How the Marblehead Mariners Saved the American Revolution

The Marblehead Mariners were a group of Revolutionary War soldiers drawn from Marblehead, a fishing town on the Massachusetts coast. They were men who knew the sea long before they knew the sword, who had been fishermen and sea traders for much of their lives.

When the Revolution came, they were ready. When the Revolution was at its darkest, they made a difference. At Long Island in 1776 and on the Delaware River a few months later, it was the seamanlike genius and daring of the Marblehead men that prevented the destruction of George Washington’s army. In the process, they became one of the most reliable and disciplined regiments of the Continental Army.

Life on the ocean had also inured the Marbleheaders to the need for vigilance, precision, and attention to detail. Fishermen, merchants, and whalers knew well how to handle a craft in a storm or predict the changing tides and weather. Their work often required long voyages and great courage, as well as strong team spirit. Months and years at sea built up strength and reflexes. Their work itself required an innate knowledge of wind, weather, and tides, a sense of timing, and instinctive trust in their fellow crew members. When these same men took up arms and volunteered for Washington’s small army, these traits – discipline, endurance, and cooperation – made them extremely valuable soldiers.

Life on the ocean had also inured the Marbleheaders to the need for vigilance, precision, and attention to detail. Fishermen, merchants, and whalers knew well how to handle a craft in a storm or predict the changing tides and weather. Their work often required long voyages and great courage, as well as strong team spirit. Months and years at sea built up strength and reflexes. Their work itself required an innate knowledge of wind, weather, and tides, a sense of timing, and instinctive trust in their fellow crew members. When these same men took up arms and volunteered for Washington’s small army, these traits – discipline, endurance, and cooperation – made them extremely valuable soldiers.

The Marblehead Regiment was formed under the leadership of wealthy merchant and shipowner John Glover, a patriotic man who inspired his fellow townspeople to organize and prepare. Glover, who had commanded both fishing vessels and merchant ships, was well known in the town for his probity and ability to lead others. When the colonists’ differences with the British government reached a point of no return, Glover was among the first to support the cause of independence and worked to mobilize Marblehead’s town resources for the struggle.

Led by Glover, the Marblehead men formed what was then known as the Marblehead Regiment, officially the 14th Continental Regiment —an amphibious fighting force whose experience and skills were unlike any other fighting force in the Revolution. Able to move between sea and land with practiced ease, these mariners from Marblehead would later be used for several crucial assignments where their seamanship would prove critical.

Notably, the Glover regiment was one of the most ethnically diverse in the Continental Army. Free Black men, Native Americans, and immigrants served alongside white colonists from the Marblehead area—an unusual mix for the 18th century. The men had spent years working together on the decks of Marblehead’s fishing boats and transport ships; in such a setting, they knew one another not by social class but by seamanship and hardiness. In war, this same brotherhood remained. Skill, loyalty, and a common patriotism would continue to unite Glover’s men in battle, and the regiment’s unusual racial and ethnic diversity would not diminish their esprit de corps.

In these mariners from Marblehead, George Washington found one of his great ironies. These were men not just as soldiers, but as seamen, whose skill with wind and tides would be used to repeatedly save his army from disaster. And from the windswept coast, out of the tumbledown cottages of an Atlantic beach town, came the regiment whose courage and skill at cooperation would help guide the American Revolution to victory.

The Birth of a Fighting Regiment

This ability to take to the water came largely from their experience as sailors. Glover’s regiment could operate his boats in any conditions: fog, wind, shifting tides, and icy currents. Their training and discipline under fire quickly impressed Washington and his officers.

They could move in bad weather or near gale-force winds, conditions that caused others to falter. It was a talent honed over years of living and working in one of the harshest stretches of the North Atlantic, where trading and fishing were the primary activities along the coast. Fast and adaptive, working as a single unit, they added flexibility to the Continental Army that it so desperately needed in those early months of the war.

Glover’s regiment was not just a group of able seamen; they were capable fighters as well. They built fortifications, guarded roads and supply lines, and manned the small craft that patrolled Boston Harbor. Always on the alert for British maneuvers, they became a unique hybrid force, both infantrymen and mariners.

The result was a Continental Army with capabilities Washington might never have otherwise imagined.

George Washington came to rely on Glover and his men quickly. He had watched these Marblehead fishermen put into practice their drills with precision and skill, with a fealty to their officers that Washington did not always see. He called the regiment his “naval arm” on more than one occasion, a telling description given the landlocked nature of the war to that point. In a conflict that would be fought primarily on land, his naval arm was his most trusted unit for missions between. And as Glover’s Marblehead Mariners grew in reputation, it would be tested under far more dangerous conditions.

