The White Mouse: Nancy Wake’s Daring Role in Occupied France

Nancy Wake, nicknamed “The White Mouse” by the Gestapo, was one of the most wanted women in Nazi-occupied France. A former journalist, Wake was known for her crucial work with the French Resistance and became infamous among the Gestapo for her numerous escape routes. Renowned for being a tireless saboteur, Wake was a thorn in the side of the Nazis who were desperate to capture “The White Mouse”.

So relentless was her work that the Gestapo put a record price on her head as one of their most wanted women. The accomplished saboteur, who smuggled Allied pilots over the Pyrenees and led guerrilla fighters in acts of sabotage, is an outstanding heroine of World War II and a legendary spy.

Early Life and Background

Nancy Wake was born in New Zealand in 1912 but was raised in Australia. Her father left the family when she was a child, leaving her mother to bring up six children alone. Wake was an independent and resourceful child. By her teens, she was convinced that she would not be content with a conventional life in suburban Sydney.

At the age of 16, Wake ran away from home and became a nurse before saving enough money to travel. By the 1930s, Wake had made her way to Europe and had become a journalist. Wake trained in London, then became a correspondent in Paris. She was recognized as a witty and determined reporter. She travelled the continent, reporting for various newspapers.

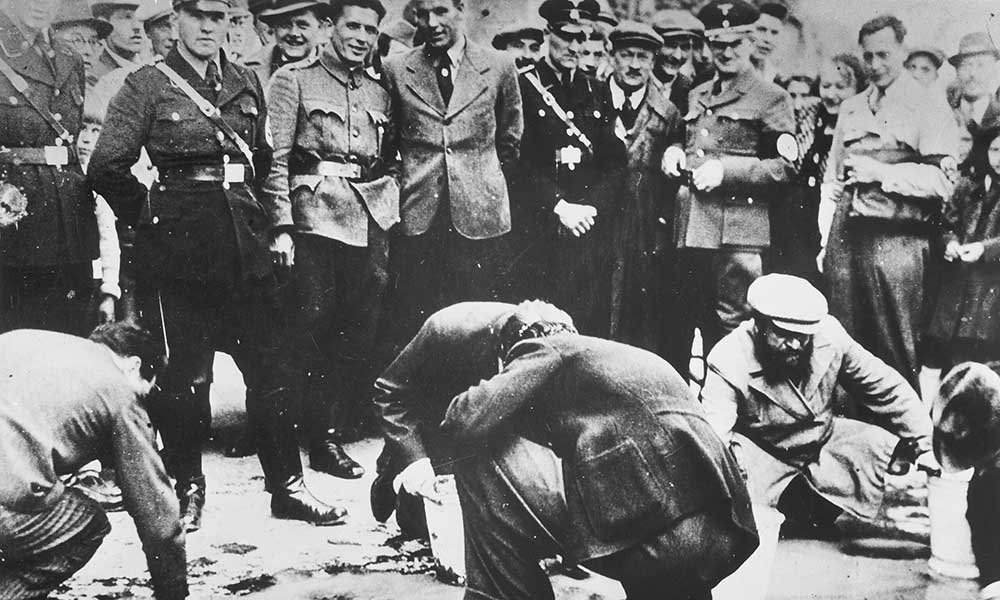

Nancy Wake observed a changing political climate on her travels through Germany and Austria. She watched Adolf Hitler rise to power, and fascism spread across the continent. She was also aware of the growing restrictions on Jews and political opponents. Wake later wrote in her memoirs that during her time in Austria, she was appalled by the mistreatment of Jews in Vienna. She claimed to have seen men in “long black coats with crooked hats” forced to wear chains on their feet, and dragged by the crowd into the streets to be whipped.

Wake developed characteristics that she would utilize during the war after these experiences: a hatred of fascism and strong independence. She said, “I had a personal dislike for Hitler from the moment I saw Jewish men chained to wheels and whipped in the streets of Vienna. From that moment on, I wanted to do my bit to see that the jackboot disappeared from Europe.” She was able to see the threat Hitler posed to Europe while many other leaders considered Hitler merely a boorish joke.

Wake was proud that she had moved across the world and been successful in a career as a journalist, but the start of the Second World War would see her reinvent herself once more. Wake had grown up with a sense of independence and a clear understanding of right and wrong. These personal characteristics would soon see her become one of the most formidable resistance fighters of the war.

