What Is a Pyrrhic Victory? 10 Real-World Examples

A Pyrrhic victory is a win with such a high cost that it negates the benefits of victory. Named after King Pyrrhus of Epirus, whose army suffered irreplaceable losses in battle despite tactical victories, this term defines a triumph where the victor’s losses are greater than the achievements gained. The price paid for the win is so great that the entity that ultimately won ends up damaged and weaker than it was before the contest. In such cases, the term “victory” is a misnomer because it not only fails to bring about any noticeable or lasting gain but also actually reduces the chances of achieving them.

In real life, entire armies and even empires have risen and fallen in battles and wars that resulted in a Pyrrhic victory. As such, this concept is vital in both historical and military contexts, because combatants must have an advantage large enough to allow for meaningful conquest, rather than just a token victory. This list contains ten examples of Pyrrhic victories in the real world.

The Battle of Heraclea

280 BC

Epirus

Commander: Pyrrhus of Epirus

Strength: Approx. 25,000 (including 20 war elephants)

Casualties & Losses: Estimated 4,000–7,000

Roman Republic

Commander: Publius Valerius Laevinus

Strength: Approx. 30,000

Casualties & Losses: Estimated 7,000–15,000

The Battle of Heraclea was fought in 280 BC near the river Siris in southern Italy. It was the first significant confrontation between the Roman Republic and Pyrrhus of Epirus. Pyrrhus, a Greek king, had come to Italy with the ambition of expanding his power and had been called upon to assist the Greek city of Tarentum against Roman encroachment. Commanding a force of veterans and his renowned war elephants, Pyrrhus defeated the Roman army of Consul Laevinus in a style of warfare which was new and confusing to the Romans.

Pyrrhus won the battle but with heavy losses to his veteran forces, from which he was unable to recover as easily as the Romans were. The discipline and stubbornness of the Romans, even in defeat, showed Pyrrhus that further victories against Rome would come at a cost. Following this bloody victory, it is thought he said, “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined.” The tone for the expense of Pyrrhus’ Italian campaign had been set at Heraclea; it was a victory, but he had seen the strength of the Roman ability to recover, and the weakness of his own reserves. The term “Pyrrhic victory” would soon enter the lexicon.

The Battle of Asculum

279 BC

Epirus

Commander: Pyrrhus of Epirus

Strength: Approx. 40,000 (including elephants and Greek allies)

Casualties & Losses: Estimated 3,500–5,000

Roman Republic

Commander: Publius Decius Mus

Strength: Approx. 40,000

Casualties & Losses: Estimated 6,000–8,000

The Battle of Asculum was a military engagement between Pyrrhus, the ruler of the Greek state of Epirus, and the Roman Republic in 279 BC. Asculum was located in southern Italy, where Pyrrhus had come to aid the Greek cities against Roman expansion. Pyrrhus’ first encounter with the Romans at Heraclea had been a costly success. Now, the Epirote king commanded an army that included war elephants and a Greek-style phalanx. The Romans, led by Consul Publius Decius Mus, were also back with reinforcements and with the same determination.

The armies fought for two days, with neither side gaining the upper hand. Finally, Pyrrhus broke through the Roman lines and forced the legions to retreat. The battle was a tactical victory for Pyrrhus, but a strategic one for the Romans. Pyrrhus’ forces were much depleted, and while the Romans could easily replace their losses, the king could not so easily replace his elite troops or Greek allies. An old quote attributed to Pyrrhus is, “Another such victory and I am undone,” and has led to the modern phrase “Pyrrhic victory.”

Pyrrhus never recovered from the Battle of Asculum. Despite his two battlefield victories, he had not broken the Roman spirit or their determination, and he was unable to achieve his strategic objectives in Italy. The story of Pyrrhus and his overextension of resources serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of overreaching and the actual cost of victory.

Battle of Bunker Hill

June 17, 1775

British Empire

Commander: General William Howe

Strength: Approx. 2,200

Casualties & Losses: Over 1,000 (226 Killed – 828 Wounded)

Continental Forces

Commanders: Colonel William Prescott, General Israel Putnam

Strength: Approx. 1,500

Casualties & Losses: About 450 (Approx. 115 Killed – 305 Wounded – 30 Captured)

The Battle of Bunker Hill was an early conflict in the American Revolutionary War, technically won by the British. They did manage to dislodge colonial troops from their defensive positions on Breed’s Hill. However, the victory was a hollow one as the British suffered over 1,000 casualties, more than twice that of the American side. This battle was one of the bloodiest of the entire war and served as a harsh wake-up call to the British.

