Why Lawrence of Arabia Still Captivates Historians

The Enduring Allure of Lawrence of Arabia

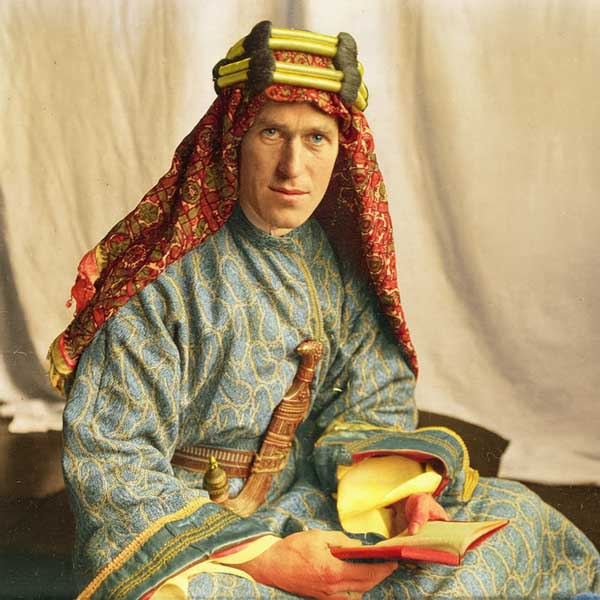

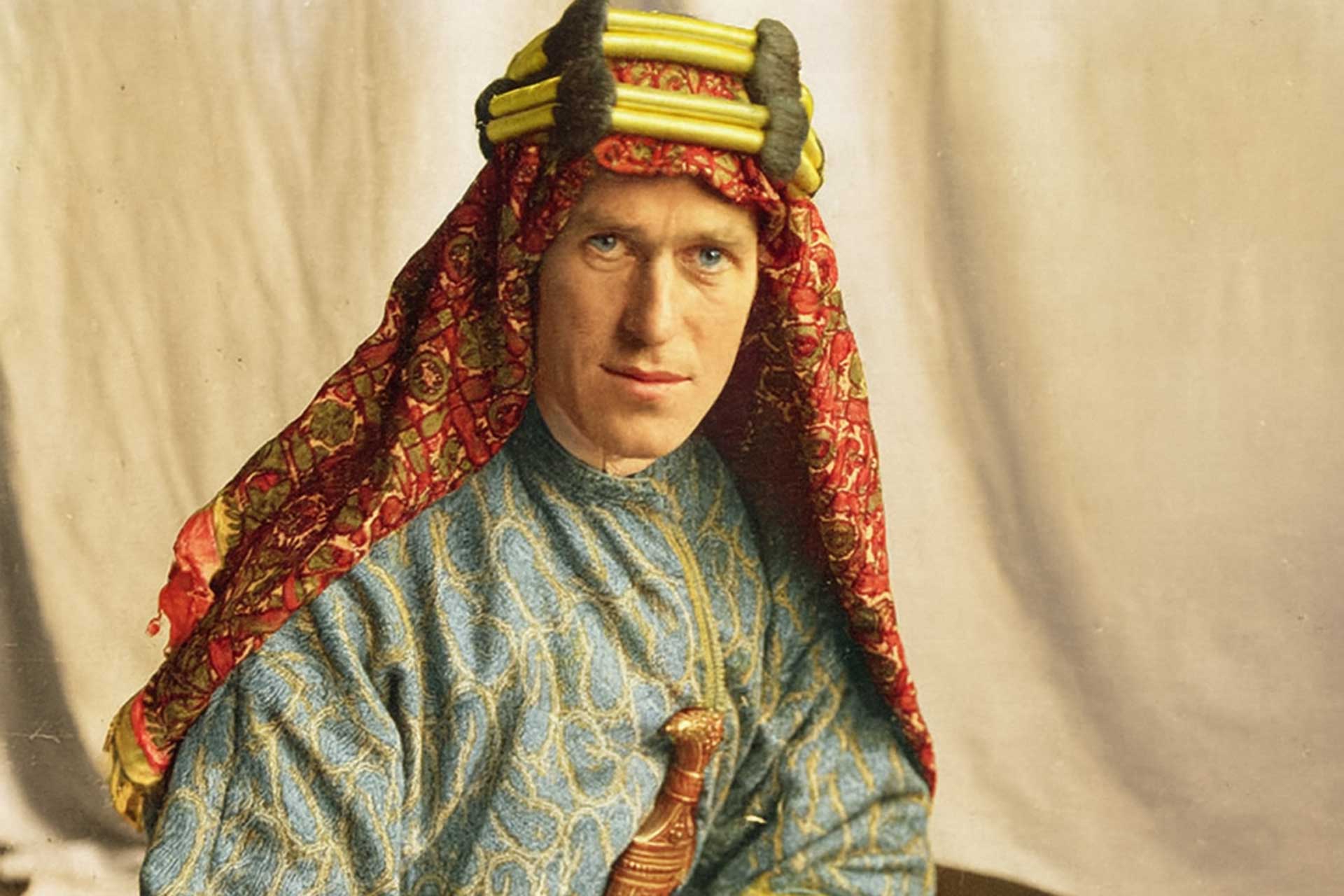

T.E. Lawrence, known to the world as “Lawrence of Arabia,” was a British military officer, archaeologist, and writer whose involvement in the Arab Revolt of 1916–1918 made him an international celebrity. A polyglot who mastered Arabic and lived as a Middle Easterner, Lawrence was famous for leading guerrilla attacks against the Ottoman Empire and for his inner turmoil, which he chronicled in his classic memoir Seven Pillars of Wisdom. A warrior-intellectual and an accidental media sensation, Lawrence is one of the most intriguing figures of the twentieth century.

But one hundred and twenty years after his legend was born, we might still ask: Why does Lawrence captivate? He was a hero of action, an ambassador between cultures, a victim of politics, a reflective writer, and a doomed young man whose life was over too soon. Each side of Lawrence, like all aspects of the man, beguiles, but answers only raise more questions: Why does Lawrence matter?

The Myth and the Reality

The legend of “Lawrence of Arabia” was forged as much in the sensational wartime press coverage and the flamboyant postwar hagiography as in the military campaigns of the Middle East. Reporters like Lowell Thomas and the publicity they generated helped create a T.E. Lawrence image of a veiled Englishman leading desert nomads in majestic cavalry charges, brandishing either a sword or an olive branch.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom and the lavishly produced 1962 film further burnished the popular legend, creating an archetypal Lawrence as romantic, swashbuckling warrior-poet, and almost ethereal in his chivalric idealism. His dashing persona in the service of British arms became a metaphor for a type of Western adventurism.

