The Vietnam War: A War of Guerrilla Warfare and Global Politics

The Vietnam War raged from 1955 to 1975. It escalated from a civil war into one of the twentieth century’s most polarizing conflicts. After communist North Vietnam fought against French colonial forces between 1946 and 1954, tensions rose with noncommunist South Vietnam. But what started as a regional affair didn’t stay that way for long. American military personnel flooded into South Vietnam after 1965, and by the war’s conclusion, countless would perish. Vietnamese casualties were significantly higher. When Saigon fell in April of 1975, Vietnam was unified under communist control.

But Vietnam was more than just soldiers marching against each other. It was fought in rice fields and jungles, guerrilla ambushes and massive aerial bombardments. Hidden tunnel complexes allowed Việt Cộng fighters to move unseen, as Washington, Moscow, and Beijing turned Vietnam into a proxy theater of the Cold War. “We will not be defeated,” declared President Lyndon B. Johnson. Vietnam was won and lost just as much in grand strategy as it was in jungle warfare and insurgency.

Colonial Roots and the Road to War

The long Vietnamese struggle for independence began with French colonization. At the end of the nineteenth century, France tightened its control over Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia in a region that became known as French Indochina. The colonial government transformed Vietnam’s economy by building plantations and extracting raw materials. Many Vietnamese peasants were forced off their land or had to pay taxes. Nationalists began to mobilize in opposition to French rule. By the early 1900s Vietnamese independence activists combined traditional anti-colonial resentment with new ideologies like communism.

In 1940, Japan occupied Vietnam and replaced French colonial rulers. During World War II, Japan permitted French administrators to continue to govern Vietnam. When Japan surrendered in August 1945, Ho Chi Minh, a Vietnamese nationalist leader proclaimed himself leader of a new, independent Vietnam from Hanoi’s city hall. Echoing the American Declaration of Independence, he told listeners, “All men are created equal.” France quickly moved to regain control of Vietnam. Violence broke out across the country in 1946. France and its client State in Vietnam were at war.

