The Tale of Pierre Terrail, Chevalier de Bayard: the Last True Knight

Chevalier de Bayard, a name that conjures images of bravery and pristine chivalry, stands immortalized in the annals of history as the embodiment of the knightly virtues. His tale weaves through the tumultuous tapestry of the Italian Wars, a period marked by the clash of empires and the quest for territorial dominion. Yet, amidst the cacophony of clashing swords and the machinations of power, Pierre Terrail emerged not merely as a warrior of repute but as a paragon of honor. He fought not for personal glory but for the ideals that the title of knighthood represented. When the concept of chivalry began to wane in the face of gunpowder and cannons, Bayard shone as a beacon of the old ways, the last of a dying breed who carried the chivalric code in both heart and deed.

His life’s story is a chronicle of courage, a narrative that unfolds with each battle, each act of gallantry, and each display of unwavering loyalty to his sovereign and his code. Known as ‘the knight without fear and beyond reproach,’ Bayard’s exploits on the battlefield were matched only by his magnanimity and adherence to the chivalric code. From the snowy passes of the Alps to the sun-drenched fields of Italy, his legend grew with every encounter, captivating the imaginations of those who yearned for a hero in an age of uncertainty. In this recounting, we delve into the life of a man whose legacy outlasted his era, a true knight in both title and spirit.

The Ascendance of a Knight: Pierre Terrail’s Early Years

In the shadow of the French Alps lay the Château Bayard, within whose stone walls the future Chevalier de Bayard, Pierre Terrail, was born. Heir to a lineage steeped in martial tradition, Bayard entered a world where the courage of his ancestors was etched into family lore, with three preceding generations having fallen in battle, their legacies spanning from the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 to the conflicts that marked the fifteenth century. This heritage of honor and warfare coursed through Bayard’s veins from his earliest days in the Dauphiné region, where the whispers of his forefathers’ bravery were as constant as the mountain winds.

As a page, Bayard’s days were spent in the service of Duke Charles I of Savoy, a tenure that would be cut short by the Duke’s untimely death in 1490. However, during this period, the young Pierre Terrail’s destiny began to unfold. At the tender age of thirteen, he demonstrated such an extraordinary skill in horsemanship before the Duke of Savoy that it earned him the moniker “piquet,” a testament to his prowess with the spur. This display caught the eye of King Charles VIII of France, marking the beginning of Bayard’s ascent in the royal court.

Bayard’s charm, striking appearance, and talent in the tiltyard were noticed, and soon, he found himself serving as a man-at-arms under Louis de Luxembourg, Seigneur de Ligny. It was a position that offered young Bayard proximity to the French king and a stage on which to demonstrate his nascent martial talents. His reputation grew when, in July 1494, at a grand tourney in Lyons attended by the king and his court, Bayard, not yet eighteen, triumphed over seasoned knights, winning the highest honors and royal commendation.

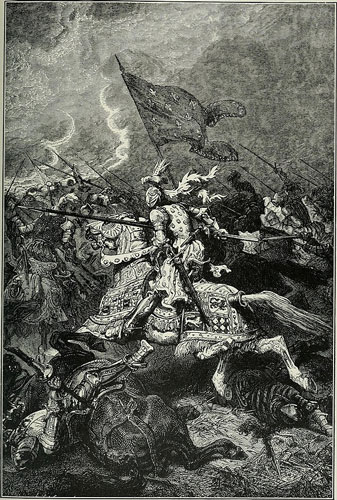

The Italian War of 1494–1498 saw Bayard accompanying Charles VIII in the ambitious endeavor to claim the Kingdom of Naples. During the Battle of Fornovo in 1495, Bayard’s chivalric destiny was cemented amidst the tumult and clamor. In the heat of combat, he seized an enemy standard, an act of courage that would see him dubbed a knight on the battlefield.

His zeal led him to pursue the retreating foes into Milan, where he was captured. In a remarkable turn of events, Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, released him without a ransom demand, struck by Bayard’s bravery and nobility. Though Charles VIII would retreat from Italy, relinquishing his conquests, this campaign laid the groundwork for further Italian adventures. It heralded the illustrious career that awaited the Chevalier de Bayard, who would one day be known as the last true knight.