Joining the French Resistance

Wake’s married life in France began in Marseille where she wed Henri Fiocca, a wealthy French industrialist, in 1939. The couple found happiness and comfort in their life together until World War II interrupted their plans. The Nazi invasion of France and the subsequent occupation of Paris pushed Wake out of the safety of her idyllic life. After all, her hatred for fascism, developed in the 1930s, was now given an opportunity for action. With the aid of her husband, Wake began her work as a member of the French Resistance.

Wake’s early work as a member of the Resistance began as a courier. She delivered messages and supplies to various groups, as well as information about the Nazi forces, an act that required bravery, guile and a sense of direction. These missions were challenging and highly dangerous, but few people in those days suspected that the petite young woman in haute couture was taking a life-and-death risk with every mission. She was an excellent communicator, and her career as a Resistance worker quickly expanded and intensified as her network of reliable contacts increased.

Part of Wake’s work as a courier was in helping to guide Allied soldiers and downed airmen across France and over the Pyrenees into Spain. Escape lines were in place for airmen shot down over occupied France, and Wake was one of the people who would help them on their way to Spain and eventually back into the fight. On each journey, Wake had to avoid German patrols, and her skill at fooling the Nazis in these high-stakes encounters endeared her to her fellow Resistance workers, to whom she later reported that she thoroughly enjoyed dodging the Germans, who never suspected a thing.

This work, of course, was fraught with danger. The Gestapo was on to an “anonymous woman” who was getting under their skin, if not yet to her identity. Wake’s work as a courier and smuggler of people would become the basis of an even more active and extremely dangerous involvement with the French Resistance.

The Gestapo’s “White Mouse”

Wake’s exploits within the Resistance only intensified as time went on. For the Gestapo, she was both a known thorn in their side and an enigma they couldn’t catch. Every other day, it seemed, German authorities would be sure they had her location, only for her to slip away once again. She would go on to be known by the nickname “The White Mouse” due to her knack for slipping through the Gestapo’s fingers. The name soon stuck and became one of the most notorious and well-known among the French Resistance.

Wake was at risk of arrest multiple times during her tenure as a courier and smuggler in France. However, many times she found herself lucky in avoiding capture. During one of these times, she found herself at a German checkpoint and luckily convinced the guards to let her pass. Another time, she was briefly arrested before her arrest was overturned, again by convincing the Germans she was just an innocent citizen. The more she slipped away, the larger the Gestapo’s myth of the White Mouse grew.

Her reputation increased among the Gestapo once they realized how vital a player Wake was for the Resistance. A mysterious woman who seemed to be able to accomplish any task was at the center of much of the intelligence they received. When they were able to officially confirm that the woman at the center of it all was Nancy Wake, they put her on their most wanted list, with a reported price of five million francs on her head. Wake, however, felt that the cost of her head was both a “distinction and a hazard.”

Nancy Wake’s more daring Resistance work only continued as the Gestapo seemed to set their sights on finding her. She later wrote, “the one pleasure I had was doing anything to annoy the Germans”. Every successful mission made her seem to be unreachable for the Gestapo, as the myth of the White Mouse only grew in power. By the early 1940s, Nancy Wake would no longer be just a courier or smuggler. She would also be a symbol, both loved by her fellow resistance members and hated by the Germans.

Training and Return with the SOE

By 1943, the situation for Wake in France was becoming so precarious that she was forced to escape. As the Gestapo was closing in on her, she made her way to Britain. There, she caught the attention of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), an organization formed by Winston Churchill with the mandate to “set Europe ablaze” with sabotage and espionage. Given her background and aptitude, they immediately recruited her.

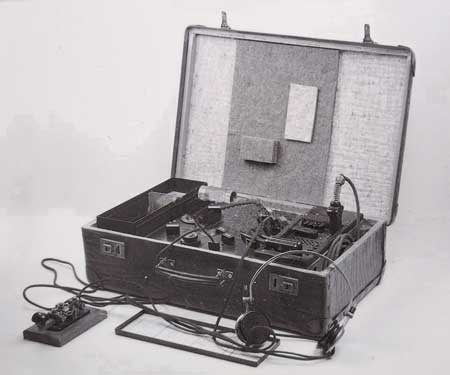

The training regimen at SOE was intense and designed to toughen agents for the realities of undercover work. Wake was taught the use of explosives, sabotage techniques, firearms proficiency, and fieldcraft under high-stress conditions. She also received training in wireless and cryptography, essential for communication with London. Her instructors noted her resilience and lack of fear, which distinguished her from many other candidates. Wake excelled in all aspects of the training.