The Americans were forced to withdraw after running out of ammunition, but their stand would become a symbol of defiance and fortitude. It was said by a British officer that “a few more such victories would have ruined us.” British morale suffered as their casualty rate made it clear that this would not be an easy rebellion to put down.

Tactically, the battle was a British success, but the Americans had gained something far more valuable. Their spirited defense against the professional British army inspired colonists to rally behind the revolutionary cause. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that Bunker Hill was a Pyrrhic victory that ultimately crippled the victors more than the vanquished.

The Battle of Borodino

September 7, 1812

French Empire

Commander: Napoleon Bonaparte

Strength: Approx. 130,000

Casualties & Losses: 28,000–35,000 (Around 6,500 Killed – Tens of Thousands Wounded)

Russian Empire

Commander: General Mikhail Kutuzov

Strength: Approx. 120,000

Casualties & Losses: 38,000–45,000 (Including Over 15,000 Killed)

The Battle of Borodino was the bloodiest single-day action of the Napoleonic Wars, and a brutal prelude to the French occupation of Moscow. While the French victory was technically a French victory, the cost to the invaders was immense. Napoleon’s forces were incurring tens of thousands of casualties to defeat a reeling enemy. The Russian army was battered, but not destroyed.

Bonaparte was reluctant to commit his Imperial Guard, and this may have cost him the victory. His army marched into a denuded and burning Moscow, where no surrender was forthcoming. Bereft of supplies or shelter, the Grand Armée began its legendary retreat. Pursued by Russian forces and scorched-earth tactics, the fight for Moscow became a war of attrition.

In the years since, Borodino has come to be seen as a classic example of winning a battle while losing the war. Napoleon’s Pyrrhic victory drained his forces at a critical point in the conflict. As the historian Adam Zamoyski has put it, “Borodino broke the spell of French invincibility.” The road to Moscow ended in catastrophe, with just a fraction of the army ever returning to France.

Battle of Malplaquet

September 11, 1709

Grand Alliance (British, Dutch, Austrians)

Commanders: Duke of Marlborough, Prince Eugene of Savoy

Strength: Approx. 86,000

Casualties & Losses: 20,000–25,000

Kingdom of France

Commander: Marshal Villars

Strength: Approx. 75,000

Casualties & Losses: 11,000–12,000

The Battle of Malplaquet was a significant engagement during the War of the Spanish Succession, but it was one of the bloodiest 18th-century battles. The Allied forces, led by the Duke of Marlborough, compelled the French to abandon the battlefield, but it cost them dearly. The Allies had twice as many casualties as the French, and the Dutch lost heavily due to a frontal assault on the French center.

The high price of the victory led many to consider it a pyrrhic victory. The scale of the carnage shocked the European public, and support for the war effort waned, especially in Britain and the Dutch Republic. The Battle of Malplaquet was a pyrrhic victory that failed to change the strategic situation and undermined the war effort.

Marshal Villars was reported to have said to Louis XIV: “If God gives us the grace to lose such a battle again, Your Majesty may count on his enemies being destroyed.” The quip summed up the ironies of Malplaquet, as France could still emerge from the war in a stronger position after the tactical defeat.

The Battle of Guillemont. 3 -5 September 1916. Dead German soldiers scattered in the wreck of a machine gun post near Guillemont. The photograph shows the destruction which occurred when the defense had no deep shelter. – John Warwick Brooke, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle of the Somme

July 1 – November 18, 1916

British and French Empires

Commanders: General Douglas Haig, General Ferdinand Foch

Strength: Approx. 1.2 million

Casualties & Losses: Approx. 620,000 (420,000 British, 200,000 French)

German Empire

Commanders: General Fritz von Below, General Max von Gallwitz

Strength: Approx. 1.1 million

Casualties & Losses: Approx. 500,000

The Battle of the Somme, one of the most well-known and symbolic battles in the First World War, serves as a metaphor for the futility of trench warfare. Within the first day of battle, the British had over 57,000 casualties, the bloodiest day in British military history. After several months of combat, the Allies advanced only six miles, a small victory amid an overwhelming loss of human life.

