20 Elite and Extraordinary Regiments of the Continental Army

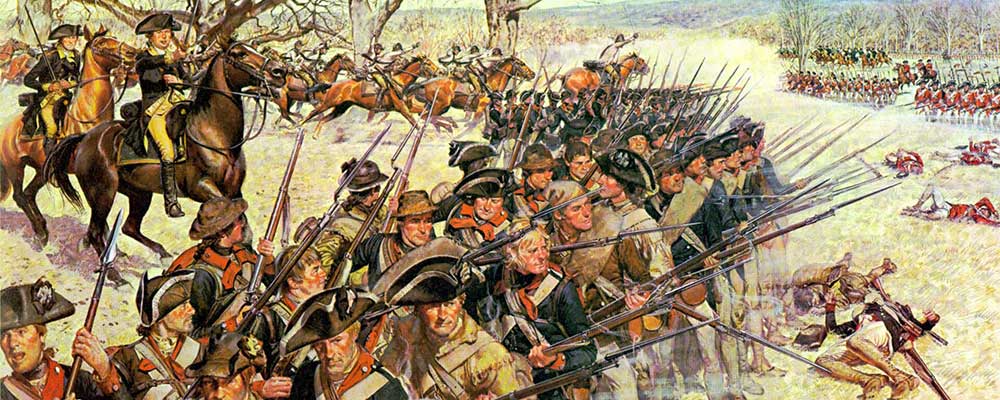

The Continental Army started as a ragtag collection of farmers, craftsmen and frontiersmen fighting for freedom. But out of these desperate beginnings, great things were created: groups of soldiers more skilled and extraordinary than the world had ever known. From Trenton to Yorktown, these elite regiments of the Continental Army carried the Revolution on their backs. During the darkest days of the war, General George Washington often called upon these men, for their skill, discipline, endurance, and bravery often made the difference between defeat and victory.

These remarkable regiments include such groups as Glover’s Marblehead Mariners, who fought at sea as well as on land, and Morgan’s Riflemen and the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, who challenged not only the British but also the world of warfare and society around them. In total, these 20 regiments tell the amazing story of how Washington and his army learned to fight, adapt, and endure against impossible odds.

Glover’s Marblehead Regiment (14th Continental Army Regiment)

Battles: Siege of Boston (1775–1776), Battle of Long Island (1776), Battle of Pell’s Point (1776), Battle of White Plains (1776), Crossing of the Delaware and Battle of Trenton (1776), Battle of Princeton (1777)

Colonel John Glover’s regiment was assembled in Marblehead, Massachusetts, out of a tough and experienced band of fishermen, sailors, and traders. They were unrivaled in discipline, seamanship, and esprit de corps by any other unit in the Continental Army; the kind of devotion and teamwork that takes root on the Atlantic in peacetime, not during war. The 14th Continental Regiment (the Marbleheaders’ official name) made their first mark on the Revolutionary War in the Siege of Boston, when Glover’s men ferried supplies, men, and artillery across the harbor under the British guns. When George Washington needed a resourceful and dependable regiment, he knew just who to call.

August 1776, after the New York rout at Long Island, Washington’s army was encircled by the British and desperate to escape. During one of the Revolutionary War’s great miracles, Glover’s regiment silently rowed 9,000 men, horses, and cannon across the East River under the cover of fog. Six months later on Christmas night, they did it again, piloting the army across the icy Delaware for the surprise attack on Trenton. Without Glover’s men, there would have been no escape and the Revolution might have ended that winter.

The Marbleheaders also showed valor and fighting spirit in the Battle of Pell’s Point, at White Plains, and Princeton, often serving as Washington’s last defense and rear guard. Few other regiments could match the Marbleheaders’ amphibious prowess and unity. Glover’s regiment was also ethnically diverse for the time, comprising fishermen and farmers, white and black men (many of whom were freed slaves), and even Native Americans. Their unity and discipline were a model for other units. The men of Marblehead showed that the seamen and fishermen of the town, and the rest of the country, could and would become the soldiers they needed to be. In so doing, they became the regiment that saved the Revolution.

Green Mountain Boys (Vermont Militia / Continental Service)

Battles: Capture of Fort Ticonderoga (1775), Battle of Hubbardton (1777), Saratoga Campaign (1777)

The Green Mountain Boys were a militia organized from frontiersmen who were inhabitants of the New Hampshire Grants, later Vermont. They were the first to take up arms not against the British, but against the claims of New York to the territory. The unconventional Ethan Allen led them and came to symbolize the hardy, freewheeling character of the frontier. At the outbreak of the war in 1775, Allen saw his opportunity to deal a blow for the colonies. On the morning of 10 May 1775, he led a successful surprise attack on Fort Ticonderoga, one of the first significant victories of the war, for which the Americans captured valuable artillery for the Continental Army.

Allen was captured while leading a botched assault on Montreal, and command of the regiment passed to Seth Warner. The Green Mountain Boys continued to make a name for themselves as brave and tenacious fighters. In 1777, the regiment fought a well-executed rear-guard action at the Battle of Hubbardton after most of the American force was retreating from Fort Ticonderoga. In 1777, the regiment also fought in the Battle of Saratoga, a major turning point in the war in which the Americans scored a great victory, enabling them to secure French support.