Lawrence was a talented liaison officer who coordinated British aid to the Arab Revolt, and a daring and resourceful combat leader who masterminded several audacious attacks, including the successful capture of Aqaba in 1917. But he was not, in fact, the only, or even the primary, architect of the victories he is still credited with today. Arab leaders, such as Emir Faisal and other local fighters, often took the lead in operations, with Lawrence serving as a liaison to British interests. He was a significant figure in the conflict, but one whose real-life impact and influence were more collaborative and situational in nature.

Scholars have long grappled with the gap between Lawrence the myth and Lawrence the man. Academic biographies and studies, as well as re-readings of his own published writings, have probed the story to uncover the facts of Lawrence’s exploits during the Great War. Biographers such as Jeremy Wilson and Michael Korda have used personal letters, military reports, and interviews with survivors and eyewitnesses to help separate fact from fiction in Lawrence’s narrative. These investigations often expose a self-critical and conflicted figure, who in private correspondence referred to himself as “a fraud” and was plagued by guilt over his role in the imperialist enterprise.

Lawrence himself added to the mystery by his own actions. In Seven Pillars of Wisdom, he intentionally muddied the line between memoir and creative writing. “All men dream, but not equally,” he wrote, implying that his story was as much about the ideal as it was the actual. This literary self-consciousness has left modern historians with the task of weighing his words not only for their content but also as a construction of his own tortured self-image.

The legend persists, perhaps, because it works. The image of a young Englishman galloping across the desert in the company of Bedouin freedom fighters, flouting convention and championing the cause of Arab self-rule, is both visually spectacular and morally satisfying. The real story, however, is more complicated and less flattering about the conflict, imperialism, and the limits of self-delusion. Lawrence is fascinating to historians, ultimately less for how he lived up to the legend than for how he struggled, and publicly, with it.

