Xenophon and the Ten Thousand: Ancient Greece’s Greatest Retreat

In the year 401 BCE, 10,000 Greek mercenaries became stranded in the heart of the Persian Empire. Betrayed and without their employer Cyrus the Younger, who was killed in the Battle of Cunaxa, they retreated across the region and were forced to trek their way back home. Their story is told from the first-hand experience of one of their own, Xenophon, in Anabasis.

The long trek home had to be forced through barbaric landscapes and hostile forces. From beginning as a potential coup to place Cyrus on the Persian throne to their forced return home, the trek of the Ten Thousand became a journey of pure survival against the elements and a desperate need to live to see their families.

Why Were Greeks in Persia?

The Peloponnesian War, fought between Sparta and Athens (431–404 BCE), had left Greece politically divided and economically shattered. Professional soldiers were left unemployed and purposeless at the end of the war. The Greek mercenary, armed and ready to fight, but without a state to work for, had been created. After the war, mercenaries and a small pool of free, able-bodied men were available for foreign states to purchase. Persia was one such state, and it was vulnerable to attack as it was embroiled in a civil war of succession.

Cyrus the Younger was the Persian satrap of Lydia and a prince of the Achaemenid Empire. He was a warlike and ambitious prince who was in a power struggle with his older brother, the Persian king Artaxerxes II. Cyrus discreetly began recruiting and gathering over 10,000 Greek mercenaries and soldiers by offering generous pay. He was able to march a foreign army into the heart of Persia by deceiving them about his destination and the true purpose of the force. Cyrus was using the ruse of being put in charge of suppressing rebellions in Asia Minor. He was secretly amassing an army to march on the Persian capital of Susa and seize power for himself.

The resulting Greek mercenary force came to be known as the “Ten Thousand.” It was dominated by hoplites (Greek heavy infantry) who had survived the twenty-seven years of warfare fought by the Greek city-states. The “Ten Thousand” also included peltasts (light infantry) and mercenaries from other nationalities. The “Ten Thousand” Greek soldiers who made up the core of the force had many different reasons for enlisting in the mercenary army. Adventure and a chance to make a name for themselves and riches on the battlefield were attractive to many of the Greek mercenaries.

Additionally, many of the Greeks enlisted had come from Sparta’s former allies or war-ravaged states that were in economic and social ruin. As a group, the “Ten Thousand” had great potential because of their cohesion. They were a Greek force under Greek officers who had been elected and had a superior esprit de corps to the Persians. They were confident of their own superiority as well as in the superiority of their weapons and equipment. The result was an army with great potential to be an effective and cohesive fighting force in the field.

For the Greeks, a long and dangerous road lay ahead, marching deep into Persian lands far from their homeland. The journey evolved into a legendary retreat as the Greek mercenaries had to fight their way through enemy territory in one of the most famous last stands in history.

The Battle of Cunaxa and the Crisis

The Greek mercenaries were finally met by the full force of the Persian king in 401 BCE at Cunaxa, near Babylon. The Greeks were heavily outnumbered, but they managed to hold their ground on the right flank of the battle line. In a textbook display of tactical formations and battlefield discipline, they pushed back Persian waves with superior strength and tactics. As the Greeks advanced, the Persian leadership appeared to be in full flight, and the enemy army began to rout. Victory for the Greeks was at hand, but not in the way that they had intended.

The true battle was over whether Cyrus would be successful in his plan, and he would be declared the victor only if he won. In a rash attempt to win the battle, Cyrus had charged at the phalanx formation in a direct attack on his brother Artaxerxes. In doing so, he was mortally wounded and died on the battlefield. As the tide had turned, the battle for Cyrus was lost.

Although the Greek mercenaries had done well in battle, the objective for which they had fought was now in disarray. Cyrus was dead, and the army he had gathered and paid for was leaderless. The Persian army was very much still intact, and the Greeks had no stake in the land, no spoils, and no local allies. The 10,000 had marched over a thousand miles away from their homes and were now left with no clear mission or patron as a result of Cyrus’s death.

The Greeks had initially asked for the right to march home, and this was quickly arranged. The Persian satrap, Tissaphernes, feigned diplomacy and requested a conference with the Greek generals, stating that he wished to honor them for their victory. He sent an envoy to the Greek generals, inviting them to his tent to agree.

In reality, it was a trap. Tissaphernes invited only the top Greek officers (six in total) for a ‘friendly’ meeting in which he had his men ambush and kill them all. The generals were taken by surprise, and Clearchus, the Spartan, was killed on the spot. With the top leadership of the army now dead, the soldiers were left with no direction and in a horrible situation.

The Ten Thousand were now in a state of panic. They were in the middle of enemy territory, far from any friendly forces, and their best and most trusted leaders had been killed. Rumors of impending doom and other such stories spread among the troops. Many believed that their end was nigh and that the Persian king would either slaughter them all immediately or slowly starve them out in the interior of his empire. However, a remarkable turnaround, unprecedented in ancient warfare, was about to begin as one of the most unknown Athenians took a chance and managed to win over the men.

