), one of the bloodiest wars in history, Chinese revolutionaries attempted to topple the Qing Dynasty, which they saw as having lost the Mandate of Heaven. With Western powers taking over China and their own people rebelling, the Qing Dynasty was forced to appease the West while also fighting back against its own citizens. This civil unrest only hastened the Qing Dynasty’s decline.

Western powers continued to take control over China by establishing spheres of influence. Russia got the northern parts of China, France took over southern China and Indochina. While the United States, despite never militarily intervening, used the Open Door Policy to take advantage of Chinese markets, all the while claiming to advocate equal trade rights for all Western powers in China, and ensuring that China would remain a divided economic zone and political satellite, rather than a unified threat. With Western powers calling the shots, Chinese independence was all but an illusion.

The unequal treaties in China changed the country forever. China, once one of the most powerful and successful empires in the world, had been reduced to a semi-colonial puppet state by foreign powers, who imposed their own rules and economic demands. Resentment toward Western nations would come to drive much of Chinese nationalism in the 20th century. Chinese foreign policy and political ideology would be forged by this memory of national humiliation at the hands of foreign nations. The high cost of addiction was far more than anyone had ever bargained for, and China would be paying for it for generations to come.

The Long-Term Effects: China’s Century of Humiliation

The Opium Wars were the catalyst for the Century of Humiliation. China’s Century of Humiliation was a period of semi-colonial rule and economic subjugation, beginning with the Opium Wars and ending with the mid-twentieth-century reforms. The Opium Wars left China’s economy in ruins. The Qing government’s inability to control trade and the subsequent foreign trade invasion harmed the Chinese economy. The opium addiction had also drained China’s silver reserves and the unequal treaties left the Chinese economy with no tariff autonomy. As time passed and imperialism became more aggressive, both Western powers and Japan expanded their reach and influence on China. The result was the semi-colonization of China, with foreign powers controlling large areas of Chinese territory.

These humiliations contributed to growing Chinese resistance to foreign powers. The Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) led by Hong Xiuquan, attempted to overthrow the Qing Dynasty and establish a new state following a quasi-Christian ideology. Although not directly opposed to foreign rule, the rebellion was partly driven by dissatisfaction with the Qing government’s failure to resist Western powers. The resulting civil war was one of the deadliest in history, causing millions of Chinese deaths and further destabilizing the country.

The Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901) was an anti-foreigner, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising by Chinese nationalists decades later. The Boxers directly targeted Westerners and Christian missionaries in an effort to end foreign control of China. An alliance of foreign powers ultimately crushed the movement, but it reflected growing Chinese resentment and the Qing Dynasty’s inability to protect Chinese citizens.

China’s Opium Wars and the resulting foreign interventions contributed to the development of Chinese nationalism. As China struggled to modernize and reform in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Chinese people’s resentment of imperialist powers grew. Reformers such as Sun Yat-sen saw the Qing Dynasty’s failure to resist foreign powers as evidence that China’s government needed radical political reform. Sun eventually overthrew the Qing in 1911, and the desire to end China’s subjugation and national weakness was one of the movement’s driving forces. Anti-foreign sentiment also partly motivated the May Fourth Movement of 1919, a student-led protest movement against continued foreign concessions and a weak Chinese position in the world.

China’s feelings of humiliation also influenced the development of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The CCP gained support in part by positioning itself as the only force capable of restoring China’s dignity after Western and Japanese aggression. Mao Zedong and subsequent Communist leaders of China framed their struggle as one against foreign imperialism, as well as an internal corrupt elite. The CCP used China’s treatment at the hands of Westerners and Japanese as a justification for radical political and economic policies. The Century of Humiliation continues to play a role in the political rhetoric of modern China, with leaders evoking it to strengthen a sense of nationalism among Chinese people and reject foreign interference.

The Opium Wars also had long-term effects outside of Chinese nationalism. China’s industrialization was set back by decades of foreign incursions and political instability. While the West and other rising powers developed through industrialization and colonization, China did not. As a result, China remained far behind in global economic and technological development until the mid-20th century. The resentment of being dominated and the memory of humiliation and loss contributed to later Chinese leaders’ desire to develop China’s military and industrial capacity and become more self-sufficient. China’s dramatic economic growth in recent decades is in many ways a direct reversal of the country’s losses during the Opium Wars, and Chinese leaders still refer to them to reject foreign influence.

China’s Century of Humiliation, rooted in the Opium Wars, deeply affected China’s national character. The tremendous loss of life and cultural change resulting from the Opium Wars and the resulting foreign aggression instilled a strong sense of historical grievance in the Chinese people. This grievance has continued to shape China’s domestic and foreign policies, as well as its interactions with other powers. The Opium Wars may have ended in the 19th century, but they continue to influence China in the 21st century as it faces domestic and foreign issues. The Opium Wars’ importance in Chinese history extends beyond trade and territory to China’s national struggle to restore its sovereignty and pride.

The Lasting Price of the Opium Wars

The Opium Wars had long-lasting effects that contributed to China’s decline over the next century. The Qing Dynasty was significantly weakened by foreign intervention, economic drain, and internal rebellion. This made it difficult for China to defend itself against further Western and Japanese encroachments in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Unequal trade terms, loss of territory, and military defeats sapped national confidence and contributed to social unrest. The wars exposed the limits of Chinese military power and the harmful effects of imperialism on a country that had once considered itself the center of the civilized world.

The Opium Wars also continue to influence China today in subtle ways. The humiliation of defeat and foreign intervention are major themes in Chinese politics and nationalism. Modern Chinese leaders have frequently invoked the “Century of Humiliation” to justify policies aimed at restoring China to a position of strength and warding off foreign interference. The country’s drive to modernize and become an economic powerhouse in the 20th and 21st centuries can be seen, in part, as a direct reaction to the humiliation and losses of that period. The focus on self-sufficiency, military build-up, and assertive foreign policy can be seen as an effort to make China into a country that can never again be dominated or controlled by foreigners.

The Opium Wars also carry lessons about the high price of empire for both the colonized and the colonizers. Britain, which profited greatly from the opium trade and territorial expansion, was instrumental in China’s destabilization. Its imperial ambitions caused long-term resentment and upheaval in China. The Opium Wars thus have a long legacy of suffering, rebellion, and transformation in Chinese history and the broader global order. They stand as a warning about the disastrous costs of economic greed, imperial overreach, and the forcible creation of dependent economies. In remembering and studying these wars, we can learn from the past to understand the complexities of modern geopolitics and the long scars of history.