In dissecting Lawrence’s mythology, historians will no doubt continue to ask questions about heroism, arrogance, free will, and propaganda. The power of his story, in many ways, lies in that ambiguity, that the man himself was torn by the narrative that had made him a legend. It is in this tension between reality and reputation that the historical significance of T.E. Lawrence may ultimately lie—an emblem of an era that both lionized and unsettled him.

Architect of the Arab Revolt

Lawrence’s most famous appointment was during the Arab Revolt of 1916–1918, when he was a British liaison officer assisting Arab troops in their revolt against the Ottoman Empire. He was fluent in Arabic and had an in-depth knowledge of Arab culture and the region’s topography. Lawrence was able to travel with the rebels, including serving with the forces of Emir Faisal, son of Sharif Hussein of Mecca. Lawrence’s task was to serve as a diplomat who would help to reconcile British war goals with Arab interests.

Lawrence and Faisal developed a relationship that was both pragmatic and, on some levels, real. They collaborated on a plan to wage guerrilla warfare instead of traditional fighting. Lawrence counseled his Arab allies on military strategies that targeted Ottoman supply lines and communication networks- emphasizing mobility, speed, and the element of surprise rather than head-on battles. In his words: “Irregular war is far more intellectual than a bayonet charge.” The most effective of these operations was attacks on critical infrastructure, such as the Hejaz railway, which the Ottomans used to transport troops and supplies across Arabia.

Lawrence’s most famous victory was the capture of Aqaba in July 1917. After an exhausting desert march around Ottoman lines, Arab troops led by Lawrence were able to take the Ottoman port from the landward side, its weakest point. This victory secured an Allied supply line and added to Lawrence’s legend. He later took part in the capture of Damascus, but by that point, other Allied offensives and internal political differences increasingly marginalized him.

While the romantic image of Lawrence of Arabia as a brilliant tactician remains in the popular imagination, many historians emphasize the central role of Arab leaders, such as Faisal, Auda abu Tayi, and others, in making the revolt a success. The Arab commanders had a better understanding of tribal politics and regional geography that drove the campaign more than British contributions did. Historians also debate the extent to which Lawrence was indispensable to the revolt or simply an acute observer and communicator who helped Arab forces make their case to the British.

Nonetheless, his position as a symbolic bridge between Arab leaders and British interests has long fascinated historians. He was neither an insider nor an outsider, but rather existed in the space in between. His status as an agent whom both Arabs and the British could trust is one of the keys to his mystique.

In the end, Lawrence’s importance in the Arab Revolt lies not just in tactics or battlefield victories, but also in the way he represented the complex web of alliances, loyalty, and betrayal during wartime diplomacy. His experience laid bare the contradictions of empire, and those contradictions are part of what has kept historians engaged with his story.

Scholar, Linguist, and Cultural Bridge

Before he became a man of action, Lawrence of Arabia was a student. He went to Oxford and wrote his thesis on Crusader castles, which took him on a journey across the Middle East. He later conducted archaeological research in Carchemish, Syria, with D.G. Hogarth and Leonard Woolley. This scholarly work allowed him to study the languages and cultures of the Arabs long before his military career. He was fluent in both Classical and colloquial Arabic, which allowed him a level of regional insight unmatched by his contemporaries.

Lawrence of Arabia was not like the majority of British imperial agents of his time. He did not look down upon the people or the places he visited. On the contrary, he was enchanted by both, dressing in local clothing and taking part in tribal ceremonies. He developed close ties with local Bedouin chiefs, who trusted and respected him for his authenticity and willingness to share the same deprivations they faced.

In his personal writings, Lawrence described both the desert and its inhabitants with lyrical tenderness and admiration, which was at odds with the racist views about the Middle East that were prevalent in early 20th century Britain. As he wrote in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, “The Bedouin could be a noble friend, treacherous enemy, and always a law unto himself.”