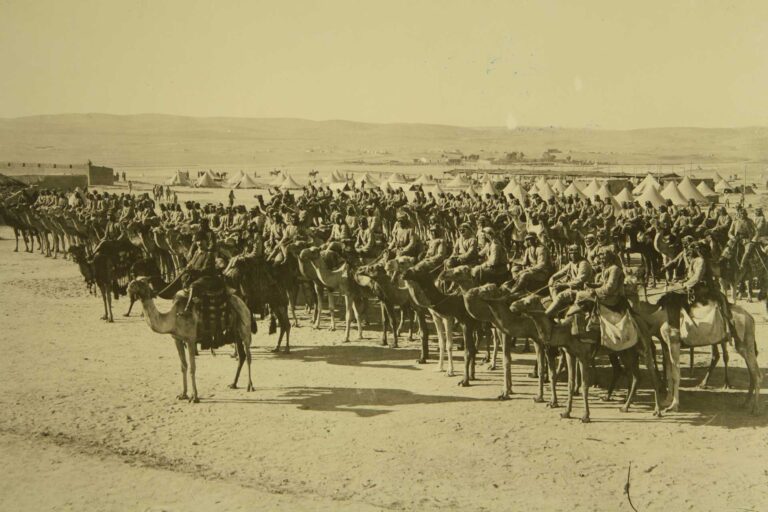

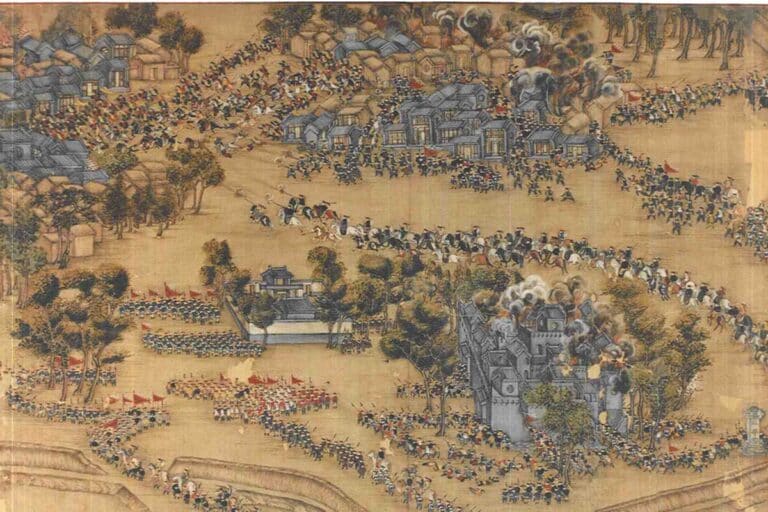

The First Indochina War was fought between French colonial forces and the Viet Minh, a communist-led nationalist movement. Under Ho Chi Minh and General Vo Nguyen Giap, Viet Minh fighters used guerrilla tactics and support from the local population to battle superior French forces. Clashes were often driven by the political leanings of the population, as well as by military action. As French forces attempted to control rural areas of Vietnam, they found themselves mired in a long guerrilla war. The war would last eight years.

General Giap spent most of the war harassing French forces in a war of attrition. French commanders believed that securing fortified bases in remote areas would provoke Viet Minh forces into an open battle. While the French built their base in a remote valley, Giap surrounded them with Viet Minh soldiers. Over several months he stockpiled artillery in the hills surrounding the valley. By May 1954, Giap’s forces were ready. French forces surrendered after an intense weeks-long artillery barrage. France had lost the battle.

9 October 1954. Waving to the city populace, joyous Viet Minh troops enjoy a parade of victory through the streets of Hanoi

France began negotiating for peace with Viet Minh representatives. World powers met in Geneva in 1954 to discuss the future of Indochina. The Geneva Conference would divide Vietnam until elections could be held to unify the country under a central government. Vietnam was divided at the 17th parallel, with Ho Chi Minh in charge of the north and a French client taking power in the south. Both sides agreed to hold national elections in 1956 to settle the matter permanently. Vietnam’s long war of resistance against French colonial rule had ended; however, the elections were never held, deepening mistrust.

Vietnam was now fully divided both politically and ideologically. Ho Chi Minh took power in North Vietnam and turned the region into a communist state backed by China and the Soviet Union. Fighting would continue between the nationalist government of South Vietnam and its neighbors to the north. Colonialism had set Vietnam up for a wider war.

The Cold War Context

After World War II, Vietnam had become a Cold War battleground between communist and anti-communist forces. The United States worried about the spread of communism throughout Asia. American diplomat George F. Kennan developed the policy of containment to prevent further communist gains. In Southeast Asia, colonial powers began to lose influence while several newly independent countries formed.

In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower defined the Domino Theory by publicly announcing his concerns that if one Southeast Asian nation fell to communism, then the surrounding countries would follow in succession “like a row of dominoes.” While Vietnam was relatively small and far away, the country’s fate seemed tied to the regional stability of Asia. Additionally, it was believed that if the United States appeared weak, it would lose prestige, and enemies would grow bold.

Eisenhower continued to supply South Vietnam with military aid and eventually deployed military advisors to help train its army, but drew the line at direct combat. When John F. Kennedy took office, he increased the number of military advisors in Vietnam and approved counterinsurgency programs. Kennedy would refer to the conflict as one step in the defense of freedom in the developing world.

Johnson became concerned with political instability in South Vietnam. In August of 1964, he gained congressional support with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. This allowed Johnson to increase the force in Vietnam as he saw fit. The number of American troops in Vietnam would increase dramatically over the next few years. “We seek no wider war,” Johnson would promise, but the United States was slowly drawn into combat.

North Vietnam had allies of their own. The Soviet Union agreed to supply weapons, training, and financial aid. The People’s Republic of China assisted with material and logistical support. While Moscow and Peking were competitors, they were both communists and wished to see Western influence defeated in Vietnam.

Vietnam became much more than a civil war between North and South. Political and military leaders from around the world had developed vested interests in the outcome of the war. Americans viewed their participation as a struggle for democracy while communist leaders promoted the idea of national liberation.

Guerrilla Warfare in the Jungle

The Vietnam War was largely fought in jungles, rice paddies, and rural villages. The lines of battle often disappeared into the dense jungle foliage. South Vietnam had communist guerrilla fighters called Viet Cong. They relied on ambush and evasion, and when possible, the Viet Cong avoided meeting the enemy head-on. Speed and surprise were essential to their tactics. This frustrated more conventional forces who were trained for conventional open warfare.