The battle was a quintessential pyrrhic victory, as the Allies ground down the German opposition and achieved small territorial gains, while losing a tremendous number of lives on both sides. The attack on the Somme never broke German lines and had lingering effects far beyond the war.

Soldiers on both sides lived under artillery strikes, machine gun fire, and mud-filled trenches without any form of meaningful strategic advancement. As the war continued, the Somme became a symbol for the abhorrent brutality of World War I. British veteran Siegfried Sassoon wrote, “I died in Hell – They called it Passchendaele,” but could have easily written it as, “I died in Hell – They called it The Somme.”

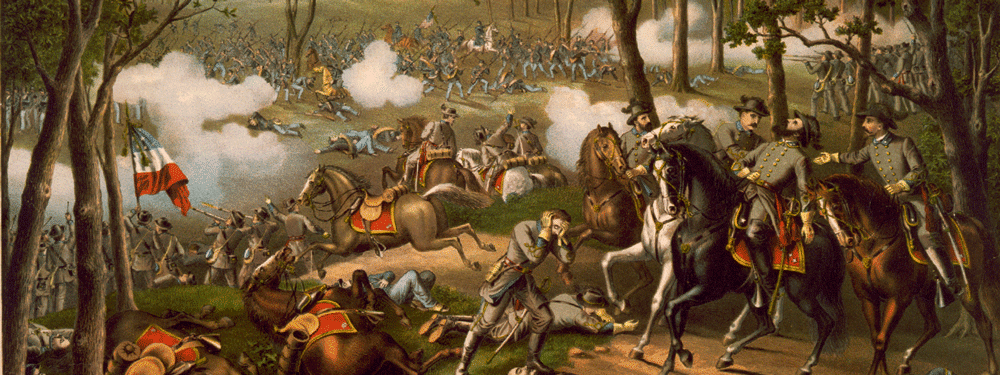

The Battle of Chancellorsville

April 30 – May 6, 1863

Confederate States of America

Commanders: General Robert E. Lee, General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson

Strength: Approx. 60,000

Casualties & Losses: Approx. 13,000

United States (Union)

Commanders: Major General Joseph Hooker

Strength: Approx. 130,000

Casualties & Losses: Approx. 17,000

Chancellorsville was arguably Lee’s greatest tactical triumph of the war. In a daring gamble, the outnumbered Lee divided his army. With the help of a surprise flank attack from General “Stonewall” Jackson, he turned the tables on Union soldiers and routed an army more than twice the size of his own. In the Eastern Theater, the tide had turned in favor of the South.

In a cruel twist of fate, Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men while on a reconnaissance mission, and he died of pneumonia weeks later from the infection of his wounds. His death was a monumental loss for the Confederacy. Although Lee won a great victory on the battlefield, Chancellorsville would be a Pyrrhic victory for the South as a whole, severely limiting its chances of ultimate success.

The General Confederacy mourned the loss of one of its greatest tacticians. The battle’s results had a tremendous impact on the psyche of both sides. The South had lost a general of Jackson’s caliber, one whom Lee never fully recovered from. Jackson’s leadership would be sorely missed in future campaigns such as the Gettysburg campaign. As the Confederacy declined, this battle showed the terrible price of victory.

The Battle of Okinawa

April 1 – June 22, 1945

United States

Commanders: Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, General Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr.

Strength: Approx. 183,000 troops

Casualties & Losses: Over 50,000 (12,500+ killed)

Empire of Japan

Commanders: General Mitsuru Ushijima

Strength: Approx. 77,000 troops

Casualties & Losses: Over 100,000 military deaths; tens of thousands of civilian casualties

The Battle of Okinawa was the last major amphibious assault in the Pacific Theater of World War II and among the bloodiest. The Americans invaded Okinawa to use it as a staging area for a potential invasion of mainland Japan. This led to nearly three months of fighting against a determined Japanese defense that dug in all the way down to the caves. The battle was uniquely horrific, as kamikaze attacks, cave fighting, and civilian suicides all added to the overall slaughter.