Lawrence was one of the few white men who was able to immerse himself in Middle Eastern culture with such success. In an era marked by colonial arrogance, his cultural insight and fluency gave him a unique vantage point. He could listen to both the British and the Arabs, which allowed him to mediate with a level of authenticity on both sides that many of his contemporaries were not able to muster. Where some officers relied on the simple force of personality, Lawrence used emotional intelligence and persuasion. That duality, the ability to be both insider and outsider simultaneously, has proven rare and is one reason why his memory continues to be valued in the academy.

Lawrence’s cultural knowledge also influenced how the Arab Revolt was reported to and by Europeans. Through a variety of media, from reports and letters to his later written work, Lawrence served as the voice of Arab leaders to a Western world that was largely ignorant of the region. He was able to humanize and articulate the hopes and grievances of Arab forces to an Empire more interested in the spoils of the coming war. In this way, Lawrence transformed a potential footnote of British imperial history into a story of alliance, betrayal, and hope. He was able to bring Middle Eastern politics into the Western public’s consciousness in a way that was deeply personal and human.

The extent to which Lawrence romanticized Arab society and culture remains a matter of debate among historians. However, there is no doubt that his immersion in the region and its cultures, his facility with its languages, and his cultural empathy were unique among Europeans in the 20th century. He did not merely visit the Middle East for professional reasons; he was a conduit for cross-cultural understanding during a moment of dramatic political upheaval. The presence of T.E. Lawrence in the Middle East was not simply functional, but transformational.

Postwar Politics and Betrayal

The shadow of the Sykes-Picot Agreement began to loom over Lawrence’s postwar life. This secret 1916 accord between Britain and France delineated spheres of influence in the Middle East, starkly contradicting the promise of independence given to the Arabs. Lawrence, who had personally pledged British support for an independent Arab state, felt a sense of personal betrayal.

In his later writings, he expresses a profound sense of disillusionment and moral compromise. “We are calling them to fight for us on a lie,” he is said to have confessed to an officer.

The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 offered Lawrence and Emir Faisal a stage to advocate for Arab independence. With the support of some American delegates, they made impassioned pleas. However, the geopolitical and economic interests of France and Britain prevailed. Syria was assigned to France; Palestine and Iraq fell under British control.

Lawrence left the conference world-weary and disenchanted, his faith in political solutions deeply shaken. Faisal’s dream of an independent Arab kingdom evaporated as imperial interests took precedence.

The sense of betrayal felt by Lawrence was profound. He had seen the Arab Revolt as a fight not just for geopolitical goals but for dignity and self-determination. To witness those he had fought alongside so valiantly being abandoned by the very powers that had encouraged their uprising was a source of deep guilt for Lawrence.

In the years following the war, Lawrence largely retreated from public life. He turned down numerous honors and even enlisted in the Royal Air Force under an assumed name. To some historians, this was an attempt at penance. “I gave them my word, and I was not believed,” he wrote, revealing the guilt that gnawed at him.

Lawrence’s political beliefs and intentions remain hotly debated among historians. Was he a true believer in Arab nationalism, acting with admirable foresight? Or were his ideals clouded by romanticism, or perhaps grounded in a more personal sense of betrayal rather than genuine anti-imperialism? Regardless of one’s interpretation, Lawrence’s political legacy is among the most contested aspects of his life.

What is certain is that Lawrence found himself in a unique and challenging position. He was a man caught between loyalty to his homeland and his oath to the Arab leaders who had fought alongside him. His postwar disillusionment has since become emblematic of a larger historical narrative: the betrayal of the Middle East by Western powers.

In terms of the historical analysis of his life, this complex political angle adds a new and deeply human layer to the story of Lawrence of Arabia. He was no longer just a war hero or a master of guerrilla tactics but a figure grappling with the consequences of geopolitical machinations on his conscience.

The paradox at the heart of Lawrence’s legacy—glorious victory overshadowed by the specter of betrayal, hope betrayed by politics—ensures his story’s enduring resonance. It offers a poignant study in the perils of entanglement in imperial politics and the price of compromised ideals.

This was the man historians are coming to terms with, and in a way, this messiness is what makes the figure of Lawrence of Arabia so appealing to the research community.