The Chivalric Code of Chevalier de Bayard

Pierre Terrail, known to posterity as Chevalier de Bayard, was not merely a knight by title but also the living embodiment of chivalric virtues. The investiture he received on the battlefield was more than a mere accolade; it was a sacred bond to the chivalric code that governed his every action. His life was a testament to honor, loyalty, and knightly charity principles. A staunch defender of those scorned by society, Bayard was known for his efforts to aid the recovery of prostitutes and assist those stricken by plague.

He shone as a beacon of compassion in an era often dimmed by the shadows of cruelty and injustice. Unlike many of his contemporaries who succumbed to the brutalities of war, Bayard maintained a steadfast respect for the weak and the defeated, often tempering the harshness of military necessity with a rare and genuine sense of justice, even paying from his coffers for provisions that others would seize by force.

Bayard’s leadership on the battlefield was marked by a protective streak that extended beyond his immediate company. He was often seen leading the charge, yet he played the guardian in retreat, ordering his men to douse the flames set by less scrupulous soldiers and stationing sentinels to safeguard churches and monasteries. Under his command, places of worship and their helpless seekers of sanctuary were shielded from the ravages of war. Such was the Chevalier de Bayard’s reputation for kindness that Italian villagers, typically driven to hide at the approach of armed men, would instead welcome his troops with open arms, showering the “good knight” with acclaim and offerings.

This celebrated kindness did not diminish Bayard’s prowess in combat; he was as fierce and formidable a warrior as any. His mercy did not extend to his enemies on the battlefield, yet this ferocity was not at odds with his deep religious conviction. Bayard saw his role as a knight as a divine calling, entering each fray with a prayer, entrusting his fate to the will of God. He embodied the fearless knight, a figure whose faith was as unyielding as his sword arm.

Chevalier de Bayard’s Infamous Duel During the Italian Wars of 1499–1504

The Italian Wars of 1499–1504, a series of conflicts that engulfed the Italian peninsula, were born out of the ambitions of the European powers to assert dominance over Italy’s rich and fragmented lands. The initial war of 1494–1498 had been ignited by Ludovico Sforza of Milan, who beckoned Charles VIII of France to claim Naples, thus setting a precedent for foreign intervention in Italian affairs. In this backdrop of strife and shifting alliances, Pierre Terrail, the Chevalier de Bayard, would carve his name into the fabric of military legend.

The Chevalier de Bayard’s rise to fame in Italy was punctuated by an episode in 1502 that exemplified his deep adherence to the chivalric code. When the Gascon soldier Gaspar detained the Spanish knight Don Alonzo de Soto-Maior, Bayard intervened to ensure the noble prisoner was spared ill-treatment. Welcoming Sotomayor into his household, Bayard extended the utmost courtesy and respect to his captive. Yet, upon release, Sotomayor cast aspersions on Bayard’s honor, falsely accusing him of cruelty. Incensed by such baseless claims, Bayard, who was still convalescing from bouts of malaria, issued a challenge of a duel to the death, dismissing the right to be represented by another despite his weakened state.

On the day of the duel, Bayard, having just recovered from a fever, laid prostrate on the earth, offering his soul to God, then rose to meet his adversary. Sotomayor, seeking to exploit Bayard’s frailty, delayed his arrival, forcing Bayard to endure the sweltering heat in full armor. When La Palice, a fellow French knight, pressed the Spaniard to commence the duel, Soto-Maior imposed a condition: the contest was to be fought on foot with sword and dagger, a stipulation designed to leverage his towering stature and robust build. Contrary to the expectations of many, Bayard accepted the terms without hesitation, dismounting with the determination to defend his tarnished honor.