The Green Mountain Boys later played a role in Vermont’s successful push for statehood, which was heavily based on the same ideals they fought for in the war. The regiment had a reputation for discipline, marksmanship, and courage, and they became a symbol of the fierce, stubborn character of the northern frontier, as well as of how a small group of men could influence a continent.

Pulaski’s Legion

Battles: Battle of Brandywine (1777), Battle of Germantown (1777), Siege of Charleston (1779), Siege of Savannah (1779)

Led by the Polish nobleman and military leader Count Casimir Pulaski, Pulaski’s Legion was among the most unique and well-drilled units to serve under the Continental banner. A mounted infantry unit consisting of cavalry and light infantry, Pulaski’s Legion was trained in European cavalry tactics while also able to adapt to the needs of its new homeland. Pulaski was a renowned cavalry leader before the war, having fought against Russian forces in Poland and was known as the “Father of the American Cavalry.”

The Legion was initially formed in 1778 to fight against British and Loyalist cavalry operating along the southern frontier. General George Washington considered Pulaski to be an embodiment of military professionalism and fearlessness. Pulaski’s Legion first saw action during the Siege of Charleston in 1779. Pulaski and his Legionnaires charged British cannons in an attempt to aid the Americans’ defense of the city. The Legion was noted for its ability to move quickly and with purpose, and they delivered sharpshooters with devastating accuracy.

The Legion would meet its greatest test during the Siege of Savannah in 1779. Pulaski rode his horse into battle and attempted to lead a cavalry charge against entrenched British soldiers. Pulaski was struck by grapeshot and would die from his injuries days later. Pulaski was seen as a martyr to the causes of Poland and America.

The Legion was short-lived as a regiment but would have a significant influence over the development of future American cavalry units. Its members would go on to train future American mounted units in the discipline and tactics that Pulaski would have instilled. Pulaski, along with Marquis de Lafayette and Thaddeus Kosciuszko, is one of only a few foreign-born officers to be granted honorary citizenship by the United States.

Moses Hazen’s Regiment (The Canadian Regiment)

Battles: Siege of Quebec (1775–1776), Battle of Staten Island (1777), Battle of Brandywine (1777), Battle of Germantown (1777), Battle of Yorktown (1781)

The Canadian Regiment, led by the former British officer Colonel Moses Hazen, was a one-of-a-kind formation in the Continental Army. It was raised in 1776 by men of different nationalities, including French Canadians, Acadians, New Englanders, and Indians. This diverse unit served as a testament to the international character of the Revolutionary War. It was also known as “Hazen’s Regiment” or “Congress’s Own,” as it was raised directly under the authority of the Continental Congress rather than through a state legislature, allowing it a great deal of autonomy and freedom from state control.

The Regiment’s first major action occurred during the disastrous American invasion of Canada, where they participated in the Siege of Quebec in some of the most unforgiving winter conditions imaginable. After the retreat from Canada, the regiment regrouped and went on to fight at Staten Island, Brandywine, and Germantown to name but a few.

The unit was noted for its discipline and flexibility, and Hazen’s leadership kept the regiment united through long forced marches, brutal winters, and the often nonexistent pay situation. The unit’s bilingual nature and knowledge of both frontier and European-style warfare made them ideal for reconnaissance and skirmishing. By 1778, the regiment had developed a reputation as one of the most dependable and professional forces in the Continental Army.

The regiment’s defining moment came in 1781 at the Siege of Yorktown when Hazen’s Regiment was a part of the final assault that resulted in the surrender of British General Cornwallis. This endurance from the freezing fields of Quebec to the victory at Yorktown would come to symbolize the perseverance and diversity of the patriot cause. Hazen’s Regiment demonstrated that loyalty to the ideals of liberty, not birthplace or language, could unite people from across North America into one exceptional fighting force, much like the emerging identity of America itself.

1st Maryland Regiment (“The Maryland Line”)

Battles: Battle of Long Island (1776), Battle of Harlem Heights (1776), Battle of Camden (1780), Battle of Cowpens (1781), Battle of Guilford Courthouse (1781)

Raised in 1776, the 1st Maryland Regiment would be known throughout the war and to this day as “The Maryland Line.” The soldiers in this regiment were in many ways the best the Continental Army had to offer. They were men who answered their state’s call to form a regiment to help fight for independence, and their time together in the service forged them into a professional and disciplined fighting force. “The Maryland Line” earned their nickname on the fields of the Revolution through repeated acts of steadfast courage and undying discipline.

At the Battle of Long Island, American General George Washington’s entire army was in great danger of being encircled and destroyed. As the remnants of the army fled south from Brooklyn Heights, the Maryland regiment formed the rear guard, repelling repeated British attacks through the consistent use of their bayonets. The Regiment suffered near total casualties as they repeatedly charged, and their sacrifice allowed thousands of Americans to retreat. General Washington was moved to say, “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose!”

After the battle, the Marylanders would go on to fight in campaigns in both the north and south. In the north they would fight at Harlem Heights, Trenton, and Princeton. Eventually, they were sent south and fought in many of the Carolina campaigns, with bravery and discipline the Americans desperately needed at this point in the war. At the Battle of Camden, despite suffering massive casualties, the 1st Maryland Regiment refused to break formation in the face of British attack. This defeat was later avenged at Cowpens and Guilford Court House.

