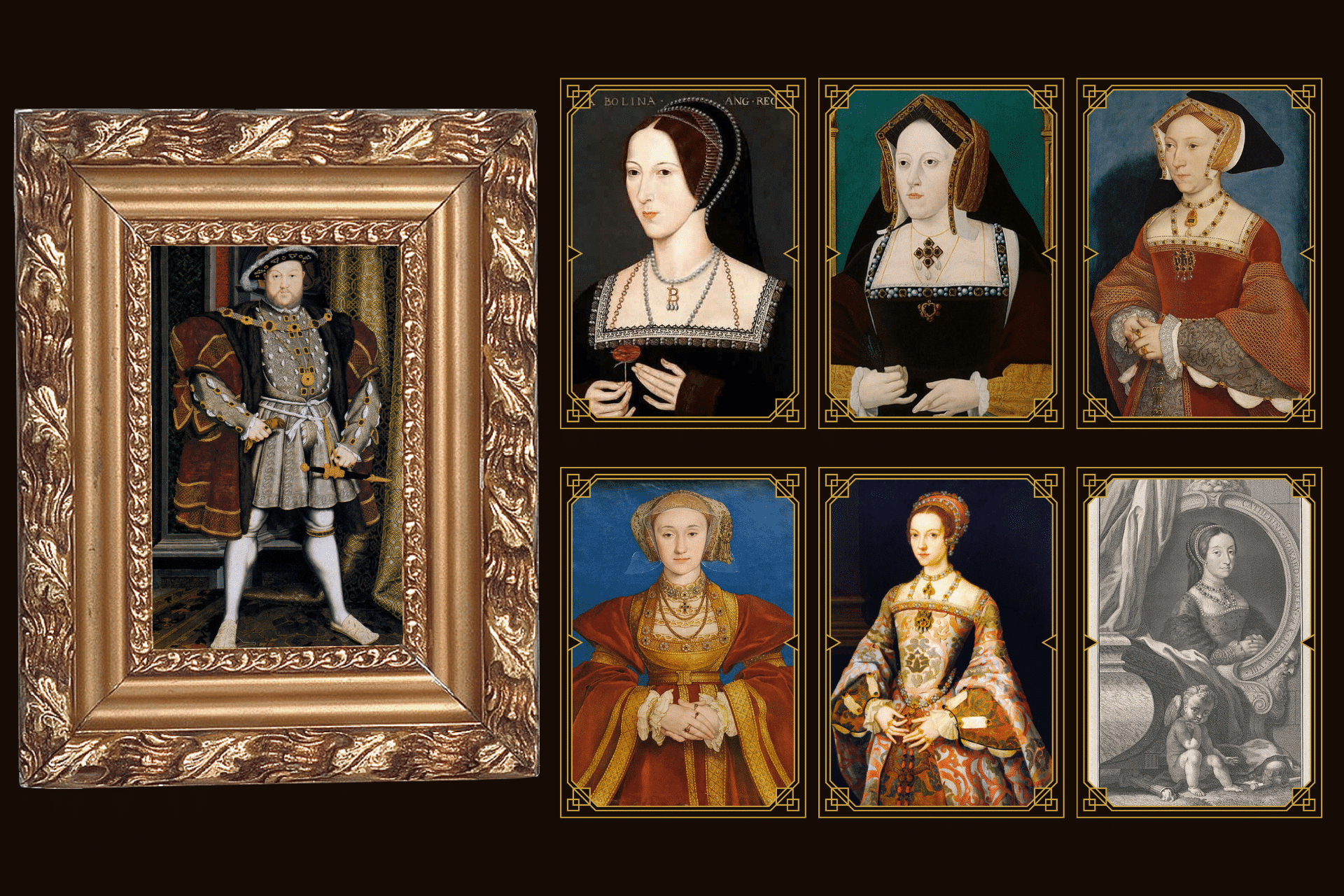

The Wives of Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England is well known for his six wives as well as his extensive religious reformation. His search for a son and his unquenchable thirst for power changed England’s monarchy and church. His six wives play a significant role in this epic story. Loved. Rejected. Executed. Henry’s wives were mistresses of the Tudor court, some tragic and others heroic. Their lives unfold into a tale filled with political intrigue, betrayal, love, and passion.

Catherine of Aragon

Married: 1509–1533

How the Marriage Ended: Annulled by Henry VIII after 24 years of marriage

Catherine of Aragon was the daughter of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. Her marriage to Henry VIII in 1509 was a diplomatic victory, strengthening the alliance between England and Spain. Catherine had been married once before, to Henry’s older brother Arthur, but he died shortly after their wedding.

Henry and Catherine’s marriage required a papal dispensation because of the biblical injunction against marrying a brother’s widow. Catherine maintained, however, that her marriage to Arthur had never been consummated. Henry’s marriage to Catherine turned out to be a solid one on the whole. She was intelligent, pious, and a capable diplomat. She served as regent in Henry’s absence during a military campaign in France in 1513 and skillfully oversaw the English victory over the Scots at the Battle of Flodden. Henry never completely lost respect for Catherine, but her inability to bear him a son eventually became the focus of his discontent. In their marriage, Catherine gave birth to eight children, only one of whom survived infancy, Mary.

