The Doan Gang of Bucks County: America’s Revolutionary Rogues

During the American Revolution, the Doan Gang of Bucks County became infamous for their daring crimes and unwavering loyalty to the British Crown. Led by a group of Quaker-born brothers and associates, the gang operated as spies, thieves, and horsemen who defied Patriot rule. While some viewed them as criminals, others saw them as rebels against an emerging government they refused to support. Their exploits, including high-profile robberies and intelligence gathering for the British, cemented their place in American history as both outlaws and political dissidents.

The Doan Gang’s story is one of conflict, betrayal, and survival in a time of war. Their ability to evade capture, their notorious theft of the Bucks County Treasury, and their eventual downfall turned them into legends of Pennsylvania folklore. Though the Revolution was fought between armies, the Doans proved that resistance could come from unexpected places. Their actions challenged the Patriots’ dominance and left a legacy that still lingers in Bucks County today.

The Doan Family and Their Quaker Roots

The Doan family hailed from Bucks County, Pennsylvania, a region deeply tied to Quaker traditions and pacifist beliefs. As members of the Religious Society of Friends, the Doans were raised in a faith that emphasized peace, honesty, and a commitment to nonviolence. Their ancestors had settled in Pennsylvania seeking religious freedom, and for generations, the family had lived quietly as farmers and tradesmen. However, as tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain escalated, the Revolutionary War forced difficult choices upon them, dividing their community and testing their loyalties.

Quakers generally opposed war, refusing to take up arms or swear allegiance to any government, whether British or Patriot. Many remained neutral, believing that both sides had abandoned the Quaker principles of peace and integrity. However, neutrality became increasingly difficult as the war progressed. Some Quakers, feeling pressure from both factions, chose to align with one side or the other. The Doan brothers—Moses, Levi, Aaron, Mahlon, Joseph, and Abraham—ultimately sided with the British, seeing the Revolution as a rebellion against established rule rather than a fight for freedom.

The decision to support the British was not uncommon among Quakers, as many still considered themselves loyal subjects of King George III. The Doans believed the Patriot movement was oppressive and hypocritical, forcing those who disagreed with them to submit or suffer consequences. Patriots in Bucks County demanded oaths of loyalty, imposed fines on those who refused, and confiscated the property of suspected Loyalists. For the Doans, who had been raised in a faith that discouraged government interference, these actions justified their opposition to the revolutionary cause.

Though Quakers preached nonviolence, the Doan brothers abandoned this principle, embracing espionage, theft, and even deadly force in their fight against the Patriots. This shift from peaceful farmers to notorious outlaws reflected the complexities of the Revolutionary War, where families were torn apart by competing allegiances. The Doans were not content with merely rejecting the Revolution; they actively worked to undermine it, using their knowledge of Bucks County to outmaneuver local authorities and aid the British cause.

Their transformation from Quaker pacifists to feared outlaws was fueled by both ideology and personal survival. By refusing to swear loyalty to the Patriot cause, they faced the threat of imprisonment or worse. Their rejection of Patriot authority led them down a path of crime and resistance, making them both legendary and infamous in Pennsylvania’s wartime history. The story of the Doan gang is a striking example of how war forces individuals to abandon deeply held beliefs in the face of political upheaval.

The Doan Gang and Their Loyalist Allegiances

As tensions between Patriots and Loyalists escalated, the Doan brothers pledged their loyalty to the British, becoming key informants and spies for the Crown. In July 1776, Moses and Levi Doan personally met with British General William Howe, offering their services as intelligence operatives. Recognizing Moses Doan’s ability to navigate the Pennsylvania countryside undetected, the British granted him the nickname “Eagle Spy” for his keen instincts and effectiveness in gathering intelligence. By this time, most able-bodied men had joined the Patriot militias, leaving much of Bucks County vulnerable to Loyalist activity, allowing the Doan Gang to operate with little opposition.

Moses Doan quickly proved invaluable to the British. On August 27, 1776, he provided General Howe with critical intelligence regarding the unguarded Jamaica Pass, a little-known path in Brooklyn, New York. This information allowed the British to flank and overwhelm General George Washington’s forces during the Battle of Long Island, forcing the Continental Army into retreat. This decisive British victory, made possible in part by Doan’s reconnaissance, strengthened British control over New York City and demonstrated how effective Loyalist spies could be in shaping the course of the war.