A Literary and Psychological Enigma

Seven Pillars of Wisdom’s considerable literary value also comes from the many contradictions Lawrence exposed about his psyche within the work itself. From the first edition in 1926, Lawrence’s interpretation of the revolt he helped lead vacillated between expressing pride in what he and the Arabs had accomplished and berating himself for what had, in the end, been a betrayal.

Often, Lawrence the writer would insist that he was not the master of his own fate but instead that he was somehow pulled into the war, almost against his will. “All men dream,” he wrote in one of Seven Pillars’ most oft-quoted passages, “but not equally.” These lines, like many in the book, were later pored over and dissected by scholars eager to understand this deeply flawed, intensely brilliant man.

Lawrence also left behind other pieces of writing, and some accounts of his behavior from those who met him personally, which indicate a tendency toward psychological self-punishment that may have come from personal guilt over the postwar Arab betrayal or from some other source, such as his own struggle with his sexual identity. Lawrence would often enlist under aliases following the war, further stoking a pattern of hiding and self-deprecation that has been mined by biographers since the earliest versions of his life story were published. These facets of Lawrence’s psychological makeup make him only more of an enigma.

Historians continue to be fascinated with Lawrence of Arabia because he was an unusually self-aware participant in the imperial project of his day. He remains an enigma, with a life that reflects the grandest of themes—the morality of war, leadership, questions of identity—and also some of the most intimate ones, like the internal life of a hero and what makes a good person.

His own life reads like an adventure story as well as a highly personal psychological case study; a life lived during one of the more turbulent periods in British history. “Lawrence was not only a man of action,” historian Malcolm Brown wrote, “but a man of vision, consumed by contradictions.”

T.E. Lawrence, the war hero, who had used flamethrowers to destroy his enemies’ positions in the Middle Eastern desert during World War I, who wrote eloquently about his experiences and who was revealed in those writings to be an intensely private man at war with his own thoughts, is the prize. The unresolvable tensions and contradictions, in both his life and his work, are also the draw for historians, for what could be more enticing for those determined to read the past for new meaning than the presence of new material from which to draw new meaning?

Untimely Death and Lasting Symbolism

Following the war, T.E. Lawrence fled his celebrity and the public’s interest in him. Disillusioned by politics and tired of his own personal battles, he left the public eye and enlisted in the Royal Air Force under the name John Hume Ross. Later, he enlisted in the Tank Corps using the name T.E. Shaw. He spent most of his time in service in the modest posting as a Section Commander.

Although he was seen in public, he longed for anonymity and returned to an unglamorous lifestyle far from the Middle East. The level to which he changed his name, adopted false identities, and immersed himself in an unassuming lifestyle has mystified historians, capturing the lengths a man would go to flee his legend.

The life of Lawrence of Arabia was cut short by a motorcycle accident on May 19, 1935. Only 46 years old, Lawrence swerved to miss two cyclists on a road near his cottage in Dorset and was flung from his Brough Superior SS100 motorcycle. The death of such a legendary figure was already symbolic enough, but to meet his end so young and alone only added to the romanticism of his life. Winston Churchill was a particular admirer of T.E. Lawrence and is said to have cried when he heard the news of his passing. For someone who was already approaching a legend in life, death provided that final confirmation.

In the wake of Lawrence’s death, conspiracy theories inevitably began to emerge. Some people started to suspect that British intelligence had killed him to avoid the risk of him publishing his memoirs with the sensitive information they contained. Others speculated that Lawrence of Arabia had faked his own death and assumed a new identity to live out the rest of his life in anonymity. Lacking objective evidence, the persistence of such theories only demonstrates a general inability to let go of this magnetic figure in history. When the facts are unavailable, legend takes over.

Lawrence of Arabia’s early death solidified his place among history’s gallery of “greats who died too soon”. The deaths of Byron and Shelley at young ages already provided a cultural model for future tragic geniuses, to which Lawrence of Arabia fit perfectly. James Dean would die young, and over 30 years later, people would cast him in the same light. This was not the first time the pattern would occur, nor would it be the last.

There is a morbid curiosity to youthful death: we can only wonder what could have been. From this comes the temptation to spin stories beyond the truth, reaching for a level of meaning that perhaps did not exist. For all his genius and self-conflict, Lawrence was human and mortal. But in his death, he was also transformed.