The Siege of Boston proved the worth of the regiment, and their value set the stage for much larger challenges yet to come. The British Army would look for every opportunity to crush the rebellion once the war moved beyond Massachusetts, and Washington knew he could count on Glover’s Marblehead Mariners to do the impossible. Their seamanship, their discipline, their unity would save not just one battle, but an entire revolution.

In December of 1776, the American Revolution was on the brink of failure. Washington’s army had been forced all the way across New Jersey by the British in pursuit, and morale was at an all-time low. The soldiers were hungry, cold, sick, and demoralized, their numbers decimated by desertion and the harsh winter conditions.

Many enlistments would be up by the end of the month, and some had already given up on the cause. In the depths of winter, with his back against the wall, Washington decided to make a last-ditch, desperate attempt to turn the tide. He would once again call on Colonel John Glover and his Marblehead Mariners.

In the late summer of 1776, the infant United States was on the verge of annihilation. The Washington Army had just been routed on Long Island, with British General William Howe’s forces coming “into action in five divisions at once,” routing the Continentals. The army was trapped on Brooklyn Heights, between enemy soldiers and the East River. Its only option was escape, with 9,000 men facing certain death. The entire American Revolution was in jeopardy. It had been a horrible month for the Colonials; one regiment of sailors and fishermen was about to perform a miracle of seamanship to change that.

Glover’s regiment menaced a strong current with long hours of rowing. This was no small task by night with many men in small boats. The sound of men and horses would be noticeable from the British fleet if even one person talked or called out.

George Washington ordered the evacuation under the cloak of darkness. During the night of August 29, 1776, the officers set about evacuating all the soldiers, their horses, and their guns across the East River to Manhattan. It would have to be done without the British navy noticing, and it would have to be done before daylight. To cross the river with thousands of men and horses would take time, with boatloads arriving, unloading, departing, and returning for more. John Glover’s regiment of Marblehead Mariners manned the boats. Their familiarity with the sea was no longer a mercantile asset but the lifeblood of the Continental Army.

It was lucky for the Americans that fog rolled in at dawn, just as the last of Glover’s boats were returning from the river. Washington himself had watched Glover’s men from the shore and was one of the last to leave Brooklyn Heights on the other side of the East River.

The men of the Marblehead Regiment of Glover’s Brigade had built their livelihood on the sea. They had spent their entire lives on it, or at least on the shores of Massachusetts and Maine. Navigating the dangerous, rocky coastline had made them all into sailors and fishermen. Their skill at seamanship was a requirement of business. Now it was going to be the salvation of the American Revolution.

Glover’s regiment menaced a strong current with long hours of rowing, no small task by night with a lot of men in small boats. The sound of men and horses would be noticeable from the British fleet if even one person talked or called out. Once the evacuation had begun, the American soldiers were at the mercy of the sea. The British fleet was close by; one false move and all would be lost.

At the beginning of the operation, the British Army was almost completely unaware of the evacuation. The Americans were able to make good progress, but they did not know if the British Navy was just asleep or waiting for the fog to lift before beginning their own search for the Continentals.

It is lucky for the Americans that fog rolled in at dawn, just as the last of Glover’s boats were returning from the river. Washington himself had watched Glover’s men from the shore and was one of the last to leave Brooklyn Heights on the other side of the East River. By morning, all of the men, horses, and equipment had crossed the river. Nine thousand men had their guns and all of their supplies. It was nothing short of miraculous.

As it turned out, the evacuation of Long Island in 1776 was one of the largest rescues in American history. For Washington, it was a close call that showed just how easily the war could have been lost. Instead of being captured and his army destroyed, Glover’s Mariners had turned defeat into survival. The fighting was not over, but the Americans had been given a second chance to succeed. The skill and seamanship that defined the men of Marblehead would now save the American Revolution.

Holding the Line: Pell’s Point and White Plains (October 1776)

After the long and fortuitous retreat from Long Island, Washington’s army was in danger again. In early October 1776 British General William Howe made a bold attempt to surround the American army north of Manhattan. To protect the Hudson River from an amphibious landing, Washington had left Colonel John Glover’s brigade to hold Pell’s Point, an advanced position on the mainland. On October 14, 1776, Glover’s orders placed his brigade in the path of the British attack. They were to delay the advance as long as possible, allowing Washington to pull the bulk of the army back to safety.