The duel was a tense display of tactical feints and physical endurance. Soto-Maior repeatedly attempted to exhaust Bayard with heavy, overhand blows. But the Chevalier de Bayard, with agile grace, evaded each strike. Seizing an opportune moment, Bayard lunged, piercing the Spaniard’s throat with his sword and delivering the coup de grâce with a dagger to the eye. While French onlookers erupted into triumphant fanfare, Bayard, ever the paragon of chivalry, commanded silence, refusing to revel in the death of an adversary. He retreated to a church, humbly praying for the soul of the fallen Sotomayor, embodying the complex duality of a knight: a fearsome warrior in battle and a compassionate Christian in repose.

Centuries have passed since Bayard’s last charge, but his legacy endures in the annals of history as “the knight without fear and beyond reproach.” Yet, it was the moniker “le bon chevalier,” given for his warmth and kindness, that he treasured most—a name that spoke to the heart of a man who, amidst the turmoil of war, never lost sight of the tenets of chivalry and the virtue of goodness.

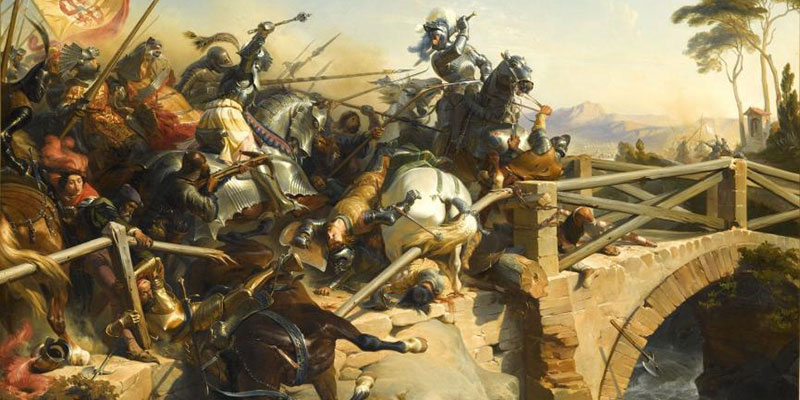

Chevalier de Bayard’s Stand at Garigliano

In the tapestry of military engagements that composed the Italian Wars, the Battle of Garigliano in 1503 stands out as a testament to individual valor epitomized by Pierre Terrail. His journey to this confrontation was marked by hardship; in 1502, Bayard had already been wounded at the Battle of Canossa, yet this injury would only underscore his resilience and unwavering courage. As the French army, pursuing claims to Naples, advanced towards the swollen waters of the Garigliano River, they found themselves facing the seasoned Spanish troops of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, a general whose tactical prowess had already cost the French dearly near Cerignola.

The French, determined to secure their position, constructed a bridge of boats under the shield of their artillery. This allowed them to establish a foothold, though the decision to delay further advances until spring led to the dispersal of their forces, a strategic error that the Spaniards, advised by Bartolomeo d’Alviano, would exploit with cunning precision. Utilizing the winter mists to mask their movements, the Spanish troops launched a surprise assault across the river, overwhelming the unprepared and divided French battalions. In the ensuing chaos, the French army faced a catastrophic defeat, their ranks shattered by the relentless pressure of the combined Italian and Spanish cavalry.

Amidst this desperate fray, Chevalier de Bayard’s chivalric spirit shone brightest. Gripping sword and spear, he took his stand on the bridge, facing down the advancing horde of enemies. His courage was such that even the 300 to 400 Spanish soldiers pressing forward could not force him to yield. Despite the hail of arrows and spears, Bayard held his ground, repelling every assailant who dared challenge his position. It was only through the intervention of his comrade Bellabre that Bayard was finally pulled from the bridge to safety. His heroic stand provided the critical time needed for the French to regroup and mount their artillery, setting the stage for a counterattack.

The legend of Bayard’s stand at the Garigliano would ripple through the annals of history, elevating his reputation to mythical proportions. Even Pope Julius II, recognizing the knight’s extraordinary prowess, attempted to enlist Bayard’s service. However, despite Bayard’s unmatched bravery, the French suffered a grievous loss; the battle nearly decimated their forces. The remnants of Louis XII’s army found themselves besieged in Gaeta, ultimately negotiating terms that would see the release of prisoners and a safe passage northward, a small mercy granted by a magnanimous Fernández de Córdoba.