Xenophon’s Rise and Leadership

The army was on the verge of disintegrating. The generals were dead, and the soldiers demoralized. In this crisis, the voice of one junior officer rose above the rest. Xenophon was an Athenian and had no legitimate authority to command the Greek army. In fact, he had not even been a soldier previously. He had served as a student of Socrates and took on the campaign as something of an adventure. He wanted to see this army and hear what this Cyrus would say to the soldiers. Xenophon possessed a remarkable gift for leadership that shone particularly in times of crisis. He had intelligence and an even temperament, but above all, he had a talent for speech, and it was this that came to the army’s aid now.

Xenophon recounts in the Anabasis that he was encouraged by a dream the night before in which Zeus commanded him to take action. The next morning, he spoke to the remaining officers and soldiers, exhorting them to have courage and hold together. The Ten Thousand should not expect to be shown mercy by the Persians. It was up to them to survive. “The gods have not forgotten us,” he said.

He inspired in them a vision of Hellenic martial excellence favored by the gods. He promised to find a solution and provided a tactical plan. They should break the army into smaller companies that would be more mobile and able to protect one another. The leadership of these groups would be elected, and Xenophon made it a point that no one person would be able to dominate the others. The plan was adopted and Xenophon’s authority established. The army was reorganized with closer marching order and defensive formation, and councils were held daily to make the decision-making process more transparent.

The Ten Thousand were on their way again, marching west, not with dreams of riches, but with thoughts only of home. They had a path forward, and Xenophon would lead them to it. Xenophon found a solution to the crisis, becoming a tactical and moral leader for soldiers who had lost their generals, patron, and reason to fight.

The March Through Enemy Territory

The journey of the Ten Thousand was arduous and fraught with peril. Marching north through unknown Persian lands, they were beset on all sides. Harsh terrains tested their limits: steep mountains, rapid rivers, and snowy passes. Crossing into the Armenian highlands and the land of the Carduchians, the Greeks struggled up icy and rocky paths, often without food or shelter.

The local inhabitants launched frequent attacks. The Carduchians, fierce mountain tribesmen, harassed the Greeks from higher ground. Xenophon’s men found themselves fighting daily skirmishes. Later, Armenian cavalry and Persian forces repeatedly tried to cut off the army’s route. Through phalanx formations, tactical retreats, and staggered marches, the outnumbered Greeks used every advantage to evade their enemies. Xenophon’s knowledge of the terrain and emphasis on discipline and unity allowed his army to survive without descending into anarchy.

The logistical challenges were overwhelming. Cut off from any supply line, the soldiers subsisted by foraging, bartering, and sometimes seizing food by force. Hunger, cold, and exhaustion eroded their spirits, but Xenophon worked tirelessly to maintain discipline. He held daily councils and meted out public punishments for cowardice or desertion. Emphasizing shared leadership and strategic pauses to rest and regroup, Xenophon maintained unity and morale. One of his crucial tactical decisions was placing light-armed troops and slingers in the rear-guard to fend off ambushes and protect retreating forces.

After months of grueling struggle, salvation finally appeared on the horizon. The army reached a mountain pass near the city of Trapezus, on the shores of the Black Sea. From the summit, they caught their first glimpse of open water. A cheer erupted down the slope: “Thalatta! Thalatta!” (“The Sea! The Sea!”). It was both a geographic and a psychological victory. The sight of the sea meant food, safety, and the possibility of a return home. That moment of jubilation and relief has been immortalized in Xenophon’s Anabasis.

Return to the Greek World

After a long and bloody journey, the Ten Thousand finally reached Trapezus, a coastal Greek city on the Black Sea. After the trek through the mountains, it was a time of celebration. Trapezus, located in modern-day Turkey, was a port that provided the Ten Thousand with a respite from the road and a connection to the Greek maritime world. The Greek locals in Trapezus greeted them with food and religious festivals. Xenophon led sacrifices to the gods to give thanks for their salvation, and the army rested and regrouped.

Their return journey, however, was not over. There were immediate political challenges. There was no longer an employer, since Cyrus had been defeated and was dead. There was also no central leadership. The Greek poleis were divided and could not agree on a plan for the future. Arguments arose over pay, alliances, and oaths. One side wanted to get involved in the local wars and profit from them, while the other wanted to return home immediately. Xenophon was respected, but not immune to criticism and complaints about his power.

Divisions in the army grew as they continued their march westward along the coast. Arguments over who should lead, how to supply themselves, and what course to take fractured the army. Some groups of soldiers made it back to their home city-states, but the return was not a unified one.

The Ten Thousand’s journey finally came to an end. A final glorious battle and triumph did not mark their return. Instead, they demonstrated that even against great odds and treachery, a well-ordered army can return home.

