11 Fascinating Facts from the First Thanksgiving in 1621

The story of the first Thanksgiving in 1621 has long captivated people across the United States. The American tradition of celebrating Thanksgiving began that autumn in 1621 with events that both myth and legend and historical fact have since surrounded. The often-romanticized image of Pilgrims and Native Americans breaking bread together at a large harvest feast, though a cornerstone of popular culture in the United States, is a mystery as much as a tradition.

In truth, moving past the modern story of Thanksgiving, as told by generation after generation, is fascinating in its detail when it comes to the early settlers, the Native Americans who supported them and helped them, and the actual events that occurred that year during the holiday’s origins in Plymouth Colony.

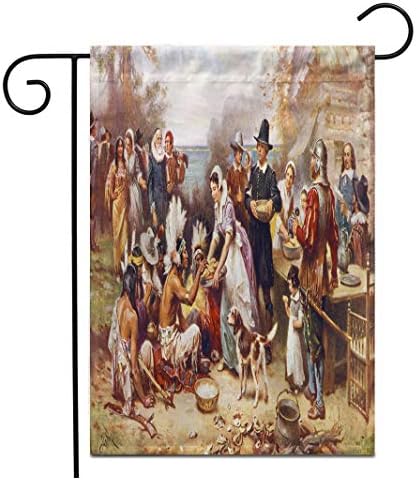

The popularly held image of Pilgrims and Native Americans sharing the first Thanksgiving feast is, for many people, second nature and ingrained in their psyche. The story is compelling and straightforward, but the reality of the 1621 Thanksgiving feast was not only more complex but also quite different. Instead of a communal meal, what actually happened was a three-day celebration of survival, adaptation, and cooperation between the settlers and the Wampanoag people.

The Length and Timing of the First Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving Day celebrations were more of a harvest festival, and lasted for more than one day. Despite popular belief, the first Thanksgiving was not a one-day affair. Historical accounts indicate that the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag celebrated for three days in 1621. Both Native Americans and Europeans held harvest festivals for several days.

The Pilgrims had much to celebrate after a long and challenging first year in the New World. They were fortunate to have a good harvest and the Wampanoag to help them. The Indian tribe, led by Chief Massasoit, swelled the celebration crowd.

Although no one knows the specific dates of this first feast, most historians agree that it probably took place in late September or early October. This would also be more in line with the traditional harvest time. During these three days, they feasted and took part in games, singing, and even some military exercises. For a brief moment, the Pilgrims and the Native Americans coexisted in peace and harmony.

The Crucial Bond: Pilgrims and the Wampanoag Before 1621

The first Thanksgiving feast took place in 1621 to celebrate the Pilgrims’ first successful harvest in the New World. However, it was long before this famous feast that the Plymouth colony began to develop friendly relationships with the neighboring Native Americans. When the Pilgrims first settled in the New World in 1620, they were in need of preparation for the changing weather and getting a better understanding of how to farm on the land.

The local Wampanoag Native Americans, including their chief, Massasoit, came to the aid of the Pilgrims to help them survive in the New World. The Wampanoag people showed the pilgrims how to farm and grow vegetables such as corn, beans, and squash, and even how to fish and hunt for the wide variety of animals and birds on the land.

The Indians took this action as a sign of peace and developed an alliance with the pilgrims in the forming colony. The Wampanoag were suffering from European diseases and the wars with their rival Indian tribes. In the forming colony, the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims signed a treaty of peace and protection from the other Indian tribes in March 1621. The Thanksgiving feast in November 1621 was a sign of the success of this treaty, being a way to thank each other for the help and the plentiful harvest.

A Gathering of Cultures: The Attendees of the First Thanksgiving

This first Thanksgiving in 1621, as history would have it, was remarkable in both the celebration and the attendance. It was mentioned that around 50 Pilgrims and 90 Wampanoags were in attendance. The attendance is astounding, given that the Pilgrim population had been reduced to only about half of the original Mayflower passengers by the fall of 1621. The Wampanoags’ strong turnout and the powerful presence of their leader, Massasoit, speak volumes about the Wampanoags’ goodwill and the strong relationship between them and the Pilgrims.

The large Wampanoag attendance, outnumbering the Pilgrims 2:1, is a testament to the vital role they played in the survival and founding of Plymouth colony. The attendance, given these two groups of vastly different backgrounds, is a symbolic commemoration of this early period of peace between them.

The Feast of 1621: A Different Thanksgiving Menu

The menu of the First Thanksgiving in 1621 included foods that differed significantly from those of a modern traditional Thanksgiving meal. The meal likely included venison and wildfowl. A good description of the foods that would have been at the First Thanksgiving, including the likely dishes prepared for the meal, comes from the account of Edward Winslow, a leader of the Plymouth Colony. This account, along with other evidence of the time, makes it clear that the meal would have included these foods.

The menu would have included venison and wildfowl. Waterfowl at the time included ducks and geese, as well as wild turkeys that were native to the area. These meats would have been the protein centerpiece of the meal. The meal’s menu also included native vegetables and staples. The Pilgrims learned from the Wampanoag how to grow corn, which was a critical crop for them. A probable preparation for the meal was cornmeal, as well as breads made from it.