Lawrence’s early death has not closed the book on the life of T.E. Lawrence for historians. If anything, it is the starting point for an increasing obsession with his life and death. Freezing the narrative of his life at a point of climax prompts further research into what came next. By never being fully defined, one is left to continue interpreting, speculating, and investigating a life that is already well-documented. The lack of closure means that new studies on Lawrence appear even today.

In dying young, Lawrence of Arabia has continued to live in history. In death, his legend is no longer of a man but an idea. The concepts of courage and cowardice, integrity and duplicity, contradiction and complexity. It is this inconclusive legacy that will continue to resurrect T.E. Lawrence for as long as anyone remembers his name.

Lawrence of Arabia’s Relevance Across Time

Modern military strategists and tacticians still study the lessons of Lawrence’s campaigns. His concepts of mobile defense, morale, and unconventional warfare, detailed in military training institutions, continue to be taught and debated. He once wrote, “Irregular warfare is far more intellectual than a bayonet charge,” and that understanding of the nuanced and cerebral nature of war has permeated military thought.

Politically, Lawrence’s life is a prism through which current issues in the Middle East are sometimes viewed. His forewarnings about the consequences of sidelining Arab independence have an unsettling echo in today’s geopolitical quagmires, where foreign powers intervene and promises to local leaders are not always kept. The postwar order he helped create, following the fall of the Ottoman Empire, is scrutinized by historians and politicians alike as they navigate the region’s shifting sands.

The fabric of popular culture keeps Lawrence of Arabia relevant to contemporary audiences. David Lean’s 1962 cinematic epic not only immortalized his story but also became a cultural touchstone for generations. Beyond the silver screen, books, documentaries, and plays continue to explore his life, ensuring his story remains part of the public conversation. In these retellings, Lawrence is as much a creation of the times as he was a shaper of them.

Scholars have only recently been granted full access to Lawrence’s personal archives. This treasure trove of correspondence, personal reflections, and military documents is reshaping our understanding of him. The authenticity of his narrative is being dissected, and the once untouchable legacy is now open to academic debate. Revisionist perspectives are emerging, challenging the traditional hero narrative and offering more nuanced interpretations.

Lawrence’s legacy is as varied as the periods that reinterpret his story. For the current generation facing the challenges of nation-building, insurgencies, and shifting alliances, he may serve as a template for a new type of soldier—one who is both a warrior and a scholar, at ease in both the world of arms and ideas. This image of Lawrence provides fodder for debate on many modern issues, from the merits and ethics of intervention to the practicalities of counterinsurgency and counterterrorism.

The figure of Lawrence of Arabia has an uncanny way of staying relevant because he seems to be moldable to a certain extent by any generation that chooses to make him. Whether as a historical example or a cautionary tale, he serves as a benchmark for discussions on foreign policy and military ethics. And in a world where many of the questions we face are in some ways the same as those faced over a century ago—conflict and nation-building, insurgencies and terrorism—it’s no surprise his story resonates.

The Enduring Enigma of Lawrence of Arabia

Lawrence was a scholar, soldier, diplomat, and writer. He was also all of these things and much more, and for many of us, that much more is what he remains. A few things about Lawrence are simple or easy. He was the stormy driver of the Arab Revolt; the romantic champion of Arab independence; and the eloquent philosopher and existentialist of his war memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom. In a literal sense, he was all of these things. On a more personal level, as often happens with historical figures, the events that made Lawrence a major player in the final stages of the Ottoman Empire were marred by tragedy and frustration.

Lawrence’s fame and his continued presence in our lives are intricately intertwined with the symbolic power of his actions. From the success of his revolt to the circumstances of his death, Lawrence remains a figure who continues to offer us a vehicle for exploring ideas. By this token, the “Lawrence of Arabia” of today is also a figure who means different things to different people: the enduring enigma, the frustrated imperialist, the thinker behind Seven Pillars, the fighter for Arab independence, and so on. The continuing relevance of these ideas is therefore assured, as is Lawrence’s presence in our culture and his claim on our attention. For good or ill, in the final analysis, T.E. Lawrence was history.

![Lawrence of Arabia (Restored Version) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/4113z3R3KnL.jpg)