Xenophon’s Life After the Retreat and the Legacy of the Anabasis

In the years following the miraculous retreat of the Ten Thousand, Xenophon’s reputation grew not only as a survivor and military leader but also as one of the most important intellectual voices of his time. He had no formal command at the start of the campaign in Asia. Still, when his superiors and generals died, his leadership ability became undeniable and earned him a respected place in history. Due to his support of Sparta, Athens’ main enemy during the Peloponnesian War, Xenophon was exiled from his home city. He settled in Scillus, a small town in the Peloponnese, and lived there under Spartan patronage, continuing his studies in philosophy and writing.

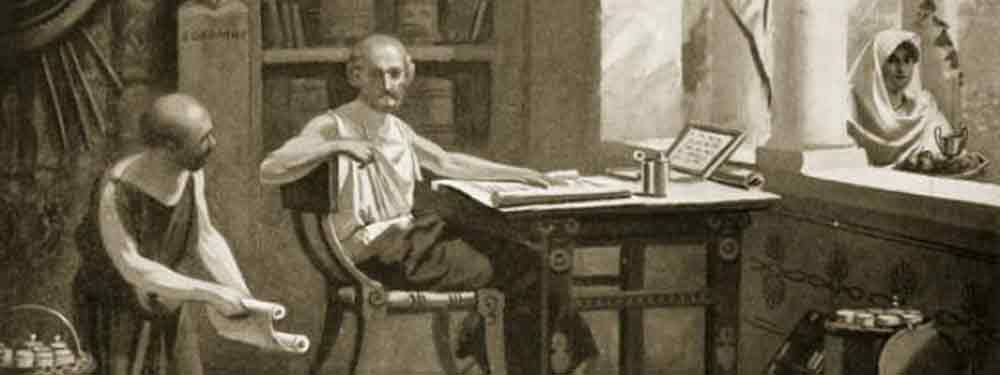

The most significant work to come from Xenophon was Anabasis, a detailed narrative of the whole campaign and retreat from within. It was written in the third person and combined a military narrative with personal reflections on the nature of leadership, decision-making, and ethics. Xenophon’s account is remarkable for its personal detail, which focuses not only on external threats to the army, such as the Persians, geography, and hunger, but also on internal discipline, cohesion, and morale. The work was one of the first and certainly one of the longest-surviving examples of autobiographical military literature, and it is still studied today for both its content and the use of rhetorical devices.

In other works, Xenophon also wrote on Socratic philosophy (Memorabilia), politics (Cyropaedia and Hellenica), horsemanship, and household management. Throughout his works, a common thread can be found in his emphasis on leadership, virtue, and a kind of practical wisdom or pragmatism. Xenophon was known for his high regard for Sparta and the Spartan discipline and organization, which he admired as a means to achieve a higher civic order. This is remarkably well detailed in The Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, where he contrasts the Spartan system with the governance of other Greek states. Xenophon would go on to live and write under Spartan patronage for the rest of his life. Xenophon’s own philosophical interests were clearly not with the idealism of Athenian democracy, but more with the pragmatic side of statecraft.

The retreat of the Ten Thousand had long-lasting military consequences. Xenophon’s experience and his behavior at that time were held up as an example of clear thinking under pressure and moral responsibility to one’s men by military leaders for centuries. It is said that Alexander the Great read the Anabasis during his own campaigns, seeing it as both a tactical guide and a philosophical text. The idea that even an outnumbered and outmatched army could, through discipline and cohesion, survive against impossible odds in hostile territory was decisive for centuries.

As much as the campaign made Xenophon a soldier and a man of action, his study of philosophy gave his version of events a uniqueness in historical literature. The Anabasis is one of the rare texts in which a commander and the experiences that made him a general have shaped their own narrative for future generations to understand. It remains a classic in the study of classical leadership. The Ten Thousand lessons of discipline, flexibility, and moral fortitude in the face of the unknown lived on through Xenophon’s words and continue to inform leadership and the human spirit to this day.

Conclusion: Legacy of a Reluctant Hero

Xenophon’s leadership exemplified small-unit command and control at its most effective. Suddenly finding himself without a commander, he had no preparation for this role. He assumed leadership of a desperate and demoralized force in enemy territory against tremendous odds, and by his abilities, held them together and brought them home. Xenophon’s military successes are primarily due to his inspired leadership of the mercenaries.

Having the courage and ability to keep men alive without being an appointed leader demonstrates the qualities of a great leader. Xenophon’s organization and intelligence allowed the Greeks to travel with discipline, unity, order, and hope through great and growing danger. This in itself is no mean feat, but Xenophon’s determination to be unswerving in his leadership and mission, despite treachery and alienation, shows a leader who has the potential to win men’s hearts and minds, and inspire greatness.

The March of the Ten Thousand has been a byword for heroism, cunning, and Greek valour, as recorded in the Anabasis. As a story of endurance against the odds, it is perhaps one of the most human and moving of military legends. The actions of Xenophon and the remaining army are one of the most famous retreats in history, and are still seen as one of the greatest military stories of all time, over 2,000 years after it occurred.