The Sicilian Vespers and the Bitter Legacy of Angevin Rule

On Easter Monday in 1282, the bells of Palermo began ringing for evening prayers. They were the signal for a small outbreak of violence, the consequences of which would dramatically change the course of Sicilian history. The clash between townspeople and French soldiers quickly developed into a full-scale rebellion known as the Sicilian Vespers. In a matter of weeks, the uprising spread to every corner of the island. Furious Sicilians killed thousands of French inhabitants of the island. The bells that had rung in praise became the summons to revolt and murder.

In the lead-up to the Sicilian Vespers, Sicilians had suffered for years under Angevin government, with heavy taxes and extortion by the royal court and corrupt officials, and abuses by foreign soldiers. In the build-up to 1282, these indignities finally swelled into a shared anger that could not be contained. The Sicilian Vespers put an end to Angevin rule in Sicily. But its consequences were broader, resulting in wars between kingdoms and in a legacy of foreign domination, divided sovereignty, and deep distrust of outside powers in the Mediterranean.

The Angevin Arrival in Sicily

The ascent of Charles of Anjou was made possible by the political interests of the Papacy. Faced with the formidable presence of the Hohenstaufen family in southern Italy, Pope Urban IV and his successor, Clement IV, sought a champion to help them bring about an end to Hohenstaufen rule over Sicily. That champion was to be the power-hungry younger brother of Louis IX of France. In 1266, Charles was at the head of an army in Italy with Papal backing, and the following year, he achieved a decisive victory over Manfred of Hohenstaufen at the Battle of Benevento and claimed the Sicilian throne for himself.

Charles did not linger long in Italy before taking further action. In the crucial Battle of Tagliacozzo in 1268, he routed the army of Conradin, the last of the Hohenstaufen heirs. By the end of the year, Angevin rule over Sicily and southern Italy was a fait accompli. With the Papal blessing, Charles built a centralized monarchy on French lines, and he was able to exercise absolute control over his new realm in both political and cultural spheres and in both civil and religious matters. A friend of his, and a later Papal legate in Sicily, remarked that Charles had power and control over all issues in the Kingdom of Sicily “almost beyond comparison.”

Charles did not linger long in Italy before taking further action. In the crucial Battle of Tagliacozzo in 1268, he routed the army of Conradin, the last of the Hohenstaufen heirs. By the end of the year, Angevin rule over Sicily and southern Italy was a fait accompli. With the Papal blessing, Charles built a centralized monarchy on French lines, and he was able to exercise absolute control over his new realm in both political and cultural spheres and in both civil and religious matters. A friend of his, and a later Papal legate in Sicily, remarked that Charles had power and control over all issues in the Kingdom of Sicily “almost beyond comparison.”

The behaviour of Angevin soldiers was another matter of discontent. The chronicles of the time record how Angevin troops harassed the local population, and how Angevin rule threatened traditional rights. The French were seen as arrogant, culturally foreign interlopers who lived off the backs of the local people. A chronicler writing towards the end of Charles’s reign wrote of the Sicilians being “oppressed by the rule of the foreigners and groaning with an indescribable sigh.” The cultural gulf between the rulers and the ruled seemed to grow wider with each passing year.

By the late 1270s, the popular mood in Sicily had soured significantly. What had once been seen as an opportunity for the Sicilians to be liberated from Hohenstaufen rule now seemed like a cynical betrayal, with the Angevins in many ways proving to be more hated and oppressive than the family they had replaced. What had been started with Papal promises of justice and stability had turned into open enmity. It was a hostility that would have to wait until the bells of Palermo rang in 1282, not to call the people to prayer, but to rebellion.

The Seeds of Discontent

The Sicilian Vespers emerged from years of Angevin governance that had become increasingly despotic. The harsh treatment of the populace and various abuses by French soldiers and Angevin officials created an undercurrent of resentment. Charles of Anjou was a ruler who expected absolute obedience from his subjects. His governance style involved heavy taxation and resource extraction from the island to support his military campaigns in Europe, which sapped the vitality of the Sicilian economy.