The Italian Wars, which had seen the French capture of Milan in 1499 and the initial incursions into Naples, would culminate in 1504 with the expulsion of French forces by Ferdinand of Aragon. This ebb and flow of territorial control underscored the period’s volatility and the complexity of Renaissance warfare. Through it all, Chevalier de Bayard’s legacy as the last true knight would endure, a beacon of chivalric virtue amidst the shifting sands of allegiance and the brutal necessities of war.

In the Service of King Louis XII: Quelling Rebellion & the Beginning of the War of the League of Cambrai

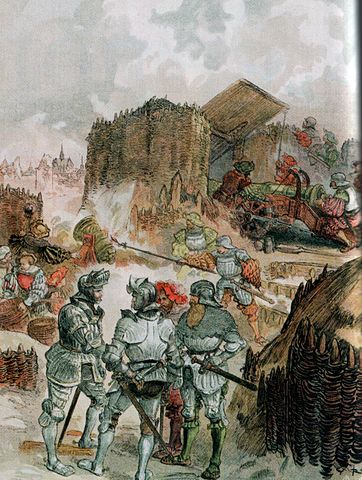

In the service of King Louis XII, Chevalier de Bayard’s chivalric deeds continued to resonate throughout France and beyond. 1508 marked a significant chapter in Bayard’s illustrious military career during the Siege of Genoa. As Louis XII sought to quell the rebellion that had taken hold of the city, Bayard emerged as the embodiment of martial prowess and knightly valor. At the helm of a daring cavalry charge, Bayard and the French gendarmes faced a formidable Genoese militia, their pikes forming a defensive phalanx upon a steep mountain slope.

Against staggering odds, the chevalier’s indomitable spirit broke through the barricades, sending the Genoese ranks into a retreat. His triumph was not merely a strategic victory but a moment of legendary bravery that would see him enter the subdued city in the glow of triumph, riding in the wake of a king he served with unwavering fidelity.

Bayard’s renown as a knight par excellence was further solidified in the summer festivities of that year when King Louis XII played gracious host to King Ferdinand of Spain. Amidst the splendor of tourneys, feasts, and dances, the Chevalier de Bayard shone as the unrivaled champion, a reminder of his prowess at the Garigliano, where he had previously faced the formidable Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, now present as an honored guest. In the courts as on the fields of battle, Bayard was the exemplar of chivalry and skill, his legacy further enriched by the bonds of respect forged even with former adversaries.

The following year, 1509, saw the formation of the League of Cambrai, an alliance of European powers against Venice, aiming to curtail its dominion in northeastern Italy. King Louis XII, recognizing Bayard’s exceptional qualities, entrusted him with raising a company of horse and foot soldiers. Until then, the French infantry had been regarded with contempt, but under Bayard’s leadership, this new force became a paragon of discipline, morale, and combat efficiency.

This company would play a pivotal role during the Battle of Agnadello against Venetian forces. On the 14th of May, 1509, when the French vanguard found itself in jeopardy, Bayard’s men intervened with decisive action, rescuing their compatriots from the brink of defeat and contributing to a significant French victory.

The campaign against Venice further highlighted the Chevalier de Bayard’s capabilities as a fearless warrior and a leader capable of inspiring and transforming his troops. His company’s performance at Agnadello served as a beacon of military reformation, demonstrating that even the most undervalued soldiers could achieve greatness with exemplary leadership. In every respect, Bayard upheld the virtues of chivalry and honor, crafting a legacy that would endure long after the dust of those battles had settled.

Bayard’s Prowess in the Siege of Padua and the Dissolution of the League of Cambrai

In the latter part of 1509, the Siege of Padua proved to be another arena where Pierre Terrail, the Chevalier de Bayard, distinguished himself amid the chaos of warfare. Under the command of Jacques de La Palice, French forces, including Bayard, united with their German allies led by Emperor Maximilian I.

Despite the siege’s eventual failure, the early advancements and tactical achievements could largely be attributed to Bayard’s exceptional blend of strategic insight and fearless courage. His ability to remain composed under pressure while simultaneously leading charges with audacious courage underscored his reputation as a military commander of unparalleled caliber.

