Queen Victoria and the Making of the Victorian Age

Victoria: A Queen and an Era

When the young and untested Queen Victoria inherited the throne of Great Britain and Ireland in 1837, it was perhaps impossible to foresee that her reign would one day name an entire era. An inexperienced royal figure, who became monarch against the odds of public scandal just a few years before, Victoria in fact became the face of 19th-century Britain. Her six-decade reign was marked by a quiet continuity that matched the scale of the profound social, economic, and cultural changes of the era: so much so that historians have come to characterize not just her reign, but the entire period as the Victorian Era.

The Victorian Age is one of the most impactful in modern British and world history. The great clanging factories and burgeoning railways, the scope of imperial power and global trade, the dynamic currents of social reform and high cultural confidence–these were also the inequalities and problems, tensions and exploitations, of a world on the cusp of the modern age. The 64-year rule of Queen Victoria marked, shaped, and symbolized these forces, overseeing and embodying a nation and a world transformed by industrial and imperial power, moralizing social reform, and thrilling contradiction.

Queen Victoria and the Transformation of the Monarchy

Victoria inherited a monarchy that had lost much of its political influence and suffered in the public eye due to a long history of scandals and profligacy. The change in role that Victoria oversaw from monarch as political power broker to the crown as national symbol was a critical evolution for the British monarchy to continue as the United Kingdom expanded democratic reforms and increased the power of Parliament in the 19th century.

As monarch, Victoria was very intentional about re-establishing the dignity and respect of the crown. Prior kings and queens had been linked to corruption, affairs, and lavish spending; Victoria became the antithesis of these behaviors by emphasizing duty, moderation, and sobriety. In one of her journals, Victoria once wrote that the role of a monarch was to reign “for the good of the people, not for self-indulgence.” Her image as a dignified and responsible ruler was critical to the crown’s efforts to regain public trust during an era of great social upheaval.

The emphasis on family was also key to Victoria’s success as a modernizing monarch. The marriage of Victoria and Prince Albert in 1840, and the continual rearing of their children and, later, their grandchildren, as a visible family under strict protocols, solidified an image of stability at a time of uncertainty. The ideals of marriage, child rearing, and responsibility that Victoria and Albert created in their marriage, widely disseminated through images, state occasions, and the royal tours of the United Kingdom, became the hallmark of Victorian morality and appealed to the sensibilities of the growing middle class.

Prince Albert was not only the model husband and father but also an active political advisor to his wife, supporting many educational reforms and movements promoting science and industry. Albert’s patronage of the Great Exhibition in 1851, which showcased Britain’s modernization and industrialization, was a particular highlight of his efforts. In his own way, Albert reinforced the monarchy as a symbol of the country’s progress, rather than a threat or challenge to Parliament’s work.

In redefining the crown as a moral and national figurehead, Victoria allowed the monarchy to survive and endure during a time of reform and upheaval across the world. The crown no longer had the power over Britain it had held in earlier generations. Still, as a visible symbol of stability in Victoria’s reign, it had become something more lasting and respected at home and abroad.

Queen Victoria, Parliament, and the Balance of Power

The constitutional landscape during Victoria’s reign saw a gradual transfer of real power from the monarchy to Parliament. The Reform Acts broadened the franchise, strengthened the House of Commons, and limited the monarch’s direct authority. Victoria accepted these constitutional changes with good grace and a clear-eyed realism. She recognized that the long-term survival of the monarchy required adaptability within the constitutional framework, rather than obstinate resistance to democratic evolution.

In public, Victoria’s political role was circumscribed by these constraints. Privately, however, she remained deeply engaged in politics and retained significant influence behind the scenes. The Queen corresponded extensively with her prime ministers, including Lord Melbourne, Lord Palmerston, and Benjamin Disraeli. Through letters, Victoria sought to offer advice, express concerns, and keep abreast of foreign and domestic developments. In one notable example, she once wrote, “The Queen is most anxious to hear every detail.”

Victoria was astute in her approach to navigating the challenges of democratic reform. She learned to avoid public political battles, yet she deftly preserved the monarchy’s right to be consulted, to encourage, and to warn.