The meal menu also included shellfish, such as clams and mussels, since the settlement was coastal. Squash was another crop the Pilgrims learned from the Wampanoag, and it is another logical possibility for the meal’s menu. Potatoes were not yet widely grown in North America. Pumpkin pie was also not on the menu because the Pilgrims did not have the butter and wheat flour needed for a pie crust.

The Wampanoag Contribution: Venison and More at the Feast

The Wampanoag guests contributed five deer to the feast, a large and generous donation given the circumstances. This venison contribution from the Wampanoag tribe was an important and memorable addition to the first Thanksgiving feast of 1621, enriching the variety and quantity of food available. The offering of deer by the Wampanoag guests symbolized goodwill and the cooperative relationship that was being forged between the Pilgrims and the indigenous people of the region.

In addition to providing deer, the Wampanoag made several other significant contributions that were crucial to the first Thanksgiving and the Pilgrims’ overall survival in the New World. They shared their knowledge of local agriculture, including how to cultivate and harvest indigenous crops, which was essential for the Pilgrims’ adaptation and survival. The Wampanoag also taught the settlers fishing and foraging techniques, further supporting their sustenance. The presence of the Wampanoag at the first Thanksgiving was a gesture of sharing their culture, knowledge, and resources with the Pilgrims, marking a moment of unity and cooperation.

The Essence of Harvest in the 1621 Celebration

The First Thanksgiving of 1621 is a momentous occasion that has become etched in history. Popular narratives might depict it as a solemn religious gathering, yet the reality was quite different. This celebration primarily focused on giving thanks for a successful harvest rather than on a religious ceremony. The Pilgrims’ joyous feast stemmed from the immense relief and gratitude they felt after enduring a grueling first year in the New World, where the successful harvest marked the turning point that had ensured their survival. As a result, the 1621 Thanksgiving was more akin to a traditional English harvest festival, infused with celebratory feasting and communal revelry, rather than a solemn religious service of Thanksgiving.

A feast of harvest is bound to contain elements of the cultures of all those who contributed to it. In 1621, the English Pilgrims and the Wampanoag Indians joined together to give thanks for the land. This amalgamation of two cultures could easily create a jarring of traditions, as both had different methods of celebration. The English Pilgrims would have already had a taste of Harvest Home, a traditional English celebration marking the end of the harvest.

However, this was not a one-sided cultural celebration, as the Wampanoag also held a harvest celebration. Traditionally, this was a time for dancing, singing, and feasting to thank the land for its abundance. Due to the varied cultural practices at the first Thanksgiving, it became a one-of-a-kind celebration that brought together multiple customs in a spirit of happiness and gratitude.

The Evolution of Thanksgiving into an Annual Tradition

Thanksgiving did not occur the year after the original 1621 harvest celebration, but it took time to become an annual tradition. The idea that Americans need to share a turkey meal every November is a persistent myth that has slowly distorted the historical significance and meaning of this tradition. Thanksgiving as a national holiday is rooted in the Pilgrims and Native Americans tradition of celebrating successful harvests with a feast.

It took centuries for this tradition to become an annual event that all Americans celebrate on the fourth Thursday in November. The Pilgrims and the Wampanoag celebrated Thanksgiving at Plymouth Plantation in 1621. Still, this feast took several decades to become a regular occurrence, a tradition that would need some cultural and historical ingredients to reach its current form. Sarah Josepha Hale, the author of the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” helped shape this tradition. Hale was a tireless campaigner for Thanksgiving, helping make it a national holiday. She used the popular “Godey’s Lady’s Book” as a political platform to publish editorials in favor of this celebration.

She would also send numerous letters to political leaders asking them to make this tradition a national holiday. Hale was finally successful. Abraham Lincoln proclaimed Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863. During the Civil War, Lincoln used the proclamation to unite the country’s citizens. He set the celebration for the last Thursday in November, which made it a day of praise and Thanksgiving.

The Origins of the Term “Thanksgiving”

Ironically, the Pilgrims did not actually refer to the 1621 feast as “Thanksgiving.” Instead, the way they marked the event as it happened was more similar to an English harvest festival. Harvest festivals were (and still are) community events held at the end of the harvest season to celebrate a successful crop gathering. For the Pilgrims in 1621, the third week of November marked a time of celebration after a long and difficult year. There was no shortage of work during that first year, and the celebration was about more rejoicing in a successful harvest than it was about “giving thanks” in a religious sense.

The Pilgrims would have enjoyed the feast as a reminder of the blessings to come in the winter. The holiday we know as Thanksgiving underwent a gradual shift in meaning away from that first historical event, along with the addition of new traditions and practices to the celebration. As the story of the first Thanksgiving was retold from generation to generation, its meaning shifted to one of peace, cooperation, and giving thanks. The name “Thanksgiving” came to be used for other fall celebrations, and eventually, the holiday came into being as we now know it.