With the withdrawal of the emperor’s forces from Padua, Bayard retreated to Verona, where he led 300 men-at-arms with a finesse that demonstrated his mastery over the subtler arts of warfare. During this period, the Chevalier de Bayard’s engagements went beyond conventional battles; he excelled in guerilla tactics, executing raids and ambushes that rattled the Venetian adversaries. His forays into what would now be considered special operations showcased a versatile leader adept at adapting to the changing dynamics of Renaissance warfare.

The shifting allegiances of the Italian Wars brought Bayard to Ferrara in 1510, now aligned with the Duchy of Ferrara, which had joined the fray as part of the League of Cambrai. While sharing command of the French forces stationed there, Bayard’s conduct and bravery impressed Duke Alphonso d’Este and his illustrious wife, Lucrezia Borgia. His biographer, “The Loyal Servant,” paints a picture of mutual respect and admiration between Bayard and Lucrezia, with Bayard regarding her as a paragon among women. His visits to Ferrara, including one with Gaston de Foix, would precede the tragic Battle of Ravenna, further intertwining Bayard’s story with the fateful narrative of the Italian Wars.

By 1511, the political landscape had transformed dramatically with the collapse of the League of Cambrai, spurred by Pope Julius II’s apprehension over France’s expanding influence in Italy. The ensuing Holy League pitted France against a coalition of powers, including former allies. Despite the reversal of alliances, Bayard’s military endeavors continued with the same vigor and effectiveness. In skirmishes near Ferrara, his skills as a commander and a knight earned him further acclaim, at one point nearly leading to the capture of Pope Julius II himself.

Amid the conflict, Bayard and Duke Alphonso found themselves excommunicated, a spiritual censure that added another layer of complexity to Bayard’s role in the wars. The duration and impact of this excommunication on Bayard remain a subject of historical curiosity. Yet, throughout the tumult of shifting alliances and ecclesiastical condemnation, Bayard’s chivalric spirit remained unblemished, his actions continually reflecting the honor and courage that had become synonymous with his name.

The Waning Campaigns of Chevalier de Bayard in the Service of King Louis XII

As the Italian Wars trudged, 1512 proved an arduous year for Pierre Terrail, the venerable Chevalier de Bayard. His undiminished leadership was on full display at the Siege of Brescia, where he led a determined charge against the city’s fortifications. At the forefront of the fray, Bayard embodied the knightly ideal, pressing the assault even as the French forces were repulsed repeatedly.

In the fierce struggle, Bayard sustained a grievous wound to his thigh. Despite his injury, his efforts were pivotal in breaching the defenses, allowing the French troops to pour into the city. His chivalry was further manifest when he safeguarded a noblewoman and her daughters from harm. As he convalesced, tended to by the ladies who serenaded him, news of the impending battle at Ravenna spurred his departure. In a gesture of magnanimous generosity, Bayard bequeathed a substantial gift to the young women who had cared for him, leaving behind a legacy of kindness amidst the ravages of war.

Bayard, still recovering, hastened to join his commander and comrade, Gaston of Foix, Duke of Nemours, at the Battle of Ravenna in 1512. The French cavalry, bolstered by Bayard’s presence, tipped the balance of the encounter in France’s favor. Yet, victory came at a devastating cost as the Duke fell in combat, plunging Bayard into mourning and transforming a tactical victory into a strategic defeat for France. The loss of de Foix was not merely a blow to French aspirations in Italy but a profound personal sorrow for Bayard, who had seen a kindred spirit of chivalry and martial prowess in his commander.

Later that year, Bayard’s relentless campaign continued as he ventured to Navarre with La Palice. Their mission was to aid John III and his queen, Catherine, in reclaiming their kingdom from Spanish control. Bayard’s martial excellence shone through once more during the capture of Tiebas, but the fortunes of war were erratic, and the subsequent assault on Pamplona on November 27, 1512, met with failure.