The United States would win and capture the island, but at a high cost. Over 50,000 Americans and hundreds of thousands of Japanese soldiers and civilians were casualties of the battle. For the United States, this battle was a pyrrhic victory. The suffering was so great on Okinawa that it helped dissuade U.S. leadership from planning a land invasion of Japan. This was one of the factors that led to the use of the atomic bombs.

Okinawa was both the beginning and the end. The general in charge, Buckner, was the highest-ranking American officer killed in action during the entire war. He was killed during the final stages of the battle. The U.S. had won a great victory, but it came at an unfathomable cost.

The Battle of Cannae

August 2, 216 BC

Carthaginian Forces

Commander: Hannibal Barca

Strength: Approx. 50,000 troops

Casualties & Losses: Estimated 5,700

Roman Republic

Commanders: Consuls Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro

Strength: Approx. 80,000–86,000 troops

Casualties & Losses: Over 50,000–70,000 killed, 10,000 captured

The Battle of Cannae is widely regarded as one of the most tactically brilliant victories in history. Facing a numerically superior Roman army, Hannibal used a double envelopment tactic to surround and destroy his enemy. The Romans suffered an enormous loss of life, with entire legions being wiped out in a single day. The ancient historian Livy described it as a “disaster unprecedented and unparalleled”, and the psychological impact on Rome was profound.

However, Cannae was ultimately a pyrrhic victory for Hannibal. He was too weak and too far from Carthage to march on Rome itself, and without reinforcements he was unable to deliver the final knockout blow. Rome would eventually recover, rebuild its army, and adapt its tactics, culminating in a final victory over Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC.

The Battle of Cannae serves as a potent reminder that even the most stunning tactical victory can become a strategic defeat if it is not accompanied by political and military follow-through. In a sense, Cannae can be seen as a pyrrhic victory, for while it was a disaster for the Romans, it also sowed the seeds of Hannibal’s own defeat.

The Tet Offensive

January 30 – September 23, 1968

North Vietnamese and Viet Cong Forces

Commanders: Võ Nguyên Giáp, Nguyễn Chí Thanh

Strength: Estimated 84,000+

Casualties & Losses: Over 50,000 killed

United States & South Vietnam

Commanders: General William Westmoreland, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu

Strength: Approx. 1.3 million allied troops (combined)

Casualties & Losses: Estimated 9,000–14,000 killed

The Tet Offensive is a prime example of a pyrrhic victory, achieved through a widespread, coordinated series of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong attacks on more than 100 cities and outposts in South Vietnam, including the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. It occurred during the Vietnamese New Year celebration of Tet, hence the name. It was an effort to foment an uprising against the U.S.-backed government of South Vietnam and convince the American public that the war was unwinnable.

U.S. and South Vietnamese forces were quickly able to repulse the attacks and inflict significant losses on the communists. However, the surprise and scale of the offensive had a devastating effect on American public opinion and political will to continue the war, as it was portrayed nightly on TV screens across the country. The overconfident General Westmoreland was discredited, and faith in the U.S.’s ability to achieve victory in Vietnam plummeted. President Lyndon B. Johnson decided not to run for re-election, at least partially because of public reaction to the Tet Offensive.

In the end, it can be considered a pyrrhic victory for North Vietnam as it eventually was forced to retreat and suffered catastrophic losses. However, it dramatically shifted the political landscape in the United States against the war. In this way, Tet can be said to be the beginning of the end of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, making it an excellent example of a pyrrhic victory.

The Cost of Pyrrhic Victories

Pyrrhic victories come in many shapes and sizes. As this article has explored, they range from ancient warfare to modern conflicts, from naval battles to political campaigns. Despite their different contexts and consequences, all these examples share one thing in common: they illustrate the Pyrrhic victory paradox. Winning a fight, but losing the war. Achieving a goal, but at a cost that makes it unaffordable or unacceptable. Succeeding, but failing at the same time.

What can we learn from these examples of pyrrhic victories? On a military level, they teach us the importance of strategy, resources, and morale. On a human level, they reveal the complexity of decision-making, the unpredictability of events, and the fragility of victory. Ultimately, they remind us that a pyrrhic victory is no victory at all.