This allowed her to influence appointments, diplomacy, and the overall direction of policy, without overstepping boundaries and risking public outcry or parliamentary crisis.

By accepting her constitutional role and adapting to the shifting political landscape, Victoria ensured the monarchy’s long-term stability. The institution of the crown emerged from the Victorian era not diminished, but on firmer footing. The monarchy was now seen as a respected national institution that could weather political change while maintaining a quiet and enduring influence.

Industrial Expansion and Innovation

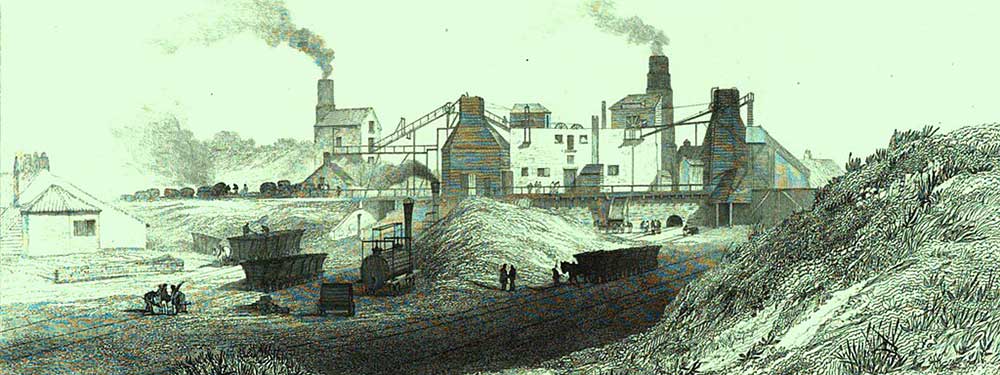

The British Industrial Revolution was well underway by the start of Victoria’s reign in 1837. Her reign, however, would see Britain become the world’s first industrial nation. The number of factories rapidly increased, powered by coal and iron, and Britain was heralded as “the workshop of the world”. Manufactured goods were shipped from British ports to every continent. Her majesty’s empire had unparalleled economic power and influence, and its rivals could not compete with the wealth of Britain.

Railways also became a dominant part of the Victorian landscape and daily life. New tracks were laid by the thousands of miles connecting cities, ports, and factories, revolutionizing transport. These railways were connected by steamships, revolutionizing sea travel as well, enabling the exchange of British goods, people, and ideas on a global scale. The engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel confidently told a friend, “Progress was only limited by the imagination of mankind.

Industrial growth also changed the makeup of Britain itself. Rural communities migrated to cities for employment in the growing manufacturing industry, including Manchester, Birmingham, and London. Social mobility created an expanding industrial middle class and a swelling urban workforce. Life for many laborers became harder due to overcrowding, pollution, and poor housing.

Mechanization also changed the daily lives of those living through the Industrial Revolution. Factory bells regulated time and day instead of the rising and setting of the sun. Traditional crafts and trades were replaced by machine production. The author Charles Dickens, among others, was concerned about the impact of industrialization on the poor. He was particularly concerned about the use of “machinery and steam power” and the potential it had to “grind them [the poor] to powder”.