The frequent presence of French troops on the island also aggravated local sentiments, as these soldiers were known for their arrogant behavior, frequent exactions, and outright harassment of the civilian population. Chroniclers of the time noted that the soldiers’ conduct towards the locals was particularly intolerable, setting the stage for widespread animosity. This simmering discontent was palpable in every corner of the kingdom, from the bustling markets of Palermo to the small villages dotting the countryside. It was against this backdrop of daily grievances that the population of Sicily found itself ready for rebellion.

Social and cultural tensions exacerbated the growing unrest on the island. The Sicilian population, which was a diverse mix of Latin, Greek, and Arab influences, often found itself at odds with the rigid hierarchical structures imposed by the Angevin rulers. The French administrative class, mostly unfamiliar with and unsympathetic to local customs, saw the Sicilians as subjects to be governed, not partners in the running of the kingdom.

Native Sicilians were often excluded from positions of power and influence, which were reserved for the French and other foreigners, breeding a sense of humiliation and exclusion. This exclusion was particularly felt among the nobility, who were used to a certain level of autonomy and influence in local governance. The Angevin administration’s disregard for local tradition and autonomy not only alienated the Sicilian elite but also sharpened the islanders’ collective identity in contrast to their rulers. As the cultural divide widened, the Angevin government’s efforts to maintain control without meaningful integration into Sicilian society only fueled the flames of dissent.

The Sicilian population was also enraged by the corruption within Angevin governance. It was common knowledge that tax collectors enriched themselves at the expense of the populace while justice was often skewed to favor those with Angevin connections. For the average Sicilian, both the courts and the government had become emblems of injustice and exploitation. This perception was succinctly captured by a contemporary source that stated, “the island groaned beneath the burden of unjust judges.” The belief that corruption was both systemic and endorsed, if not directly ordered, by the crown contributed to the general atmosphere of injustice.

Religious and traditional sentiments also played a crucial role in the collective Sicilian psyche. The islanders’ identity was closely tied to their local traditions, festivities, and, of course, the church. The Angevins’ attempts to control and tax these aspects of Sicilian life, coupled with reports of sacrilege and religious interference by the French soldiers, inflamed public sentiment.

The ringing of bells for Vespers on Easter Monday was a call to prayer that resonated with deeper symbolic meaning: a reminder of the enduring power of faith and community in the face of foreign domination. In this way, the deeply felt religious and cultural traditions of Sicily provided a framework of resistance and identity that stood in stark contrast to the imposed Angevin rule.

The Sicilian Vespers

On Easter Monday, 30 March 1282, the streets of Palermo were crowded with worshippers. As the bells tolled for Vespers, many of the people of Palermo were in churches, praying. As they filed out into the city streets, a French soldier or sergeant was either seen assaulting or making lewd gestures towards a local woman by the Church of the Holy Spirit. The actions were too much for those in the crowd to bear, and a group of Sicilians nearby gathered and attacked him. A fight quickly ensued, which was the spark that would burn down the Angevin Kingdom of Sicily.

Soon, armed with weapons, the uprising against French troops and officials started with astonishing speed. Palermo had become an armed camp, where the people of the city slaughtered Angevin soldiers and officials. Neighbouring houses were searched and plundered, and Frenchmen were cut down in the streets. French officials and their families were hacked to pieces. The entire city was in uproar, and the slaughter raged for hours, as men and women called upon others to join in the mass-killing of Angevin officials and troops, and then to search out and slaughter every French person in the city.

The news of what had happened at Palermo rapidly spread across the island; within days, garrisons in towns and villages across the island were attacked by locals, and French settlers and their families were slaughtered. The chroniclers record that as many as 3,000 French men, women, and children were killed in the first six weeks of the uprising, as local populations rose in revolt and sought to root out the French presence from their towns and villages. The slaughter of French men, women, and children was a determined and bloody purge.