Later that year, as the Continental Army struggled to survive the winter of 1776, the Doan Gang continued their espionage efforts. On December 25, 1776, the night of Washington’s famous crossing of the Delaware River, Moses Doan was rumored to have delivered a critical warning to Hessian Colonel Johann Rahl, who commanded the British-allied troops in Trenton, New Jersey. The note reportedly read: “Washington is coming on you down the river, he will be here afore long. Doan.” However, Colonel Rahl never read the message, dismissing it as unimportant.

As a result, Washington and his troops were able to surprise the Hessian forces, securing a pivotal Patriot victory at the Battle of Trenton—a turning point in the war. Had Rahl heeded Doan’s warning, the outcome of the battle, and perhaps even the war, might have been drastically different.

The Doan Gang’s value to the British extended beyond battlefield intelligence. They served as couriers between Loyalist sympathizers and British commanders, using their deep knowledge of Bucks County’s terrain to evade Patriot patrols. Their ability to blend in among local communities allowed them to operate in secrecy, relaying messages and coordinating Loyalist efforts in Pennsylvania and beyond. With the British relying on informants to disrupt Patriot strategies, the Doans played a vital role in keeping the Crown informed about enemy movements.

While their actions earned them the trust of British commanders, they also made the Doan Gang some of the most wanted men in Pennsylvania. Patriot authorities viewed them as dangerous traitors, and efforts to capture them intensified as the war progressed. However, their connections with Loyalist militias and sympathizers ensured that they remained a formidable force, operating in defiance of the revolution and shaping key moments of the war through their intelligence work.

Crimes and Notorious Activities

As the Revolutionary War continued, the Doan Outlaws evolved from spies and Loyalist operatives into one of the most notorious criminal gangs in Pennsylvania. Their principal occupation was robbing Whig tax collectors and stealing horses, acts that directly undermined the Patriot cause. The Doans targeted tax collectors as symbols of the new American government, raiding their homes and confiscating funds that were meant to support the war effort. Their growing reputation for robbery and deception made them infamous throughout Bucks County and beyond. While they claimed to act in the name of the British Crown, their activities often blurred the line between political loyalty and outright banditry.

The Doan Gang was especially known for horse theft, stealing over 200 horses from their Patriot-aligned neighbors in Bucks County. These stolen horses were then sold to British troops in Philadelphia and Baltimore, providing the Redcoats with valuable resources while enriching the gang. The Doans’ deep knowledge of Pennsylvania’s countryside allowed them to strike quickly, taking prized horses under the cover of night and disappearing before authorities could respond. Their ability to evade capture made them legendary, and Patriot officials considered them a major threat to the American war effort.

The gang’s violent reputation grew, leading to controversial accusations of murder. On June 7, 1780, Abraham Doan was allegedly involved in the killing of a woman in her home while her nine children huddled around her in terror. Though this claim appears in multiple sources, there is no definitive proof, and the woman’s husband later refuted the story. However, a 1788 broadside about Abraham and Levi Doan confirmed that a French merchant on the Susquehanna River died from wounds inflicted by the gang. The Doans were also documented in Pennsylvania state archives as having threatened to kill tax collectors who resisted their demands.