Expansion of the British Empire

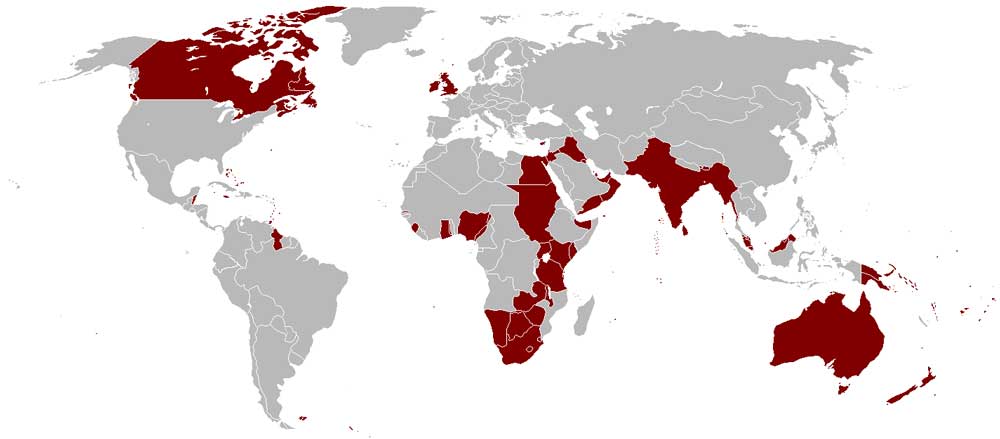

Queen Victoria’s rule coincided with the peak of the British Empire’s power and influence. At its height, the British Empire was the largest in history, covering about a quarter of the world’s land area and population. By the late 19th century, the British had colonies on every inhabited continent, and it was said that “the sun never sets on the British Empire.”

India was the jewel in the British Empire’s crown. The British had been involved in India for centuries, but it was during Victoria’s reign that the full-fledged empire was established. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 led to the dissolution of the East India Company and the transfer of power to the British Crown. The Queen took a personal interest in India, and in 1876, she was proclaimed Empress of India.

The title of Empress not only affirmed Britain’s claim to India but also tied the monarchy to the British Empire. It also served to enhance Britain’s status as a global power and to symbolize the crown over such a vast and diverse population.

The British Empire expanded in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Islands through a combination of military conquest, treaties, and economic pressure. Colonies provided raw materials for British industry, markets for British goods, and naval bases to protect trade routes. Military force was used to maintain control, and colonial administrations were established to oversee local affairs, often imposing British legal and educational systems and values.

The Empire was a source of wealth and power for Britain, but it was also built on the exploitation and subjugation of indigenous peoples. Colonial economies were disrupted, land was often confiscated, and labor and taxation systems were often biased in favor of British interests over local ones. As one contemporary critic wrote, the empire promised “civilization” but all too often delivered “plunder.”

The legacy of Victorian imperialism is still felt around the world today. Many of the borders of modern nation-states were drawn during this period, contributing to some of the conflicts we see today. The economic and cultural impacts of British colonialism are also still present in many former colonies. Victoria’s empire was a defining feature of the modern world, and its legacy is complex and often controversial.

Social Reform and Victorian Moral Ideals

Victorian morality was associated with Queen Victoria and the expansion of the British Empire. Respectability, self-control, religious faith, and family life were all valued as social virtues and middle-class ideals that the queen embodied as a wife and mother. Moral behavior was increasingly seen as a personal responsibility and a measure of national greatness.

The social problems associated with industrialization were also brought to the public’s attention. The long hours and poor working conditions endured by children in factories, mines, and workshops caused widespread public indignation. Reformers, such as Lord Shaftesbury, led campaigns to restrict child labor, and many activists argued that “the labour of children…was a national disgrace”. A succession of Factory Acts limited working hours, improved working conditions, and extended the provision of schooling to poorer children.

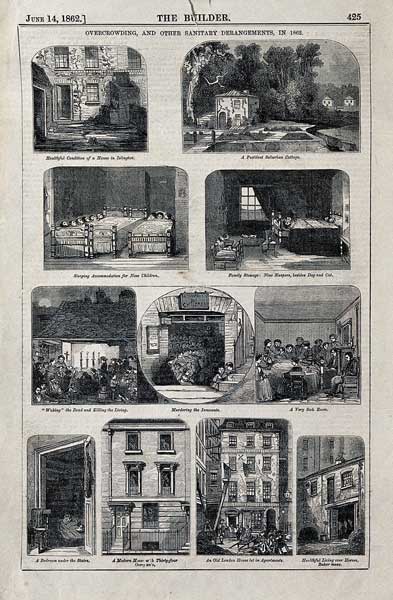

The crowded and insanitary conditions in British cities now came under increasing attack. The outbreaks of cholera and other diseases, as well as the high death rates in urban areas, forced public authorities to take action. Measures were taken to improve sewerage, supply clean water, and remove household waste. These sanitary reforms had a marked impact on the quality of urban life. The Victorian era also saw a growing conviction that the state had a duty to intervene to safeguard the public’s welfare.