The Maryland line’s professional discipline was the backbone of American victory at these battles. The green and red-coated, consistent volley fire of “The Old Line” would help to put a halt to the British momentum in the South and give the Continental Army time to build strength.

The regiment’s nickname of “The Old Line” was based on their reputation as the most reliable fighting force in the Continental Army. Maryland even adopted “The Old Line State” as the official nickname of the state in honor of this regiment. The 1st Maryland Regiment was made up of men from all walks of life. Farmers, craftsmen, and men from all over the state signed up to serve in this unit and fight for independence. The regiment contained all of the Continental Army’s best qualities: courage, discipline, and honor. From the desperate flight from Long Island to the eventual victory, the steadfast line of “The Maryland Line” held fast when America needed it most.

Morgan’s Riflemen (Virginia Rifle Regiment)

Battles: Siege of Boston (1775), Battle of Quebec (1775), Battle of Saratoga (1777), Battle of Cowpens (1781)

Morgan’s Riflemen were a regiment of American sharpshooters who were amongst the most feared and effective soldiers of the Revolutionary War. Commanded by Daniel Morgan, a frontiersman and former surveyor from Virginia, the Riflemen were formed in 1775 and brought a new style of warfare to the conflict. Equipped with long-barreled Pennsylvania rifles that could hit a target at over 250 yards, Morgan’s men were expert woodsmen, hunters, and skilled at skirmishing and irregular tactics. Pioneers of American marksmanship, they gained a fearsome reputation for terrorizing British troops long before the main armies even engaged.

The Riflemen’s most significant contribution to the war effort came at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, where Morgan’s men played a decisive role in the American victory over General Burgoyne’s army. By picking off British officers and artillerymen with precise rifle fire, Morgan’s riflemen sowed confusion in the enemy’s ranks and helped to turn the tide of battle. The victory at Saratoga was one of the most decisive of the war, and helped to secure French intervention in the conflict. Later, in the southern campaign, Morgan and his Riflemen led a mixed force of rifle and militia troops to a brilliant victory at Cowpens in 1781, a battle often cited as a tactical masterpiece of military history.

In addition to their battlefield achievements, Morgan’s Riflemen were significant in transforming American warfare. They demonstrated that mobility, stealth, and marksmanship could overcome the traditional European style of fighting with fixed formations. The Riflemen’s tactics would also be a forerunner to the guerrilla warfare used in later conflicts. Under Daniel Morgan’s leadership, the marksmanship and military skill of Morgan’s Riflemen helped to transform the Continental Army from a ragtag band of amateurs into a force that could defeat the most powerful army in the world, one shot at a time.

1st Rhode Island Regiment (“The Black Regiment”)

Battles: Battle of Rhode Island (1778), Siege of Yorktown (1781)

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment was another remarkable unit that fought in the American Revolution and was known as “The Black Regiment”. It was first constituted in 1778, with Colonel Christopher Greene at the helm. It was an all-black militia regiment, and its soldiers were mainly recruited from free and enslaved African Americans who had been promised freedom in exchange for service in the Continental Army. Although the regiment faced racial prejudice and some officers’ doubts about their capability and commitment, they quickly demonstrated their discipline, valor, and determination to fight for their personal and national freedom.

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment’s most notable engagement was the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778. In this battle, the regiment, which was significantly outnumbered, was tasked with defending a strategic position against a British and Hessian attack. For several hours, the 1st Rhode Island bravely held their ground, repelling repeated assaults and enabling the rest of the Continental forces to retreat in an organized manner.

Their conduct during this battle earned them praise from both American and foreign officers, with a French observer remarking on their “coolness and bravery under fire”. The 1st Rhode Island also fought at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, where they played a part in the siege that forced the British General Cornwallis to surrender, marking the end of the Revolutionary War.

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment’s legacy as a symbol of equality and bravery in the face of great injustice remains strong. They stood alongside white soldiers and earned the respect of their fellow soldiers, challenging the racial norms of the 18th century and setting an example for future generations. Their courage on the battlefield not only helped secure American independence but also advanced the cause of freedom for all who are willing to fight for it.

Knowlton’s Rangers

Battles: Battle of Long Island (1776), Battle of Harlem Heights (1776)

Knowlton’s Rangers were one of the Continental Army’s first major organized intelligence/reconnaissance operations, making them the precursors of the modern concept of special forces. Created as a volunteer unit in August 1776, they were led by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Knowlton of Connecticut. Numbering around 120 well-chosen men, Knowlton’s Rangers were given orders to scout behind enemy lines and take intelligence information wherever they could find it.

In addition to fighting, their orders were to gather information from all the places the men found themselves and report it to Washington. This was at the time of the Continental Army’s struggle to survive on Manhattan Island against the British during the New York campaign. The Continental Army’s actions at the Battle of Harlem Heights on September 16, 1776, would become the turning point of the campaign, and a key moment for Knowlton’s Rangers.