Ambush was a favored tactic of the Viet Cong. Small teams attacked patrols, convoys, and vulnerable outposts. The Viet Cong studied their enemy and exploited American patterns and schedules. Surprise booby traps such as punjabi spears, improvised explosives, and landmines were commonplace. These often primitive weapons required minimal equipment but inflicted severe injuries. Soldiers walked with caution because they never knew when they might step on a landmine or other trap. Morale suffered because troops couldn’t trust their surroundings.

Tunnels also added another dimension to the fighting. Extensive networks, such as the Cu Chi tunnels, ran underground. Hidden beneath the jungle and villages were supply caches, hospitals, and meeting areas. Soldiers could emerge from the jungle, disappear into a hole, and reappear miles away. Tunnel complexes were extremely difficult for American forces to locate. Fighting occurred both on the surface and underneath it.

Supply was another form of warfare. The Ho Chi Minh Trail was not one single trail but a series of truck and footpaths that cut through Laos and Cambodia. Supplies, food, and reinforcements flowed from North Vietnam to the south down these routes. No matter how many bombs were dropped, new trails appeared overnight. Trucks, bicycles, and manual porters transported weapons and food to troops below. It symbolized the tenacity and durability of the communist insurgency.

Combatants often blended in with the surrounding civilians. A lot of Viet Cong were Vietnamese locals who doubled as farmers and guerrilla soldiers. Sometimes it was impossible to distinguish between combatants and civilians. This blurred line between civilians and fighters led to further distrust. Many horrible atrocities were committed as a result of misplaced anger. The Vietnam War was as much a fight for the countryside as it was a military one.

Guerrilla warfare emphasized psychological stress on its enemy. Trying to outlast the enemy became more important than winning large-scale battles. “You have bigger guns,” Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap said. “But we have more time.” By remaining engaged and avoiding decisive conflict, they hoped to discourage political will in Washington.

The Viet Cong strategy was directly tied to the concept of a war of attrition. The United States wanted big body counts and kilometers cleared. The Viet Cong wanted to stay and keep fighting. Every attack and ambush had symbolic purposes. Even small victories could be used as propaganda. The longer the time went on, the more draining patrols became for American forces.

American Military Strategy and Escalation

American commanders began using their overwhelming conventional firepower as their involvement increased. Commanders expected enemy forces to collapse under the weight of superior weapons technology, mobility, and air support. Instead, combat often developed in unconventional ways. U.S. forces found themselves engaging small units rather than large enemy formations. Enemy combatants evaded large-scale military operations by hiding in the jungle.

By 1965, Rolling Thunder, a massive bombing campaign against North Vietnam, was initiated by the United States. Bombers ravaged the country from the air, destroying bridges, railways, trucks, and ammunition caches. American aircraft continued this strategy for years, but failed to weaken North Vietnam’s war effort. The North Vietnamese repaired bombed-out facilities and quickly substituted losses. The United States was unable to destroy enough of North Vietnam’s infrastructure to force it to surrender or come to terms.

Search-and-destroy missions became a large component of the conventional tactics used by United States Armed Forces personnel. Ground troops would fan out into an area, find the enemy, attack, then withdraw. Enemy body counts were used as a gauge of success. Victory was deemed possible by General William Westmoreland if enough communist troops could be killed. Small-unit engagements occurred often, but Viet Cong regulars were increasingly able to elude engagement by United States forces.

