Survival and Migration: The Human Impact of the Irish Potato Famine

The Irish Potato Famine, which devastated Ireland between 1845 and 1852, stands as one of the most tragic events in modern history. At its core, it wasn’t just a tale of crop failure but a profound human catastrophe marked by widespread hunger, suffering, and an unparalleled demographic shift. “Survival and Migration: The Human Impact of the Irish Potato Famine” delves into the profound ways this calamity reshaped the Irish populace.

As families faced dire starvation, many made the agonizing decision to leave their homeland in search of sustenance and hope. This mass exodus not only redefined the very fabric of Irish society but also left an indelible mark on the global diaspora. In this exploration, we will unearth the resilience, desperation, and the quest for survival that defined an era.

Ireland Leading Up to The Irish Potato Famine

In the decades leading up to the Irish Potato Famine, Ireland was a land marked by both its picturesque landscapes and its socio-economic disparities. Under British rule, the majority of the Irish population lived as tenant farmers, tilling plots of land owned by often absentee English landlords. These landlords, drawn by the economic prospects of grain exports, allocated the best land for grain production, leaving the less fertile plots for their Irish tenants. Consequently, many Irish farmers were left with little choice but to cultivate potatoes, a crop that thrived even in the less fertile soils and provided essential sustenance for their families.

The potato became more than just a staple; it was the very lifeblood of Irish agrarian society, with an estimated two-fifths of the population entirely dependent on this single crop for their nutrition.

However, this dependency was set against a backdrop of broader economic and political challenges. Ireland’s incorporation into the United Kingdom in 1801 meant that its economy was closely tied to that of Britain. While this union led to increased trade and the modernization of some sectors, it also meant that the majority of Ireland’s agricultural produce was exported to feed Britain’s burgeoning urban populations. The Irish, despite living in an agrarian society, found themselves in an ironic predicament: while they exported vast quantities of grain, they remained reliant on a single, vulnerable crop for their survival.

The societal structure further exacerbated these challenges. The Penal Laws, though relaxed by the early 19th century, had left a lasting legacy of religious and economic disenfranchisement for the Catholic majority. Land ownership, political power, and economic opportunities remained largely in the hands of the Protestant minority.

This concentration of power and wealth created a fragile socio-economic structure, one that, when faced with the impending blight of the mid-1840s, would prove devastatingly inadequate in its response to the needs of the Irish people. As the dark clouds of the Irish Potato Famine began to gather, Ireland stood on the precipice, its people unknowingly poised for one of the gravest trials in their nation’s history.

The Blight Begins & Then Rages

The beginnings of the Irish Potato Famine can be traced back to an insidious intruder, Phytophthora infestans, a strain of water mold. First reported in the United States in the early 1840s, and later in Belgium, this disease made its appearance in Ireland in 1845. Initially showing up as mysterious black spots on potato leaves, the blight rapidly spread, decimating entire fields and rendering the afflicted potatoes inedible. As the potatoes were dug up, they were found to be rotten with a foul odor, turning a staple food source into mushy waste.

The speed and scale at which the blight struck were unprecedented, and its impact was felt most acutely in a country where so much of the population relied heavily on this single crop.

As the blight ravaged successive potato harvests from 1845 to 1852, the consequences for Ireland were catastrophic. With each passing year, the extent of the crisis deepened, turning fields that were once brimming with life into barren landscapes. Without their primary food source, starvation became rampant, exacerbated by a lack of diverse food supplies and the continued export of other agricultural produce to Britain. This mass hunger was soon accompanied by diseases like typhus, cholera, and dysentery, which found fertile grounds in the weakened and malnourished population.

The socio-economic structure of Ireland, already strained before the famine, crumbled under the weight of this calamity. Tenant farmers, unable to produce enough crops to pay their rents, faced evictions en masse. Many rural families, evicted or not, found themselves with no other option but to leave their homes in search of work, food, or aid. The roadsides became dotted with makeshift huts and shanties, while workhouses, designed to offer relief to the destitute, were overwhelmed.

Yet, the landscape of Ireland was altering in more permanent ways too. The devastation of the Irish Potato Famine prompted an unprecedented wave of emigration. Estimates range from 1-2 million Irish emigrating, hoping to escape the clutches of death and despair, left their homeland. Ships bound for North America, Australia, and other parts of the world became overloaded with desperate Irish souls, many of whom would never set foot on their homeland again. This diaspora changed the demographics of Ireland, draining it of a significant portion of its young and able-bodied population.