Physical conditioning was also a significant part of her preparation. Wake endured parachute training, which she later described as both terrifying and exhilarating. Jumping from planes into enemy territory required a strong constitution and nerves of steel—qualities she had in spades. By the time she completed the course, she was both proficient in necessary skills and mentally and physically hardened for the mission.

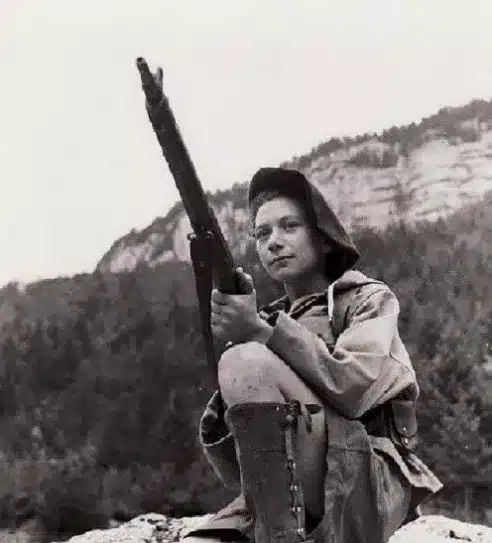

In April 1944, Wake parachuted into central France as part of a team of SOE agents. Their mission was to prepare the Resistance for the Allied invasion of Normandy. She was equipped with weapons, explosives, and wireless equipment. For Wake, returning to occupied France marked the beginning of her most perilous and daring period.

Wake’s return to France galvanized the Resistance efforts in her network. She orchestrated sabotage operations, targeted German supply lines, and prepared her groups for the imminent D-Day landings. Dropping into France was the culmination of all her training and experience, thrusting her back into the thick of the conflict she had joined years earlier. She herself said of parachuting back into France: “I felt as if I was coming home to finish the job.”

Resistance Operations in France

Returning to France with the SOE, Nancy Wake quickly became a vital conduit between London and the French Maquis fighters. She coordinated arms drops and organized supply chains. She was the critical link for delivering everything needed by the partisans to ambush German forces in the days leading up to D-Day. Wake proved not only adept at handling logistics but also excelled at boosting morale; as a result, she soon won the respect of even the toughest resistance fighters, who had initially been skeptical of female leadership.

Wake also took a direct role in guerrilla combat, planning ambushes, sabotaging railways, and disrupting communication lines. German convoys became common targets for the Maquis under her guidance. Their ability to disrupt the enemy’s troop movements and resupply operations significantly hampered German efforts. Her tactical acumen and decisiveness gave the partisans a real edge, and Wake thrived on the adrenaline of living dangerously on a near-constant basis.

Perhaps her most legendary act came when a critical set of radio codes was lost. Instead of risking the entire network, Wake set out on foot through occupied territory to deliver a new message to London. She evaded patrols and checkpoints, cycling more than 500 kilometers in just three days. The effort won her great admiration and remains one of the most celebrated anecdotes of her wartime activities.

A cold-blooded efficiency matched Wake’s personal valor. In one instance, she was cornered into hand-to-hand combat with a German sentry who had stumbled upon her position. To avoid putting her team at risk, Wake swiftly killed him with her bare hands—a grim but necessary act that demonstrated her resolve and unyielding nature.

Wake herself later acknowledged that war made for difficult choices. She could be charming and playful, but in the face of combat, she was unyielding. Resistance fighters and Allied officers who worked with her remembered her as fearless, pragmatic, and unforgiving. A leader who commanded respect and loyalty through her courage and effectiveness. By the time of the liberation of France, Nancy Wake had become a symbol not just of defiance but also of one of the most formidable and effective operatives in the fight against Nazi occupation.

Personal Sacrifices and Loss

Nancy Wake’s wartime years were not without personal tragedy and sacrifice, despite the heroics of her missions. Her husband, Henri Fiocca, a wealthy industrialist whom she had married before the war, was arrested by the Gestapo after Wake managed to escape to Britain. Despite torture and long months of interrogation, Henri would not reveal his wife’s activities to the Nazis. He was executed in 1943, and Wake was not made aware of his death until after the liberation.

Wake was never able to fully overcome the grief of losing her husband during the war. She had left France to continue the fight, planning to one day return and be with him. Instead, he was dead when she returned to Marseille, murdered not by the bullets of combat but by the Gestapo for keeping silent. Wake, in later interviews, said that she never forgave herself for his death, despite knowing that his silence was a final act of love and loyalty to his wife.