In the 1520s, Henry became more and more fixated on the need for a male heir. He began to question the validity of his marriage to Catherine, claiming that it was against God’s law to marry the widow of his brother. Catherine was immovable in the face of these charges, however. She steadfastly maintained the legitimacy of her marriage to Henry and their daughter, Mary’s, right to the throne. Her defiance earned her the love and admiration of the English people, but it enraged Henry.

Henry’s interest in Anne Boleyn and his desire for a male heir led him to petition the Pope for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. When the Pope refused, Henry initiated the English Reformation, severing ties with the Catholic Church and establishing the Church of England with himself at its head. In 1533, Henry officially declared his marriage to Catherine null and void and married Anne. Catherine was banished from court and forced to spend the remainder of her life at Kimbolton Castle. She continued to style herself as the rightful queen, however, to the end.

Catherine died in 1536, likely due to cancer. She is said to have died while writing a letter to Henry, and her final words were, “your most loyal and loving wife”. Catherine of Aragon remains an enduring figure in history, remembered for her dignity, resilience, and her quietly stalwart faith. Her daughter Mary would later ascend to the throne, and Catherine’s line would not be extinguished.

Anne Boleyn

Married: 1533–1536

How the Marriage Ended: Executed for treason, adultery, and incest

Anne Boleyn was the second wife of Henry VIII, who played a pivotal role in advancing the English Reformation under the Tudor king. Anne was a lady-in-waiting for Henry’s first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and a woman whom the king took a strong interest in.

Anne was well educated, more politically astute and ambitious, and more assertive than was typical of noblewomen at the time. Anne’s refusal to become Henry’s mistress and become just another of his many sexual conquests turned her into a force that the king could not ignore. After failing to convince the Pope to grant him an annulment from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, Henry VIII divorced from the Roman Catholic Church and established a new national church. The Church of England not only changed the course of English history but also European history as a whole. Anne was crowned as queen just months after their marriage in 1533.

Anne’s time as queen was a mixed bag from the beginning. Anne was a significant force in the push for religious reform, and reform-minded individuals surrounded her at court. Still, her overbearing nature did not endear her to her fellow courtiers. Henry had essentially put all of his chips on the marriage to Anne, for she was expected to produce a healthy male heir.

Elizabeth, the daughter of Anne and Henry, was their firstborn, and two other pregnancies soon ended in miscarriage or stillbirth. Anne’s star in court was dimming. Old allies turned against her, and Henry began spending more time with his new mistress. It was not long until Anne found her enemies at court moving against her.

In 1536, Anne was stripped of her power, and a series of trumped-up charges was brought against her. The charges, which were almost certainly without any merit or truth to them, were that Anne had multiple sexual partners (before and during her marriage to Henry) and even conspiring to murder the king himself. Anne was tried alongside several men (including her own brother, George Boleyn) and was convicted and executed for her “crimes” by sword at the Tower of London on May 19, 1536.

She faced her death with a grace and dignity that belied her situation and her fate, reportedly uttering “I die a faithful woman to the king.” Anne’s historical legacy would endure long after her death. Although she died in disgrace, her daughter, Elizabeth I, eventually became the most famous queen of all England, ensuring that Anne would not just be remembered as the queen who changed England, but also as the mother of England.

Jane Seymour

Married: 1536–1537

How the Marriage Ended: Died of postnatal complications

Jane Seymour became Henry VIII’s third wife only a few days after the execution of Anne Boleyn. A lady-in-waiting to both Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, Jane was the polar opposite of her predecessor’s tempestuous reputation. She was mild-tempered, pious, and obedient. Henry valued these qualities and saw Jane as an ideal candidate to restore the dignity of his troubled monarchy.

Jane’s lasting value to the Tudor dynasty was the delivery of a male heir in 1537. The birth of Edward VI made Henry “the happiest man in Christendom.” Jane had delivered the long-awaited son who would carry on the Tudor name. She had done what both Catherine and Anne could not, and for this reason, she would be Henry’s most beloved wife. The birth was celebrated with a sumptuous ceremony, and Jane’s ghost did not haunt Henry as Anne’s had.

Jane fell ill three days after Edward’s birth, most likely from puerperal fever, a common infection of the time. Despite her physicians’ best efforts, Jane died a mere twelve days after the birth.

The death of Jane Seymour on October 24, 1537, was a significant blow to Henry. He mourned her passing in a way he never did for any of his other wives and later asked to be buried next to her at St. George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle.

Jane’s short time as queen was both fruitful and comparatively drama-free. Jane gave Henry the male heir he so desperately wanted and stayed far out of the political games her predecessors had tangled in. Jane did not rule long enough to establish an influential presence at court or implement any significant policy changes. Her son Edward and her image as Henry’s “true wife” would remain long after she died, but it was the king’s adoration for Jane that preserved her memory in an idealized light.