Attempts were also made to improve the quality of working-class housing. Investigations into urban slums revealed overcrowded and insanitary conditions, as well as dangers from poorly constructed and fire-prone dwellings. Legislation on housing sought to enforce regulations on ventilation, safety, and sanitation, though improvements were patchy. Despite well-intended reforms, many people continued to live in poverty in Victorian Britain.

There were also limitations to Victorian reform. Social inequality remained endemic, women were denied political rights, and moral considerations were not extended to colonial subjects. The values of Victorian society inspired change, but they often failed to challenge the underlying power dynamics and hierarchies.

Scientific and Intellectual Advancement

During the Victorian Age, the drive to discover and to know new things flourished, inquiring into areas which had previously been sacrosanct. The previously accepted world of God, nature, and humanity, and the view of Victorian society as the product of these three, was challenged. The most significant shift in Victorian culture was in the domain of “religion” as Victorian society was confronted by science. The new importance of the methodical observation, experimentation, and classification of objects, whether in distant or more immediate environments, redefined the role of science and its relation to the world previously experienced.

This process had no clearer embodiment than On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin. Published in 1859, the book challenged the widely held view of static, unchanging species and raised questions about how, if not by a divine creator, living things had developed. Some Victorians were appalled by the work and wanted to distance themselves from its teachings; others were ready to accept it as the answer to old questions. Darwin himself observed in his introduction that the implications of the work “will throw light on the origin of man”, a statement that sent shockwaves throughout a Victorian society which began to read and discuss the scientific text with fascination.

The advance of medical science and related technologies was also rapid. Knowledge of anatomy and surgery, of hygiene and sanitation, improved rapidly during Victoria’s reign. A range of scientific techniques tackled infection and death in hospitals. By the end of the period, a range of well-publicized and successful figures, such as Joseph Lister, were giving practical expression to the view that knowledge could and should be used to improve life.

Science was applied in many other practical ways. Bridges, railways, canals, telegraph wires, and buildings dominated the Victorian landscape, as did steam-powered machines, as we mentioned above. Major public exhibitions, notably the Great Exhibition of 1851, were intended to show off Britain’s manufacturing and technical supremacy to the world.

The process of discovery and change, the collision of old and new views, and the debate about the shape of the future began to replace a simple “faith in progress” with a questioning of how to ensure progress was for the better. Many Victorians sought a simple solution by choosing to believe in either religion or science, but the era was, in many ways, defined by debates between the two. Science in the Victorian Age both answered and asked questions.

Cultural Confidence and Its Contradictions

Victorian Britain was a time of great creativity in literature, art, and architecture. Public buildings, museums, railway stations, and the growth of suburbs were accompanied by Gothic Revival churches and neoclassical monuments. Architecture was seen as an expression of progress, empire, and morality. In art and design, there was an emphasis on creating beauty alongside the concerns of industrial modernity.

Victorian writers described the social cost of change with great power. Charles Dickens exposed poverty, child labour, and injustice in novels like Oliver Twist and Hard Times, memorably characterizing London as a city of “wealth and want”. The Brontë sisters wrote about inner lives and social restriction. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, expressed doubt, faith, and national pride in poetry.

The cultural high points of Victorian Britain celebrated invention and moral progress. Yet extreme poverty and inequality persisted. Industrial wealth and new technologies made the lives of factory owners and financiers more comfortable, but the growing urban poor faced dangerous housing, dirty streets, and uncertain employment. In slums shadowed by Victorian prosperity, millions of people endured poverty and disease.

A stark example of the limits of Victorian cultural self-confidence was the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s. Queen Victoria did feel a measure of personal sympathy for Irish victims (as evidenced in her private correspondence), and she made private donations for famine relief (earning her the sobriquet of “the Famine Queen” from some of her supporters).