Four days later, on October 18, Howe’s men made a landing near Pelham Bay. Glover immediately formed his lines upon stone walls and into the woods, using the terrain to his advantage. When Howe’s troops advanced, they were met with fire that bogged them down and slowed their advance. Despite being outnumbered almost five to one, Glover’s men were fast, mobile, and accurate, characteristics that had already become a trademark. By the end of the day, the British attack had stalled, and the Americans had gained an unexpected victory.

The Battle of Pell’s Point was a relatively minor engagement, but it allowed Glover’s men to prove their worth and determination to Washington. The 14th Regiment of Glover’s original Marblehead unit did not see action in the battle, as they were held in reserve.

As Washington’s army continued to retreat north to White Plains, Glover’s brigade kept busy. They raided British supply lines and foraging parties, as well as stealing provisions that the hungry Continental Army so desperately needed. On one such mission, a group of Marbleheaders captured over 200 barrels of pork and flour from Eastchester. A few days later, a Marblehead scouting party ambushed and killed twelve Hessian troops while capturing three prisoners. These quick, efficient strikes would help to keep the enemy on their toes and give Washington’s army more time to make good their escape.

The next significant engagement came at the Battle of White Plains on October 28, 1776. There, the Marbleheaders manned artillery batteries and took to the field in support of the main line of defense. When Washington ordered a retreat, it was the men of Marblehead that helped form a rear guard to cover the American army and allow them to escape in good order. Their calm, coordinated discipline in the face of overwhelming odds prevented another disaster.

By the time the army retreated to New Jersey, Glover’s men had proven themselves again. Through their actions at Pell’s Point and White Plains, the fighting, the raiding, and the covering of the retreat, Glover’s men gave Washington’s army the space and the time to fight another day. Through hard work, coordination, and will, the Marblehead Mariners held the line when it mattered.

The Second Rescue: Crossing the Delaware (December 1776)

In December of 1776, the American Revolution was on the brink of failure. Washington’s army had been forced all the way across New Jersey by the British in pursuit, and morale was at an all-time low. The soldiers were hungry, cold, sick, and demoralized, their numbers decimated by desertion and the harsh winter conditions. Many enlistments would be up by the end of the month, and some had already given up on the cause. In the depths of winter, with his back against the wall, Washington decided to make one last-ditch, desperate attempt to turn the tide. He would once again call on Colonel John Glover and his Marblehead Mariners.

It was a freezing Christmas night on December 25, 1776. Winds howled and a blinding snowstorm lashed at Washington’s men as they prepared to cross the ice-filled Delaware River and attack the Hessian garrison at Trenton. The British were guarding the river carefully, the crossing was treacherous, and success was far from guaranteed. Once the operation was underway, there would be no time for delay or hesitation. A fragile chance of victory depended on the safety and speed of the crossing. Washington entrusted the most dangerous and challenging part of the operation to Glover’s men.