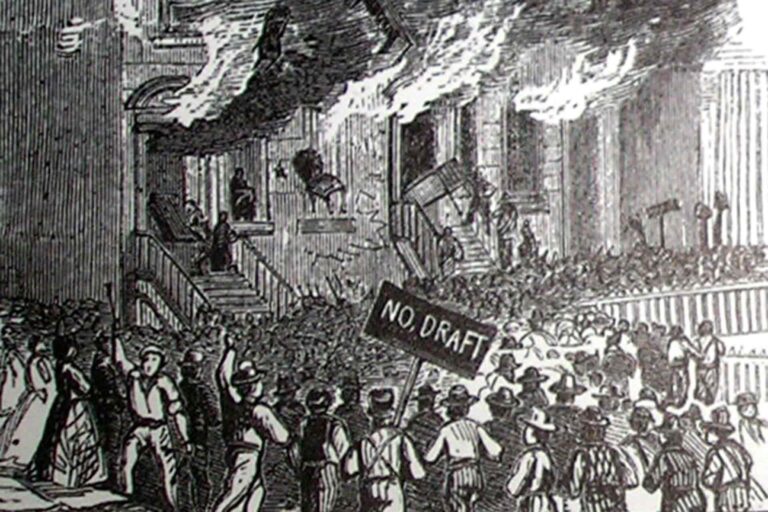

One of their most infamous crimes occurred on October 22, 1781, just three days after British General Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown. The gang successfully raided the Bucks County Treasury in Newtown, making off with 1,307 pounds sterling—a massive sum at the time, equivalent to over £200,000 today. The stolen funds, meant to finance Patriot operations, were never recovered. This heist cemented their status as master criminals who could strike at even the most secure locations. With the war winding down, their continued raids put them in direct conflict with the emerging American government, and their actions were no longer seen as just Loyalist resistance, but as high-stakes criminal activity.

Beyond high-profile heists, the Doan Gang routinely targeted tax collectors across Pennsylvania. Between 1782 and 1783, they robbed at least nine tax officials, often attacking them in their homes at night. These raids were not only financially motivated but were also a deliberate effort to disrupt the government’s ability to collect funds. In June 1783, Moses and Abraham Doan led a series of coordinated robberies against multiple Bucks County tax collectors, prompting officials to place a 100-pound bounty on their capture—an enormous sum for the time (over £15,000 today).

Despite mounting pressure from Patriot authorities, the Doans proved difficult to catch. Their intimate knowledge of Bucks County’s forests, caves, and safehouses allowed them to evade capture for years. They relied on a network of Loyalist sympathizers who provided shelter and supplies, frustrating Patriot officials at every turn. Even when surrounded by law enforcement, they often managed to escape through hidden routes and well-planned diversions. Their skill in evasion and their audacious raids solidified their reputation as America’s most infamous Revolutionary outlaws.

The Pursuit and Capture of the Doan Gang

As the Revolutionary War came to a close, Pennsylvania authorities intensified their efforts to bring the Doan Gang to justice. The gang’s continued robberies, association with the British, and violent reputation made them a pressing concern for the new government. Despite the growing number of bounties placed on their heads, the Doans skillfully evaded capture by using their deep knowledge of the Pennsylvania countryside and relying on Loyalist sympathizers for shelter and supplies. Law enforcement officials, frustrated by repeated failed attempts to capture the gang, began organizing more aggressive search efforts to put an end to their reign.

On August 28, 1783, a posse of 14 armed men received word of the gang’s location and set out to apprehend them. In the ensuing confrontation, Levi and Abraham Doan managed to escape, but Moses Doan was killed while resisting arrest. During the skirmish, Major Kennedy, a member of the posse, was struck by a bullet fired from a Doan weapon and succumbed to his wounds three days later. Authorities later found a note in Moses Doan’s pocket, threatening to assassinate United States Speaker of the House Frederick Muhlenberg if Joseph Doan was not released from prison. This revelation underscored the gang’s continued defiance, even in the face of death.

Following Moses’ death, Pennsylvania officials increased the reward for the remaining members to 300 pounds each, signaling the government’s resolve to eliminate the gang. The increased bounty heightened the pressure on the remaining fugitives, leading to further arrests. Mahlon Doan managed to escape from a Bedford, Pennsylvania jail in 1783 and fled to New York City, where he disappeared from recorded history. In 1784, Joseph Doan Jr., sentenced to death for murder, broke out of a Newtown jail and fled to New Jersey, where he lived under an assumed identity as a schoolteacher. His ruse was eventually discovered, forcing him to escape once more, this time to Canada, where he spent the rest of his life in exile.