However, the Irish catastrophe was met mainly by a Parliamentary policy of laissez-faire, limited intervention, and continued food exports. Aid was patchy and often withdrawn prematurely in the belief that a moral hazard would be created if food was given out too easily.

Intellectual life and culture reflected tensions between achievement and human cost. Art and literature expressed both pride in progress and concern for the vulnerable. By giving expression to exploitation and inequality, Victorian artists and writers were part of debates about responsibility, reform, and what it meant to be modern.

Gender, Family, and Social Expectations

Queen Victoria’s influence helped shape Victorian ideals about family, womanhood, and moral order. Her public persona presented an image of domestic stability, with the monarch as a model of wifehood and motherhood. She and Prince Albert symbolically represented the belief that a proper family life was both a private virtue and a public duty to be emulated by all British citizens.

Victorian gender ideals, influenced by this, assigned strict social roles to men and women. Men were associated with the public sphere of politics, commerce, and industry, while women were encouraged to focus on the private worlds of home and family. The well-known figure of “the angel in the house” idealized women as self-sacrificing, tender, and devoted exclusively to the family and household.

Victorian moralism also concealed stark contradictions and social problems. Public discourse stressed purity, restraint, and propriety, while prostitution, exploitation, and concealed poverty were significant features of many industrial cities. The distance between the respectable façade and private realities exposed tensions within an empire struggling to balance morality and economic and social change.

Women had minimal political and legal rights for much of the Victorian period. Married women had little or no control over property, income, or children, and these issues began to change only with gradual reforms late in the century. Despite these legal constraints, women’s roles in society were beginning to change through education, reform work, and early suffrage campaigns.

By the end of the queen’s reign, the strict social codes popularized by Victorian morality were under increasing pressure. The Victorian ideal of family life persisted, but demands for greater equality and individual freedom foreshadowed challenges to traditional gender roles.

Lasting Traditions and Public Ritual

Queen Victoria’s reign transformed royal ceremony into a powerful tool of national identity. Public appearances, jubilees, and carefully staged rituals became more frequent and meaningful, allowing the monarchy to connect directly with a rapidly growing population. Events such as Victoria’s Golden and Diamond Jubilees drew enormous crowds and reinforced the crown’s role as a unifying presence in an age of social change.

The Victorian royal family also reshaped domestic traditions, most famously at Christmas. Victoria and Prince Albert popularized the decorated Christmas tree, gift-giving, and family-centered celebrations. Illustrated magazines depicted the royal household celebrating together, turning the monarchy into a model of respectable family life for the nation.

New media played a crucial role in shaping this public image. Advances in printing, photography, and mass journalism allowed the monarchy to be seen as never before. Victoria became one of the first monarchs whose likeness circulated widely through photographs, engravings, and newspapers.

This visibility helped humanize the crown while preserving its dignity. As one observer noted, the queen was “known to her people not only as a ruler, but as a woman and a mother.” Through ritual, tradition, and media, Queen Victoria ensured the monarchy remained emotionally connected to the public.

By the end of Queen Victoria’s reign, these practices had become enduring features of British life. Modern royal ceremonies, public celebrations, and seasonal traditions still reflect patterns established during the Victorian age.

Reflecting on Queen Victoria and the Victorian Age

The Victorian Age was a time of extraordinary power and progress, but also profound contradiction. Britain had become the center of a global empire, driven by industrial might, scientific discovery, and cultural confidence. Yet, at home and abroad, vast inequalities and exploitation persisted. As one contemporary put it, it was an age that “believed in improvement”, even as it grappled with the human cost of that belief. These tensions between progress and exploitation, faith and skepticism, shaped a world that felt both modern and unsettled.

At the heart of this world was an English Monarch: Queen Victoria. Her long reign reshaped the monarchy into a symbol of stability, morality, and national identity. The institutions, traditions, and global systems forged during her lifetime laid the foundations for the modern industrial economy, constitutional politics, and international culture. Long after her death, the Victorian Age continues to shape how societies understand power, progress, and responsibility in an interconnected world.