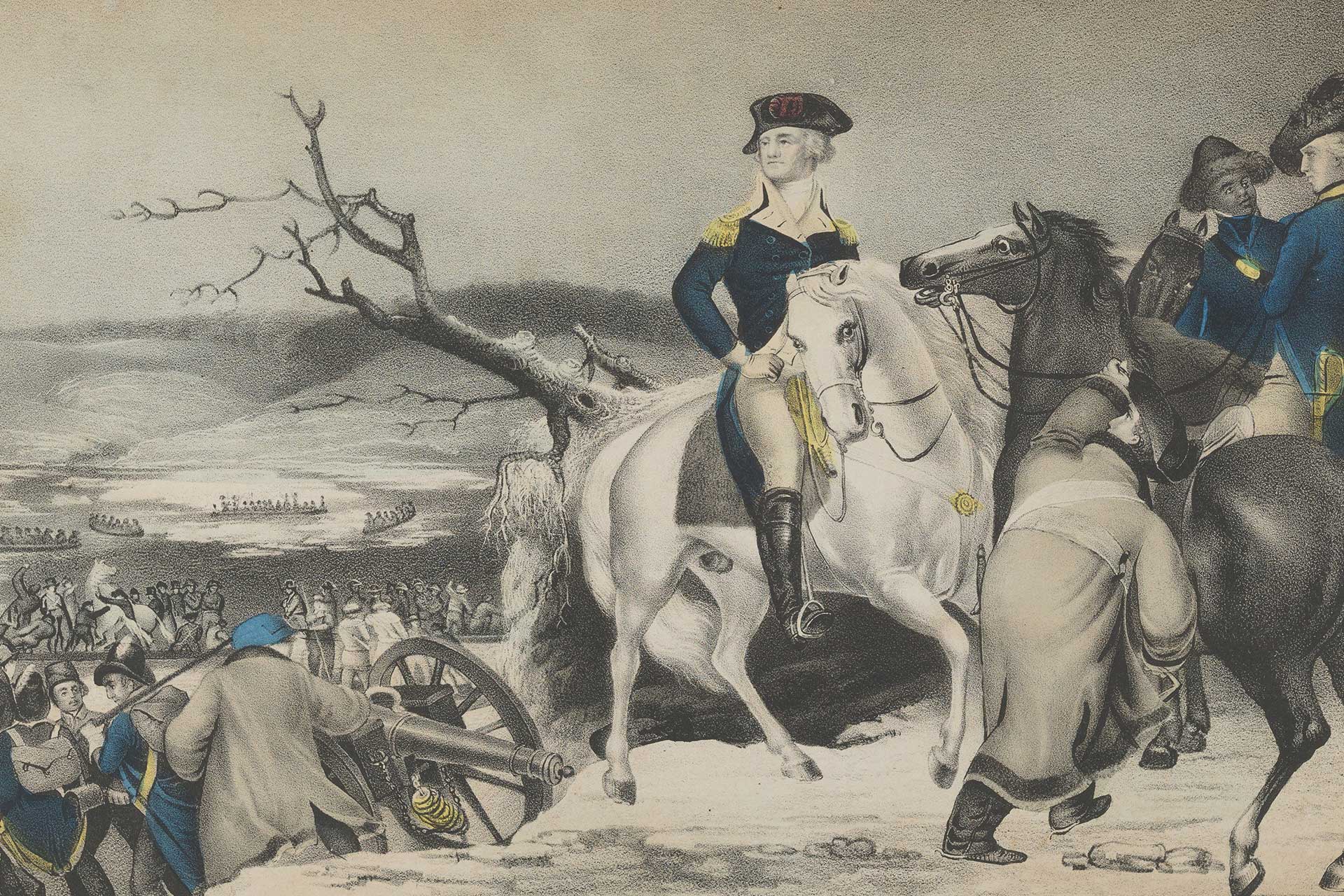

The famous crossing of the Delaware is one of the most enduring images of the American Revolution. It has been commemorated in song and paintings for generations. But it was Glover’s Marbleheaders, steady at the oars in the snowstorm, who stood behind Washington’s back as he made the crossing.

Navigating the icy Delaware in the dark was no easy task, and the job of leading the crossing fell to Glover’s men. The Marblehead Mariners, seasoned veterans of the ocean, were experienced hands at the oars and took charge of the Durham boats. Rowing in silence under the cover of the storm, Glover’s sailors plied the river’s dark waters with military precision. Ice floes clashed and splintered around them, the swirling current swept at their legs, and the freezing wind bit through their clothes. Through the darkness and the chaos, Glover’s men kept quiet and kept rowing, their teamwork a thing of seamanship itself.

The crossing would take nine hours in all. The Marblehead Mariners ferried the army, its artillery, and the horses across the Delaware. Thanks to Glover’s sailors and their unfailing oars, not a single man, cannon, or horse was lost, and Washington himself was on the far shore by the time the army had formed up in order. That morning, the ragtag Continental Army was ready to march on Trenton.

The battle of Trenton was as easy as it was necessary. The Hessians, who had spent the night before drinking and celebrating, were entirely unprepared for the attack. The American victory at Trenton was a significant boost for the colonies. Washington had done the impossible: his ragged, starving army had struck back against the mighty British, and won. It was Glover’s Marblehead Mariners who had made it possible, and who had given the Revolution a second chance…. again.

The famous crossing of the Delaware is one of the most enduring images of the American Revolution, and has been commemorated in song and paintings for generations. But it was Glover’s Marbleheaders, steady at the oars in the snowstorm, who stood behind Washington’s back as he made the crossing. The revolution would have perished without them: Glover and his sailors and their unrivaled seamanship had once again saved the day.

End of Service and Return to the Sea

Despite Washington’s request for six more weeks and promises of bounties for extended service, few men from the Marblehead Regiment chose to reenlist after the victory at Trenton. The brutal winter and constant campaigning had already taken a severe toll on their strength, and many more of these poor fishing and farming men felt they had done their duty and longed for home. The Marblehead Regiment was reorganized on January 1, 1777, under the command of Colonel William R. Lee, with only nine of the original thirty-two officers reenlisting.