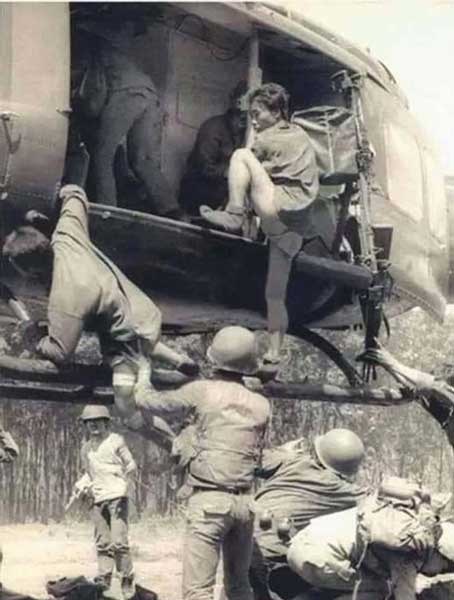

Helicopters were perhaps the most recognizable icon of the Vietnam conflict. Their ability to airlift troops quickly into hostile territory made them integral to America’s war effort. Casualties could be quickly evacuated from combat, allowing for relatively immediate medical attention. On the ground, dense jungle growth and camouflaged fighters limited visibility and maneuverability. Helicopter usage transformed the way the war was fought, but the Viet Cong would continue to elude capture.

Weapons like napalm were also used frequently. An incendiary chemical used to clear areas of jungle growth and enemy troops, its devastating power appalled those who saw its effects broadcast on the news. Air strikes on Vietnamese villages and civilian populations garnered worldwide criticism of how the U.S. was fighting the war.

Agent Orange was another chemical weapon used to clear dense jungle foliage. Chemical agents were sprayed from aircraft, destroying leaves on trees and many crops. The chemical remains in the soil to this day, causing adverse health effects to veterans who fought in Vietnam and to Vietnamese civilians. Agent Orange continues to affect people living in areas of Vietnam where it was sprayed.

The American escalation was born of the hope that increased force would yield quick results. But every new escalation highlighted the problems of prosecuting a determined foreign-supported insurgency. Superior firepower, technology, and mobility counted for much. But they did not easily translate into political or military victory. Escalation deepened and complicated the war.

The Tet Offensive and Turning Points

January 1968 saw a coordinated series of surprise attacks by communist forces across South Vietnam. The communist offensive occurred during Tet, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year. Over one hundred cities and towns fell victim to attack including Saigon, Hue, and even the U.S. Embassy compound in Saigon. The communist assault came as a complete surprise to American generals who had confidently spoken of success just months earlier.

In purely military terms, the United States and South Vietnamese counterattacks proved successful. Communist forces suffered tremendous casualties and were often removed from positions they overtook within weeks. Tet was by no means a decisive battlefield victory for North Vietnam. However, the intensity of the attacks stood in stark contrast to optimistic reports that the enemy was on the ropes.

As it turned out, the offensive’s political effects were far more significant than its military effects. Americans could not help but watch news footage of street fighting in Saigon and bombings in Hue. Suddenly, there was no denying the chaos. Support for official statements plummeted after the reality on the ground failed to match prior briefings that promised continual progress.

Journalist Walter Cronkite traveled to Vietnam to cover the Tet Offensive firsthand. Upon his return to the States, he famously described the war as being “mired in stalemate.” Cronkite was a respected news anchor who many Americans looked to for insight. Confidence in the war effort sank rapidly in the months after Tet. Protests became louder, and Congress and college campuses alike were left engaged in fierce debate.

President Lyndon B. Johnson would feel the pressure of these political effects. In March of 1968, he announced that he would not run for reelection. The Tet Offensive forever changed the political climate in Washington. The communists may have suffered greatly for their efforts on the battlefield, but succeeded in swinging the momentum of the war.

The War Beyond Vietnam

Fighting had started in Vietnam, but soon spread beyond Vietnam. Communist supply lines through roads and sanctuaries in Laos and Cambodia were viewed by Vietnam as essential for moving men and materiel south. American officials believed these supply lines should be stopped. Covert bombings began in Cambodia and Laos. These bombings would soon give way to ground operations.

Mission after mission bombed Laos using American aircraft. Disrupting communist supply lines was the main goal of these bombings. Most of these bombings were kept from the American public. Cambodia would see American and South Vietnamese troops enter their country starting in 1970. The Vietnam Conflict was spreading further, and regional instability was growing. Civilians would be impacted by the war yet again.

Anti-war protests were spreading throughout the United States. The more the United States became involved in the war, the more people knew about it. College students led protests on their campuses. “Make love, not war” signs were created and waved around. Citizens began burning their draft cards in public. War had returned to the United States.

Kent State University would become a hotbed of protest in May of 1970. National Guard soldiers fired into a crowd of protesters, killing four students. Outrage and disbelief spread across the country. A student protest had ended in tragedy, showing just how far-reaching the war had become. Support for government leaders continued to plummet.