Anne of Cleves

Married: January–July 1540

How the Marriage Ended: Annulled by mutual consent

Anne of Cleves was the fourth wife of Henry VIII. She was brought to England primarily for political reasons. Thomas Cromwell brokered the marriage in an effort to gain a strong alliance with the Protestant German states. Henry was willing to marry Anne after seeing a flattering portrait of her painted by Hans Holbein. When he first met her in England, however, he reportedly expressed his disappointment by stating that she was “nothing like” her portrait and that she was a “Flanders mare.” The alliance was made, but it was clear to everyone right from the start that there was no spark between the two.

Henry never consummated his marriage with Anne, and after six months, he quickly secured an annulment with her cooperation. Anne herself provided the perfect grounds, admitting she had not been a virgin when she married Henry and that he had never consummated the marriage.

In return, Anne was treated very handsomely. She was provided with a generous settlement (including an estate and pension), was given the title “King’s Beloved Sister,” and was allowed to live out her life in peace and security. She was neither a queen nor a disgraced ex-wife. Anne of Cleves was an example of how not to play the game at Henry VIII’s court.

Anne outlived all of Henry’s other wives. She died in 1557 quietly and comfortably. Although her life was in many ways unremarkable, this in itself was a notable achievement. In a game of thrones where few came out unscathed, Anne of Cleves managed to both keep her head and survive Henry VIII.

Catherine Howard

Married: 1540–1542

How the Marriage Ended: Executed for adultery

Catherine Howard was the fifth wife of Henry VIII and a cousin of Anne Boleyn. Catherine was only a teenager when she was chosen to marry the aging king. Described as a beautiful and flirtatious young girl, the Howard family thought it would be a good idea to gain the king’s interest and return to favor at court. Henry, nearly 50 and very ill, was smitten by her young energy and affection and referred to her as his “rose without a thorn.” Their marriage was a whirlwind, being held just a few weeks after his annulment from Anne of Cleves.

The young queen’s past was about to come back and haunt her. There was gossip about her flirtations and relationships from her time at court and even prior. Catherine had formed an attraction with a gentleman of the king’s chamber, Thomas Culpeper, and many at court were suspicious of their closeness. An investigation found that she had had an affair with Francis Dereham and was likely still seeing Culpeper after her marriage. The scandal at court was enormous, and Henry was beside himself with betrayal and dishonor.

Catherine was arrested and held at the Tower of London. This time, the charges were a lot more founded than when Anne Boleyn was executed. Catherine confessed to the relationships she had with Dereham and Culpeper, but she was determined to say that Dereham had taken advantage of her. This did not matter because Catherine had acted treasonably while queen, so on February 13, 1542, she was executed at Tower Green. Her last reported words were that she died “a queen, but not a wife.”

Catherine’s short life and execution made Henry more paranoid than ever. Her actions showed that anyone at court was susceptible to the king’s quick rise to power and favor and just as easily a fall into infamy and death. Like her cousin Anne, Catherine Howard’s story ended with an execution, adding another bloodied story to Henry’s marriage quests for loyalty and a male heir.

Catherine Parr

Married: 1543–1547

How the Marriage Ended: Survived Henry’s death

Catherine Parr was Henry VIII’s sixth and final wife. The widow of two previous marriages, she was considered significantly older and more experienced than her immediate predecessors. She had a strong interest in religion and was well educated, authoring devotional books and corresponding with leading Protestant thinkers. Parr married Henry in 1543 in a partnership more focused on companionship and caretaking than on romance. During their marriage, the aging and increasingly ill king became more irritable and prone to angry outbursts.

Catherine was largely successful in reconciling Henry to his daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, and helping to restore them to the line of succession. She also proved a stabilizing force at court, and even acted as regent while Henry was on campaign in France for a time. Although she was inclined to Protestantism, Parr tempered her reformist views to avoid alienating the conservative religious establishment. At one point, she narrowly avoided arrest for heresy by persuading Henry of her fealty and subservience to his will.

Her pragmatism and political acumen kept her alive in a position that had already claimed the lives of two of Henry’s previous queens. As he became increasingly frail and infirm, Catherine continued to manage his medical care and deal with his mood swings. After he died in 1547, she was not only the first of his wives to survive him, but did so with her status and reputation intact.

Catherine remarried Thomas Seymour, the brother of Jane Seymour, shortly after Henry died in a match that was considered more romantic than her first marriage. However, her last years were marred by a scandal in which Seymour attempted to seduce the teenage Princess Elizabeth. Catherine died of complications from childbirth in 1548.

Legacy of the Wives of Henry VIII

The wives of Henry VIII are a subject of fascination and study, not just as the spouses of a powerful monarch but as influential figures in their own right. Through marriage to Henry, each woman, queen, consort, or widow, played a unique role in the Tudor court and the larger narrative of English history.

The six wives of Henry VIII all played pivotal roles in the events and reforms that shaped Tudor England, encompassing political alliances, religious transformations, dramatic court life, and succession crises. They each had unique personalities, backgrounds, and stories of ascent and, for some, downfall. The wives of Henry VIII were not only central figures in the king’s life but also pivotal in the historical events of their time, and they continue to be subjects of extensive research, literature, and public interest.