Before heading home, however, the Marbleheaders made one last offer of their services to the Continental command. Sensing the danger to the few Continental frigates still in the Delaware River at the time, the Marbleheaders offered to sail these ships upriver to the relative safety of New England’s waters; this request was refused, but it demonstrated the same steadfast dedication to service that had sustained them in so many other perils.

Shortly after this, the majority of the Marblehead Regiment returned home, resuming their lives and livelihoods at sea. A significant number became privateers, utilizing their skills to exact a more direct—and often more profitable—toll on British shipping, while still serving the cause of the Revolution.

Glover himself did not disband from the Continental Army; however, he was promoted to brigadier general after the Battle of Trenton and continued to command troops at the Battle of Princeton and in subsequent operations. He would also be an essential figure in the American victory at Saratoga (1777), one of the war’s decisive turning points, in which he helped halt the advance of British General Burgoyne. Some of his old Marblehead Mariners also fought on into this period, their experience still helping to harden the Continental Army.

Though Glover would not be present at Yorktown (1781), many Marblehead veterans would fight in the war’s final stages, whether in the Continental Navy or in privateer ships that continued to take a heavy toll of British supply ships and naval blockades. In this way, the skill and courage of these men’s service came to affect the course of the war long after their direct rescue of Washington’s army at the start.

Today, the Marblehead Mariners are remembered not only as heroes of their time but as America’s first “Indispensables.” Their discipline, teamwork, and quiet heroism continue to inspire the armed forces and all who value courage born from conviction.

Although they did not continue as a regiment after Trenton, the men of Marblehead did not cease to be patriots; instead, they transitioned from fighting on land to battling on the open sea, their seamanship and valor helping to ensure that the cause of liberty would not be lost.

In this way, from the shores of the Delaware to the vast Atlantic Ocean, the fighting men of Marblehead continued to do their part in the cause of the American Revolution. Though their regiment had been disbanded, their hands had just as surely pulled Washington’s army from its peril, and their ships would play a pivotal role in the ultimate victory. It is for these reasons that both their service as soldiers and their service as seamen continue to be remembered today.

Legacy of the Marblehead Mariners

The legacy of John Glover and his Marblehead Mariners reaches far beyond their wartime rescues. Their daring feats—ferrying Washington’s army through fog, storm, and ice—laid the foundation for America’s future naval and amphibious forces. Long before the nation had a navy, these seafaring soldiers proved that command of the water could mean the difference between defeat and survival. Their courage and seamanship created a model of discipline and versatility that later generations of American sailors and marines would follow.

Marblehead was one of the early American cities to earn the title “The Birthplace of the American Navy.” Many of its men continued to serve aboard Continental ships and privateers, carrying their maritime skill into every corner of the war. The same qualities that saved the army at Long Island and the Delaware—their calm under pressure, teamwork, and mastery of the sea—became a hallmark of America’s naval tradition. Washington himself never forgot their contribution, referring to Glover’s men as “the indispensable ones,” whose efforts had saved not only his army but the Revolution itself.

Historians now recognize Glover’s regiment as one of the most disciplined and capable units of the entire war. Their ability to act with precision and unity under extreme conditions made them stand out in an army often short on training and resources. Washington’s trust in them was absolute—he repeatedly turned to the Marbleheaders for missions that demanded courage, secrecy, and flawless execution. They were, quite literally, the men he could not afford to lose.

More than soldiers, the Marblehead Mariners embodied the spirit of the Revolution itself—ordinary citizens performing extraordinary acts in the name of liberty. They were fishermen and traders who transformed their daily craft into instruments of war, proving that determination and skill could match any professional army. Their story reminds us that the fight for independence was not only waged by generals and statesmen, but also by men of the sea, whose steady hands carried a nation to freedom.

Today, the Marblehead Mariners are remembered not only as heroes of their time but as America’s first “Indispensables.” Their discipline, teamwork, and quiet heroism continue to inspire the armed forces and all who value courage born from conviction. In saving Washington’s army, they did more than preserve a revolution—they set the course for a nation built on resilience, unity, and the will to endure against impossible odds.

![[Video] Women of the American Revolution](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-29-at-3.53.33 PM.png)

![[Video] Women of the American Revolution Part 2](https://historychronicler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-12-at-2.54.41 PM.jpg)