Dining Etiquette at the First Thanksgiving: No Forks Allowed

An interesting fact about the first Thanksgiving in 1621 is the serving utensils and the way the pilgrims and Wampanoag ate at this first harvest celebration. The first interesting fact here is how and with what utensils they ate. We can easily guess that no forks were used, since they did not exist for the pilgrims or in England generally at the time. Knives, spoons, and fingers were available for eating different foods. Forks in Europe were uncommon and would become common several decades after the event. This meant eating during the first Thanksgiving was a hands-on affair. Participants would use their knives to cut meat and probably spoons to eat softer foods like corn porridge or stew.

Other related facts about the first Thanksgiving include serving and preparing the meal. There were certainly English influences on how food was prepared since the Pilgrims were in a new land and had the help of Native Americans. Some preparation, such as roasting meat over a fire, would have been done by the Wampanoag. In contrast, boiling and stewing were part of the Pilgrims’ English heritage.

Also, with no ovens available for baking, there was no bread or pie at the first Thanksgiving celebration, unlike our modern holiday. Bread and pastries are typical on our modern table. Other facts about serving at the first Thanksgiving included the meal likely being served communally. Food was set out on the table for all guests to serve themselves. The sharing of food reflects both the community-centric culture of the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag customs for dining together.

Earlier Thanksgivings in America

The 1621 Plymouth feast has been traditionally described as the “First Thanksgiving” in the future United States. However, this is not technically true: numerous Thanksgiving services had been held by Spanish explorers in Texas and Florida several decades earlier.

The first Thanksgiving mass in the future United States was conducted by Spanish explorer Pedro Menéndez de Avilés in St. Augustine, Florida in 1565. A Spanish Thanksgiving also occurred in 1598 along the Rio Grande in Texas, when Juan de Oñate’s Spanish colonists and indigenous scouts held a Thanksgiving celebration after enduring an 80-day desert crossing to arrive at the Rio Grande in Texas. Unlike the Plymouth harvest festival, these celebrations were primarily religious in character, involving the giving of thanks through masses and prayer rather than a feast.

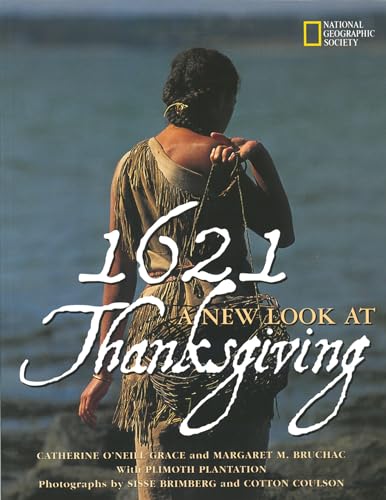

The Scarcity of Primary Sources on the First Thanksgiving

A curious, unique factor about the First Thanksgiving in 1621, which distinguishes it from all subsequent festivities held in its name, is the limited documentation of the historical event. Only a select few primary sources recount the event in detail, with the most comprehensive account coming from a journal entry by Pilgrim Edward Winslow. Winslow’s account included what he did and who was present to celebrate the feast. While his journal included firsthand accounts of the first Thanksgiving, it was shockingly short for such a monumental event.

Winslow’s description of the historical event detailed that he and his community members enjoyed the company of Massasoit and his men, who had brought deer to join the celebration. Winslow also included a brief overview of the different activities that took place during the celebratory period. The Pilgrims used the time to entertain their Native American allies and to stage shooting exhibitions as a show of force.

Winslow’s journal devoted few words to the event itself. The few available primary sources paint the picture of a feast shared between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag, though many details are lacking. There are just not enough descriptions of the event for historians to have anything more than an incomplete sketch of the first Thanksgiving. This is also what causes so much of the modern retelling of the story to be a blur between tradition and myth.

Reflecting on the Legacy of the First Thanksgiving

The first Thanksgiving in 1621 is an important historical event of the United States and has its own distinctive and rich history. The first Thanksgiving has been sparsely covered in historical literature due to a lack of sufficient written sources, and it was mainly based on documented tales and local myths. However, no matter the sources of this story, the First Thanksgiving in 1621 was a significant moment in American history and culture, and a powerful source of American historical mythology that is celebrated every year on Thanksgiving.

It is part of the history of the United States to understand the story of the First Thanksgiving in 1621 and its importance for the United States from historical and cultural perspectives. Since the story of the First Thanksgiving has involved more actual information than not, it is important to spread awareness of what actually happened in 1621 to give credit to the Native Americans and to understand where the United States’ national holiday and tradition come from.

Moreover, since the story of the First Thanksgiving is not entirely based on the actual historical record but instead covered in documented Native American stories and local American tales, it is an opportunity to look at how a specific important event in history can actually lead to the formation of a rich story and a mythology that adds value to the historical record.

Thank you for the interesting article! I was told some people feel thanksgiving is a day of mourning. I disagree, gratitude is a much needed attitude in our society.

A “traditional harvest festival” was not non religious – on the contrary it was a religious event, and still is.

Yes , I believe it was a Thanksgiving to God , as the Mayflwer Compact , they said clearly , that they came clearly for the proclamation of the Christian faith . And also , not much , was given of Mr. Winslow’s comments in his journal . And how they thanked God ,on the shore that they had arrived safely , to their destination .