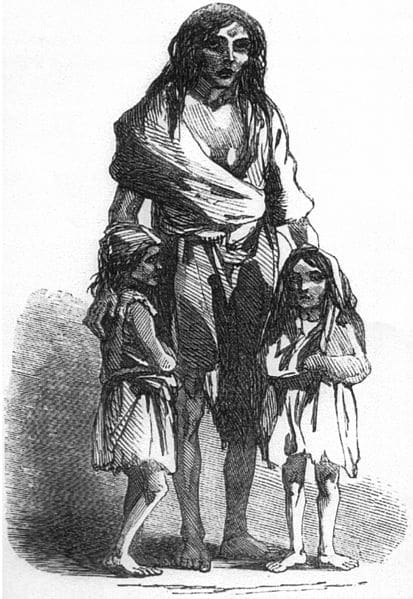

During the grim years of the Irish Potato Famine, death became an all too familiar specter, looming ominously over the Irish populace. At the core of the fatalities was acute starvation. As fields turned barren and food stocks dwindled, many Irish families were faced with the heart-wrenching reality of having nothing to eat. Malnutrition led to weakened immune systems, making individuals more susceptible to diseases. Epidemics of typhus, relapsing fever, cholera, and dysentery tore through communities, often claiming as many lives as hunger itself. Compounding this, the conditions in which many lived during the famine – from crowded workhouses to makeshift shanties along roadsides – were breeding grounds for these diseases.

Tragically, the very places intended to offer relief, like workhouses, became epicenters of contagion. The dire circumstances of the famine, thus, transformed the Emerald Isle into a landscape of despair, marked by the hauntingly skeletal figures of its inhabitants and the omnipresent shadow of death. It is widely accepted that at least one million Irish citizens died from starvation and associated illnesses.

Irish Sentiment Towards Great Britain During the Irish Potato Famine

The Irish Potato Famine not only wreaked havoc on the land and its people but also intensified the longstanding tensions between Ireland and its British rulers. As the blight decimated potato crops, many Irish citizens grew increasingly resentful of British policies, which they perceived as indifferent or even hostile to their suffering. One significant point of contention was the continued export of grain, meat, and dairy products from Ireland to Britain, even as Ireland’s population starved.

These exports were facilitated by the Corn Laws, which protected British grain producers from cheaper foreign competition, ensuring that Irish grain remained a profitable export to the British market.

Additionally, British relief measures, such as the establishment of public works projects designed to employ the Irish and provide them with wages to purchase food, were seen by many as inadequate and often mismanaged. The projects were notorious for being physically demanding, yet they provided meager pay, barely enough to sustain a family in the inflated famine economy. The introduction of the workhouses, intended to aid the destitute, further fueled resentment. They were often overcrowded and became hotspots for disease, leading to the perception that they were more punitive than charitable in nature.

The British government’s reluctance to intervene more directly in the food market, out of a staunch belief in laissez-faire economics, further intensified Irish grievances. Many in Ireland came to view the British response to the Irish Potato Famine, characterized by its minimal interference and reliance on market forces, as a reflection of systemic neglect or even a deliberate act of genocide. This profound sense of betrayal during the years of the Irish Potato Famine would later serve as a powerful catalyst for Ireland’s push for independence and forever shape its historical memory of the tragic period.

Ireland’s Slow Recovery & What the Emigrants Found Abroad

The conclusion of the Irish Potato Famine did not arrive with a sudden reversal of fortune but rather a gradual cessation of the blight and a series of changes in both agricultural practices and governmental policies. By 1852, the blight’s hold on the potato crops began to wane, and successive harvests started to show recovery. However, the end of the immediate crisis did not signal an instant return to normalcy. The damage had been done, and its repercussions would shape Ireland and its diaspora for generations.

Before the onset of the famine, Ireland’s population was approaching a staggering 8.5 million. By the end of the Irish Potato Famine, it’s estimated that a million had died from hunger and disease, and at least another million had emigrated in search of a better life. The result was a dramatic decline in the country’s population, and the trend continued, with many more Irish leaving in the subsequent decades. By the end of the 19th century, Ireland’s population had nearly halved.

The Famine Memorial sculpture on Custom House Quay is located on the departure site of the Perseverance, one of the first famine ships to leave Dublin in 1846. It shows a group of people about to enter the ship with various expressions of sadness, despair, and hope. – Bernd Thaller from Graz, Austria, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The majority of these emigrants sought refuge across the Atlantic, with the United States being a prime destination. Upon arrival, many Irish found themselves in bustling urban centers, where they often faced discrimination and were relegated to low-paying jobs. Their distinct accents, Catholic faith, and the sheer number of immigrants arriving made them stand out, often leading to tensions with native-born Americans and other immigrant groups.

However, their involvement in the American Civil War played a pivotal role in reshaping their image in their new homeland. Thousands of Irishmen, particularly those who had settled in the northern states, joined the Union Army. Their bravery in battle and sacrifices for their adopted country did much to elevate the status of the Irish community in America.

Elsewhere, Irish emigrants made their way to Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. In each of these destinations, they faced unique challenges but also made significant contributions to the societies they joined. They played integral roles in the development of these nations, from infrastructure projects to political arenas, even imparting aspects of Irish culture such as Halloween, and leaving an indelible mark.

Back in Ireland, the post-famine period was characterized by profound societal changes. The near-total reliance on a single crop had proven disastrous, prompting diversification in farming. Meanwhile, the trauma of the Irish Potato famine left deep scars on the national psyche, fueling nationalist sentiments and laying the groundwork for subsequent movements for Irish independence. The famine’s shadow loomed large over Ireland’s relationship with Britain, a memory of neglect and suffering that would take generations to heal. The Irish Potato Famine, in its devastation and aftermath, thus stands not only as a tragic episode but also as a turning point in the annals of both Irish and global history.