After retreating from Long Island with the British in hot pursuit, General George Washington needed to put together a counterattack to reinvigorate his troops. The battle was on September 16, and as the British pursued the retreating Continental Army, Washington set up a defensive position and sent Knowlton’s Rangers to attack from the flanks, followed by a group of Virginians under Colonel John Leitch. Knowlton’s Rangers and Colonel Leitch’s Virginians were caught by the British, but with the Rangers’ lead, the Americans fought hard.

Despite the loss of their commanding officer, Thomas Knowlton, who was killed in action, and the many casualties the units suffered, the battle was one of the first “decisive” victories of the war. Washington had given the final order to charge into the action, and the British were caught off guard by the American fight, which eventually became successful. Washington was so impressed with the way his troops fought that he wrote, “Knowlton was a brave and gallant officer, and his death will be a severe loss to the army.”

Knowlton’s Rangers were not a long-lived unit, but helped create the concept of the spy as a necessary part of American warfare, from Nathan Hale, one of Knowlton’s own men, to the Army Rangers of today.

Lee’s Legion (Light Horse Harry Lee’s Corps)

Battles: Battle of Paulus Hook (1779), Battle of Guilford Courthouse (1781), Siege of Ninety Six (1781), Siege of Yorktown (1781)

Lee’s Legion, led by the daring and brilliant cavalry officer Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, was one of the most effective and feared fighting units in the Continental Army. Comprised of both cavalry and light infantry, the Legion was formed in 1778, providing a hybrid force capable of striking with speed and precision. This fluid, adaptable unit was ideally suited to the hit-and-run warfare of the southern campaign. Under Lee’s command, they harassed British supply lines, ambushed Loyalist outposts, and gathered vital intelligence. Lee, a master of maneuver and deception, leveraged their mobility and cunning to significant effect, becoming a constant thorn in the side of the British command, who never knew where the next attack would come from.

The Legion’s defining moment came in August 1779 when Lee led a daring nighttime raid on the British-held post at Paulus Hook, New Jersey. By stealth and surprise, his men overran the garrison, capturing over 150 enemy soldiers and withdrawing with minimal casualties. This stunning victory earned Lee a gold medal from Congress, one of only a handful awarded during the entire war. Later, in the southern campaign, Lee’s Legion fought alongside generals Nathanael Greene and Daniel Morgan in a series of brilliant maneuvers that kept the British on the run from the Carolinas all the way to Virginia.

At battles like Guilford Courthouse and Ninety Six, Lee’s men were indispensable, using their speed to exploit weaknesses and their discipline to hold firm when outnumbered. By the time of the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, Lee’s Legion had become one of Washington’s most trusted strike forces. Known for their green jackets —a nod to their light cavalry roots —they combined European tactical precision with the improvisational spirit of the American frontier. The legacy of Lee’s Legion lived on long after the Revolution, inspiring future generations of American cavalry and cementing their commander’s place in the pantheon of Revolutionary heroes.

Lauzun’s Legion (French Allied Regiment)

Battles: Battle of Gloucester (1781), Siege of Yorktown (1781)

Lauzun’s Legion was among the most flamboyant and cosmopolitan units of the French expeditionary force under General Rochambeau to fight alongside the Continental Army. A corps of French, German and Polish infantry and hussars renowned for their daring and dash, the unit was commanded by the Duc de Lauzun, Armand-Louis de Gontaut. Formed in 1778, it specialized in light cavalry tactics, reconnaissance, and raiding, making it a natural fit for Washington’s plans in the last years of the war.

One of its most celebrated moments was at Yorktown in 1781. As Washington and Rochambeau marched south from New York, Lauzun’s Legion screened the army’s movements and harassed British detachments en route, often clashing with Loyalist cavalry and foraging parties. At Gloucester, just across the river from Yorktown, Lauzun’s troopers tangled with British cavalry under the infamous Banastre Tarleton. In a fierce skirmish, the French riders drove Tarleton’s men from the field and secured the flank of the Allied army, dooming the British commander to death or surrender inside Yorktown.

The Legion was as famous for its panache as for its effectiveness. Lauzun’s Legion was a symbol of the international cooperation that was required for American victory. The cavalry uniform of Lauzun’s Legion —a bright blue jacket with gold trim —became a symbol of France’s commitment to the cause of liberty. Many of the veterans of the Legion fought in France’s own revolutionary wars after their return home, taking with them memories of America’s successful bid for independence. At Yorktown, they had fought shoulder to shoulder with Washington’s men and demonstrated that freedom’s cause could unite not only armies but also nations.

Left: Horsemen of the 16th Light Dragoons charge Continental infantry, while horsemen of the 1st and 2nd Continental Light Dragoons ride away firing their sidearms.

Center foreground: Captain William Wolfe of the 40th Regiment of Foot lies dead, while Lieutenant Hunter bandages his right hand.

Center background: Two Continental platoons fire on greenjackets, likely Ferguson’s Riflemen. A supply wagon is captured, and a Continental line fires from the woods to cover the main column’s retreat.

Right: British light infantry bayonet Continental soldiers by their camp huts.