The subsequent year, the Chevalier de Bayard was embroiled in the Battle of the Spurs in 1513, where Henry VIII’s forces bested the French. In a scene reminiscent of his earlier encounters, Bayard sought to rally his compatriots but found himself cornered. True to his code, he refused to yield, instead capturing an English officer through a daring gambit and then paradoxically surrendering to his captive.

King Henry VIII, much like Ludovico Sforza before him, was so taken with Bayard’s prowess that he released him without ransom, extracting only a promise of a brief respite from combat- it is believed this would be for six weeks. In these final campaigns under King Louis XII, Bayard continued to display the virtues that had made him the epitome of knighthood, a figure of martial nobility in an era that increasingly relegated such ideals to the pages of romance.

The Battle of Marignano: Victory and the Honor of Knighting a King

The Battle of Marignano, the last significant engagement of the War of the League of Cambrai, stands as one of the most storied moments in the annals of military history and as the crowning achievement of Pierre Terrail, the Chevalier de Bayard. With the ascension of Francis I in 1515, Bayard found his esteemed position as lieutenant-general of Dauphiné quickly eclipsed by the pressing needs of war. Drawn into the fray for control of the Milanese territory, Bayard accompanied the young king into the teeth of a formidable Swiss army. The ensuing conflict would see the French forces triumph, a victory owed in no small part to the martial excellence of Bayard, the courageous leadership of King Francis, and the indomitable French gendarmes.

Audacious feats marked the French campaign, none more so than the surprise capture of Prospero Colonna, the Papal commander, at Villafranca. The raid, spearheaded by Jacques de la Palice and fueled by Bayard’s expert guidance, was a masterstroke of cavalry warfare, yielding a high-ranking prisoner and a treasure trove of spoils. In the grueling combat of Marignano, the Swiss forces initially surged forward with such ferocity that they drove back the landsknecht defenders and seized some of the French artillery. However, the thunderous charge of Bourbon’s cavalry, with Bayard in the vanguard, blunted the Swiss offensive despite the cavalry enduring heavy casualties.

As dusk descended and the moon glowed on the chaotic battlefield, the din of clashing arms continued unabated. Undeterred by the shroud of night, King Francis and Bayard led frenetic cavalry charges that consistently repelled the Swiss advancements. The ferocity of the night’s engagements claimed the lives of several French nobles, including the valiant Prince of Tallemont. Bayard’s dauntless sword arm carved a path through the Swiss ranks to rescue the beleaguered Duke of Lorraine, highlighting his unwavering bravery even amidst the most perilous circumstances.

With the dawn came renewed combat. The French grand battery, reassembled and resolute, awaited the Swiss, whose numbers had been thinned by desertion that night. As the Swiss phalanx advanced, the artillery’s roaring volleys decimated their ranks, yet still, they pressed on with an ironclad resolve that would have broken lesser foes. The landsknechts faltered again under the Swiss onslaught. Still, the determined charge led by Bayard finally stemmed the tide, preserving the French position and contributing to the ultimate victory.

In the aftermath of the battle, Francis I, elated by the triumph and profoundly aware of the historic moment, sought to be knighted in the field by the most chivalrous figure of the age. Bayard, the knight without fear and beyond reproach, had the honor of dubbing the king a knight, further solidifying his status as the paragon of knightly virtue. The Battle of Marignano was not just a military victory for France but also the pinnacle of the Chevalier de Bayard’s storied career, a testament to his skill, bravery, and unwavering commitment to the chivalric code.

The Siege of Mézières: Shielding France from invasion

The Italian War of 1521–1526, a resurgence of hostilities between Francis I of France and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, would provide the stage for one of Chevalier de Bayard’s most legendary exploits. As the drums of war beat once again, Bayard, leading a mere 1,000 men, was tasked with defending Mézières, a fortress town deemed indefensible by many. Yet, against an imperial army numbering 35,000, Bayard orchestrated a tenacious defense so inspired that after six arduous weeks, the imperial generals were compelled to abandon the siege. His resolute defiance at Mézières became a bulwark that shielded the heartland of France from the looming threat of invasion, buying precious time for King Francis I, who lacked the forces to repel the might of the Holy Roman Empire.