Witness accounts varied in their interpretation of what they had seen. To some chroniclers, it was a wanton and dastardly massacre of the innocent. To others, it was retribution, revenge for years of brutal occupation. Bartholomaeus of Neocastro, in his description of the events, managed to capture both the sudden and explosive nature of the events in Palermo. The revolt, he said, had been “the sudden fury of a people long burdened”. But the uprising was more than just its violence.

The strength of the anger at Angevin rule across all parts of the population was one of the defining aspects of the Sicilian Vespers. The population of Palermo had risen against their rulers, and every single voice in the city seemed to be calling for the French to be hunted down and destroyed.

By the summer of 1282, the Angevin position in Sicily had been destroyed. The survivors from the French garrisons and officials had fled, or had been executed, and the island was in open revolt. The smouldering spark had started a blaze that had engulfed the Angevin Kingdom of Sicily. But it would not stop at the borders of Sicily. The revolt in Palermo would drag three kingdoms into one of the most destructive and bitter conflicts of the medieval Mediterranean.

From Revolt to War

The revolt of 1282 quickly outgrew its insular nature and attracted the attention of Europe’s great powers. The Sicilians, with their French oppressors gone, understood that they could not resist Charles of Anjou’s will to retake his lost kingdom on their own. The islanders looked to Peter III of Aragon, who also had dynastic rights over Sicily through his wife, Constance, the daughter of Manfred of Hohenstaufen. Peter answered their call and, in the closing months of 1282, he landed in Sicily. The Aragonese king was received as a liberator by those who wished to have protection against the Angevins’ return.

The conflict that would soon ensue became known as the War of the Sicilian Vespers. It was a war that would last, in one form or another, for two decades, from 1282 until 1302. It would pit the Angevins and their Papal allies against the Aragonese, who asserted their rights over the island of Sicily. Fought on an ever-expanding Mediterranean stage, the forces of Spain, France, and Italy were both on land and at sea in a struggle for the control of the island, but also for its trade and influence.

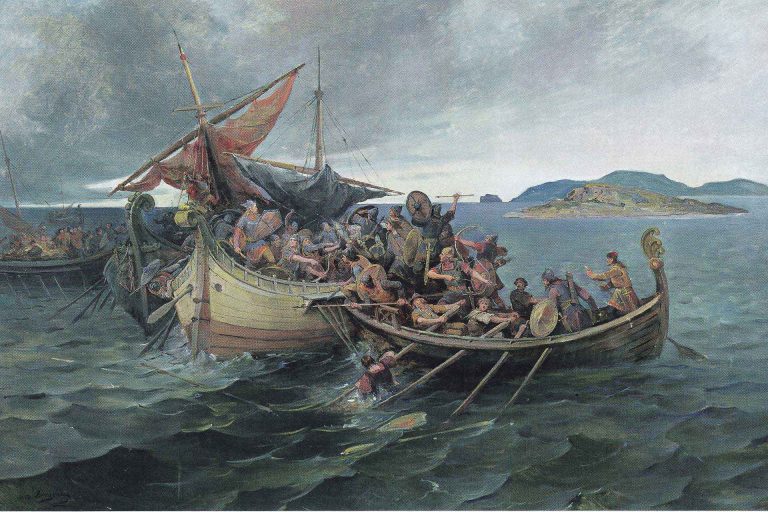

Sea battles were particularly influential, with the Aragonese naval fleet, led by the skilled admiral Roger of Lauria, inflicting heavy defeats on the Angevins and their allies. Aragonese dominance was only matched by the changing winds of war on land. The Papacy’s change in attitude against Peter III of Aragon led to Peter’s excommunication, and even crusades were called against Aragon. The island, under the protection of the Aragonese fleet and supported by the local population, remained resolute in its Aragonese leadership.