2nd Continental Light Dragoons (Sheldon’s Horse)

Battles: Battle of Brandywine (1777), Battle of Germantown (1777), Battle of Monmouth (1778), Battle of Yorktown (1781)

The 2nd Continental Light Dragoons was authorized in December 1776 under Colonel Elisha Sheldon of Connecticut and grew into one of the most reliable and adaptable cavalry regiments in the Revolution. The unit, also known as Sheldon’s Horse, was among the most trusted and utilized throughout the war. Their duties frequently involved reconnaissance, communication, and patrols between Washington’s divided forces. They gained a reputation for discipline, speed, and effectiveness, becoming one of the most highly regarded units of the Continental Army.

The 2nd Dragoons were as known for their scouting and skirmishing ability as they were for their raiding and intelligence-gathering. This made them a great asset to Washington in the early campaigns of 1777 and 1778, when they operated in the mid-Atlantic colonies, skirmished with British patrols, and protected American supply lines. The regiment was recognized for its actions at Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth, and for its mobility and reconnaissance, which contributed significantly to Washington’s overall strategy.

In addition to conventional military duties, the regiment was involved in espionage and counterintelligence, including helping uncover Benedict Arnold’s treason and conducting surveillance in the Hudson Valley. The regiment’s use of light cavalry tactics —such as hit-and-run attacks, ambushes, and disruption of British supply lines —became a standard for American mounted troops.

By the war’s end, the 2nd Dragoons had become a true elite corps, fighting in the Yorktown campaign and putting constant pressure on the British positions in their final campaigns. The regiment is remembered for its blue uniforms trimmed with white and its exceptional discipline. They combined the traditions of European cavalry with the adaptability required by the American frontier. Sheldon’s Horse is the oldest continuously serving cavalry unit in U.S. history and is today recognized as the ceremonial forebear of the 1st Squadron, 2nd Cavalry Regiment.

1st Delaware Regiment (“Delaware Blues”)

Battles: Battle of Long Island (1776), Battle of Princeton (1777), Battle of Brandywine (1777), Battle of Camden (1780), Battle of Cowpens (1781), Siege of Yorktown (1781)

he 1st Delaware Regiment was one of the most professional, disciplined, and combat-tested units in the Continental Army. Known as the “Delaware Blues” because of their uniform color of blue with red facings, this unit was organized in early 1776 under the command of Colonel John Haslet. The regiment was among the first to earn Washington’s respect, who noted their military bearing and professionalism. During the Battle of Long Island, the regiment fought a rearguard action to hold the line long enough for the rest of the Continental Army to retreat to safety, and their actions on the battlefield made them one of the most respected regiments in the army.

The Delaware Blues would go on to fight in almost every significant engagement in the northern and southern theaters in the coming five years, at places like Princeton, Brandywine, and Germantown. The Delaware Regiment gained a reputation for discipline and staying power; it was said that once a Delaware regiment charged, nothing could stop it. George Washington was known to call the Delaware soldiers “the best soldiers in the army.” The regiment was nearly destroyed at the Battle of Camden in 1780. Still, the remnants were reorganized under new leadership and continued to fight in the South under Nathanael Greene in the battles of Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse.

The Delaware Regiment was down to a fraction of its original size by the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, but its fighting spirit remained as strong as ever. Having seen combat from the very beginning of the Revolution to its very end, the Delaware Blues represented the persistence and professionalism that made the Continental Army no longer just a militia but a true fighting force. The Delaware Regiment is known today as Washington’s most trusted infantry in both state and national military tradition.

Col. John Lamb’s Continental Artillery Regiment (2nd Continental Artillery)

Battles: Siege of Boston (1776), Battle of Long Island (1776), Battles of Trenton and Princeton (1776–1777), Battle of Monmouth (1778), and Siege of Yorktown (1781)

Colonel John Lamb’s 2nd Continental Artillery Regiment was among the most technically proficient and disciplined in Washington’s army. Comprised of New York artillery companies, Lamb’s regiment was raised in 1776 but had quickly built a reputation for marksmanship, organization, and engineering capabilities during Washington’s army’s many battles. Lamb, a veteran of the Sons of Liberty and one of the earliest firebrands of the revolution, had forged his men into a highly professional unit capable of executing the most complicated artillery tasks of the war, and supporting Washington’s army’s cannons had boomed from the first days of Boston to the vicious fighting in New York and New Jersey.

At Trenton and Princeton, Lamb’s gunners were integral in shattering the Continental Army’s surprise victories with pounding cannonades that pulverized British formations and raised American spirits. At Monmouth, their deadly accuracy and coordination in the oppressive heat helped to check superior British numbers. Lamb’s artillery was a symbol of the Continental Army’s growing technical acumen, a force that balanced European discipline with American innovation. With each campaign, the gunners’ skills were sharpened, and they were being prepared for the final test of their collective mettle.

That final test would be the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, and there Lamb’s regiment would unleash a pounding bombardment that would level British fortifications and drive Cornwallis to surrender. Washington himself reportedly complimented the regiment’s accuracy, as their fire systematically reduced enemy positions to rubble. The 2nd Continental Artillery’s showing at Yorktown was the pinnacle of professionalism that had been developing in the American ranks. Under the leadership of John Lamb, the 2nd Continental Artillery was a model of training, discipline, and capability—a unit whose cannon fire quite literally broke the last major stronghold of British power in America.

Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment (Thompson’s Rifle Battalion)

Battles: Siege of Boston (1775–1776), Battle of Quebec (1775), Battle of Long Island (1776), Battle of Trenton (1776)

The Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment, or Thompson’s Rifle Battalion, was one of the first light infantry units authorized by the Continental Congress. Raised in June 1775, it consisted of frontiersmen from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia who were armed with the Pennsylvania long rifle, capable of much greater range and accuracy than the British musket. Commanded by Colonel William Thompson, they made a name for themselves at the Siege of Boston for their ability to engage at long distances. They became a legendary force among both friend and foe.

They served in the invasion of Canada, taking part in Benedict Arnold’s expedition against Quebec in late 1775. Despite suffering heavy losses in the harsh Canadian winter, they demonstrated their value in skirmishes and scouting missions. The riflemen’s accuracy and ability to move quickly through rugged terrain were effective in guerrilla tactics. They had a notable impact on the development of similar light infantry tactics within the Continental Army. By 1776, the unit had been broken up and absorbed into other Continental regiments, with its veterans carrying their expertise with them.

The influence of the Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment extended well beyond its brief tenure as an independent unit. It established a new standard for marksmanship and frontier fighting, demonstrating the power of disciplined sharpshooters to influence the outcome of battles as significantly as traditional line infantry. American riflemen would continue to play a crucial role throughout the Revolutionary War, from the New Jersey campaign to the Battle of Saratoga, using the terrain to their advantage and honing the skills of stealth and deadly accuracy that would become a staple of American military tactics for years to come.

Whitcomb’s Rangers (Continental Rangers)

Battles: Battle of Hubbardton (1777), Saratoga Campaign (1777), raids along the Northern Frontier (1777–1779)

Whitcomb’s Rangers was raised in 1776 by Major Benjamin Whitcomb. A hardy veteran of Rogers’ Rangers and a native of New Hampshire, Whitcomb selected his men from experienced woodsmen, hunters, and trappers in the New Hampshire and Vermont areas, some of the most capable scouts and irregulars in the Continental Army. Stationed independently along the wild northern frontier, Whitcomb’s Rangers specialized in reconnaissance, intelligence, and ambushing British and Loyalist supply lines and detachments in the Canadian campaigns and the defense of the northern colonies against invasion. Whitcomb and his Rangers were well known for their mastery of the ways of the wilderness.

Whitcomb’s Rangers would go on to earn a reputation for their exploits during the Saratoga Campaign of 1777 as part of the American forces who harassed British supply lines and otherwise contributed to the defeat and surrender of General Burgoyne’s army. At one point, Whitcomb himself is credited with killing a British Brigadier General named Patrick Gordon in a skirmish near Ticonderoga. The Rangers’ reputation as a fearsome, hard-hitting, yet elusive fighting force made them the Continental Army’s eyes and ears in some of the war’s more remote and dangerous theaters.

As a fighting force that lived and fought on the edges of the “real war”, Whitcomb’s Rangers would become the personification of the colonial frontier fighter. Fighting not for glory or even for pay, but to defend their homes and to deny the British any advantage in the vast and lawless northern wilderness, the Rangers, though small in number, were an essential piece of the Revolution’s north front.

Their ethos and fighting spirit would be emulated by generations of American irregulars, from the Green Mountain Boys and the Allegheny Scouts to the rangers of future American wars. These men were to be found on the edges of the American experience, who lived and fought as only true men could.

Francis Marion’s Irregular South Carolina Militia (“Marion’s Men”)

Battles: Battle of Camden (1780), Battle of Eutaw Springs (1781), raids on Georgetown, Nelson’s Ferry, and Snow’s Island

Operating out of the South Carolina swamps was Francis Marion’s Irregular Militia, known simply as “Marion’s Men.” These were the guerrilla fighters who earned themselves the nickname “the terribles” by the British occupation in the southern colonies. After Charleston’s loss in 1780, Marion gathered a handful of volunteers who fought for the patriot cause in a war of attrition against British and Loyalist forces.

Marion’s Militia were farmers, hunters, and frontiersmen. They provided their own horses, weapons, food, and supplies. They were unpaid and often had very little time to rest between battles. Marion’s men attacked where the British least expected, moving in and out of the swamps and thick pine forests. They ambushed supply trains, destroyed supply depots, and carried out lightning raids, then melted back into the surrounding wilderness before reinforcements could be called.

Marion was a master of guerrilla tactics and personally led many of his attacks and raids. The men were small, flexible groups of troops who could make their own decisions. Marion’s most infamous enemy, British cavalry commander Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, is famously quoted as saying, “The Devil himself could not catch that old fox.” Tarleton’s colorful quote is how Marion got his most well-known nickname, The Swamp Fox. Marion’s unorthodox tactics of small, mobile forces that operated under the cover of familiar, dense terrain were ultimately a significant game changer, shifting the war in the South.

The Swamp Fox and his men were at the forefront of anti-British resistance in the southern colonies, frustrating the British occupation, stirring up patriot militias, and keeping the rebellion alive at its bleakest moments. His harassment of the British kept them on their toes, hindering their efforts and control of the countryside and forcing them to divert troops and resources away from the primary campaigns of the war, such as Cornwallis’s disastrous North Carolina campaign.