Prominent voices began to speak out about the war. Vietnam veterans, priests, and even Martin Luther King Jr. were criticizing America’s involvement in Vietnam. Martin Luther King Jr. stated that the war was stealing resources that could be used for social betterment in the United States. King even called the war “an enemy of the poor” in one of his speeches. This associated the war in Vietnam with the inner cities of America. The conflict was transforming society in the United States.

Anti-war protests were happening across the globe, including in London, Berlin, and Tokyo. While the United States was trying to stop the spread of communism, protesters were encouraging it. Allies of the United States began to voice their disapproval of decisions made in Washington, D.C. Communist Governments around the world also spoke out against the United States. Tensions around the world began to escalate due to Vietnam, and trust in public officials continued to erode.

Even the peace talks were affected by outside sources. Vietnam and the United States were not the only ones meeting in Paris. The Soviet Union and China were also keeping a close eye on the peace talks. Vietnam was straining the United States relationships with Moscow and Beijing. Vietnam had become everyone’s problem.

Because of the spillover in Cambodia and Laos, as well as protests around the world, the Vietnam Conflict became an international crisis. Decisions about the war now had diplomatic consequences. Decisions about the war had to now take public opinion into account. Vietnam had spread beyond its borders and became a war that involved the whole world.

Vietnamization and Withdrawal

President Nixon wanted an “honorable end” to the Vietnam War, and when he took office in 1969, he promised to achieve it. Vietnamization was the policy of withdrawing American troops and installing enough support for South Vietnam to continue defending itself. The U.S. would slowly withdraw its troops while South Vietnam increased its military presence.

Vietnamization saw American troops leaving Vietnam over a number of years. The Army of the Republic of Vietnam received increased training from U.S personnel. Equipment and air support would be used to support the South Vietnamese effort. Troops would decrease over time, but bombing would continue in Southeast Asia. Nixon wanted to increase diplomatic pressure on North Vietnam while giving Americans at home a reprieve.

Negotiations for peace took place in Paris with diplomats from North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and the United States. Progress was slow, and both sides struggled to find common ground. Ceasefires, territory, and political futures were all argued over. In January 1973, after years of negotiation, the Paris Peace Accords were finally ratified by all sides. Both sides would cease military attacks, and remaining American troops would withdraw.

Combat troops withdrew from Vietnam, and American prisoners were freed and sent home. Fighting still took place between North and South Vietnamese troops. No political compromises had been reached, and the fighting simply resumed. The Vietnamization program had ended American participation in the conflict, but not the conflict itself.

American ground support was no longer there for South Vietnam. North Vietnam rebuilt its forces and began planning for a final assault. By early 1975, they had invaded and captured several southern cities. The defense of South Vietnam was growing weaker by the day. Observers from around the world watched and waited for something to give.

In April of 1975, North Vietnamese troops stormed into Saigon, the southern capital. Iconic images of evacuation from the U.S embassy would symbolize the end of America’s long war. Helicopters plucked helpless Americans from rooftops as throngs of South Vietnamese citizens looked on below. April 30th came and went, and South Vietnam was no more.

Vietnam had fallen under communist control after years of conflict. To Americans, it was a sickening feeling of failure. President Nixon resigned in 1974 amid an illegal campaign-finance scandal. In Vietnam, he had wanted to balance peace with honor, but it came at a cost. The controversial policy of Vietnamization withdrew America from the war, but could not end it.

Vietnamization allowed Americans to leave Vietnam, but not without cost. They were unable to broker a peace that kept South Vietnam intact as a nation and away from communist influence. The Paris Peace Accords slowed the war but did nothing to end it. Vietnam would end in battle, not through negotiations.