Bayard’s stand at Mézières became the stuff of national acclaim; all of France hailed him as the nation’s savior. His feat was a military victory and a stirring symbol of indomitable spirit and patriotism. As a grateful nation rejoiced, Francis I, sought to honor the knight who had bravely forestalled disaster. The Chevalier de Bayard was inducted as a knight of the prestigious Order of Saint Michael and was granted command of 100 gens d’armes in the king’s name, an accolade typically bestowed only upon princes of the blood. Such an honor reflected the high esteem in which Bayard was held and the magnitude of his service to France.

The Siege of Mézières stood as a testament to the strategic understanding and unwavering courage that defined Bayard’s career. His successful defense did not merely repel an invading force but ensured the integrity of France at a critical juncture. Bayard’s ability to rally his outnumbered troops and hold fast against overwhelming odds was instrumental in preventing the imperial forces from penetrating deeper into French territory. The significance of Mézières lay not only in its military reprieve but also in the morale boost it offered to a nation under siege. It was a moment that exemplified the highest ideals of chivalry and gallantry, virtues that Bayard embodied throughout his life.

In the wake of the siege, Chevalier de Bayard’s name was enshrined in the annals of French heroism. His leadership at Mézières would be remembered as one of the most daring episodes of resistance during the Italian Wars. It was a chapter that reinforced the Chevalier’s reputation as a peerless knight, one whose deeds transcended the mere confines of battle to become a beacon of hope and an emblem of the enduring spirit of France.

The Final Deed and Enduring Legacy of Chevalier de Bayard

In 1524, after quelling an uprising in Genoa and dedicating himself to curbing a plague in Dauphiné, Pierre Terrail, Chevalier de Bayard, was once again called upon to serve in the fields of Italy. He joined forces with Admiral Bonnivet, but misfortune struck at Robeco, where the French faced defeat, and Bonnivet himself was injured. In this dire hour, Bonnivet beseeched Bayard to take command and salvage the remnants of their army. True to form, Bayard mounted a formidable rear guard, his strategic acumen and bravery shining through as he repelled the enemy’s vanguard. Yet fate delivered its cruel blow at the river Sesia; while ensuring the safety of his men during the retreat, Bayard was struck down by an arquebus ball, his life ebbing away on the battlefield on April 30, 1524.

As he lay dying, surrounded by foes, Bayard was attended by two figures from his past: Pescara, the Spanish commander, and Charles, Duc de Bourbon, who had once fought alongside Bayard but now served the opposing side. There, Bourbon uttered his mournful words, recognizing the virtue of the fallen knight. Bayard replied, “Sir, there is no need to pity me. I die as a man of honour ought, doing my duty; but I pity you, because you are fighting against your king, your country, and your oath.”

Steadfast even in death, the Chevalier de Bayard affirmed his honor and subtly admonished Bourbon’s breach of fealty to France. His body, treated with respect by those who had been his adversaries, was eventually returned to his compatriots and laid to rest in the soil of his homeland and was first interred at Saint-Martin-d’Hères, with his final interment at the Collegiate Church of Saint-André in Grenoble in 1822.

Bayard’s death was a loss that resonated far beyond the immediate grief of his comrades-in-arms. As news of his passing spread, reactions poured in from nobility and commoners alike, for Bayard had been a figure who transcended the standard divisions of society. He was eulogized as a peerless soldier, celebrated for his tactical brilliance and the meticulousness of his military intelligence, and as a man of profound chivalry whose personal virtues mirrored the highest ideals of the age.

Tributes to the Chevalier de Bayard extolled his mastery of reconnaissance and espionage, his ability to divine the enemy’s movements with uncanny accuracy, and his conduct that never strayed from the highest standards of knightly honor. His legacy endured as a touchstone for military leaders and a paragon of chivalric virtue for all who aspired to live by the code of the true knight. The “knight without fear and beyond reproach” became an enduring emblem of valor and honor, his story a source of inspiration for generations to come, and his name a byword for chivalry’s very essence.