Francis Marion’s battles were seldom conventional field engagements, but his men fought in several skirmishes that helped lead to America’s eventual victory in the fight for independence. Marion’s men were auxiliary support for the American defeat of the British at Eutaw Springs and several other major battles. Their most significant victories, however, were the countless times they remained standing after the enemy had been chased away or had left. Their efforts of cunning, swift, and merciless hit-and-run strikes, surviving on meager resources and minimal supplies, are a model for later American guerrilla fighters.

Spencer’s Additional Continental Regiment (Connecticut)

Battles: Battle of Rhode Island (1778), Battle of Monmouth (1778), Sullivan Expedition (1779), and engagements in New Jersey and New York

Spencer’s Additional Continental Regiment was unique among the men of the Continental Army as one of the corps of so-called “Additional” units. These were independent line regiments created by the Continental Congress and distinct from the state troops that made up the vast majority of Washington’s Army. The regiment was organized in 1777 in Connecticut under the command of Colonel Oliver Spencer.

As “Additional” units, Spencer’s men were available for service anywhere in the Continental Army as a mobile strike force that could be deployed where Washington needed reinforcement most. The regiment drew veterans from the New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut lines, and was a highly regarded corps of professional soldiers.

The regiment saw service in several of the war’s most arduous campaigns, including the Battle of Monmouth, where it helped to staunch the American line, and the Battle of Rhode Island, where it supported General John Sullivan’s attempt to reclaim Newport from British occupation. The regiment also served in both line and skirmishing roles, making it one of Washington’s most adaptable corps. The men of Spencer’s Regiment were also present at the Sullivan Expedition of 1779 which saw a scorched-earth campaign through the Iroquois country of upstate New York designed to break the back of British Indian support for the British cause. By 1781, the regiment had been consolidated with others through attrition and organizational realignment.

The “Additional” units are regarded as the hard core of Washington’s Army and as an example of the growing professionalism of his force. Loyal directly to the Continental Congress, these units were not tied to a specific state and were available for service anywhere in the Continental Army.

Armand’s Legion (Armand’s Partisan Corps)

Battles: Battle of Monmouth (1778), Battle of Camden (1780), Battle of Yorktown (1781)

The regiment was one of the most international in the Continental Army, organized around a cadre of European volunteers. Armand’s Legion was recruited and officered mainly by French, German, and Polish volunteers who served in light cavalry roles modeled after Europe’s elite light horse. Armand served in the French Army before becoming a volunteer in Washington’s army in 1777 and raised much of the regiment himself at his own expense. In addition to proving his devotion to the cause, he demonstrated a taste for daring exploits.

Active in the middle and southern portions of the war, the Legion was in action at Monmouth in 1778, one of the largest, longest and bloodiest of the Revolution’s hottest days. They were also part of General Gates’s army at Camden in 1780, where Armand was wounded in the failed Southern campaign. Reorganizing his corps, he and his men continued to fight under the direct orders of General Washington until Yorktown (1781), where Armand’s cavalry was among the allied French and American horsemen that encircled Cornwallis’ army. Legion discipline and bold maneuvers were crucial in achieving the final victory.

Armand’s Legion was, in microcosm, the international aspect of the American Revolution. Small in numbers, but some of the most professional and battle-hardened in Washington’s army, Armand and his men were entirely devoted to the cause. The corps, at times known as “Armand’s Partisan Legion”, was one of the best and most effective in the Continental Army, truly representing international support for the American Revolution.

Virginia Continental Line

Battles: Battle of Great Bridge (1775), Battle of Brandywine (1777), Battle of Germantown (1777), Battle of Cowpens (1781), and Siege of Yorktown (1781)

The Virginia Continental Line was one of the most significant and longest-lasting elements of the Continental Army. It supplied manpower and leadership throughout the Revolutionary War. The Line developed from the first units raised in Virginia. It produced an extraordinary number of regiments that earned reputations for discipline and battlefield performance. The Line included elite units like Morgan’s Riflemen, known for marksmanship and tactics, as well as seasoned line troops that held their ground at Brandywine and Germantown. Virginia soldiers were often the mainstay of Washington’s army and fought in virtually every campaign from the beginning of the war to its victorious end.

In the Battle of Cowpens in 1781, Virginians under Daniel Morgan achieved one of the most stunningly planned and executed American victories of the war. It combined militia, riflemen, and Continental regulars in an envelopment that surrounded British forces. In the Siege of Yorktown later in 1781, Virginia regiments helped hold the American siege lines that Washington’s combined American and French troops used to force the surrender of General Cornwallis. These men had served for years, often under brutal conditions, and their perseverance became a measure of the Patriot cause.

The Virginia Line produced not only troops but also leaders, including Washington and generals Daniel Morgan, Peter Muhlenberg, and Edward Stevens. It reflected the professionalism that helped turn the Continental Army from a militia into a fighting force. Through its discipline, determination, and sacrifice, the Virginia Continental Line played a vital role in the fight for independence and became one of the most remarkable and battle-tested units of the American Revolution.