Human Cost and Moral Reckoning

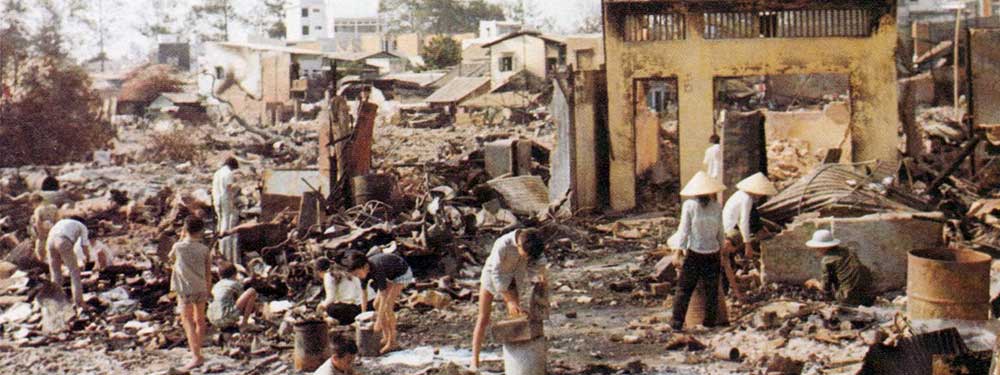

The Vietnam War resulted in the deaths of countless innocent Vietnamese civilians. Their homes were destroyed, their villages bombed and shot up, children orphaned, women raped, and men murdered. The war caused millions of Vietnamese people to become refugees as they tried to escape the bloodshed.

Hundreds of civilians were murdered by U.S. troops at My Lai Village in March of 1968. Most people in America did not learn about this massacre until investigative reporters broke the story. Army officer Hugh Thompson testified before Congress about stopping the massacre and risking his life to save the villagers. Reports of massacres and civilian casualties fueled the anti-war movement in the United States.

Vietnam War images featured bloody civilians, children covered in napalm burns, people who had lost their limbs, desecrated bodies of Vietnam Soldiers piled up like cordwood, and communities being destroyed from U.S. bombing raids. It didn’t matter how the generals spun it or convinced the public that we were winning the war. When people saw those kinds of images, it made them question the morality of what was going on in Vietnam.

Vietnam War casualties included over 58,000 U.S. service members who died and countless others who were injured. Many veterans who survived returned home with emotional and psychological scars. Many Vietnam Veterans even came home to hostility rather than a hero’s welcome.

There were many Americans listed as Prisoners of War or Missing in Action (POW/MIA). Families didn’t know what happened to their loved ones for years. Following the war, the U.S. government negotiated with Vietnam about POW/MIA issues. The uncertainty surrounding many of the missing military personnel left families dedicated long after the war was over.

After the war, many Vietnam Veterans had difficulties with social reintegration. As time passed, more research was conducted on what was then called Post-Vietnam Syndrome. We now know this as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Many Vietnam Veterans suffer from PTSD. Dreams, anxiety, substance abuse, and depression were common problems faced by veterans when they returned home from Vietnam.

In Vietnam, civilians were murdered, raped, and killed. Many became wounded or homeless from U.S. bombings. As communism took over, many people suffered from poverty and starvation. Rebuilding Southeast Asia took years, and for some families, the impact of the Vietnam War still hasn’t ended.

Legacy and Lessons of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War significantly impacted U.S. foreign policy. The executive branch became wary of using military force on a massive scale without clear goals or public backing. In 1973, Congress enacted the War Powers Act, restricting the president’s ability to send troops abroad without congressional consent. “Vietnam Syndrome” became a term used to describe America’s hesitation to engage in extended foreign conflicts. Vietnam taught policymakers that military might does not guarantee political victory.

The Vietnam War changed how leaders thought about insurgencies and counterinsurgency efforts. They analyzed guerrilla warfare and the importance of popular support paired with time and maneuverability. Subsequent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan looked to Vietnam for both examples of what to do and what not to do. The belief that hearts and minds matter became just as important as the 2terrain gained in battle. Leaders saw how superior technology failed to grind down an ideologically fueled movement supported by its people.

Vietnam also had international consequences. Russia and China’s support of North Vietnam created tension between the communist nations and the United States. It also led China and Russia to drift apart. On the other hand, the Vietnam War impacted foreign policy by leading to the United States’ partnership with China in the early 1970s. Vietnam proved that countries could change sides during the Cold War.

In Vietnam, the conflict eventually ended, and the country was reunified under communist control. The damage was eventually repaired, and Vietnam began to open its markets to foreign trade. The U.S. and Vietnam are now economic partners with diplomatic relations. This war proved that even conflicts that seem hyper-local can change the course of history.