Aaron Doan was captured and sentenced to death for his crimes. However, in 1787, he was granted a pardon on the condition that he permanently leave the United States. While some gang members escaped execution, Levi and Abraham Doan were not as fortunate. Captured and convicted of treason, they admitted to aiding the British, and on September 24, 1788, they were hanged in Philadelphia. Their execution marked the official end of the Doan Gang’s notorious operations, though their legacy as outlaws would endure in Pennsylvania folklore.

Moses Doan was buried in Plumstead Township, but over time, his gravestone was moved and now rests in a nearby hedgerow, its inscription worn away by years of exposure. Levi and Abraham were denied burial within the Friends Meeting House cemetery in Plumsteadville due to their association with violence, which conflicted with the Quaker commitment to pacifism. Instead, they were buried just outside the cemetery’s stone wall. Their original headstones, made of native brownstone, bore no inscriptions in keeping with Quaker traditions of the era. More recent markers have since been added, recognizing them as outlaws and preserving their place in Bucks County history.

Public Opinion of the Doan Gang

The Doan Gang evoked a mix of fear, resentment, and admiration among the people of Bucks County and beyond. To Patriot communities, they were dangerous criminals—Loyalist traitors who robbed Whig tax collectors, aided the British, and terrorized local towns. Their ability to evade capture for so long frustrated authorities, while their violent raids and robberies instilled fear in those who supported the American cause. Many viewed them as ruthless outlaws who sought personal gain under the guise of political allegiance, undermining the fragile new government in the aftermath of the Revolution.

However, among Loyalist sympathizers, the Doans were seen in a very different light. Some regarded them as folk heroes—rebels who resisted the Patriot-led government and struck back against those who had confiscated Loyalist property or forced families into exile. Their ability to outmaneuver law enforcement and escape repeated capture only added to their legend. Even long after their deaths, stories of the Doan Gang persisted in Pennsylvania folklore, with some tales exaggerating their exploits and painting them as daring highwaymen rather than mere criminals.

The divide in public opinion was also shaped by personal experience. Those who had been robbed or threatened by the Doans saw them as violent brigands, while others, especially Loyalist families, considered them victims of political persecution. Over time, their legacy evolved into a blend of history and legend, with some historians acknowledging their cunning and resourcefulness even as they remained a cautionary tale of divided loyalties during the Revolutionary War. Their story endures in Bucks County as a reminder of the war’s internal conflicts and the fine line between patriotism and outlawry.

The Doan Legacy

The story of the Doan Gang has been woven into the folklore of Bucks County, passed down through generations as a tale of outlaws, rebellion, and survival. While their crimes were well-documented, time has blurred the line between fact and legend, with some accounts portraying them as daring highwaymen rather than mere criminals. Their ability to evade capture for so long and their ties to Loyalist espionage have given them an almost mythical status in local history. Even today, their name sparks intrigue, with historians and storytellers debating whether they were ruthless traitors or misunderstood revolutionaries.

One of the most enduring legends surrounding the Doan Gang is the mystery of hidden treasure. Some believe that before their capture, the gang buried a fortune in stolen gold and silver somewhere in Bucks County. Over the years, treasure hunters have searched the countryside, hoping to unearth the Doans’ lost wealth. While no verified treasure has ever been found, the speculation adds to the gang’s mystique, keeping their story alive in local lore. Their most infamous heist—the robbery of the Bucks County Treasury—fueled the belief that their loot remains hidden, waiting to be discovered.

Beyond folklore and treasure tales, the Doan Gang holds a unique place in American history as symbols of rebellion and resistance. Though they were Loyalists who opposed the Patriot cause, their story reflects the internal divisions that tore communities apart during the Revolution. Their actions, whether seen as defiance or lawlessness, highlight the chaos and uncertainty of a nation in transition. Unlike traditional accounts of Revolutionary War heroes, the Doans’ legacy is more complicated, illustrating that not all who fought or resisted in the war did so for noble reasons.

Their impact can still be seen today in Bucks County, where historical markers and oral traditions ensure that their story is not forgotten. Historians continue to debate the extent of their crimes and the true nature of their motivations. Were they self-serving criminals, or did they genuinely believe in the Loyalist cause? The Doan Gang’s legacy remains an open-ended question, a reminder of the fine line between patriotism and outlawry in the tumult of revolution.