Pennsylvania Line (1st and 2nd Regiments)

Battles: Battle of Trenton (1776), Battle of Princeton (1777), Battle of Brandywine (1777), Battle of Germantown (1777), Battle of Monmouth (1778), and the Mutiny of 1781

The Pennsylvania Line consisted of the 1st and 2nd Pennsylvania Regiments and was one of the most experienced and professional in the army. The two units were among the first to be formed in the early days of the war and participated in nearly every major campaign under Washington’s direct command from Trenton to Monmouth. Their most notable early actions were Trenton and Princeton, where their reliability and precision in battle helped set the Continental Army on the road to recovery following the Delaware crossing. At Brandywine and Germantown, the Line once more demonstrated the increased effectiveness of the Continental Army against British attack.

Wintering at Valley Forge in 1777–1778, the men of the Pennsylvania Line would see some of the worst privations of the entire war. In the face of near-starvation, a lack of clothing and blankets, and the paltriness of their pay, they were transformed into battle-hardened veterans of the American cause under the discipline and training of Baron von Steuben.

By 1778, these regiments were among Washington’s most trusted and by 1783 had distinguished themselves again and again on the field, among their most notable actions being Monmouth, where, in the face of heat and bedlam, the men of the Line were able to maintain their hold on the field of battle. For their bravery and unit cohesion, they were considered by most officers to be instrumental in ensuring the survival of the Continental Army at its lowest points.

For all their battlefield distinction, however, it was away from the field of battle in January 1781, after years of stagnant pay and often missed wages, that the Pennsylvania Line would leave its indelible mark on the Continental Army. Mutinying at Morristown, New Jersey, the soldiers of the Line shocked Congress with a well-organized, nonviolent strike for their rights.

The rebellion of the Pennsylvania Line would lead to reforms in military pay and enlistment which had been long needed but long ignored. While most of the mutineers returned to the ranks and served with distinction to the end of the war after being given enough pay to satisfy their needs, the Pennsylvania Line’s reputation for battle and rebellion is still a large part of its legacy today.

North Carolina Light Infantry Corps

Battles: Battle of Camden (1780), Battle of Guilford Courthouse (1781), Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill (1781), and Eutaw Springs (1781)

The 6th Regiment, often referred to as the North Carolina Light Infantry Corps, demonstrated remarkable adaptability and resilience as a part of the Continental Army’s Southern campaign. Recruited from both experienced veterans and state militia, the regiment excelled in mobility, skirmishing, and irregular warfare, skills that proved indispensable in the harsh, guerrilla-style combat encountered in the Carolinas’ backcountry.

Under the leadership of Major General Nathanael Greene and other commanders, such as Thomas Sumter, these troops became a formidable, much-needed strike force. They relentlessly harassed British outposts, disrupted supply lines, and avoided decisive battles that could have left the Continental Army overwhelmed by British numerical superiority.

During the ill-fated Battle of Camden in 1780, many of North Carolina’s soldiers found themselves embroiled in the disastrous rout that befell the Continental Army. However, those who managed to escape the calamity went on to reorganize and improve their tactics. By the time of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in 1781, the expertise of the Light Infantry’s sharpshooters and their agile companies played a crucial role in inflicting significant casualties on Lord Cornwallis’s forces, even though it resulted in a strategic withdrawal. Their proficiency in engaging the enemy in small units, often over challenging terrain such as forests, swamps, and hills, provided a critical edge in the Southern conflict, where conventional European military strategies were often ineffective.

In subsequent confrontations, including the battles of Hobkirk’s Hill and Eutaw Springs, the North Carolina Light Infantry Corps continued to showcase its strategic value. By effectively merging guerrilla tactics with military precision, they launched relentless assaults that forced the British to retreat, often at a high cost. This contributed to the gradual erosion of royal authority in the Southern states.

Although these regiments are perhaps less renowned than their Northern counterparts, the North Carolina Light Infantry Corps exemplified the spirit of endurance, adaptability, and fierce independence that characterized the Revolutionary War. Their contributions were instrumental in setting the stage for the ultimate American triumph at Yorktown, solidifying their legacy as one of the Continental Army’s most extraordinary fighting units.

The Legacy of the Continental Regiments

The regiments of the Continental Army were far more than lines on a battlefield — they were the embodiment of a young nation’s resilience, creativity, and unity. From Glover’s seafaring Marbleheaders to Morgan’s deadly riflemen, from the courage of the Black Regiment to the precision of Lamb’s artillery, these units proved that determination and skill could overcome empire. Their leaders, often improvising in the face of scarcity, forged an army that grew from a collection of militias into a disciplined force capable of defeating one of the world’s most powerful military machines.

Their legacy extends beyond victory in the Revolution. The tactics, discipline, and spirit developed by these regiments laid the foundation for America’s future armed forces. Many of their lessons — mobility, adaptability, and the power of citizen-soldiers — still resonate in modern military doctrine. Each regiment, in its own way, reflected the diversity and determination of the American cause. They were not merely fighting for independence — they were defining what it meant to be American. Through their endurance and sacrifice, the Continental Army’s extraordinary regiments secured not only freedom but the birth of a new national identity.

![[Video] Women of the American Revolution](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-29-at-3.53.33 PM.png)

![[Video] Women of the American Revolution Part 2](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-12-at-2.54.41 PM.jpg)