The emotional trauma of being on the run, always in danger, and participating in life-or-death missions did not just come from the loss of Henri. Wake often lived minute-to-minute on the edge of panic, her life hinging on a moment of wit or luck. Every mission was a dance with death and, in addition to facing her own mortality, she lost many friends and companions to arrest or execution. While she mostly hid her feelings behind a mask of quips and bravado, the emotional strain on her was immense.

The emotional trauma of being on the run, always in danger, and participating in life-or-death missions did not just come from the loss of Henri. Wake often lived minute-to-minute on the edge of panic, her life hinging on a moment of wit or luck. Every mission was a dance with death and, in addition to facing her own mortality, she lost many friends and companions to arrest or execution. While she mostly hid her feelings behind a mask of quips and bravado, the emotional strain on her was immense.

In a way, war stripped many people of more than their comforts. It stripped them of their identities, even their souls. To the world, Nancy Wake became “The White Mouse,” an elusive trickster and thorn in the side of the Gestapo. To herself, she was a grieving widow who managed to stay alive when so many others around her were killed. She carried both that public legend and her own private grief and loss through the war, and her ability to keep fighting in the face of her husband’s death was one of her most remarkable traits of those years.

Wake admitted in her later years that her involvement in the war and the resistance cost her her own happiness. She had done her part to help free France and to humble the Gestapo, but it had also cost her the life of the man she loved. The death of Henri Fiocca was a painful reminder that even the most extraordinary stories of war are often coupled with irredeemable loss.

Recognition and Legacy

Nancy Wake’s feats had not gone unnoticed. After the war, she received decorations from the grateful countries. In Britain, she was awarded the George Medal for bravery; in America, the Medal of Freedom; and in France, she received the Médaille de la Résistance and three Croix de Guerre, some of the nation’s highest military honors. Years later, she was appointed Companion of the Order of Australia, one of the country’s highest honors, to cement her place as one of the nation’s most extraordinary citizens. Wake received awards not just from one nation but from across the Allied world, testifying to the scope of her contribution.

Wake herself, however, was more likely to describe her actions as doing her duty. She was uncomfortable with being described as a heroine. In her own estimation, she had done only what needed to be done at the time. She was also fearless, highly effective at coordinating guerrilla forces and evasion of the Gestapo to the point where she became one of the war’s most effective operatives. Resistance fighters remembered her decisiveness, as well as the courage and humour with which she approached the challenges of the underground; characteristics that leavened her reputation for ruthlessness when engaging the enemy in combat.

Wake spent her final years between Australia, England, and Europe. She ran for public office in Australia but was unsuccessful, a sign that her wartime celebrity did not always translate to influence in peacetime. Wherever she lived, she remained a figurehead for the war, and her exploits would be retold to new generations.

Nancy Wake died in London in 2011 at the age of 98. As per her wishes, her ashes were scattered in a field near Montluçon, France, where she had fought with the Maquis in the forests. She was honored at her funeral with tributes from governments and veterans’ organizations from around the world. Newspapers referred to her as one of the most decorated women of World War II.

Wake’s story remains a powerful reminder that individuals are not helpless in the face of tyranny. The “White Mouse” showed that one determined woman could alter events in a war-torn continent. Her courage and sacrifice remain an example of resilience, fidelity, and the willingness to fight for liberty.

Nancy Wake – The White Mouse’s Enduring Legacy

From Nancy Wake, we learn of an unwavering spirit, a resilience of the heart that refuses to be extinguished even in the bleakest of times. Her story is a masterclass in the art of survival and the courage to resist oppression. Through her escapes, her leadership of the Maquis, she showed us that defiance can come in many forms: in a coded message, a sabotaged rail line, or a pistol held to a Nazi officer’s head.

She was a woman who refused to be cowed, a trailblazer who carved out a place for women in the narrative of warfare. Today, she is rightly remembered as one of the most decorated and formidable resistance fighters of the Second World War.

The White Mouse lives on as a symbol of resistance. Her life and deeds are now inextricably intertwined with the larger tapestry of the fight against tyranny. She stands as a testament to the power of the individual to make a difference, to change the course of history, and to be a beacon of freedom for generations to come.

![[Video] Fascinating World War 2 History Facts](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-11-at-7.17.46 PM.jpg)

![[VIDEO] How Fur Farms, World War II, and a Bomb Created Germany’s Raccoon Invasion](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Screenshot-2025-07-07-at-1.57.45 PM-768x512.jpg)

![[Video] The Battle for Castle Itter – “The Last Battle” of WWII](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-23-at-8.14.46 PM-768x480.jpg)