The kingdom itself was split, with Sicily falling under the Aragonese crown and the mainland territories – the Kingdom of Naples – staying in Angevin control. The division of the formerly united Kingdom of Sicily into two parts would last for centuries and shape the politics of southern Italy. The Mediterranean itself was now split between two rival courts, each claiming legitimacy and staking its own claim.

In 1302, the war came to a close with the Peace of Caltabellotta. The treaty ratified Aragonese sovereignty over the island of Sicily, while the Angevins remained in control of Naples. The legacy of the War of the Sicilian Vespers, the rivalry that it built, and the divisions that it sowed would last well beyond its official conclusion. What had started with the ringing of bells in Palermo would go on to become a decades-long struggle over the control of Sicily, and as such would change the balance of power in Europe and beyond, and the very nature of Italian and Mediterranean politics.

The Bitter Legacy of Angevin Rule

However, Angevin rule did not end with the uprising of 1282 or the War of the Sicilian Vespers. Despite these efforts, the upheaval did not lead to a more united or peaceful southern Italy. Instead, the revolt and subsequent conflict resulted in a fragmented kingdom and a bitter legacy. The former Kingdom of Sicily was now divided: the island of Sicily passed to the Aragonese, while the continental territories in peninsular Italy remained Angevin as the Kingdom of Naples. This geographical partition became a permanent political reality, with two competing courts and claims that would shape Italian politics for generations.

This division also solidified the reality of foreign control over the region. While Sicily was no longer Angevin, it was now ruled by the crown of Aragon, and Naples continued to be governed by a French dynasty. This reduced the autonomy of local governance, with power concentrated in the hands of distant rulers who often saw the territories as a means to their own ends. For many Sicilians, the change in overlords did little to address the underlying issue of foreign interference in local affairs.

At the same time, the legacy of Angevin rule left a bitter taste in the mouths of many Sicilians. The heavy taxation, imposition of foreign officials, and abuses of French soldiers under Charles of Anjou became emblematic of foreign oppression. The events of 1282 were both a moment of liberation and a warning about the dangers of outside domination. Chroniclers and popular memory painted the uprising as the just wrath of a people pushed to their limits, fostering a cultural suspicion of outsiders who sought to control the island.

The memory of the Sicilian Vespers would become increasingly potent in the years and decades following the conflict. The ringing of the vespers, the evening bells in Palermo on Easter Monday, came to symbolize the moment when Sicilians took their fate into their own hands, however briefly, and stood up to foreign domination. The revolt would be remembered as much for its assertion of dignity in the face of overwhelming power as for its violence. As later tradition put it, “the bells of Palermo called not only to prayer, but to freedom.”

This legacy would go on to define Sicilian identity for centuries. The political reality of foreign crowns over Sicily was a constant reminder of the island’s lack of autonomy. At the same time, the memory of the Sicilian Vespers served as a reminder of the Sicilians’ capacity for resistance. The Angevin period, remembered for its exploitation and arrogance, left behind a legacy of bitterness. At the same time, it gave birth to a story of defiance that would become a foundational element of Sicilian cultural memory, where resistance itself was a form of survival to be celebrated.

Recap of the Sicilian Vespers

The Sicilian Vespers was far more than a sudden outburst of violence; it marked the collapse of Angevin legitimacy on the island. The revolt demonstrated how years of resentment, exploitation, and foreign dominance could explode into a sweeping rebellion that transformed the political landscape. What began in Palermo on Easter Monday reverberated across the Mediterranean, ending French control in Sicily and shattering the illusion of Angevin permanence.

The rebellion also reshaped Mediterranean power struggles for decades to come. By drawing in Aragon, France, and the Papacy, the Sicilian Vespers escalated into an international war that divided the Kingdom of Sicily and altered the balance of naval and political power. The outcome cemented Sicily’s role as both a prize and a battleground in the struggle for dominance across southern Europe.